by F. Peter Swanson, M.D.

(c) Connecticut Explored inc. WINTER 2010/11

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

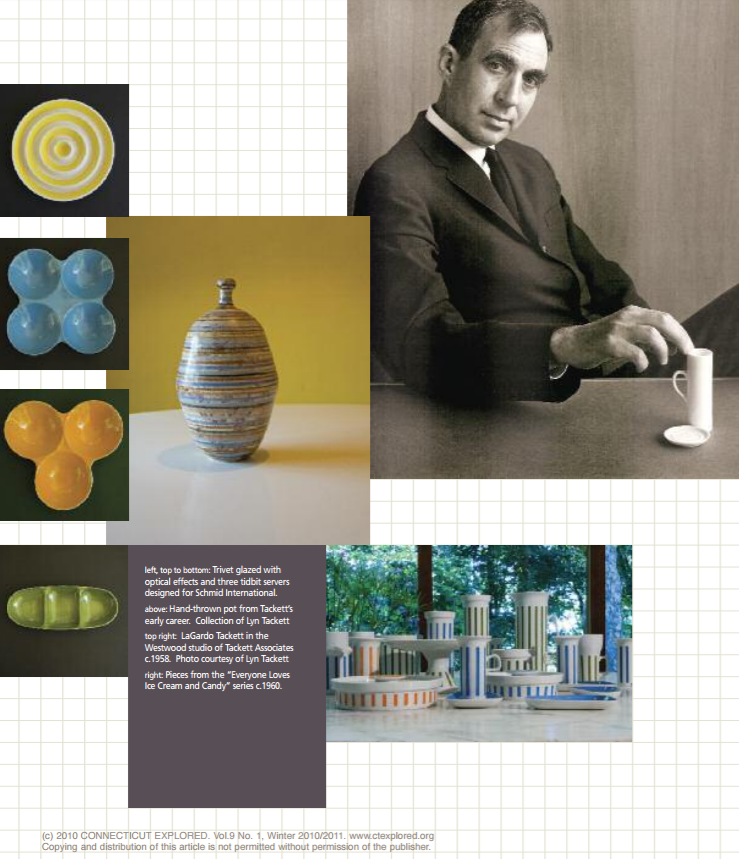

I first heard the name “LaGardo Tackett” in 1984 while looking for real estate. A realtor showed me a duplex row house on a quiet street in the Wooster Square section of New Haven whose simplified exterior distinguished it from its more Victorian neighbors. It was obvious upon entering that this was a unique home. It was furnished with iconic modernist furniture including George Nelson coconut lounges, Eames chairs, and a prototypical Saarinen-like pedestal table with a flush-mounted lazy Susan in its top. Lying beside the Nelson platform bed was a first edition of architect Robert Venturi’s Learning from Las Vegas, as if the reader would soon return. Throughout the house, and densely stacked on metal racks in the basement, were scores of wonderfully simple cylindrical porcelain vessels.

I first heard the name “LaGardo Tackett” in 1984 while looking for real estate. A realtor showed me a duplex row house on a quiet street in the Wooster Square section of New Haven whose simplified exterior distinguished it from its more Victorian neighbors. It was obvious upon entering that this was a unique home. It was furnished with iconic modernist furniture including George Nelson coconut lounges, Eames chairs, and a prototypical Saarinen-like pedestal table with a flush-mounted lazy Susan in its top. Lying beside the Nelson platform bed was a first edition of architect Robert Venturi’s Learning from Las Vegas, as if the reader would soon return. Throughout the house, and densely stacked on metal racks in the basement, were scores of wonderfully simple cylindrical porcelain vessels.

The realtor explained that this was the home of the late LaGardo Tackett. All the ceramics were of his design, and the whole environment was the flawless creation of an accomplished modernist. My sense of awe from every deliberate detail in the apartment was matched only by the sense of loss of never knowing their creator in life. Although I regret not buying the house, I have collected more than a hundred examples of his work since that time. No catalogue of Tackett’s entire body of work exists. While many of his pots are easily recognized, new shapes and uses continue to surface in the “collectibles” marketplace. I hope to shed light on his life’s work here.

Before the Kiln

Tack was born in Henderson, Kentucky on the banks of the Ohio River in 1911 to Oscar, a grocer, and Lillian Tackett. He would later explain that his unique name was taken from the label of a tomato can at his father’s store, and there has never been a more believable account. As a young man he entered Indiana University to study geology. Although he left school after only two years, he met his future wife and life-long collaborator, Virginia Lee Roth of Rensselaer, Indiana, while there. The young couple moved to New York in 1937, married at City Hall, and lived in the Spuyten Duyvil section of the Bronx. Virginia was hired by CUE Magazine, a New York events-listing publication, while Tack worked for the department store giant The May Company. As May was headquartered in Los Angeles, the job generated regular trips to the west coast.

California Bound

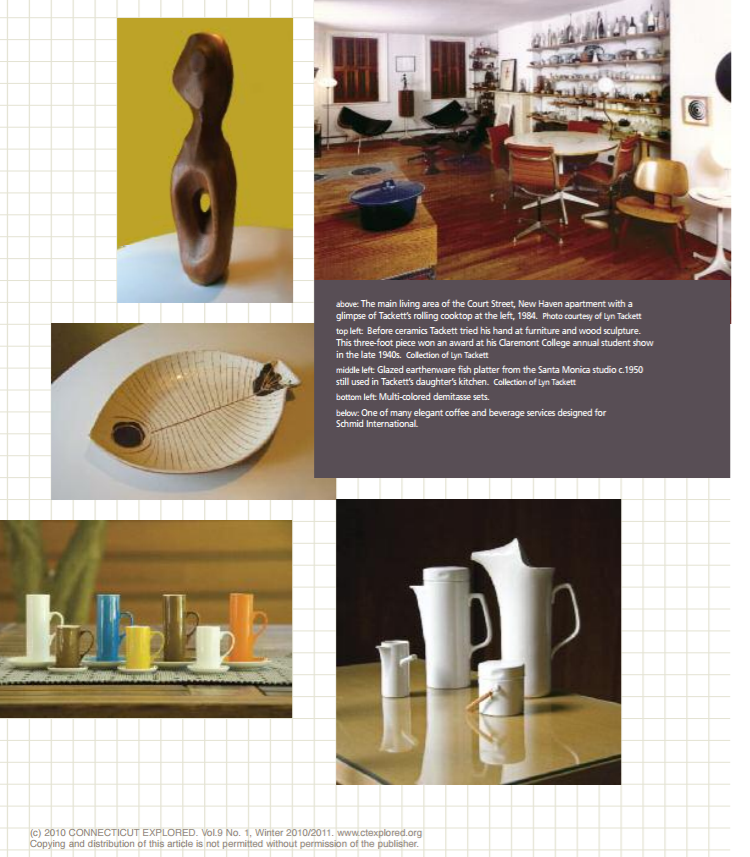

By the early 1940s Tack became May’s interior promotion director, a change that required relocation. Tack and Virginia moved into Baldwin Hills Village within Los Angeles, advertised as “an experimental community for the automotive age.” Just minutes from downtown, it boasted more than 600 garden-style residences on 68 acres of largely green space and remains a coveted address today. Tack attended classes at Claremont Graduate School and began working with ceramics, at first throwing pots and creating free-formed animals. He also experimented with furniture design, and his abstract wood sculpture won an award at the school’s annual student show.

World War II soon placed life and all personal aspirations on hold for the Tacketts, as it did for many American families. Tack was drafted in 1944, the same year the couple’s first child, Sandra Lynne, was born. During the war, Tack suffered several months of fever, pleurisy, and weight loss. Upon discharge in August 1945 he returned home to Virginia and the infant daughter he hardly knew. By 1947 the family grew to include another

child, Cheryl Lee, and Tack used the GI Bill to enroll in Scripps at The Claremont Colleges to study pottery. Scripps offered him a formal academic approach to ceramics, focusing on the techniques of the British potter Bernard Leach, the traditions of the Chinese Sung Dynasty, and classical Greek forms. All left him wanting. He turned his attention to the evolution of cooking and eating utensils throughout history, a topic that interested him for the remainder of his career.

Tack taught at the California School of Art, including one course he called “Three Dimensional Design” at his own kiln in Pasadena. He created many of his signature pieces during this period and began mentoring such students as John Follis and Rex Goode. Their work, along with that of fellow potters Malcolm Leland and David Cressey, was discovered in 1949 at the Evans and Reeves Nursery on Barrington Avenue in West Los Angeles by a pair of New York entrepreneurs, Max and Rita Lawrence. The business-savvy couple marketed the group’s pots under the name “Architectural Pottery,” and the pieces soon became the favorite accents of the California modernist architects for their Case Study houses.

Tack served as president of the design chapter of the Southern California American Ceramics Soc

Tack served as president of the design chapter of the Southern California American Ceramics Soc

iety in 1949-1950, and the Museum of Modern Art showcased Architectural Pottery in its 1951 “Good Design” show organized by Edgar Kaufmann, Jr. and juried by Kaufmann, Philip Johnson, and Eero Saarinen. Many of the Architectural Pottery designs are still produced and sold commercially through Vessel USA, founded in San

Diego.

In 1951 Tackett set up a larger kiln in Topanga Canyon and with the help of an architect in 1952 built a modern house on Big Rock Drive in Malibu— “a white cube with a window to the West,” as he described it in his journal. Further commercial success meant opening an even larger studio in 1953 on 20th Street in Santa Monica, where rails transported rolling racks in to the kiln and Virginia tended to the slip and glazes. The business adopted “Tackett Associates” a sits official name. During long overnight firings Sandra Lynne and Cheryl Lee would sleep in wooden shipping crates filled with packing excelsior. It was still very much a family production.

For a brief time in 1953, Kenji Fujita joined Tackett Associates. Fujita’s work was quite compatible with Tack’s, and he soon became a partner, traveling to Japan to represent the company. Although the relationship dissolved after a year Fujita’s work from the time of the partnership remains well known.

Virginia, LaGardo, and Sandy Lynne (Lyn) Tackett dining al fresco at the Topanga Canyon Studio, c. 1947. Photo courtesy of Lyn Tackett

Tack and Virginia were introduced to Paul Schmid of Schmid International, a large-scale porcelain manufacturer

based in Boston. Their friendship resulted in the Tacketts’ moving in 1956 for two years to Kyoto, Japan, where they lived in a traditional home with shoji screens and tatamimats. Working in near by Nagoya, a center for Japanese pottery, Tack shifted his focus to design and away from hands-on production. The Santa Monica studio was closed. A brief return to Malibu in 1958, during which time Tackett Associates opened a design office in Westwood, was followed in 1960 by another move to Japan, this time to Tokyo.

The Pots

Tack’s earliest foodware designs included a heavy, oven proof, chocolate-brown line known as “Rockingham” that was suitable for preparation, cooking, serving, and storage of food. Terracotta fish shapes were hand-painted on large platters and individual salad plates. But he hit his stride when working with porcelain, for which he held a special respect. One series, distributed by Freeman-Lederman of Van Nuys, featured tapered white decanters for liquor with matching covered containers for lemons, olives, onions, and cherries.

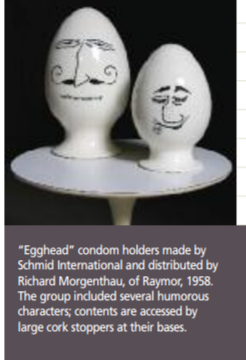

Tack was prolific during the time he designed for Schmid International, and the work she created then are the easiest to find today. Many styles of cylindrical carafes in white porcelain for coffee and espresso were accompanied by delicate, tall, thin cups for espresso and wide-based cups for coffee. Several forms of sugar and creamer pairs complemented the sets. There were flocks of “Sandper” cruets in the form of a stylized bird, as graceful as they were practical. Divided tidbit servers and egg cups were finished in glazes of solid colors.

His daughters recall that at home there was always “a dish for everything” and that they had never seen a bottle of ketchup set on the table until visiting other house holds. Tack enjoyed devising storage containers for condiments, coffee, tea, sugar, flour, spices, oil, vinegar, and pasta. He designed canisters in the form of graduated globes and cylinders with his characteristic red toggle-lid handles. Others were set apart by whimsically scripted labels in the glaze and a bright red dot as found on the Freeman-Lederman spirits sets. W

all-mounted porcelain holders for salt, toothpicks, and pencils were practical additions to the kitchen. A full dining service in pure white with a subtle raised ring on the underside of the rims afforded full attention to the colors of food. Four cookie jars, all variations on a theme, were a mix of man and beast. His anthropomorphic “Black Russian” was a ceramic bottle in the form of a bearded Cossack, created to promote Kahlua. One of his last collections was an ice cream and candy service of white, lidded containers decorated with vertical stripes of festive colors.

Planter designed for Architectural Pottery, 1950, and still in production by Vessel USA

Rarely Tack strayed from ceramics. In 1954, for instance, Schmid sold his “Merry Chris Mobile,” a hanging sculpture made of five glass Christmas balls on a frame of rods and string. He also designed a pair of steel swords stored in a wooden box to be used as skewers.

Tackett in Connecticut

After expanding his ideas for porcelain dinnerware in Tokyo, Tack returned with his family to the United States in 1961, settling in Weston, Connecticut. They rented a locally famous modern home designed in 1954 by George S. Lewis and Allan Gould for Harold Loeb, a friend of Ernest Hemingway and the publisher of the literary magazine The Broom. The house was situated alongside a dam on the Saugatuck River on Buttonball Lane. Tack commuted to New York for meetings at Schmid International. This business arrangement, along with the continued royalties from earlier work, provided continued financial success.

In 1964 Tack and Virginia purchased the George Doubleday mansion called “Westmoreland” on Peaceable Street in Ridgefield and renamed it “Taleria.” They filled the 19th-century house with contemporary furniture from the Herman Miller line, which, along with his ceramics, created a modernist environment within the 19th-century landmark. The house still stands, now serving as the Temple Shearith Israel.

In 1971, with the children grown and on their own, the couple moved to the Milton section of the town of Litchfield, where Tack built a studio next to their 18th-century house. In the summer of 1976 he had a solo art show in Litchfield’s Oliver Wolcott Library, a modern box of white brick and glass designed by Eliot Noyes that was grafted onto the 1799 home of the famous signer of the Constitution. Tack’s exhibition consisted of abstract drawings of primal—often menacing—human figures. During this time he was also very active in arranging programs at the Brookfield Craft Center, founded in 1954 to promote and preserve fine craftsmanship in Connecticut. He would design shows for other artisans’ work and arrange for speakers such as faculty members from The New School in New York.

In the late 1970s, Tack suffered a mild stroke, and Virginia’s increasing confusion would shortly be diagnosed as Alzheimer’s disease. A final move brought them to New Haven, where Tack reasoned they could live and work without a car and still enjoy a culturally rich life while having access to medical care at Yale-New Haven Hospital. They chose the Wooster Square neighborhood on a street of shoulder-to-shoulder row houses from the 1870s. They would be seen walking about town, attending symphony performances and theater at Yale, eating at New Haven’s finest restaurants, and shopping downtown. Tack aimed to slow Virginia’s illness by keeping her as stimulated as possible. He had configured their modest duplex as an open living area on the ground floor, allowing her to keep him in view. The upper floor contained their bedroom and a studio space. A rolling cart of his own design with a built-in cook-top allowed him to prepare food without leaving her sight. Within their apartment he had distilled the decades of design he valued so much, proudly displaying the amazing evolution of his own ceramics on every shelf, credenza, mantel, table, and floor.

Without a kiln or working studio he entered a much more philosophical phase of life. His notebooks are filled with “foodware” essays in which he explored the ever elusive, perfect set of tableware he referred to as “the 5 basic vessels.” He wrote, but apparently never published, other treatises such as Housekeeping Transformed: A New Way of Thinking About Order, Space and Time, which discussed furniture, food, service, and cleaning. He became fascinated by John Gall’s Systemantics, which examined the way complex systems fail. Theories on the nature and role of objects grew into a philosophy of “Situation Design,” originally defined by Edgar Kaufmann, Jr. during a visit to Tack’s studio. As he had done for years, Tack continued to experiment with photography, shooting common objects in uncommon lighting and situations. A narrow backlit walnut box mounted on the wall allowed him to display a long run of 35-mm images. His appetite for design never wavered.

Virginia died in 1982 and Tack in 1984. Their ashes are scattered beneath a spruce planted as a Christmas tree in Virginia’s memory in front of Trinity Church in Milton.

Many thanks to Tackett and Virginia’s daughters Lyn and Lee for sharing their memories and the books, papers, drawings, letters, and photos of their parents. The recollections of the Tacketts’ neighbors from Wooster Square were also invaluable. Unless noted, ceramics are from the collection of the author.

Read More!

The Head & Heart of Architect King-lui Wu, Spring 2020

Connecticut’s Wright-Designed “Running Waters,” Spring 2018

Grating the Nutmeg Podcast: Mad for Mid-Century Modern in Connecticut

with Bob Gregson and Peter Swanson

Modernism in Connecticut, Winter 2009-2010

The Answer is Risom! Winter 2009-2010

When Artists Owned Hartford’s Streets, Winter 2004-2005