By Matthew Warshauer

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. WINTER 2012/2013

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

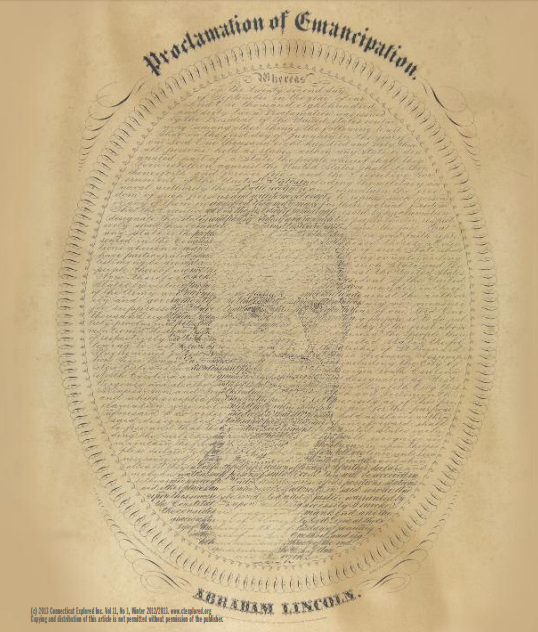

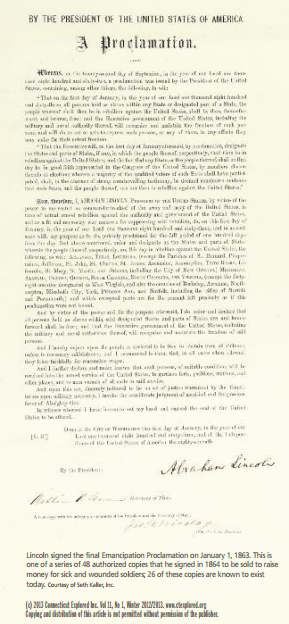

On January 1, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln instituted a revolutionary change in the nation’s history by signing the Emancipation Proclamation. In addition to freeing enslaved people in the states that were in open rebellion, the Proclamation opened the door for Black men to serve in the military. Although Lincoln had issued the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation months earlier, many questioned whether emancipation would become a reality. It created division throughout the North, causing many War Democrats who had previously tried to work with the Republican administration to turn their backs, outraged over abolition and the allegedly clear avowal that the war was no longer about saving the Union. Emancipation, violations of habeas corpus, suppression of newspapers, the conscription of soldiers; all of these acts, argued Democrats, pointed to Lincoln’s despotism and the true source of destruction for the nation.

On January 1, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln instituted a revolutionary change in the nation’s history by signing the Emancipation Proclamation. In addition to freeing enslaved people in the states that were in open rebellion, the Proclamation opened the door for Black men to serve in the military. Although Lincoln had issued the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation months earlier, many questioned whether emancipation would become a reality. It created division throughout the North, causing many War Democrats who had previously tried to work with the Republican administration to turn their backs, outraged over abolition and the allegedly clear avowal that the war was no longer about saving the Union. Emancipation, violations of habeas corpus, suppression of newspapers, the conscription of soldiers; all of these acts, argued Democrats, pointed to Lincoln’s despotism and the true source of destruction for the nation.

Free Black people in Connecticut greeted news of the Emancipation Proclamation with excitement. In New Haven, a huge celebration was held at the Temple Street Church. So many people arrived that the church could not fit the entire crowd. When this same congregation had heard of the emancipation of the enslaved in the nation’s capital in April 1862, Amos Beman had addressed an excited crowd. As Dave E. Swift notes in Black Prophets of Justice: Activist Clergy before the Civil War (Louisiana State University Press, 1989), the New Haven Palladium reported on April 22 that the earlier gathering was “probably the largest and most spirited meeting ever held in the State of Connecticut.” Now, nine months later, the Palladium announced, “That class of our citizens of whom a certain judge [Chief Justice Roger Taney] once extra-judicially decided that ‘they have no rights that white men are bound to respect,’ held a jubilee…. The platform, desk, and surroundings, were handsomely draped with American flags.” The celebration was a long time in coming. Previously, black abolitionists such as Amos Beman and James Pennington had advocated celebrating the “Negro Fourth of July,” British West Indian Emancipation, on August 1, and boycotting America’s July 4th celebrations.

Nor were Black Connecticut residents alone in recognizing President Lincoln’s Proclamation. In Norwich, Mayor James Lloyd Greene ordered on January 2 the raising of the town flag, the tolling of church bells, and a 100-gun salute [See “When Norwich Celebrated the Emancipation Proclamation“, Winter 2012/2013]. Not all, however, went well. When the mayor later presented to the common council the $98 bill for the celebration, several town residents filed for and received an injunction from the Superior Court in New London. The Norwich Aurora favored the court action and insisted that the mayor had violated the city’s charter and “the feelings of three-fourths of our tax-payers.” The Norwich Morning Bulletin opposed the injunction and concluded that “the whole movement was undoubtedly gotten up for political effect in the coming State and City elections,” and that “the movers in this matter have placed themselves in a very foolish and contemptible position.”

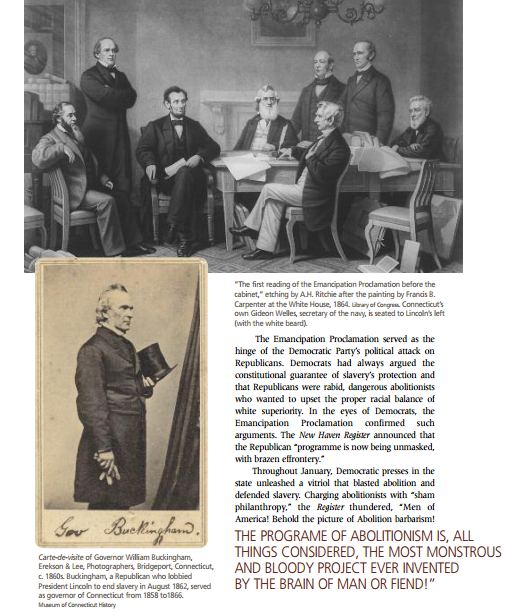

Reactions among Connecticut’s whites reflected a larger division in Connecticut over the war and the issue of slavery. Before the Civil War, Democrats and most Republicans in Connecticut had recognized the Constitution’s protection of slavery, but soon after hostilities began and the South seceded from the Union, many in the new Republican Party questioned the sanctity of that protection. Republican Governor William Buckingham’s May 1862 message to the General Assembly following his reelection made this exact point. “Slavery has forced us into a civil war,” proclaimed the governor, “but insists that we have no right to use the war power against her interest. Slavery has repudiated her obligations to the Constitution; and yet claims protection by virtue of its provisions. …He who refuses to obey its requirements, must not expect its benefits.”

For other Republicans, dismantling slavery was justified by more practical considerations. Slave labor was a distinct wartime asset for the Confederacy. Should not the Union reduce the enemy’s ability to fight by every means possible, including abolition of slavery? In August, the governor traveled to Washington with a delegation to deliver an emancipation petition to President Lincoln. Lincoln issued the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation the following month.

The Emancipation Proclamation served as the hinge of the Democratic Party’s political attack on Republicans. Democrats had always argued the constitutional guarantee of slavery’s protection and that Republicans were rabid, dangerous abolitionists who wanted to upset the proper racial balance of white superiority. In the eyes of Democrats, the Emancipation Proclamation confirmed such arguments. The New Haven Register announced that the Republican “programme is now being unmasked, with brazen effrontery.”

Throughout January, Democratic presses in the state unleashed a vitriol that blasted abolition and defended slavery. Charging abolitionists with “sham philanthropy,” the Register thundered, “Men of America! Behold the picture of Abolition barbarism! THE PROGRAME OF ABOLITIONISM IS, ALL THINGS CONSIDERED, THE MOST MONSTROUS AND BLOODY PROJECT EVER INVENTED BY THE BRAIN OF MAN OR FIEND!” The Hartford Times accused Lincoln of violating his oath of office to defend the Constitution and asserted that Republicans had now “openly proclaimed” the war “is a John Brown raid on a gigantic scale.”

In making such arguments, Democrats appealed to their loyal base, those who had always been opposed to abolition and Republicans. Yet Democrats also cast a wider net in an attempt to aggravate the underlying racism that was as ubiquitous as the stone walls that dotted Connecticut’s landscape and that Republicans had so markedly revealed when making their earlier arguments for war on the grounds of free soil and white rights.

Democrats refocused the race issue by attacking the Emancipation Proclamation’s announcement of mustering black troops. Commenting on the fact that blacks would serve under white officers, the New Haven Register announced “what everybody knows to be the case, socially and politically, at home, that the negro race are unfit associates for the officers, who are to be white men; and it also declares the insulting outrage, that these negroes, unfit as they are for the companionship of officers, are just fit for the associates and fellow soldiers of the rank and file of our gallant and patriotic army. The Representatives who thus voted for the equality of the negroes with the rank and file, were sent to represent a people who at home do not admit the negro to either social or political equality.”

The Hartford Times expressed equal exasperation: “A negro army! To fight the battles of this once mighty Nation! If anything remained that could humiliate us still more before the world, these ‘Architects of Ruin,’ now in power, have surely found it, in this measure. The project is a very degrading one. It is a confession of weakness.” It is for the purpose of calling “an inferior race to do for us what we are unable or unwilling to do for ourselves!” The paper continued in a subsequent article: “The measure is demoralizing to the army, as well as humiliating to the Union” and “this whole scheme of negro soldiers, will fall, as the emancipation proclamation must inevitably fall, after doing much more harm than good.” Needless to say, Connecticut’s 29th and 30th Colored Regiments, authorized by the General Assembly in late 1863, proved their critics wrong (see “The 29th Regiment Colored Volunteers,” Spring 2011).

The Republican press, of course, responded to Lincoln’s Proclamation with a markedly different outlook, one that rubbed hard against its previous racism and much-argued indifference to black rights, all of which it had espoused, at times viciously, during the Free Soil 1850s. In a lengthy article on January 2, the day after Emancipation, the Hartford Courant proclaimed, “now, for the first time in its history, the Government stands unequivocally committed to the support of the fundamental principles on which it was originally founded. Hitherto our national life has been disfigured by a glaring inconsistency. To justify the revolution which established our independence, we proclaimed our belief in certain inalienable rights as common to all men; to subserve the ends of self-interest we have suffered a sixth part of the population of the land to groan under despotism that repudiates every liberal maxim, and is still upheld by the gravest sanction of constitution and law. Nowhere else has such an anomaly in government ever existed. Here it exists no longer.”

The Republican press, of course, responded to Lincoln’s Proclamation with a markedly different outlook, one that rubbed hard against its previous racism and much-argued indifference to black rights, all of which it had espoused, at times viciously, during the Free Soil 1850s. In a lengthy article on January 2, the day after Emancipation, the Hartford Courant proclaimed, “now, for the first time in its history, the Government stands unequivocally committed to the support of the fundamental principles on which it was originally founded. Hitherto our national life has been disfigured by a glaring inconsistency. To justify the revolution which established our independence, we proclaimed our belief in certain inalienable rights as common to all men; to subserve the ends of self-interest we have suffered a sixth part of the population of the land to groan under despotism that repudiates every liberal maxim, and is still upheld by the gravest sanction of constitution and law. Nowhere else has such an anomaly in government ever existed. Here it exists no longer.”

Although the Courant accurately captured the inherent paradox of accepting slavery at the nation’s founding, it failed to adequately explore those very inconsistencies, suggesting instead that Jefferson and the Founders had presumably included blacks as recipients of the Declaration’s promises. Nor did the paper confront the equally challenging problem of slavery’s constitutional sanction. Still, recognizing that some in Connecticut might cringe at the idea of black equality, the Courant theorized that no immediate, radical changes would take place: “Centuries of degradation debase the qualities of manhood. Races do not spring at a bound from the lowest plane of humanity to a participation in the pride, and hopes, and thirsts which grow up with civilization. We incline strongly to the belief that the negro himself, will remain passive.”

Months later, at the end of March, the Courant published another article championing freedom. Once again, it paid no heed to its previous antagonism towards blacks, and thus began the creation of a mythic moral North versus an oppressive South: “We are now passing through a crisis which is to affect materially the destiny of the race. Two antagonistic systems have joined in mortal combat. On the one side, is liberty supported by the maxims of philosophy and the truths of religion; on the other, an enormous system of oppression that drags the only apologies for its existence from the rubbish of past ages and long exploded theories.” The paper continued, however paradoxically, that, “America is the home of freedom. Our Government is based upon an acknowledgement of the fundamental and absolute equality of man.” As the Courant continued with its racial amnesia, it at least acknowledged the difficulties of the Constitution’s protection of slavery. “Practically we have denied what theoretically we claimed to be a self-evident truth. Had the supporters of human slavery observed the obligations of the Constitution, this strange anomaly might have continued for many years to come.” The only way around the Union’s foundational document, explained the Courant, was for the South to choose war. “They put themselves without the pale and protection of the Constitution,” and “that crime sealed the death warrant of bondage in America.”

In April, the Courant one again addressed the issue of the North’s moral opposition to slavery by raising William H. Seward’s famous 1858 irrepressible conflict speech in Rochester, New York, in which he argued that the march toward abolition was unstoppable. Connecticut, of course, and the Courant, too, had never embraced such arguments, but by 1863 the paper announced that “the idea of freedom in the northern mind had become irrepressible,” and “the North would have sinned against their deepest convictions in permitting slavery to encroach further upon the domains of freedom.” The nurturing of a vast, mythic, Northern moral crusade against slavery was in full march.

This article is adapted from Warshauer’s Connecticut in the American Civil War: Slavery, Sacrifice, & Survival (Wesleyan University Press, 2011). Warshauer is professor of history at Central Connecticut State University and chairs Connecticut Explored’s editorial board.

Explore!

Read more about the Emancipation Proclamation in Connecticut in our Winter 2012/2013 issue.

Read more about Connecticut in the Civil War on our TOPICS page.