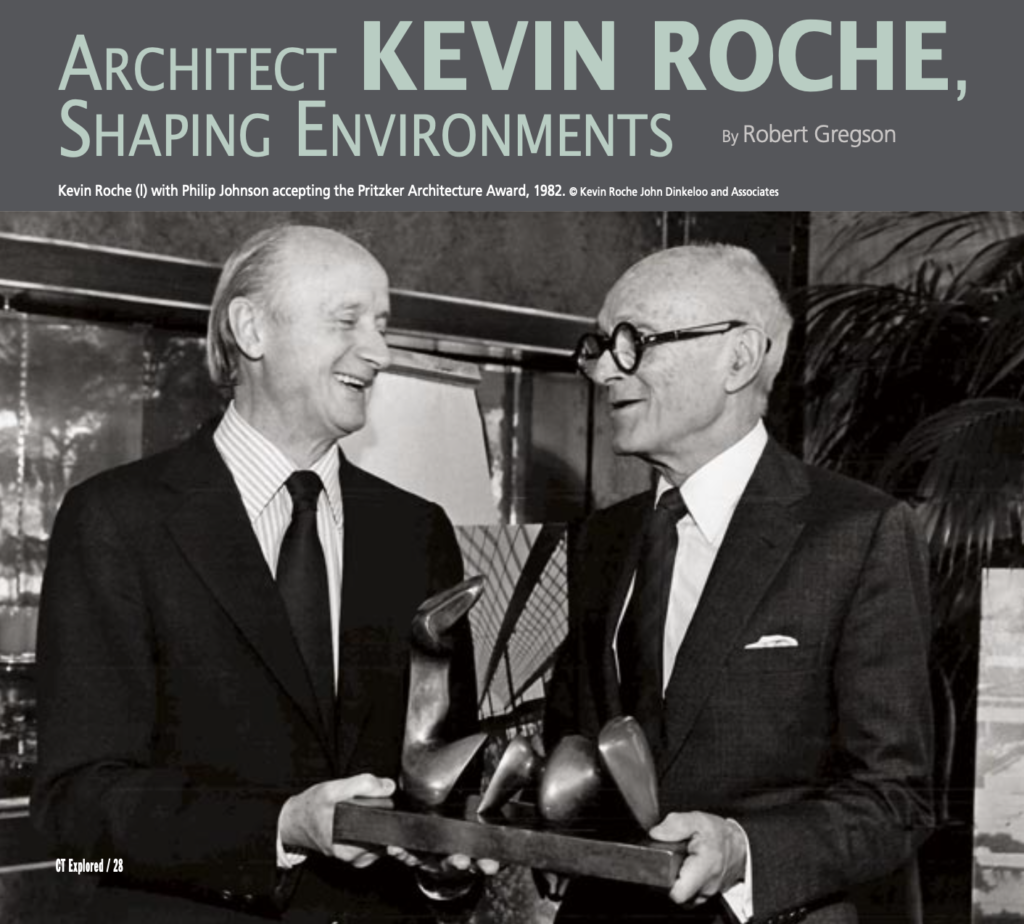

Kevin Roche (l) with Philip Johnson accepting the Pritzker Architecture Award, 1982. © Kevin Roche John Dinkeloo and Associates

By Robert Gregson

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc., Summer 2022

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

In the documentary film Kevin Roche: The Quiet Architect (2017), architect Robert A.M. Stern describes Kevin Roche as “irresistibly nice.” But nice as he may have been, this modest Irish-born American was also a force to be reckoned with in the world of architecture. He designed more than 200 innovative buildings on three continents. His architectural vision mixed pragmatic necessities with humanistic concerns for community and individual productivity. In 1982 Roche was awarded the Pritzker Architecture Prize. Although he won numerous prestigious honors, including the AIA Gold Medal, the Pritzker is considered the profession’s highest honor.

Early Life & Career

Eamon Kevin Roche was born in Dublin, Ireland 100 years ago this year. He was raised in Mitchelstown, County Cork, where his father joined the dairy cooperative movement and started a farm with a large piggery. In The Quiet Architect Roche remembered, “We had several thousand pigs. One of my first jobs was to design a piggery … the pigs loved it.”

He enrolled in the National University of Ireland and received a Bachelor of Architecture degree in 1945. As an ambitious architect he kept a list of leading architects with whom he was eager to work and learn. In 1948 he moved to the United States for graduate study. He applied to Harvard and Yale universities and the Illinois Institute of Technology, where Ludwig Mies van der Rohe was teaching. All three schools accepted him. But it was the presence of Mies, described in Architectural Review as a great teacher, that persuaded him to attend IIT. “Mies was extraordinary,” Roche told editor Thomas Weaver for AA Files, the journal of the Architectural Association School of Architecture. “He was a formidable presence. Somehow he had the ability to convert one in much the same way an evangelist might do.” Despite his respect for Mies, he confessed, “I was really quite disappointed in the school” and, feeling he had learned all he could, he left IIT in 1949.

Determined to be part of the international team designing the United Nations building in New York, Roche talked his way onto the project. In Francesco Dal Co’s Kevin Roche (Random House, 1985), Roche is quoted as saying, “I badgered the planning people at the UN Planning Office until they gave me a job.” Under the leadership of Wallace K. Harrison, the world’s most renowned architects collaborated on the design. Roche’s job turned out to be less glamorous than he might have imagined. It involved menial design tasks and clerical work such as filing drawings. Then, after a Christmas visit to his family in Ireland, he returned to New York only to find he’d been fired. His son Eamon, a founding member and managing director of Roche Modern in New Haven, reflected in a conversation with me, “That must have been tough, but as mild mannered as he was, he was also so driven. I’m sure there wasn’t a lot of doubt in his mind that he was going on to great heights, it was just so much a part of his nature.” A friend at the U.N. recommended him to 39-year-old architect and industrial designer Eero Saarinen, who was looking for an assistant.

Working With Saarinen

Roche’s life changed when he joined Eero Saarinen and Associates in 1950. He became principal designer from 1954 until Saarinen’s death in 1961. Richard Knight explained in Saarinen’s Quest (William Stout Publishers, 2008) that “Saarinen conferred no official titles, even on himself.” In The Quiet Architect Cesar Pelli, a colleague in Saarinen’s office, remembered, “Kevin was sort of Eero’s alter-ego. Many of his ideas were incorporated into what Eero was doing.” For seven years Roche, along with Pelli, John Dinkeloo, Gene Festa, Joe Lacy, Warren Platner, and other talented architects, produced buildings for Eero Saarinen and Associates that expanded the definition of modern architecture, and Roche was central to the process.

J. Irwin and Xenia Miller House, Columbus, Indiana, commissioned in 1953, with its innovative sunken living room. photo: Robert Gregson

In the decade after World War II the United States enjoyed an expanding economy and many opportunities opened for architects. Roche admired Saarinen’s willingness to allow young architects to mature and grow. While Saarinen was busy with large commissions, Roche was given the chance to oversee projects on his own. An early project was a house for the chairman of Cummins Engine, J. Irwin Miller and his wife Xenia Simons Miller. Located on 13 acres in Columbus, Indiana, the house is credited to Saarinen with Roche as collaborator and the lead designer, as Saarinen Houses (Princeton Architectural Press, 2014) documents. The flat roof with deep overhanging eaves is crossed with continuous skylights. The ample conversation pit started a trend. A storage wall in the central living space showcased the Millers’ collection of folk art and objects (including a special cabinet for their antique Stradivarius violin). The base of the massive dining table was integrated into the floor. The center of the table featured a circular fountain in which Xenia floated flowers. Textile designer Alexander Girard was engaged to create a colorful interior including carpets, upholstery, and drapes. Landscape architect Dan Kiley was hired to visually integrate the building with the landscape using rows of trees and bushes to frame views and vistas. The Millers loved the house and became avid supporters of Roche’s work. Irwin engaged Roche to design Cummins Engine’s corporate offices and several other buildings nearby.

Roche embraced Saarinen’s innovation of creating large-scale study models of buildings under design. In his introduction to Saarinen’s Quest, Pelli describes Saarinen’s use of these models to accurately experience how the interior of a building would feel. Saarinen started this practice during the design of Ingalls Rink at Yale University in 1956. [See “Destination: Ingalls Rink and the Yale Bowl,” Fall 2009.] Creating an enormous model was particularly helpful in understanding the complex design of the TWA Flight Center at John F. Kennedy International Airport in New York (1956 – 1962), with its flowing forms. Roche made a model room a key part of his design practice for the rest of his life.

By 1961 the location of Saarinen’s office in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan was beginning to be a problem. To be closer to consultants and projects, Saarinen and his partners planned to move the office east. After an extensive survey of locations from Boston to Washington, they chose Hamden, Connecticut, which was close to Yale, and purchased a 1906 rusticated Teutonic castle-like mansion. A large flexible space was added for the design studio. By 1960 a dozen projects were underway, including some of Saarinen’s best-known works such as the TWA terminal, Dulles International Airport (1958 – 1962), CBS headquarters (1960 – 1964), John Deere headquarters (1955 – 1963), and the Gateway Arch in St. Louis (1947 – 1965).

Then, in 1961, during the transition, tragedy struck. In Jayne Merkel’s Eero Saarinen (Phaidon Press, 2005), architect Gene Festa recalled a meeting with Saarinen, who was suffering from a headache so severe he had to leave. Saarinen was diagnosed with a brain tumor and died during an operation. “It was a shocking moment. There was no forewarning,” said critic historian Shane O’Toole in The Quiet Architect. With Saarinen gone and the office in transition, the design and management fell to Roche, Lacy, and Dinkeloo to complete the projects. As Roche said to Weaver, “Words can’t explain how devastating that moment was. But at the same time there seemed like there was so much to do. This helped me get through it.”

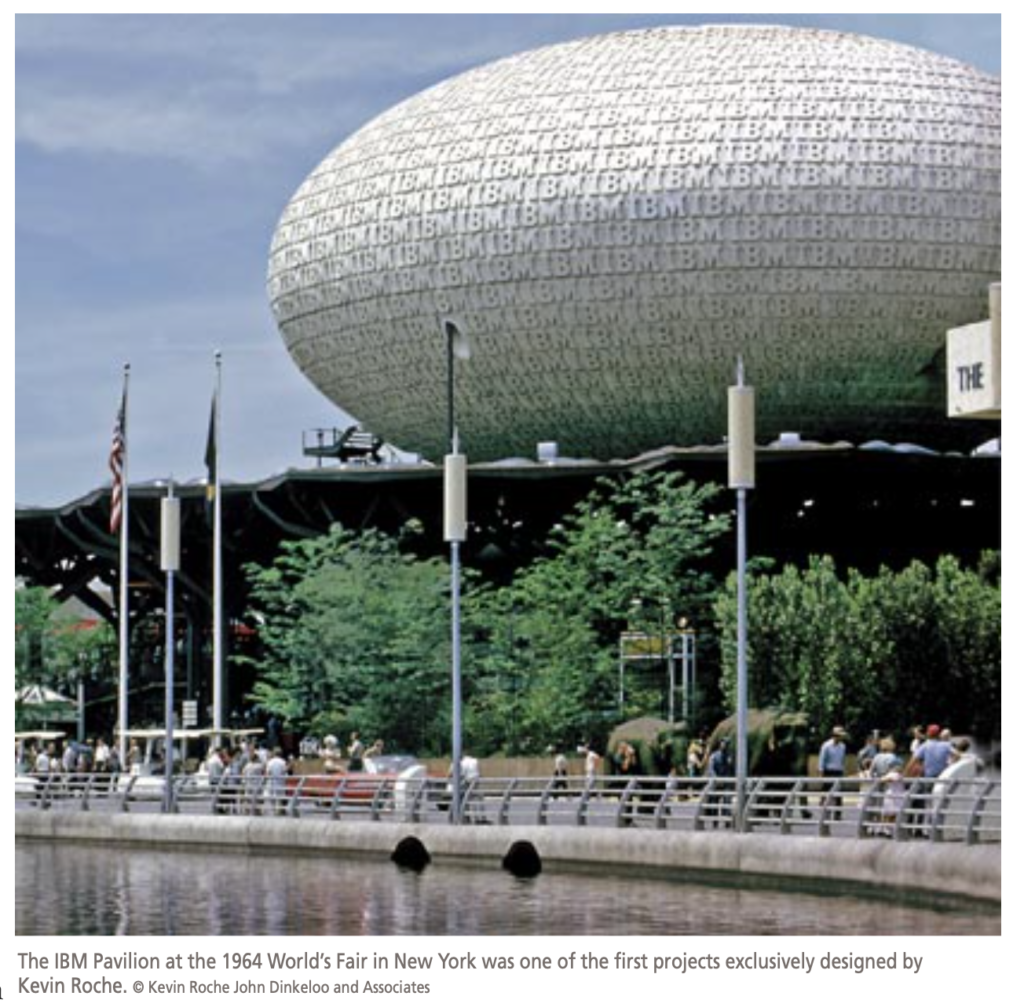

The IBM Pavilion at the 1964 World’s Fair in New York was one of the first projects exclusively designed by Kevin Roche. © Kevin Roche John Dinkeloo and Associates

The IBM Pavilion for the 1964 New York World’s Fair was one of many projects in the planning stage. After Saarinen’s death, IBM continued with Roche. Roche’s fanciful egg-shaped structure rests atop a forest of 45 Cor-ten steel tree-like supports. Visitors entered rows of bleachers on the ground level, then were raised up into the egg-dome with hydraulic lifts. Inside was a dazzling multi-screen show with projections designed by Charles and Ray Eames touting the world of our computerized future.

As principal designer, Roche shouldered the twin burdens of fulfilling Saarinen’s legacy and developing his own projects. During the five years he oversaw completion of Saarinen’s designs, the firm needed to acquire new projects to stay in business. Because of Saarinen’s death, the office almost lost the chance to compete for the design of the Oakland Museum in California. Roche had not yet proven himself on his own. As a courtesy, the committee allowed the firm to compete in the field of 37 prominent architects. The firm’s breakthrough entry, designed by Roche, was selected.

The Oakland Museum, completed in 1966, was Roche’s first major professional success and revealed his philosophy of connecting the community within the function of the design. “Buildings grew out of the program, the site, and the clients’ use,” architect Wes Kavanagh, who spent 42 years working with Roche, explained in an interview with me. The museum plan is a complex of museums of art, natural history, and cultural history. A public park is incorporated onto its rooftops, which are used for hosting gatherings, concerts, and discussions. In Conversations with Architects (Praeger Publishers, 1973) Roche talked about how his proposal helped define how the project would benefit Oakland. He said, “We made a masterplan connecting our site to the heart of the city. The whole thing comes together as a total concept.” Incorporating natural elements became a hallmark of his work.

A New Era as KRJDA

After Lacy retired in 1967 Roche established a partnership with Dinkeloo and formed Kevin Roche John Dinkeloo Associates (KRJDA). “There would be no point in our existing if we were just trading on Saarinen’s name,” Roche said in Paul Heyer’s Architects on Architecture: New Directions in America (Walker & Company, 1966). When Dinkeloo died in 1981 Roche retained the firm name and the acronym KRJDA.

Roche’s design process was a natural extension of his problem-solving abilities. “There are two kinds of architects––problem solvers versus monument builders. Kevin Roche is the ultimate problem solver,” Jim Henderson, former CEO of Cummins Engines, said in The Quiet Architect. As Kavanagh explains, “Design started with a 3-D model of the site. Site and program were a given. Code compliance, energy efficiency, along with environment, community and client use were the beginning of the creative process.”

The Ford Foundation commissioned KRJDA to design its headquarters in New York in 1968. Kavanagh emphasized to me, “Kevin was very interested in the quality of life in his buildings.” To that end, Roche designed the glass-walled offices to overlook an enormous 12-story enclosed atrium with gardens and trees. This year-round green space provided an interior park for the community as well as staff. The innovative atrium became famous, and the building was recognized in 1968 by Architectural Record as “a new kind of urban space.”

These early successes won KRJDA a reputation as the firm to develop and realize not just a building but an architectural master plan. In 1967 KRJDA was selected as the architect for the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. For 40 years, until his death in 2019, Roche designed additions and reorganized and remodeled galleries. The dramatic pavilion for the Temple of Dendur in 1976 is possibly the best-known of his additions, with its austere setting, reflecting pool, and expansive wall of glass facing Central Park.

Roche designed 10 buildings in New York City. One example is the 40-story glass-walled United Nations Plaza located adjacent to the United Nations Building and composed of two sleek towers that are connected at the ground level. To respect building codes, angled set-backs cleverly add to the shape. It seems ironic that the “office boy” who worked for the United Nations Building architects in 1949 became the designer of this high-rise next door.

Roche in Connecticut

Throughout his career, Roche designed many buildings in Connecticut. In Danbury the 1.3-million-square-foot Union Carbide world headquarters (1976 – 1982) took advantage of its natural site with office clusters that branch off the central core into the landscape, giving every office a window view. Employees were further engaged by being allowed to choose their own work space. Roche created 30 interchangeable office styles with two color options, providing employees a way to personalize their own environment. As Kavanagh put it, “The key question was ‘How do we make their lives better?’”

In 1969 Roche designed the 23-story Knights of Columbus headquarters in New Haven. When the Knights sponsored Pope John Paul II’s visit to the United States in 1995, Roche was asked to design the dias and papal throne for a Mass for 72,000 people to be held at Aqueduct Raceway in Queens, New York. Staff architect John Kordak was assigned to collaborate with Roche. The design incorporated exact specifications from Vatican security and the U.S. Secret Service. An article in The Hartford Courant (September 30, 1995) described the gilded-walnut papal throne by woodworker Arthur T. Foote. Since the Pope suffered from back problems, the seat was a specific height, plus the seat and back were discreetly encased one-quarter-inch ballistic steel to ward off a potential assassin’s bullets. After the visit the throne became part of the Knights of Columbus Museum in New Haven.

In The Quiet Architect, Kevin summed up his philosophy about life, “The worst thing you can do is look back. You want to be looking forward. Watch out where you are going. Never mind where you’ve been.” In his 1982 acceptance speech for the Pritzker Architecture Prize Roche gave an insight into his motivation as an architect. “We should, all of us, bend our will to create a civilization [in]which we can live at peace with nature and each other.” Kevin Roche died in Guilford, Connecticut in 2019. He was 96.

Robert Gregson is an artist and former creative director of the Connecticut Commission on Culture & Tourism. He last wrote “Eliot Noyes, Design Pioneer,” Spring 2020.

Explore!

Read all of our stories about Modernism in Connecticut on our TOPICS page

GO TO NEXT STORY

GO BACK TO SUMMER 2022 CONTENTS