(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Winter 2019-2020

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

Architect Philip Johnson first saw the five-acre piece of land where he would build his Glass House in the winter of 1945-1946, shortly after the end of World War II. Johnson made his way on foot downhill through trees until he came to a shelf that dropped away over a cascade of boulders to a lower landscape. He knew it would be an ideal place for his yet-to-be-designed house.

Seventy years later, this promontory on the western side of the Glass House provides an astonishing view of the now-49-acre property that includes not just the Glass House but seven other buildings, seven architectural follies, three vernacular houses, two large outdoor sculptures, and various objects placed in the landscape—not to mention the treasures inside. The collection of paintings and sculpture acquired by Johnson and his longtime partner, David Whitney, a renowned curator, includes work by John Chamberlain, Jasper Johns, Bruce Naumann, Robert Rauschenberg, Julian Schnabel, Cindy Sherman, Frank Stella, Andy Warhol, and many other art-world disruptors and re-calibrators.

Each of the buildings and structures represents a radical idea or a shift in the design trends and theories of 20th-century architecture. At the same time, the site is rich in historical references. Johnson’s love of the ancient world and classical architecture is evident throughout the site. Everything was experimental; he was building for himself but also working out solutions to problems for larger commissions. As Hilary Lewis, now chief curator and creative director at the Glass House, wrote in her introduction to Philip Johnson: The Architect in His Own Words (Rizzoli,1994), “Johnson is enamored of the effects created by the manipulation of scale, form, and proportion, and this obsession often results in quirky but beautiful forms.” His engineers and Port Draper, the builder who worked closely with him from 1968 on, often had to innovate, seeking out the most effective materials, structural forms, methods, and finishes during the construction process. Johnson, whose lifetime (1906—2005) spanned the 20th century, called the place his “fifty-year diary.”

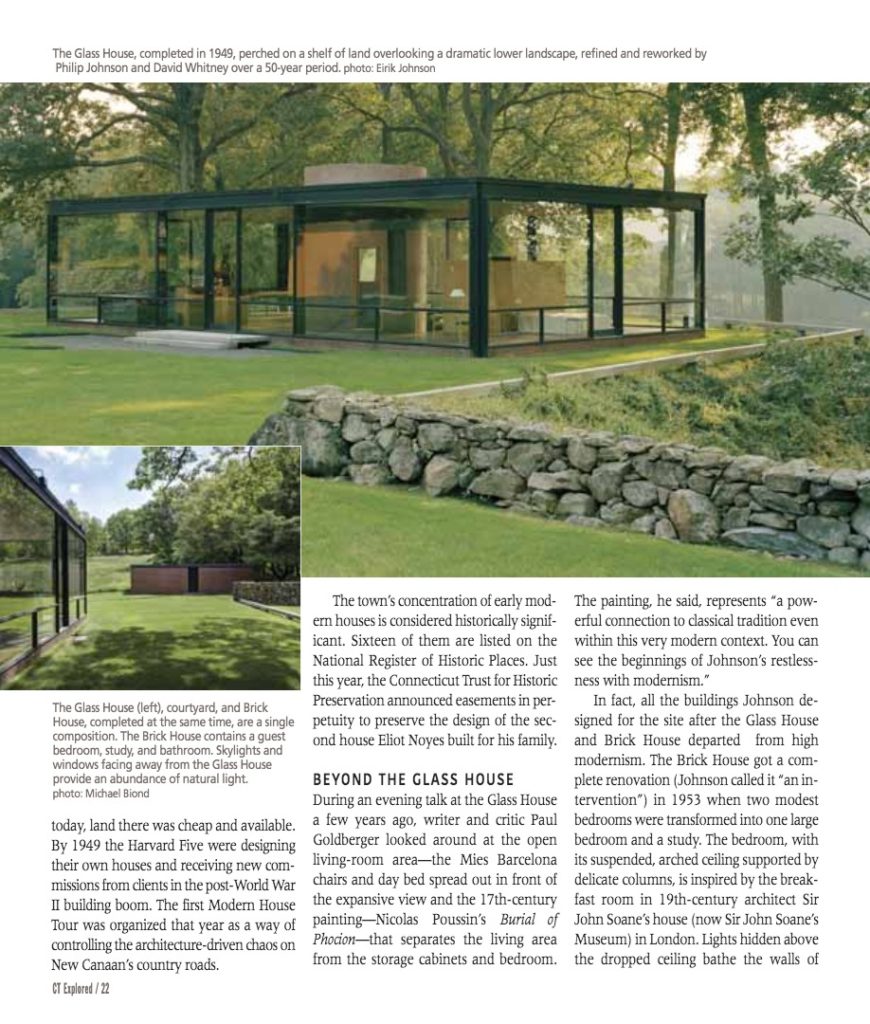

The Glass House and Brick House, the first structures on the site, were designed and built together as one composition. Stover Jenkins and David Mohney write in The Houses of Philip Johnson (Abbeville Press, 2004), “By virtue of its closed surfaces and remote siting, the [Brick] House is so self-effacing it almost disappears.” They stress the powerful abstract space created between the two structures and describe the Brick House as a “foil for its crystalline counterpart.” Johnson often said the front of the Brick House serves as a repoussoir or pushing-off point that sets the viewer on the angled approach to the Glass House. The space between the two buildings functions as a courtyard; this is the one spot on the site where the grass is kept meticulously mowed in baseball-field diagonals.

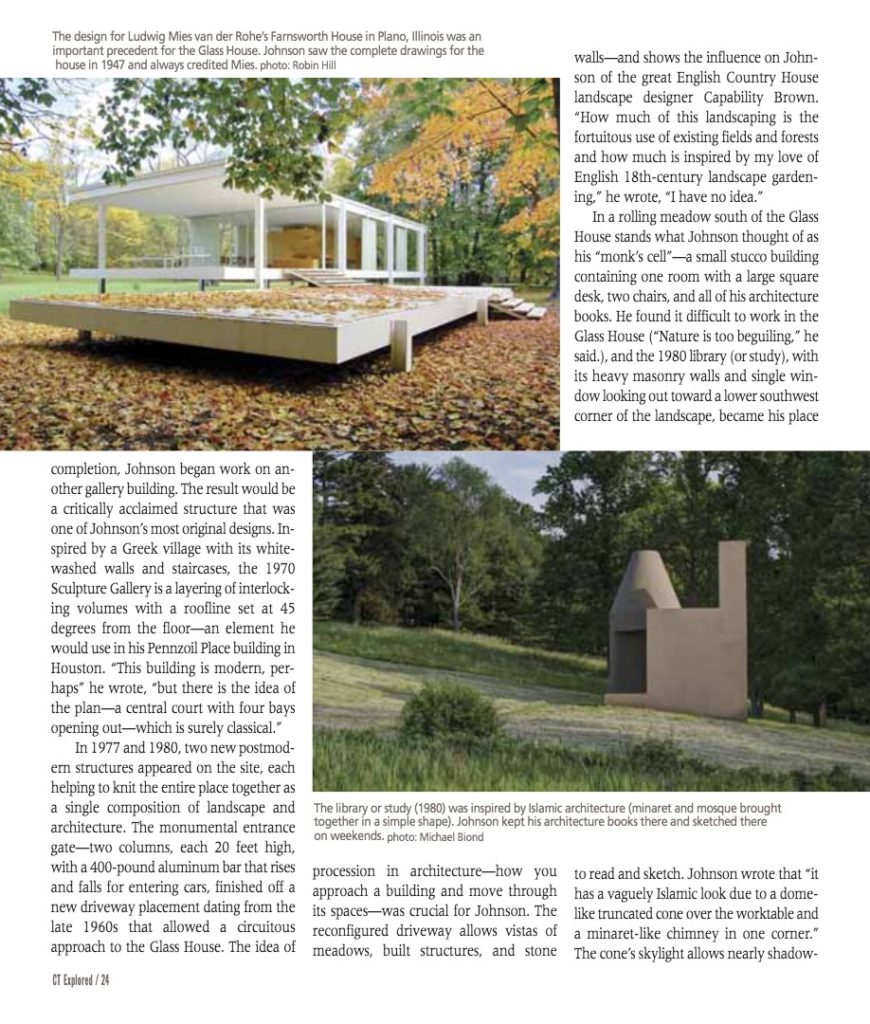

In “House at New Canaan” in Architectural Review (1950), Johnson acknowledged his debt to Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, whose Farnsworth House he had seen fully designed on paper. Johnson and Mies discussed the idea of designing a glass house as early as 1945, and the Farnsworth House in Plano, Illinois (which is, like the Glass House, a site of the National Trust for Historic Preservation) was Johnson’s model. “It was not until I had seen the sketches of the Farnsworth House that I started the three-year work of designing my glass house. My debt is therefore clear,” he wrote. The two houses, however, differ in significant ways. The Glass House sits solidly on the ground like a Greek temple. The Farnsworth house, built in a flood plain, has a structure that lifts its floor off the ground. It floats between the two planes that make up the floor and ceiling. The white Farnsworth House also has an entirely different impact than the black, painted-steel structure of the Glass House, which almost disappears, opening to a 360-degree view of sloping land, stone walls, tall trees, and meadows.

Though the Farnsworth House preceded the Glass House in concept, construction on the Glass House was finished first, in 1949. It caused weekend traffic jams on New Canaan’s local roads as New York magazine editors, architects, architecture students, and curious others rushed to get a glimpse of it.

New Canaan had already become a testing ground for residential mid-century modern design. Johnson bought his land in New Canaan after Eliot Noyes and Marcel Breuer moved to the town. Johnson, Landis Gores, and John Johansen followed. This group, known as the Harvard Five (all were students or faculty at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design), was soon joined by Yale-educated Victor Christ-Janer, Jens Risom, the Danish furniture designer who came to the U.S. in the 1930s, and John Black Lee, educated in naval engineering and mathematics at Brown University. The young architects bought land in New Canaan because, incredible as it seems today, land was cheap and available.

By 1949 the Harvard Five were designing their own houses and receiving new commissions from clients in the post-World War II building boom. The first Modern House Tour was organized that year as a way of controlling the architecture-driven chaos on New Canaan’s country roads.

By 1949 the Harvard Five were designing their own houses and receiving new commissions from clients in the post-World War II building boom. The first Modern House Tour was organized that year as a way of controlling the architecture-driven chaos on New Canaan’s country roads.

The town’s concentration of early modern houses is considered historically significant. Sixteen of them are listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Just this year, the Connecticut Trust for Historic Preservation announced easements in perpetuity to preserve the design of the second house Eliot Noyes built for his family.

Beyond the Glass House

During an evening talk at the Glass House a few years ago, writer and critic Paul Goldberger looked around at the open living room area—the Mies Barcelona chairs and day bed spread out in front of the expansive view and the 17th-century painting—Nicolas Poussin’s Burial of Phocion—that separates the living area from the storage cabinets and bedroom. The painting, he said, represents “a powerful connection to classical tradition even within this very modern context. You can see the beginnings of Johnson’s restlessness with modernism.”

In fact, all the buildings Johnson designed for the site after the Glass House and Brick House moved away from high modernism. The Brick House got a complete renovation (Johnson called it “an intervention”) in 1953 when two modest bedrooms were transformed into one large bedroom and a study. The bedroom, with its suspended, arched ceiling supported by delicate columns, is inspired by the breakfast room in 19th-century architect Sir John Soane’s house (now Sir John Soane’s Museum) in London. Lights hidden above the dropped ceiling bathe the walls of Fortuny cotton in a twilight glow of indirect light. A sky-lit bathroom of black-and-white figured marble features a Greek metope design near the ceiling. (The building is closed to tours at the moment as it awaits long-needed restoration and conservation.)

“Every grownup child should have a playhouse,” Johnson said in his essay “Full Scale False Scale” (Show Magazine, 1963), “and the Pavilion on the pond is mine.” The Pavilion, built in 1962 while Johnson was working on the New York State Theater (now the Koch Theater) at Lincoln Center, shows the architect building for pleasure on his own property and at the same time working out design problems for a larger project. The Pavilion—with its construction of prefabricated concrete arches and roof sections on a poured-concrete base—is made up of “8-foot squares arranged more or less like a Mondrian,” as Johnson noted in his preface to Philip Johnson: The Glass House(Pantheon Books, 1993). The Renaissance arches form a configuration of spaces and columns against the reflections of the water, and this structure is, more than anything else, an experiment in architectural scale, though Johnson was also trying, as he also noted, to find the best way to turn a corner with those Renaissance arches “to avoid the problem of ‘disappearing’ arches in the interior corners of the arcades.” The structure is half to three-quarters scale; the ceilings are about 5 feet, 10 inches high. In his essay on scale, he explained, “A tall person cannot stand in it, an ordinary person can walk around, and a child feels like a king.”

“Every grownup child should have a playhouse,” Johnson said in his essay “Full Scale False Scale” (Show Magazine, 1963), “and the Pavilion on the pond is mine.” The Pavilion, built in 1962 while Johnson was working on the New York State Theater (now the Koch Theater) at Lincoln Center, shows the architect building for pleasure on his own property and at the same time working out design problems for a larger project. The Pavilion—with its construction of prefabricated concrete arches and roof sections on a poured-concrete base—is made up of “8-foot squares arranged more or less like a Mondrian,” as Johnson noted in his preface to Philip Johnson: The Glass House(Pantheon Books, 1993). The Renaissance arches form a configuration of spaces and columns against the reflections of the water, and this structure is, more than anything else, an experiment in architectural scale, though Johnson was also trying, as he also noted, to find the best way to turn a corner with those Renaissance arches “to avoid the problem of ‘disappearing’ arches in the interior corners of the arcades.” The structure is half to three-quarters scale; the ceilings are about 5 feet, 10 inches high. In his essay on scale, he explained, “A tall person cannot stand in it, an ordinary person can walk around, and a child feels like a king.”

When the Pavilion was new, it was painted white. It had a gold-leaf ceiling and a fountain, a jet d’eau, that sent a spray of water high above the pond. Smaller trickle fountains animated a miniature center court. To get onto the structure, Johnson had to leap from the edge of the pond. This architectural folly served as a study of form that he incorporated into other buildings, including the Sheldon Museum of Art in Lincoln, Nebraska, and the Beck House in Dallas.

Construction soon began on the first of the two art galleries. The 1965 Painting Gallery was built on grade, and earth was pushed up against the walls to create a berm. The plan, a three-leaf-clover shape, is hidden to those who approach the red sandstone entrance—modeled on the Treasury of Atreus (an ancient tomb in Mycenae)—cut into the hillside. Visitors enter through what Lewis calls an elegant Johnson design element—doors that are too slender and too tall—and after stepping into the compressed space of a modest vestibule, emerge into an enormous high-ceilinged space with three carousels of moving panels for large paintings. The panels are another idea gleaned from Sir John Soane’s house, where Old-Master paintings in their ornate frames turn on a moving system. But Johnson’s panels are the basis for the Painting Gallery’s entire structure and form, and standing in the cavernous space is a singular experience. For Johnson and Whitney, it was a place where many paintings could be stored, even as they viewed only a few at a time. For a public museum, this revolving design plan would pose security issues—visitors could slip behind the panels unseen—but because the Glass House was his home, Johnson was free to experiment.

Because of the revolving panels, there is very little space in the Painting Gallery for sculpture, so three years after its completion, Johnson began work on another gallery building. The result would be a critically acclaimed structure that was one of Johnson’s most original designs. Inspired by a Greek village with its white-washed walls and staircases, the 1970 Sculpture Gallery is a layering of interlocking volumes with a roofline set at 45 degrees from the floor—an element he would use in his Pennzoil Place building in Houston. “This building is modern, perhaps” he wrote, “but there is the idea of the plan—a central court with four bays opening out—which is surely classical.”

In 1977 and 1980, two new postmodern structures appeared on the site, each helping to knit the entire place together as a single composition of landscape and architecture. The monumental entrance gate—two columns, each 20 feet high, with a 400-pound aluminum bar that rises and falls for entering cars, finished off a new driveway placement dating from the late 1960s that allowed a circuitous approach to the Glass House. The idea of procession in architecture—how you approach a building and move through its spaces—was crucial for Johnson. The reconfigured driveway allows vistas of meadows, built structures, and stone walls—and shows the influence on Johnson of the great English Country House landscape designer Capability Brown. “How much of this landscaping is the fortuitous use of existing fields and forests and how much is inspired by my love of English 18th-century landscape gardening,” he wrote, “I have no idea.”

In a rolling meadow south of the Glass House stands what Johnson thought of as his “monk’s cell”—a small stucco building containing one room with a large square desk, two chairs, and all of his architecture books. He found it difficult to work in the Glass House (“Nature is too beguiling,” he said.), and the 1980 library (or study) with its heavy masonry walls and single window looking out toward a lower southwest corner of the landscape became his place to read and sketch. Johnson wrote that “it has a vaguely Islamic look due to a domelike truncated cone over the worktable and a minaret-like chimney in one corner.” The cone’s skylight allows nearly shadowless light over the worktable. Another structure that influenced its austere form is Aldo Rossi’s 1979 floating Teatro del Mondofrom the Biennale in Venice. There was never a paved path to the library. In spring and summer the meadow grasses wave ocean-like all around it.

Below the library/study is another architectural folly, built in 1984. It is a 15-foot-by-15-foot structure made of chain-link fence and shaped like a child’s drawing of a house. An homage to Frank Gehry, who used chain link in his early Santa Monica house, it was constructed on the foundation of an old cow barn or tool shed. It is in two halves that almost come together at the center, a postmodern broken pediment. The Ghost House, as it was called, was an enclosed garden where Whitney grew lilies. It was somewhat deer-proof, though the opening in the middle is just wide enough for a small deer to fit through.

The Glass House’s spectacular western view looks out over the Pavilion, and farther out in the landscape is the 1985 Lincoln Kirstein Tower, named for Johnson’s close friend from his undergraduate days at Harvard University. Kirstein was a poet and a founder of the New York City Ballet. Johnson thought of ballet as an art form that makes a kind of architecture of the body. The tower, made of concrete block and rebar, nestles between mature tree trunks and the dappled light of Johnson’s idealized forest. Though the landscape looks entirely natural on first glimpse, trees have been trimmed of scruffy lower branches, and infinite forest hollows surround the 31-foot stairway to nowhere. Johnson climbed the tower until he was 80 years old.

The final major project on the site is Da Monsta, Johnson’s 1995 deconstructivist building, designed shortly after the 1988 exhibition of deconstructivist architecture at MoMA. The form is a Frank Stella-inspired shape from a grouping of architectural structures (unbuilt) that Stella conceived for a cultural park in Dresden (First Model Kunsthalle Dresden, 1991). Johnson was increasingly interested at the time in the work of Frank Gehry, whose influence can also be seen here. He was also looking back to the visionary German Expressionist forms of Hermann Finsterlin. The smooth hand-troweled spray-concrete surface is painted barn red and black. Da Monsta has the two-part sculptural form of a pavilion and a tower and a tilting, curvilinear, animal-like shape. In the delightful 1995 documentary by Checkerboard Films, Diary of an Eccentric Architect, Johnson said of Da Monsta, “It’s like a good horse—you want to pat it every day.”

When he designed this building, Johnson had already donated his property to the National Trust for Historic Preservation with a lifetime tenancy agreement: the Glass House would be his home, and, after his death, would become a public place. He knew that future tours could use Da Monsta as a landing point, perhaps with an introductory video.

And there is more: the three vernacular houses Johnson and Whitney retained, the 1955 circular swimming pool, a 1971 concrete ring that is Donald Judd’s first outdoor, site-specific sculpture, Julian Schnabel’s fallen totem in bronze, Ozymandias, a stone table, a minimalist wooden dog house, and a Lutyens bench—painted orange and placed far into the woods.

As Vincent Scully wrote in “Philip Johnson, The Glass House Revisited,” in Architecture magazine, (1986), “His place now joins, as no one thirty years ago could ever have thought it would, not only Taliesin West but Monticello too as a major memorial to the complicated love affair Americans have with their land.” The old stone walls and the sloping landscape are part of Connecticut’s past and present that Johnson, with his finely tuned and eccentric forms, connected with an infinite constellation of architectural references and ideas. What is playful here is also daring and serious. The landscape was his canvas and his context; the individual structures, as astonishing as they are, each play a role in an endlessly nuanced exploration of architecture and landscape architecture. As he said to Hilary Lewis, who worked with Johnson on his publications and memoirs, “To me, it’s one art…I don’t find the line drawn anywhere.”

Gwen North Reiss is a writer and poet who has written frequently about modern architecture. She is an educator at The Glass House.

Read More!

Philip Johnson in His Own Words, Winter 2009-2010

Modernism in Connecticut, Winter 2009-2010

Eliot Noyes, Design Pioneer, Spring 2020

Read more about the historic Connecticut landscape on our TOPICS page

Read more about Connecticut’s Art History on our TOPICS page