(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Fall 2009

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

For structures designed to house athletic events, Yale University’s Ingalls Rink and Yale Bowl have exerted influence beyond the sports arena. Both have reflected and in turn helped define the character of the university and of the city of New Haven.

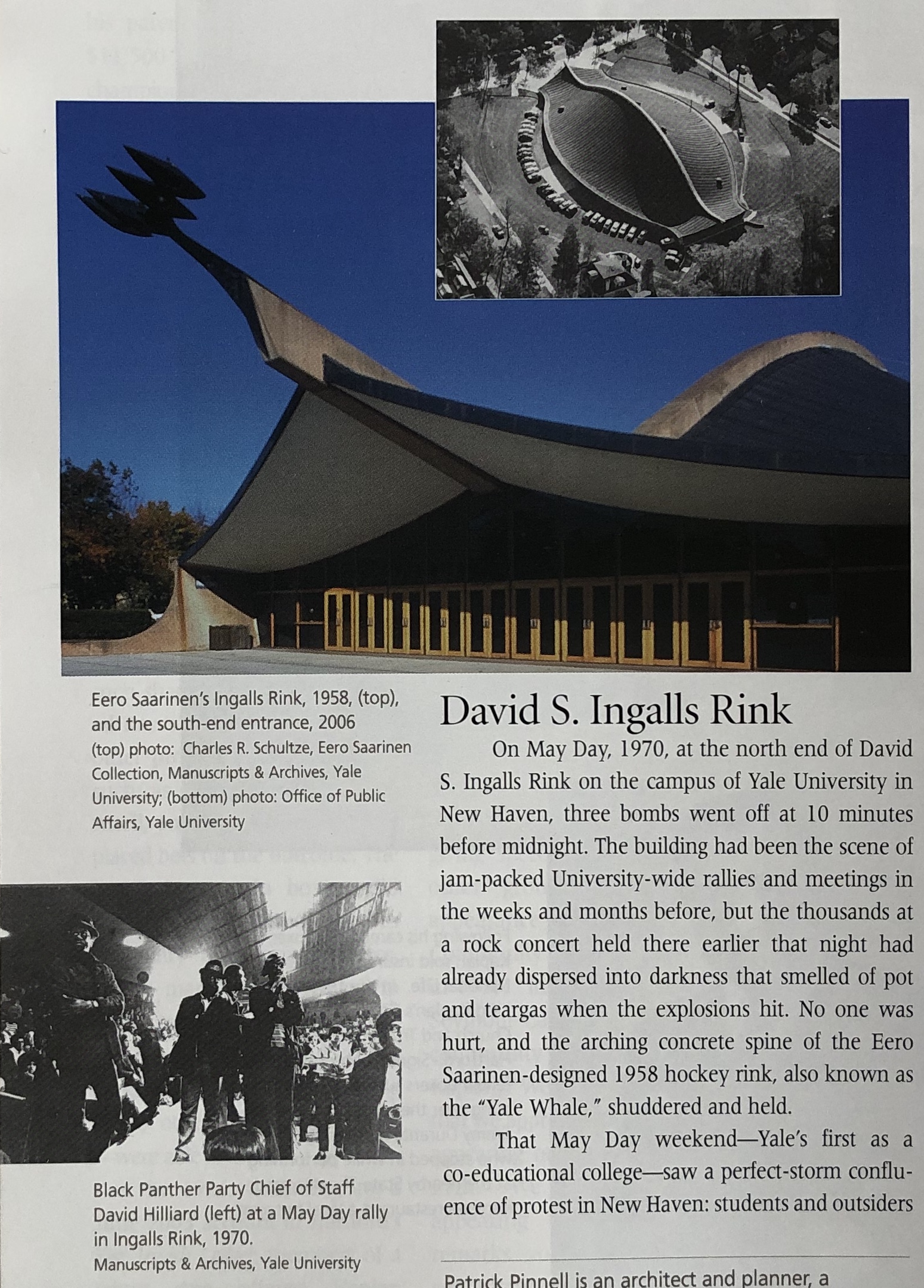

David S. Ingalls Rink

On May Day 1970, at the north end of David S. Ingalls Rink on the campus of Yale University in New Haven, three bombs went off at 10 minutes before midnight. The building had been the scene of jam-packed university-wide rallies and meetings in the weeks and months before, but the thousands at a rock concert held there earlier that night had already dispersed into darkness that smelled of pot and tear gas when the explosions hit. No one was hurt, and the arching concrete spine of the Eero Saarinen-designed 1958 hockey rink, as known as the “Yale Whale,” shuddered and held.

That May Day weekend — Yale’s first as a co-educational college — saw a perfect-storm confluence of protest in New Haven: students and outsiders raised voices and fists against the ongoing Black Panther murder trial [See “The New Haven Black Panther Trials,” Winter 2019-2020.] , the Vietnam War, the elitism allegedly represented by Yale, against the very idea of social control, period. [See “Yale’s Chaplain Takes on the Vietnam War,” Winter 2014-2015.] Friday night’s miracle at the rink went almost unnoticed in the forward rush of everything else. No one was ever identified as responsible for the incident.

Seen from a distance now of almost four decades, Ingalls Rink’s unintended role as public political space in the tumultuous late 1960s and early 1970s is remarkable. No one was thinking much at the time about how this architecture, designed to house and express the speed and force of a sport, gradually became the place of choice for the Yale community to gather to contend its responses to the speed and force of history. Use of the rink as a vessel of debate seems itself in hindsight more than a little surreal, with hot debate replacing ice as the content of the building.

Ingalls Rink served well in helping contain the events of those years. “Contain” describes its role in a double sense: Not only did it provide the setting for mass gatherings, but may have contained the potential for violence and disruption in the university and the city.

Its architect, Eero Saarinen (1910-1961), did not live to see Ingalls turned to political use a decade after its 1958 completion. He would have been pleased at the ease and effectiveness with which it worked. Designed without windows to keep spectators focused on the game, the intense inwardness of the interior space focused rallies as well. Wooden ceiling boards, chosen for their ability to bend along the complex curves of the roof cables hung from the central concrete spine, turned out to be great for acoustics, spreading speakers’ voices and the roar of responding crowds. Unintended too, but fateful was Saarinen’s decision to have everyone enter and leave the building via doors on the south end, in the direction of the central Yale campus — and away from the May Day bombs planted near the north-end service entry.

As a 1934 Yale College graduate, Saarinen would have shared the exhilarating experience of football games at the Yale Bowl, which was completed in 1914. Indeed, Ingalls pays a kind of hidden homage to the Bowl in the way that its interior too was formed by excavating earth from below the entry level and piling it up around the edge of the hole. Both buildings are essentially craters, one (the Rink) with a remarkable roof, the other (the Bowl) without.

Attending a game, especially The Game (Harvard vs. Yale), in the sports-crazy pre-World War II decades was about as intensely communal an experience as American culture could muster. When the stadium opened, it could seat 70,869 spectators, and many a game saw not only that number but also standees by the thousands. It was not only the sheer number of people that made the experience intense by the form of the Bowl and what and whom one saw there, beyond the football game.

Charles A. Ferry (1852-1924), who designed the Yale Bowl, was not an architect, but a Yale-educated engineer. He conceived the Bowl not as steel-framed, a variant on standard engineering bridge-building technology, nor in reference to some revered, supposedly appropriate, historical precedent such as the Colosseum in Rome, a common practice of the day. The Bowl’s basic structure draws upon the technology of municipal water system reservoirs. Forming it as an ovoid earthen crater with a thin concrete liner, Ferry made a huge, fireproof device that allowed large numbers of people to view games and crowds to flow in and out as smoothly as water in a good city hydraulic system. Furthermore, the seating was not broken up into various-leveled decks set at different angles to the playing field, as at Babe Ruth’s Yankee Stadium (which had a comparable capacity), but instead were laid out in consistent curves exactly and efficiently cupped toward the action. When the Bowl is full, it is like being in a giant, perfect, concave mirror whose surface is made of human beings.

The Yale Football Association organized itself in 1872 [See “Walter Camp, the Father of American Football,” Summer 2018], and it is arguable that for at least parts of the next century or so the team was followed as avidly by New Haven-area citizenry as by the Yale community. At the best of times the Bowl afforded — and can still afford today — a gathering place that makes the University more of, and not only in, New Haven. The streets connecting the Bowl to the Yale campus become more communal on those days, as student groups walk the mile and a half between the two, through fallen autumn leaves.

The upper rim of the Bowl, unlike that of many stadia, is held level expect for press boxes and the scoreboard. Consequently it is impossible to escape the sense of the sky as an even larger bowl overhead. The earthly world outside the game is not altogether cut off from view, but what one sees is timelessly geological, not manmade: the red cliffs of East Rock and West Rock, reminders of New Haven’s and Yale’s particular place in the world.

Football and hockey are basically methods of trying to find grace through rough, physically violent, but perhaps also smart, means. This is true for individual players and for the communities they represent. Ingalls Rink and the Yale Bowl are the best sort of examples of how buildings made for games can help their communities, in quiet or in troubled times, find out again who they are and where they might go.

Patrick Pinnell is an architect and planner, a graduate of Yale College and the Yale School of Architecture. A second updated edition of his The Campus Guide: Yale University is in preparation.