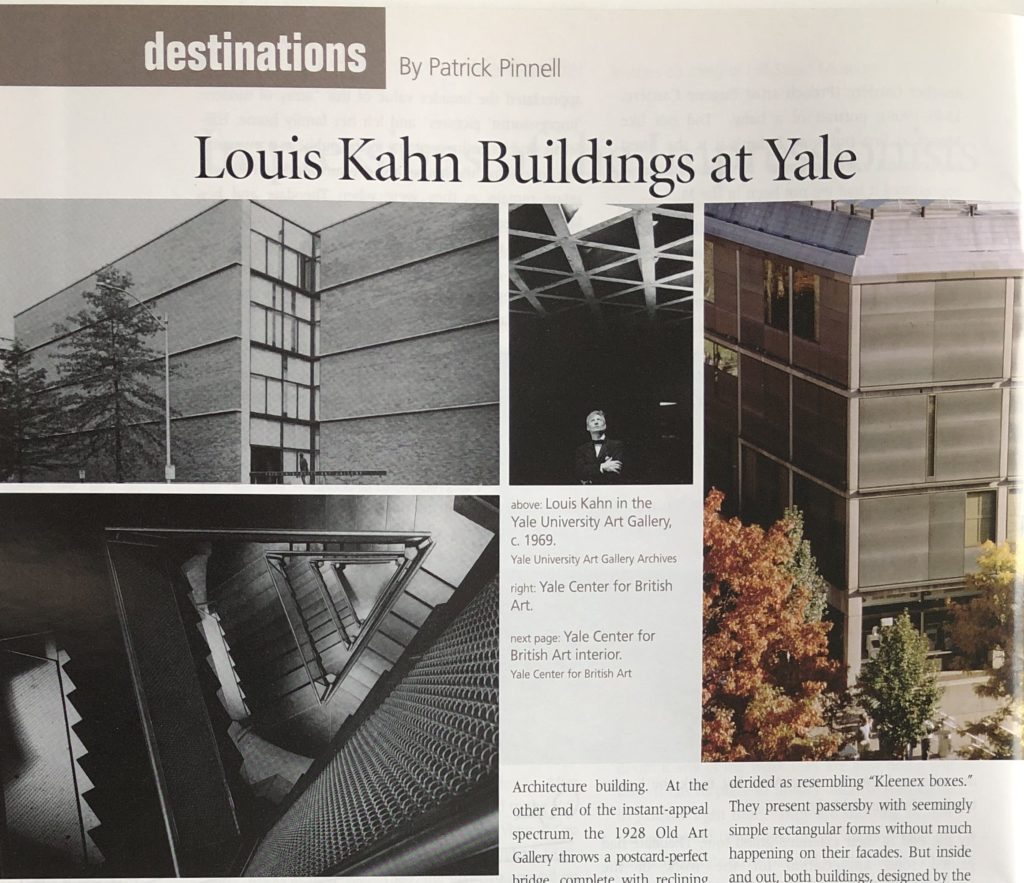

top left: The Yale University Art Gallery’s Chapel Street entrance, c. 1969. below left: Staircase under construction at the Yale University Art Gallery, c. 1954. photo: Lionel Feininger; center: Louis Kahn in the Yale University Art Gallery, c. 1969. Yale University Art Gallery Archives; right: Yale Center for British Art.

By Patrick Pinnell

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Winter 2006/2007

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

From the western corner of the New Haven Green, a short walk along Chapel Street brings you to the cluster of buildings that are home to Yale’s visual and performing arts. It is a place for enjoyment and exploration, not only of the art and drama to be found there, but also of the highly varied architecture housing all the offerings. People react strongly, for example — one way or another — to the rough corduroy concrete of the 1963 “Brutalist” Art & Architecture building. At the other end of the instant-appeal spectrum, the 1928 Old Art Gallery throws a postcard-perfect bridge, complete with reclining nude muses, over High Street. Both buildings just plain demand attention.

Two of the area’s most interesting and important pieces of architecture are surprisingly less eye-catching. The newer (at Yale, a half-century qualifies as new) art galleries flanking Chapel Street — the Yale Art Gallery of 1953 and the Yale Center for British Art (familiarly known as the British Art Center, or BAC), opened in 1977 — have both been derided as resembling “Kleenex boxes.” They present passersby with seemingly simple rectangular forms without much happening on their facades. But inside and out, both buildings, designed by the great architect Louis Kahn (1901 – 1974), offer lessons in architecture as quiet but memorable poetry for those who make the effort to look.

The older of the two, the Yale Art Gallery, reopens December 10 after a scrupulous, years-long renovation. Built not long after World War II, at a time when most Modern architecture was designed to look light, open, and machine-like, the Art Gallery instead projects a feeling of weight, solidity and permanence. Kahn wanted it to give the sense of enclosing protection that older art museums (such as the Old ArtGallery, to which it was an addition) had tried to attain by drawing upon historical styles. Kahn’s greatness as an architect derives from that achievement: without fakery, he brought a sense of deep time, of enduring things seen in always changing light, back into contemporary architecture.

The Art Gallery’s windowless brick Chapel Street facade is too abstract for its own good. It gives nothing to the street, and it doesn’t add much to this early fruit of Kahn’s lifelong search for a way to combine weight and light. Inside, though, the mysteriously hovering coffered concrete ceilings are another story. Clearly very heavy, the ceilings have so little visible support that it seems the art itself, lit by spotlights concealed within the coffers, is generating a force field to hold them up. The recent renovation stripped away a lot of stuff that over the years had come to obscure that ceiling, so important both to the gallery and to Kahn’s larger quest. In particular, the building has returned to his original way of displaying paintings on “pogo panels,” stilt-legged walls that do not reach all the way to ceiling or floor and so don’t distract us from the overall space.

The building’s rear wall, in striking contrast to the Chapel Street face, is all glass and steel. It opens onto a second-level sculpture courtyard that was there before Kahn’s building. One of the hidden glories of Yale University, the pre-existing court is clearly a place the architect wanted to engage as a part of the meaning of his own design. The court can be accessed from High Street by way of an unmarked passage skirting just north of the Skull and Bones “tomb,” still another of Yale’s reticent strong-boxes. It is well worth the trouble to seek out. The courtyard ground is raised a full level above the city streets around it; astonishingly, it contains three of the Elm City’s few surviving elm trees. For Kahn, the old courtyard adjoined to his gallery must have been a kind of secret doorway back into tradition, a way of gaining beauty from age without risking its creeping paralysis.

On the other side of Chapel Street, the BAC was completed in 1977, almost a quarter century after the Art Gallery. It was Louis Kahn’s last design. He died of a heart attack in a subterranean Penn Station men’s room when the building’s concept was essentially complete but its details not yet fully worked out. The two Yale galleries are the beginning and end brackets of his mature career.

The BAC is less about weight and sense of enclosure — the concerns evident in the Art Gallery — and more about the appreciation of materials, both artistic and architectural, as they appear in changing weather and light. The pewter-like metal panels that clad the building can be leaden at noon, then glow an almost molten red-gray at sunset. Inside, Kahn’s concrete ceiling coffers are, paradoxically, both larger and heavier than those at the art gallery, yet also lighter, since these have complexly shielded skylights at their centers. The light coming down through the openings varies subtly as clouds come and go, a changing wash on the oak and linen panels where the English art collection of the donor, Paul Mellon (of the banking family), feels as though hung in a large, but unpretentious and generous, country house. It is a place that lengthens a visitor’s attention span by creating the sense that things here are really worth watching, instant to instant. Calmly, the present moment joins up with the long history and beauty of the art and the building.

When Yale first proposed to build the BAC, no stores or restaurants were included in the design. The feeling was that somehow the mere commercialism of such uses compromised the seriousness of a building for fine art. Fortunately, under pressure from the city, Yale relented. Today’s bustling street-level life now can be seen as contributing to, not detracting from, the building’s central meaning, restating in public its internal contrast of the slow-changing and the ephemeral. In hindsight, the British Art Center’s opening itself to Chapel Street can also be understood as the symbolic beginning of the university’s positive re-engagement with the city around it. The two Kahn-designed galleries are now part of the rediscovery of something both new and very old: the art of city life.

Patrick Pinnell is an architect, planner, and author of Yale: The Campus Guide.

EXPLORE!

The Yale University Art Gallery

located at the corner of Chapel and High Streets, New Haven

(203) 432-0600; http://artgallery.yale.edu

The Yale Center for British Art

1080 Chapel Street, New Haven

(203) 432-2800; www.yale.edu/ycba.