(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Spring 2020

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

You might be familiar with the work of Eliot Noyes and not realize it. If you have ever used an IBM Selectric typewriter or stopped for gas at a Mobil station, you have encountered his work. From his home base in New Canaan, he was pioneering in a new way of thinking about design and the impact on business. Yet he would insist, “I am first an architect.” As his son Fred Noyes told me in a recent interview, he used the techniques of architectural thinking to expand the boundaries of his design approach. Eliot Noyes might be considered an early holistic thinker who could visualize projects from many vantage points. Throughout his life, he experienced professional coincidences and was uniquely prepared to meet the oncoming challenges of an evolving design world. Eliot Noyes was a person of many talents and interests that seamlessly fit together.

The Formative Years

As Gordon Bruce relates in Eliot Noyes (Phaidon Press, 2006), Noyes was born in Boston, Massachusetts in 1910. He was the second child of Atherton Noyes and Margaret Davenport Fette. After his father contracted tuberculosis, the family moved to Colorado Springs. There his father took a position as a professor of English and Greek at Colorado College. In 1917 the family returned to Massachusetts, where his father taught English literature and writing at Radcliffe College and Harvard University. Eliot attended Phillips Academy in Andover, and after graduation he traveled to Europe. Architecture became a central theme of the trip, and he found himself in awe of the cathedrals he saw.

On his return in 1928, Noyes entered Harvard to study English, Greek, and Latin. He worked on the Harvard Lampoon, where he used his drawing skills as an illustrator. He honed his artistic abilities at a small art school in Ogunquit, Maine in 1929, just as the Great Depression hit and money became very tight. Despite the family’s modest financial means, Noyes enrolled in the Ecole Americaine des Beaux-Arts outside Paris in 1931. After more travel, he returned home to the realization that he wanted to be an architect.

Harvard School of Design

Noyes entered Harvard’s Graduate School of Design in 1932. The basic foundation of architecture schools at the time was the Beaux-Arts method. He continued to sharpen his technical abilities in drawing and watercolor by creating beautifully rendered illustrations of classical architecture. As Fred Noyes noted, despite this talent, this work became drudgery, and by focusing on the past, Eliot did not learn about modern-day solutions. Architects such as Frank Lloyd Wright, Le Corbusier, Mies van der Rohe, and Walter Gropius were being published, and their work captured his imagination. Noyes considered attending the Bauhaus but was deterred by the Nazis’ violence and the political upheaval in Germany. Fortunately, in 1937, the Bauhaus came to him when Gropius was named chairman of Harvard’s Graduate School of Design. Gropius had far-reaching connections to the most innovative people in the world, including the architect Marcel Breuer. Noyes became a member of Gropius’s first class in America. Gropius changed Noyes’s life.

At Harvard Noyes became connected with other brilliant students such as Philip Johnson and John Johansen. In 1940 Noyes was in a unique position when Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) founder Alfred H. Barr and architect Wallace K. Harrison were looking for a “fearless” director of industrial design for a new department and asked Gropius for his recommendation. According to Bruce in Eliot Noyes, Gropius’s answer was Eliot Noyes.

MoMA, as perhaps the ultimate authority on modern design, provided the ideal testing ground to introduce new design solutions to the public. It also provided a place for Noyes to develop his facility as a creative catalyst by bringing talented artists and designers together. MoMA became a showcase for Noyes’s vast knowledge, gleaned from his world travels and skills as a designer. Now he could champion well-designed objects and their availability in the mass market. Exhibitions such as Useful Objects of American Design Under $10 in 1940 educated the consumer and promoted the idea that good design could be available for everyone.

MoMA, as perhaps the ultimate authority on modern design, provided the ideal testing ground to introduce new design solutions to the public. It also provided a place for Noyes to develop his facility as a creative catalyst by bringing talented artists and designers together. MoMA became a showcase for Noyes’s vast knowledge, gleaned from his world travels and skills as a designer. Now he could champion well-designed objects and their availability in the mass market. Exhibitions such as Useful Objects of American Design Under $10 in 1940 educated the consumer and promoted the idea that good design could be available for everyone.

In 1947 Noyes was eager to put his design theories into practice and decided to leave MoMA. The museum had nurtured his ideas about industrial design, but his first love was architecture. His first project was a home for his family, for which he was both architect and client. He settled on a lot in New Canaan, Connecticut, which was then a small rural town with few zoning restrictions—providing him freedom in planning and design.

Noyes needed an income to support his wife Molly and his growing family of four children. He took a position with Norman Bel Geddes, a visionary architect and designer from a previous generation. Bel Geddes’s work was very theatrical, showy, and slightly outdated—everything Noyes was not. Bel Geddes was one of the forerunners of 20th-century industrial design. He designed trains, automobiles, ships, appliances, and airplanes, all packaged in sleek, streamlined forms. It was about this time that Bel Geddes was approached by IBM to redesign the company’s new Selectric typewriter.

The Industrial Designer

In the early 1950s IBM was led by Chairman of the Board Thomas Watson Sr. His son Thomas Watson Jr. joined the company in 1937, became president in 1952, and became chairman of the board in 1961. Noyes had met the younger Watson during World War II. Watson was a pilot, and Noyes was a glider pilot. They were introduced in the halls of the Pentagon. At a meeting at the Bel Geddes office, Watson recognized Noyes and was surprised to find out that he was a designer. Bel Geddes put Noyes in charge of the Selectric typewriter project.

To begin the design process Noyes visited the IBM headquarters in New York City to assess how IBM conducted business. What he found was an array of awkwardly designed business machines, including typewriters, tabulators, and relay calculators. There was a sorter with cast-iron Queen Anne-style legs. The offices were a collection of mismatched building styles and graphics. Watson Sr. had coined the slogan “Think,” which appeared on office walls throughout the building.

When Bel Geddes decided to close his financially ailing office in the late 1940s, Watson asked Noyes to finish the project. This became the roots of Eliot Noyes & Associates and Noyes’s next professional evolution.

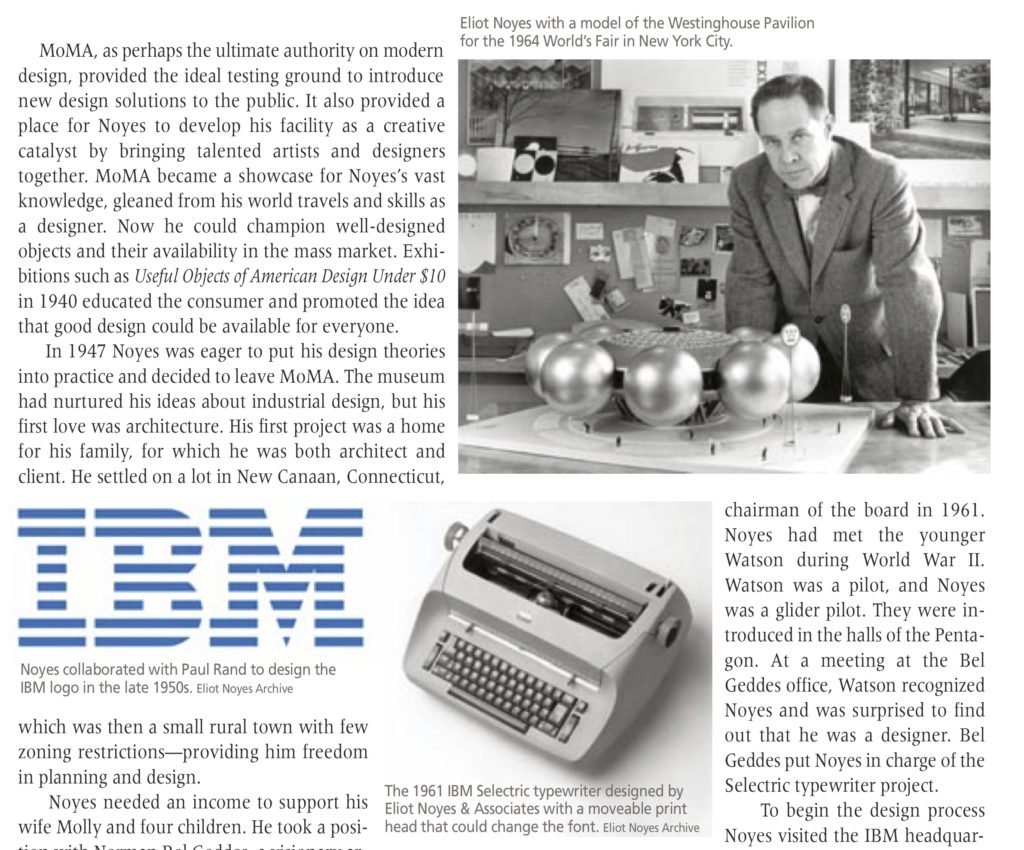

Noyes designed the sculpted shell of the Selectric typewriter, but there was a problem with the typing mechanism that created the letter impressions. In The Look of the Century (Dorling Kindersley Publishers Ltd, 1996), Michael Tambini noted the ingenious solution created by Noyes employee Allan McCroskery of a “golfball” type head to replace the type bar. It was revolutionary. The interchangeable heads made for a greater choice of typefaces. The final design of the typewriter was a hit and made millions of dollars for IBM.

With the success of the Selectric, Noyes proposed an ambitious design program that would affect every element of IBM’s image. He engaged a team of designers—the best people he knew and trusted—to guide the process. Although graphic designer Paul Rand had never done a complete corporate graphic system before, Noyes knew his work and had faith in him. Rand created the new logo, as Steven Heller relates in Paul Rand (Phaidon Press, 2000). Not surprisingly, there was some push-back from entrenched managers, but Noyes prevailed. In addition to the new trademark, Noyes developed a program of how, where, and when to use the new logo, always reinforcing the brand in all marketing efforts. Ray Eames and Charles Eames were hired to make films that humanized computers and other new technologies. Noyes felt that the reflection of a company’s best attributes became its design identity.

With the success of the Selectric, Noyes proposed an ambitious design program that would affect every element of IBM’s image. He engaged a team of designers—the best people he knew and trusted—to guide the process. Although graphic designer Paul Rand had never done a complete corporate graphic system before, Noyes knew his work and had faith in him. Rand created the new logo, as Steven Heller relates in Paul Rand (Phaidon Press, 2000). Not surprisingly, there was some push-back from entrenched managers, but Noyes prevailed. In addition to the new trademark, Noyes developed a program of how, where, and when to use the new logo, always reinforcing the brand in all marketing efforts. Ray Eames and Charles Eames were hired to make films that humanized computers and other new technologies. Noyes felt that the reflection of a company’s best attributes became its design identity.

In 1956 Noyes was appointed design director for IBM. He had an unusual arrangement in which he would spend part of his time working for IBM and the other part as an independent designer with his own staff.

In 1960 Westinghouse hired Noyes to create a better design program for the company. Noyes met with Westinghouse leaders in Manhattan. It became clear to Noyes that Westinghouse needed a different approach than the one he’d taken with IBM. Westinghouse did not have an easily definable product. What did Westinghouse do? Noyes’s challenge was to take complicated business segments such as atomic submarines, molecular electronic developments, thermoelectricity, power generation, and ultrasonics and give them a visual expression.

Noyes put together his creative team. Again, he tapped Rand to develop a graphics program and trademark. Ray and Charles Eames designed corporate trade shows and made films to illustrate and bring to life Westinghouse’s vast spectrum of products. Westinghouse also hired Eliot Noyes & Associates to develop a rapid-transit vehicle for Pittsburgh that involved collaborating with a team of architects, urban planners, and industrial designers. Noyes made sure that every detail reflected the personality of Westinghouse.

The success of Noyes’s approach began to gain traction, and his expertise was in demand. His next project came from Rawleigh Warner Jr., the president of Mobil Oil. Warner lived not far from Noyes in New Canaan. He shared Noyes’s interest in modern design and lived in a house designed by Noyes’s friend from Harvard, John Johansen.

Warner was familiar with Noyes’s work for IBM and Westinghouse and contacted him to create a program for Mobil. Noyes explained to Warner, as Bruce notes, that design is not a superficial beauty treatment but a whole process that connects objects, systems, and environments to people. By 1965 Noyes Associates transformed the Mobil identity, giving it a clean, modern look. Rand, overwhelmed with other projects, declined to participate, so Noyes engaged the firm of Chermayeff & Geismar to design the graphic treatment (including the red “O” in the Mobil trademark). Eliot Noyes & Associates focused on the overall concept and the architecture and design for gas stations—including a cylindrical gas pump. From gas stations to logo and signage, Mobil now stood out in the landscape. According to Elizabeth Mills Brown in New Haven: A Guide to Architecture and Urban Design (Yale University Press, 1976), the first of the newly designed stations was located in New Haven, just off Route 15. More than 50 years later, Noyes & Associate’s design work is still in use as the global face of Mobil.

In 1965 Eliot Noyes designed Mobil’s new look for its gas stations, including oversight of a new logo, the cylindrical pump, and other elements, seen here in the first station using the Noyes design in New Haven.

The Architect

Despite his great success with corporate clients, Noyes’s first love continued to be architecture. The same talents he used in facilitating corporate projects were focused on the design of how we live. As his son Fred Noyes said, “Design permeated everything. It was a way of life.” The second New Canaan home he built for his family in 1955, is an example of how this was applied. The house was conceived to accommodate four children and an assortment of pets, including a rabbit, squirrel, parakeet, doves, and two French poodles. Built in a pine grove, the house is sandwiched between two massive stonewalls, with walls of glass on either end. The house functions as a place to live, eat, and sleep, and also as a place to thrive, grow, and have fun.

As Christian Bjone described it in First House (Wiley-Academy, 2002), the house is divided into two living areas on either side of an open courtyard. One side functions as the private area with bedrooms, bathrooms, and work areas, while the other side is a communal, multifunction public area including the kitchen, dining, living areas, with a generous fireplace. The two sides are connected by a covered outdoor walkway.

As Christian Bjone described it in First House (Wiley-Academy, 2002), the house is divided into two living areas on either side of an open courtyard. One side functions as the private area with bedrooms, bathrooms, and work areas, while the other side is a communal, multifunction public area including the kitchen, dining, living areas, with a generous fireplace. The two sides are connected by a covered outdoor walkway.

Fred Noyes said that the family was never daunted by the need to cross the open courtyard, even in the cold of winter. Noyes invited the seasonal changes as part of the house. The house won many awards, including the AIA Award for Merit in 1957. It was published in Time and Life magazines, with photos of the family playing instruments, reading, and generally enjoying the house.

The house was filled with art, sculpture, folk art, and music. Artists, designers, and friends visited the house constantly, Fred notes. Artist Alexander Calder was a close friend [See “Calder in the Open Air,” Spring 2015.]. His mobiles hung in front of the glass walls on either side of the main living area. When Noyes suggested a sculpture for the courtyard, Calder arrived with several small maquettes. Fred described how a slide projector was used to spotlight and enlarge shadows of the models on the wall to determine which model worked the best in the courtyard. The final work was Calder’s first stabile (non-moving sculpture). Calder was concerned about the flexibility of the sheet metal. To reinforce the sculpture, Noyes suggested gussets as ribs to stiffen the plane. It was so successful that Calder used the idea on other large-scale sculptures for the rest of his life.

One of Noyes’s favorite houses was one he designed for the Ault family in New Canaan. In a 1958 article in Art in America he said, “As an architectural problem this was about as interesting and rewarding an assignment as I ever hoped for!” His clients were art collectors and an artist, and their requirements for the house posed special challenges. Like Noyes’s own home, the Ault House combines indoor and outdoor spaces that balance privacy with openness. Along with his corporate projects, Noyes found time to design homes, corporate offices, libraries, and exhibition pavilions.

The Legacy

I appreciate that Eliot Noyes understood how living, working, and playing exist together as one. He found common ground within diverse elements. He was able to orchestrate people, talents, and ideas into a unified whole. He intuitively translated the process of architecture in a new way. His design solutions grew from within the challenges. He was a visionary who pioneered an approach to design that embraced the big picture in both his work and life.

Noyes’s premature death in July 1977 shocked friends and colleagues. Seven weeks after he died, a memorial was held at his home in New Canaan. Filled with friends, colleagues, artists, and designers, it was a celebration of his richly lived life. Noyes was just shy of his 67th birthday.

Robert Gregson is an artist and former creative director of the Connecticut Commission on Culture & Tourism. He last wrote “Josef & Anni Albers in Connecticut,” Winter 2018-2019.

Read More!

The Head & the Heart of Architect King-lui Wu, Spring 2020

Discovering Lagardo Tackett, Winter 2011/2012

Connecticut’s Wright-Designed “Running Waters,” Spring 2018

Philip Johnson’s 50-Year Experiment in Architecture & Landscape, Winter 2019-2020

Philip Johnson in His Own Words, Winter 2009-2010

Gores Pavilion, New Canaan, Spring 2013

Grating the Nutmeg Podcast: Mad for Mid-Century Modern in Connecticut

with Bob Gregson and Peter Swanson

Modernism in Connecticut, Winter 2009-2010