Connecticut in the Civil War

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc.

In the mid-1800s, relations between the North and the South became more and more strained over the issue of slavery and its expansion into new states and territories. Connecticans were divided on the issue.

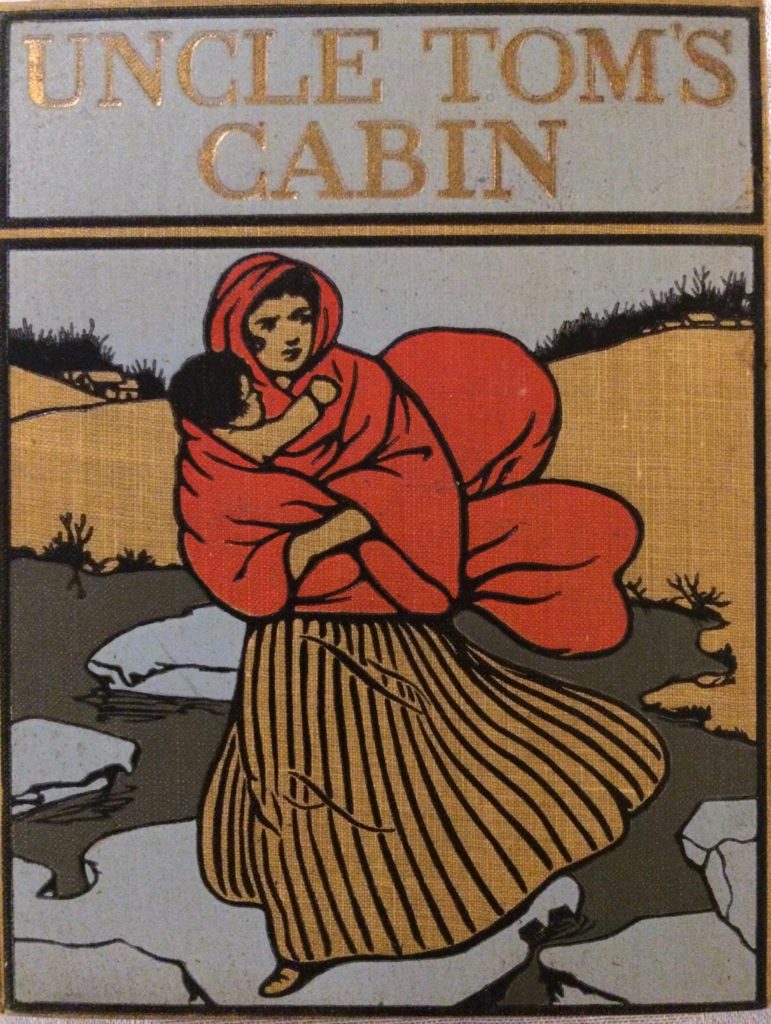

Litchfield, Connecticut-born Harriet Beecher Stowe’s 1852 novel, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, changed many people’s minds against slavery. (She wrote the novel while living in Maine. She moved back to Hartford in 1865 and died there in 1896.) Stowe’s goal in writing Uncle Tom’s Cabin, she said, was to “write something that would make this whole nation feel what an accursed thing slavery is.” Her antislavery novel became an international best seller. She became an international celebrity. Uncle Tom’s Cabin was the best-selling American novel of the 19th century. President Lincoln, upon meeting Stowe, is rumored to have said, “So you’re the little woman who started this great war.”

Read more about her and the impact of her novel here:

But after the Southern states seceded, as many as half of Connecticans opposed the war, according to CCSU history professor Matt Warshauer. Some had strong business ties with the South. Many white people held racist views.

Even if white Connecticans supported the war, they did not necessarily support ending slavery in the South. Some were for preserving the Union—with or without slavery. There were abolitionists in the state who supported the war in order to end slavery, but their numbers were few, according to Warshauer. Litchfield’s John Brown is a famous example. Connecticut’s Black abolitionists had been speaking out for decades. But abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison famously called Connecticut “The Georgia of the North.”

People against the war believed in state’s rights—including the right to have slavery and secede from the Union. This conflict played out in Litchfield’s “Peace” Movement.

The conflict also reveals itself in the race for governor of Connecticut in 1860. That year, pro-Lincoln candidate William Buckingham (who was up for reelection) narrowly defeated pro-state’s rights candidate Thomas Seymour.

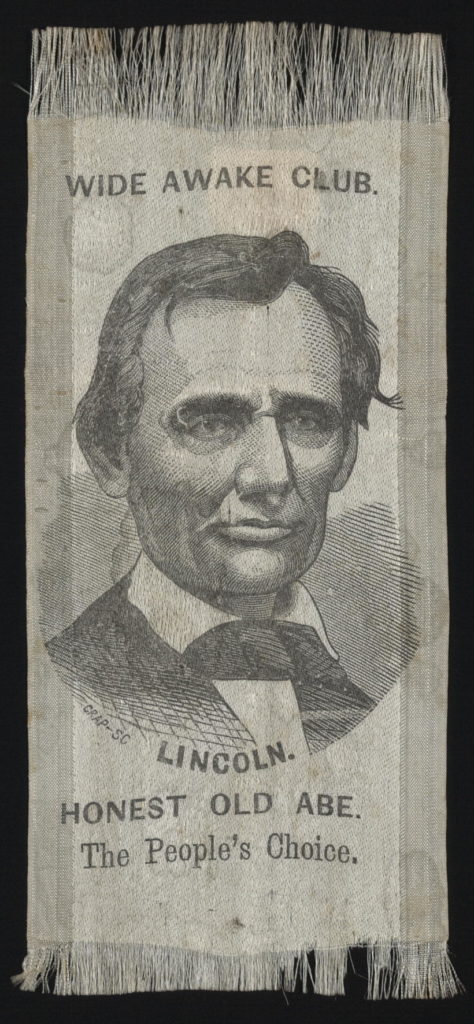

Candidate for President Abraham Lincoln Campaigns in Connecticut

Abraham Lincoln toured Connecticut in 1860 on his way to his narrow victory in 1861.

The Wide Awakes, a club that formed in Hartford to support Lincoln’s campaign and that then spread across the country, was credited with helping Lincoln win the election. It started when Kentucky State Representative Cassius Clay came to Hartford to campaign for Buckingham in March 1860. Clay was a fellow Republican and abolitionist. A torch-light procession formed to lead him to his speech. The marchers wore caps and capes to protect their hair and clothes from the leaky kerosene torches they carried. They made such an impression that they started a movement that spread across the country. They gave themselves the name “Wide-Awakes.”

The end of the war preserved the Union but it did not unite Connecticans around race. An example is the public referendum in 1865 about enfranchising Black men. That year the Connecticut General Assembly proposed to eliminate the word “white” from the qualification for voting. “White” had been part of the state’s voter law since 1814. Since 1814, Connecticut’s Black residents had petitioned the legislature for their right to vote more than 25 times.

“No Taxation without Representation”: Black Voting in Connecticut

Finally, the General Assembly acted to extend suffrage to Black men. But in order to become law, the act was put to a public referendum. In early fall 1865, Connecticut’s white, male voters defeated the proposal. Connecticut only changed its voter laws after the passage of the 15th amendment to the U.S. Constitution in 1870.

Though support for the war was not universal, when it came time to fight, Connecticut responded. About half of Connecticut’s men aged 15 to 50—nearly 56,000—fought in the war, Warshauer estimates. Strikingly, of Connecticut’s 2,200 Black men in that age group, 78% fought in the war, according to Charles (Ben) Hawley [See “Connecticut’s Black Civil War Regiment,” Spring 2011]. In all, more than 5,000 Connecticut men died. Few families escaped the loss of fathers, brothers, and sons. Communities lost many productive workers. The war was brutal and resulted in the loss of an estimated 620,000 soldiers nationwide.

Explore these stories and topics relating to service in the Civil War, including three primary sources:

What was it like to serve in the Civil War?

The Civil War Comes to Town: Madison Meets the Call for Troops

Who was Lincoln’s Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles of Glastonbury?

What was happening on the home front in Connecticut?

When Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, how did Connecticut respond?

Norwich Celebrates the Emancipation Proclamation, Winter 2012-2013

Read all of our stories in the Spring 2011 and Winter 2012-2013 special issues commemorating the 175th anniversary of the Civil War.

Sources:

Connecticut Explored, Spring 2011 and Winter 2012-20313

Matthew Warshauer, Connecticut in the American Civil War: Slavery, Sacrifice, & Survival (Wesleyan University Press, 2011)