Written and photographed by Robert Gregson

Written and photographed by Robert Gregson

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Winter 2009-2010

SUBSCRIBE/Buy the Issue

When we think of the word “Modernism,” 20th-century design probably comes to mind. As a movement, however, Modernism began in the late 19th century in both Europe and America during the rise of the machine age. It became a creed as much as a style– rejecting the forms of the past in favor of an architecture that reflected a new way of living. After World War II thousands of veterans returned home. With a growing economy, need for affordable housing, and a desire for a stable and fulfilling life, America was poised for change. In Connecticut, a concentration of architectural pioneers settled in rural areas close to the Manhattan hub. They built homes for themselves and friends that incorporated new materials and construction techniques developed during the war. Fifty years later, we call this pivotal legacy “Mid-century Modern.”

These few buildings represent the hundreds of important Modernist buildings located throughout Connecticut.

Modernism Comes to Connecticut

Modernism Comes to Connecticut

Probably the first Modernist building in Connecticut is the Frederick Vanderbilt Field House (1930-31) in New Hartford designed by William Lescaze. Reflecting the European International Style of “form follows function,” the Field House incorporated many Modernist idioms of the time including a flat roof, pipe-railing balcony, concrete construction, and ribbon window.

In Hartford, A. Everett Austin, Jr. (1900-1957), the precocious director of the Wadsworth Atheneum, promoted Modernism in all forms – painting, sculpture, theater, and dance. In 1934 he commissioned (and helped design) the first International Style museum interior in America – the Avery Memorial – which became a showcase for exhibitions by Pablo Picasso, Salvador Dali, and others and for an opera by Gertrude Stein. The sleek interior has cantilevered balconies around a sky-lit atrium. Austin’s office was furnished with classically modern tubular furniture by Marcel Breuer and Le Corbusier.

These projects set the stage, but it was not until after World War II, with the construction of the Interstate Highway System and the ensuing corporate boom, that Connecticut Modernism took off.

New Canaan and the Harvard Five

New Canaan and the Harvard Five

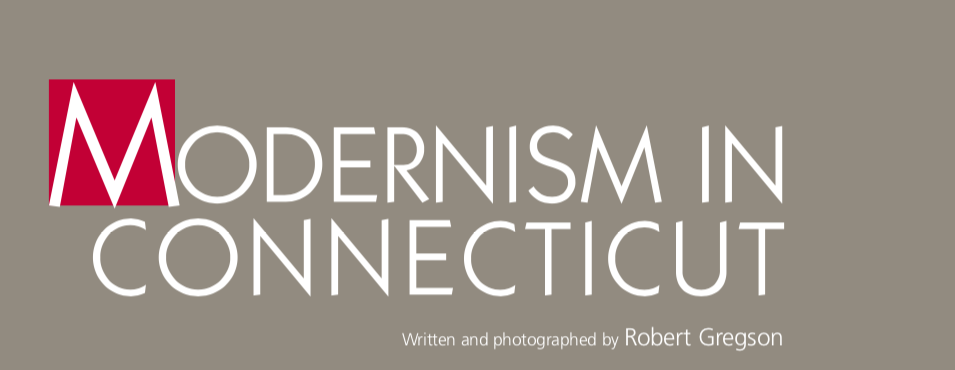

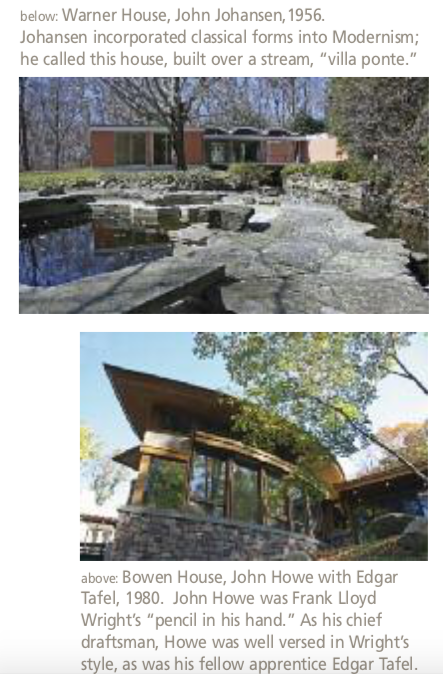

Along with Walter Gropius and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Marcel Breuer (1902-81) was one of the most important Bauhaus architects to settle in the United State in the 1930s. Working with Gropius, he taught at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design from 1937 to 1946 and influenced a generation of American architects. He settled in New Canaan in 1948, along with several other colleagues from Harvard – Philip Johnson, Eliot Noyes, John Johansen, and Landis Gores – who were collectively nicknamed the Harvard Five. As a rural suburb outside New York, New Canaan became a laboratory for architectural invention. Along with a second wave of architects, the Harvard Five were drawn to what others considered unbuildable lots with rugged outcroppings of stone and steep hillsides that added drama to their designs. In 2008, the National Trust for Historic Preservation, New Canaan Historical Society, Philip Johnson Glass House Museum, the Connecticut Trust for Historic Preservation, and the Connecticut Commission on Culture & Tourism formed a partnership to fund a study on these buildings.

New Haven as a Model City

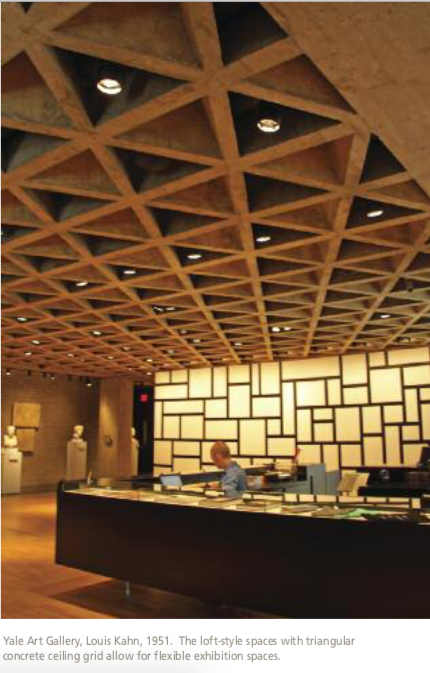

One of America’s earliest city plans was created in 1638 with New Haven’s “nine-square grid.” The framework remains today, allowing subsequent generations to leave their mark on New Haven while retaining its history. No one was more ambitious than Mayor Richard C. Lee (1916-2003), who launched urban renewal programs in the 1950s and ‘60s. Vast federal and state funds made it possible to for New Haven to build highways, schools, housing, and industrial buildings. With Yale University’s participation, a number of architecturally significant buildings resulted. Internationally known architects including Louis Kahn, Paul Rudolph, Marcel Breuer, John Johansen, Philip Johnson, Edward Larrabee Barnes, and Eero Saarinen contributed to the transformation of New Haven as a vital Modernist city.

The Legacy of Litchfield

Litchfield is a quintessential colonial town in northwest Connecticut. But in the 1950s and ‘60s, the seeds of Yankee innovation were at the heart of community leaders Andrew Gagarin and Rufus Stillman. Between them they engaged Marcel Breuer to design five residences, the Torin Corporation in Torrington (Breuer also did the headquarters for SNET), and secured him for four schools. Through their influence, Litchfield also boasted educational facilities, libraries, and homes by other notable architects including Eliot Noyes, Edward Larrabee Barnes, John Johansen, and Richard Neutra. Marcel Breuer designed a large “modern villa” for Andrew Gagarin, while Rufus Stillman commissioned a series of three separate houses (plus a version of Breuer’s Wellfleet cottage) over the course of 20 years.

Gagarin House 1, 1955, Marcel Breuer The Gagarin House features Breuer’s signature staircase and his sculptural bush-hammered fireplace

Modernism Takes Root

As Connecticut flourished economically it became a fertile ground for Modern architecture. In Bloomfield, for example, the Connecticut General Insurance Company built the first corporate campus in America. Designed by Gordon Bunshaft (1909-90) of Skidmore, Owings and Merrill, the interiors were planned by the legendary designer Florence Knoll with gardens and sculpture by artist Isamu Noguchi. Hartford’s elliptical Phoenix Mutual Life Building was designed in 1963 by the firm of Harrison and Abramovitz, while in Stamford, Wallace K. Harrison (1895-1981) designed the First Presbyterian Church in the shape of an abstract fish with stained glass embedded in the concrete walls. In Suffield, Warren Platner (1919-2006) designed a library with ramps that surround a glass-walled garden courtyard.

Connecticut continues to be home to many of world’s foremost architects including AIA Gold-Medal Award winners Cesar Pelli (designer of the Petronas Twin Towers – once the world’s tallest buildings) and Kevin Roche (the 1982 Pritzker Architecture Prize winner). Modernism as a movement is still exploring new directions, and Connecticut still plays a critical role largely due to the Yale School of Architecture, which attracts the world’s most innovative architects.

Also featured in the article:

Avery Memorial, Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford, 1934

Architects: Morris and O’Connor

The art-deco decoration of the exterior belies the austere modern interior treatment.

The Glass House, 1949

Architect: Philip Johnson

Originally influenced by Mies van der Rohe, Johnson liked to create a “procession” of spaces through his designs.

T he Gores House, 1948

he Gores House, 1948

Architect: Landis Gores

Gores liked his architecture to hug the ground. In his own home horizontal roof planes are suspended at various levels, constantly changing the spatial experiences of the interior and exterior spaces.

Yale School of Architecture (Rudolph Hall), 1963

Architect: Paul Rudolph

Textured concrete walls form a complex of intricate spaces.

Ingalls Rink, 1953

Architect: Eero Saarinen

The roof is suspended from a sweeping arch spanning the rink.

Oliver Wolcott Library, 1965

Architect: Eliot Noyes

White-painted bricks pay homage to Colonial architecture in this understated addition to the Oliver Wolcott House.

Wilde Building, Bloomfield, 1957

Architect: Gordon Bunshaft, Skidmore, Owings and Merrill

Hailed as the first corporate campus in America, the Wilde Building provided employees with a bucolic work setting and efficient office space.

First Presbyterian Church, Stamford, 1958

Architect: Wallace K. Harrison

Constructed of pre-cast concrete slabs, this church was meant to recall the great cathedrals of Europe in a Modern form.

Phoenix Insurance Building, Hartford, 1963

Architects: Harrison & Abramovitz

The world’s first two-sided building, this was originally conceived to serve as a visual landmark from the highway. The building is listed on the National Register for Historic Places.

Kent Memorial Library, Suffield, 1972

Architect: Warren Platner

Platner designed his buildings from the inside out. Peaceful spaces look into the tranquil glass-enclosed garden.

First Unitarian Congregational Society, Hartford, 1962

Architect: Victor Lundy

The central roof is supported by cables suspended from concrete radial walls of different heights, angles, and distances from one another. The concept was to create a metaphor of diversity finding a common ground in the unifying space of the sanctuary with a tent-like wooden ceiling that evokes the rays of the sun.

Read More!

Architect Kevin Roche, Shaping Environments, Summer 2022

The Intense Light of Stamford’s First Presbyterian Church,” Spring 2022

Eliot Noyes, Design Pioneer, Spring 2020

The Head & Heart of Architect King-lui Wu, Spring 2020

Philip Johnson’s 50-Year Experiment in Architecture & Landscape, Winter 2019-2020

Philip Johnson in His Own Words, Winter 2009-2010

Discovering Lagardo Tackett, Winter 2011/2012

Connecticut’s Frank Lloyd Wright-Designed “Running Waters,” Spring 2018

Grating the Nutmeg Podcast: Mad for Mid-Century Modern in Connecticut

with Bob Gregson and Peter Swanson

The Answer is Risom! Winter 2009-2010

Lustron: Metal Homes for the Atomic Age, Winter 2009/2010

Yale’s Ingall’s Rink, Fall 2009

Louis Kahn Buildings at Yale, Winter 2006/2007

When Artists Owned Hartford’s Streets, Winter 2004-2005

The Award-Winning Wilde Building, Winter 2003

The Wilde-Building: A Building for the Completely Insured Air Age, Winter 2003

Gores Pavilion for the Arts, Irwin Park, New Canaan, Spring 2013