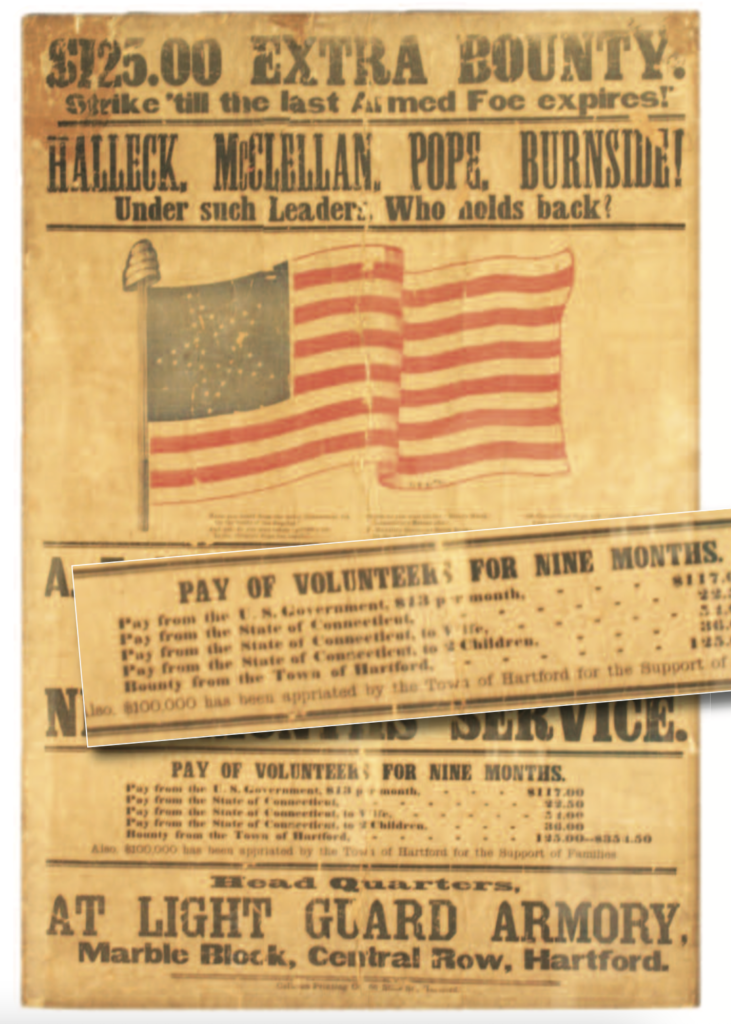

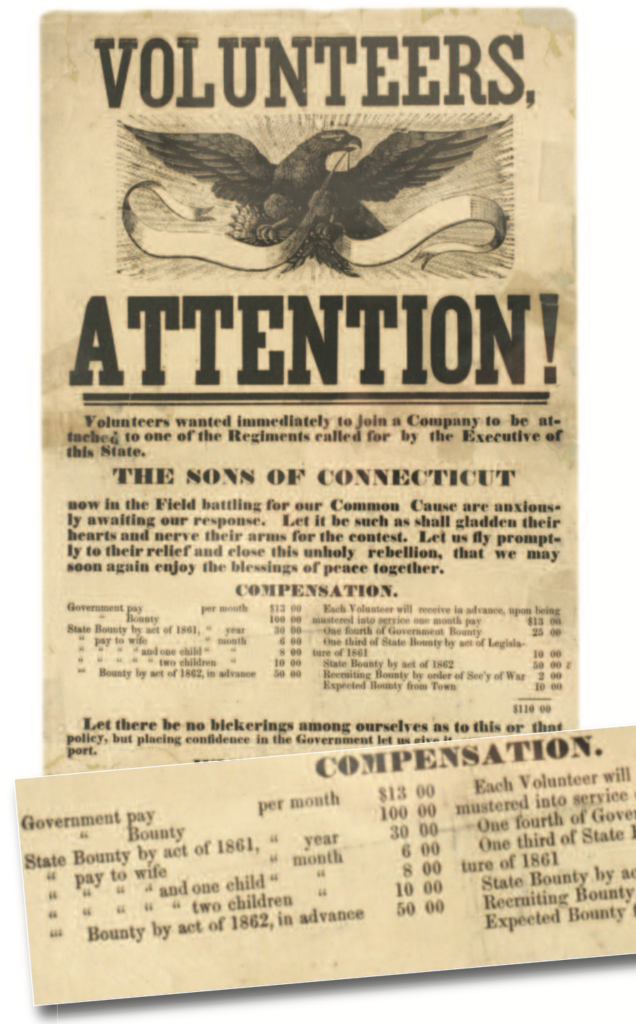

Connecticut initially raised three regiments for nine months’ service, thinking it would be a short war. This recruiting poster from 1861 lists the compensation offered at the start of the war: a combination of U.S. pay, state bounty, and Hartford bounty. Museum of Connecticut History

By James E. Brown

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Winter 2014/2015

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

When William Buckingham was sworn in as governor of Connecticut on the first Wednesday in May 1858, he would have had no reason to predict that his biographers would someday refer to him as “Connecticut’s War Governor” and “Connecticut’s Lincoln.” At that time, Connecticut was recovering from the economic panic of 1857, and Buckingham had been chosen by the relatively new Republican Party as its candidate for governor—an election he would win over the Democratic Party’s candidate, former Connecticut Congressman James T. Pratt. Buckingham would go on to win the following seven annual gubernatorial elections, too. Three years after Buckingham first became governor, the Civil War would thrust him, and Connecticut, into the thick of the political conflict, even as more than 55,000 Connecticut soldiers joined the military battle.

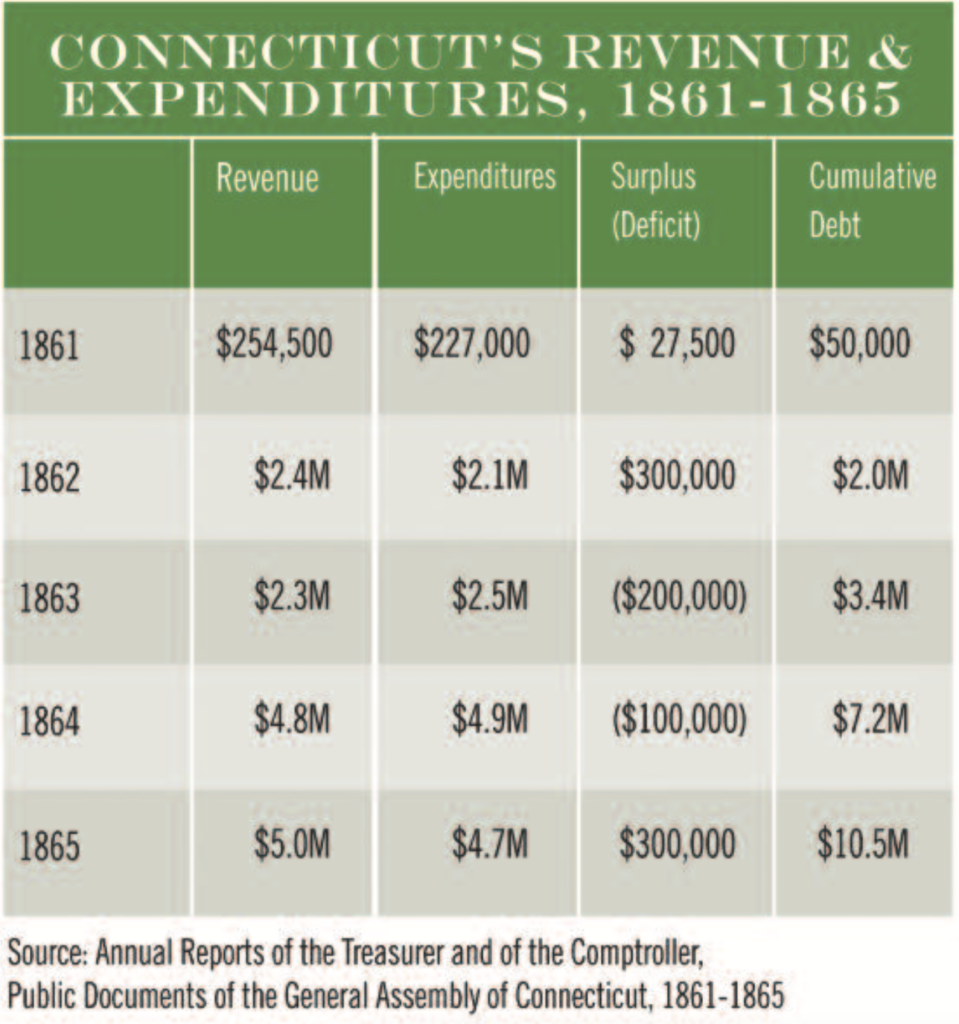

In considering the factors that contributed to the Union’s ultimate victory in the Civil War, we typically focus first on the battles, the military strategy, the loss of life and limb, and the sacrifices by families and friends on the home front. But the military outcome was also necessarily affected by the strengths and weaknesses of the financial resources and strategies of the North and the South. In this regard, Governor Buckingham and other Connecticut officials faced many of the same public policy issues that President Abraham Lincoln and Congress faced at the national level: how to identify and gather resources, whether to pay for those resources by raising taxes, by borrowing, or by some other means, how to balance the competing interests of individuals, farmers, and small businesses on the one hand, and the state’s corporations on the other, and how to do all of this in such a way as to minimize conflict and dissention and assure broad-based support for the war effort. And consider this: in the fiscal year ending March 31, 1861, before the start of the war, total expenditures from Connecticut’s general fund came to $220,000. By the end of the war, Connecticut had expended more than $20 million, including more than $5 million spent by Connecticut towns. By March 1865, the state’s annual revenue and expenses each amounted to approximately $5 million; the state debt, which had been $50,000 in 1861, had risen to a whopping $10.5 million.

Federal Financing Strategies

To fully appreciate the challenge that Buckingham and state legislators faced, it’s important to remember how the federal government operated in that era, and particularly to consider the disconnect between governmental and commercial business. While the private economy had grown substantially in size and complexity during the 1850s, this growth was decidedly not mirrored in the federal government. In the mid-1800s, money flowed through the economy very slowly. There were no federal banks, no centralized banking process, and no national currency system. Though any commercial business could borrow from a bank, by self-imposed rules the federal government could not. In fact, the government had intentionally avoided ongoing business interactions with banks for two decades. The government conducted its financial business only in gold and silver. Private banking was conducted by more than 1,600 state banks, and transactions across the nation involved more than 7,000 different kinds of bank notes.

The Union had clear advantages going into the war. It had the majority of the population and of the national income and also had a diverse economy. Ironically, however, the Union could only win the war if the conflict lasted long enough for the federal government to benefit from these advantages. It needed to establish a financial infrastructure flexible enough to take in large amounts of revenue and to make unprecedented war-time expenditures efficiently and on a timely basis.

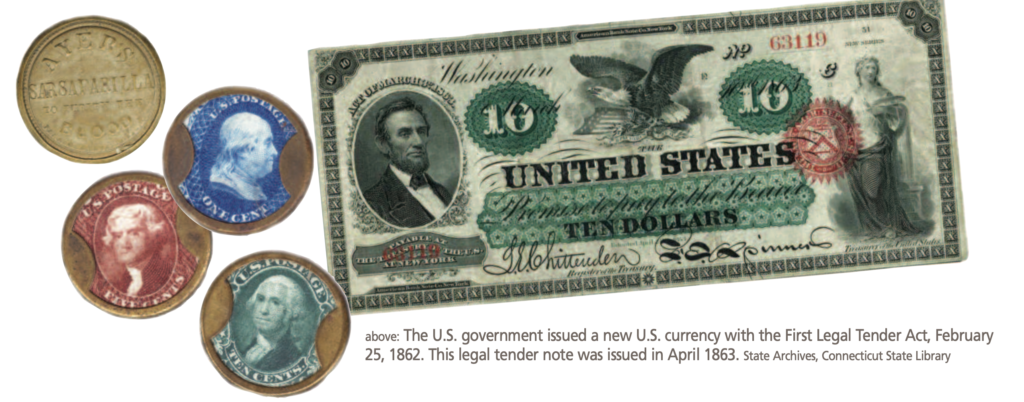

The U.S. government issued a new U.S. currency with the First Legal Tender Act, February 25, 1862. This legal tender note was issued in April 1863. State Archives, Connecticut State Library

Before 1861, the federal government obtained its revenue almost exclusively from tariffs, or custom duties, and from the proceeds from the sale of public land. There was no federal system of taxation of individuals and businesses with respect to activities occurring within the United States, and there was no meaningful taxation infrastructure. Moreover, borrowing as a source of revenue was slow and difficult, as virtually every detail had to be approved by Congress.

Mistakenly assuming that the war would be of short duration, the Lincoln administration went into the conflict with a revenue-raising philosophy that emphasized borrowing over imposing taxes or issuing new money. There was a clear political element to this strategy. Some banks and other financial institutions had argued against raising taxes substantially because they believed that the war would be of short duration and because they feared that higher taxes would turn public sentiment against the war.

Congress met in special session in July 1861. Treasury Secretary Salmon Chase proposed that estimated expenditures of $318 million for the year be funded with $80 million in taxes and $240 million in borrowing. Congress acted on Chase’s advice and authorized him to borrow up to $250 million. Congress also passed a related revenue bill that included a tax on real estate, a 3 percent tax on personal income greater than $600 per year, and higher tariffs.

In January 1862 The New York Times made an impassioned plea for fiscal responsibility: “Hitherto taxation has been so light in this favored land, that our people have not yet learned the lesson long patent to every other on earth. But we must come to it, and that speedily. Liberal taxation is the only sound basis we can offer for the vast loans that will be needed to carry our existing war to a successful conclusion.” In July 1862, Congress enacted a complex tax bill with a progressive tilt: it imposed higher rates of taxation on higher incomes.

As a practical matter, because of the time delay involved in collecting the income tax and also because of credits for war expenditures allowed against the property tax, neither proved to be a meaningful source of revenue during the war. The income tax provided no revenue in 1861 or 1862 and less than $3 million in 1863, before growing to $20.3 million in 1864 and $61 million in 1865. The direct tax on property raised only $1.8 million in 1862 and even less in subsequent years. But whereas taxes accounted for only 10 percent of revenue in 1862, they accounted for 25 percent in 1864 and 1865.

Still, over the course of the war borrowing was the predominant strategy, effected through marketing bonds. During the war years, the federal government collected just over $800 million in taxes, while borrowing $2.6 billion through bonds. And despite the creation of taxes on items sold or activities occurring within the U.S., the bulk of tax revenue throughout the war years continued to come from tariffs or customs duties on foreign goods.

On the expense side, war-related expenditures clearly dominated federal spending, while other government spending and spending on foreign affairs did not grow significantly, particularly during the early years of the war. Of course, the focus on borrowing to fund the war meant interest expense grew continuously. In fact, interest expense alone in the fiscal year that ended on March 31, 1865 exceeded the entire federal budget for the fiscal year that ended on March 31, 1961!

Not surprisingly, the federal budget experienced “financial embarrassment” in the form of deficits in every year during the war. Except in 1864, the deficit each year exceeded the deficit from the preceding year, growing in the aggregate from $75 million in 1860 to $2.7 billion at the end of the war. The federal debt peaked at $2.75 billion in 1866.

A tangential but nevertheless interesting issue relates to the use, and then the non-use, of gold and silver in financial transactions during the war years. As war-related expenses were growing at an unprecedented rate, commercial banks and the federal government became concerned that paying out gold and silver in redemption of banknotes would deplete their supplies. In the fall 1861 and into 1862, private banks stopped making such payments, and shortly thereafter the federal government did the same. One result, in Connecticut and in other states, was the disappearance of coins, which people began hoarding. This seriously inconvenienced retail trade. To address the shortage of coins, people simply cut dollar bills into halves or quarters and using them as currency wherever they might be accepted. In Hartford, for example, some $20,000 of the bills of the Aetna Bank that had been cut in two were in circulation in 1862, according to Wesley C. Mitchell’s 1902 article “The Circulating Medium During the Civil War” (Journal of Political Economy, 10 no. 4). This informal creation of currency was followed by Congress’s authorization for the use of stamps as currency and for the issuance of fractional currency or “paper coins” in denominations as low as 3, 5, and 10 cents. This was the only way to transact in amounts less than $1.

Connecticut’s Political Landscape

With the exception of the option to print money, virtually all of the financing issues that arose in Washington during the Civil War had to be addressed in Hartford and New Haven as well. (Until 1875, Connecticut had two capitals; sessions of the Connecticut General Assembly met alternately in Hartford and New Haven.)The political context in which those issues were debated in Connecticut is enlightening.

Buckingham, a native of Norwich, had previously only been involved in local politics. Both the absence of political baggage and his reputation as a respected and successful businessman attracted voters to Buckingham in the election of 1858.

State of Connecticut recruiting poster, Meriden, July 10, 1862, showing (inset) compensation offered to recruits in 1862. State Archives, Connecticut State Library

As he led Connecticut through the thicket of decisions forced by the war, Buckingham proved to be the right man at the right time for the job. He mobilized and motivated the citizenry, coordinated with leadership in the legislature on important fiscal and non-fiscal policy decisions, traveled frequently to Washington and communicated directly with President Lincoln, and demonstrated concern and compassion for Connecticut troops.

Buckingham’s popularity and success during the war years contrasted with the status of the state’s Democrats, whose antebellum disputes on a national level were replicated in Connecticut and contributed to weakening the Democratic Party throughout the war. Democrats were viewed as falling into one of two camps: the “Peace Democrats” or the “Union Democrats.” The latter were also known as the “War Democrats.” Peace Democrats were nostalgic for an idealized Southern society and were strongly Jeffersonian in their politics. They saw no need for the war and feared that Northern victory would result in trampling of individual liberties and states’ rights and the imposition of an intrusive federal government.

The Union, or War, Democrats, generally but not aggressively supported the war effort once it became apparent that conflict could not be avoided and was underway. Nevertheless, they opposed many of the policies of the Lincoln administration, including the Emancipation Proclamation, conscription, suspensions of the writ of habeas corpus, and wartime taxes.

Connecticut’s Financing Strategies

The day after President Lincoln issued his first call for troops following the capture of Fort Sumter in April 1861, Governor Buckingham called for volunteers to form a regiment in Hartford; the next day he issued a similar call in New Haven. Financing Connecticut’s participation in the coming war was an immediate concern. The general assembly was not in session, and no funds were available for war expenditures, so Buckingham applied for a $50,000 loan from the Thames Bank of Norwich. Within days, numerous other banks offered to lend funds to the state, and in short order the governor had more than $1 million at his disposal. As he took advantage of these offers, the governor gave the banks a document that read:

Sir – This will be presented by _______ through whom I propose to avail myself of your patriotic offer of money to aid the State amid the present national calamities. Honor such drafts as he may draw on you and charge the same to the State, for the final payment of which I hold myself personally responsible.”

The state thus borrowed substantially at the beginning of the conflict, and in the initial absence of legislative authorization, Buckingham provided the banks with his own personal security.

When the general assembly met the following month, Buckingham asked legislators to address the state’s needs on a timely basis. Among other things, the first law enacted during the May 1861 legislative session appropriated $2 million for war expenditures and authorized the state treasurer to borrow funds by issuing bonds to defray these expenses.

In October 1861, after President Lincoln had called for 500,000 troops, of which Connecticut’s quota was 12,000, the general assembly appropriated another $2 million and authorized the state treasurer to issue bonds of up to that amount. The towns also began soliciting volunteers for military service and raising funds to pay them and to assist their families. In Enfield and Waterbury, $10,000 was raised; in Woodbury $5,000 in family aid was collected. Similar activity occurred in Coventry, Middletown, Stafford, West Hartford, and elsewhere.

By May 1862, Connecticut had contributed 13,500 troops, expended more than $1.5 million, and secured from the federal government an I.O.U. in the amount of $600,000. In July, the general assembly enacted legislation addressing taxation for the first time during the war.

The Connecticut General Assembly continued to authorize borrowing throughout the rest of the war: $2 million in May 1862, January 1863, and May 1863, and $3 million in May 1865. In his 1865 message to the assembly, Governor Buckingham addressed the substantial borrowing but expressed optimism about Connecticut’s ability to pay off these obligations. He noted that the grand list had seen a meaningful increase during the year; this reflected continuing growth in Connecticut businesses, both in war-related industries (e.g., arms manufacturing, ship-building, and textiles) and in other industries as well (e.g., banking and insurance). Buckingham reported that the total amount of Connecticut’s debt was less than two-thirds of that annual increased value and less than 4.25 percent of the value of the grand list. In addition, Connecticut was eventually able to recover more than $2 million in war claims from the federal government.

Connecticut’s revenues, expenditures, surplus/deficit, and cumulative deficit during the course of the war (Table 1) show a dramatic rise in the size of the budget between 1861 and 1862, with revenues increasing more than 10-fold. Approximately $2 million of the revenue in 1862 came from the sale of state bonds. In the same period, expenditures increased at a similar rate, from $227,000 to $2.1 million. More than $1.5 million in 1862 went to bounty payments to soldiers, payments to soldiers’ families, and the purchase of equipment, supplies, and food for the troops. As noted above, by March 1865, annual expenditures were approximately $5 million and the state debt had mounted to $10.5 million.

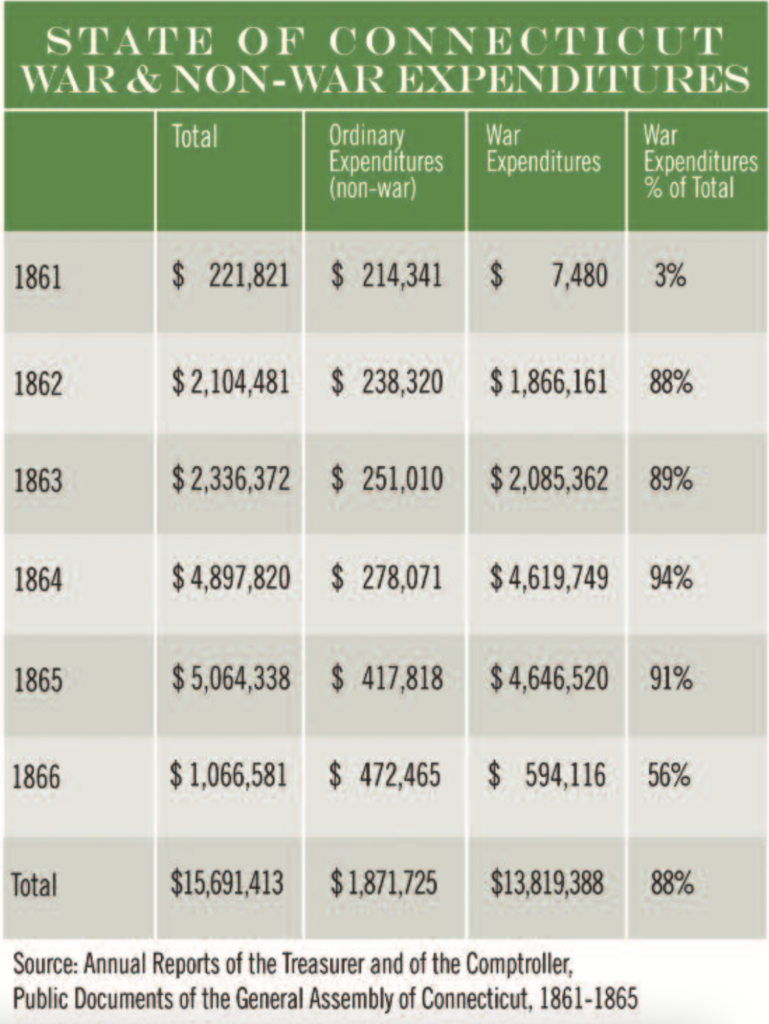

War-related expenditures accounted for 90 percent of the state budget each year from 1862 through the end of the war (Table 2). Non-war-related, i.e., “normal” state expenditures grew modestly from 1861 through 1864; they grew substantially in 1865, reflecting increased revenues from taxes in 1864 and 1865.

Long-Term Impact

William Buckingham’s business experience proved invaluable to his political leadership during the Civil War. For example, it was Buckingham’s idea to shift the proceeds from the sale of Connecticut bonds directly to the U.S. Treasury, thus providing the Lincoln administration not only with desperately needed financial assistance but also the benefit of Connecticut’s superior credit position. With the war over in 1865, Buckingham decided that being elected governor eight times was enough. His return to business was short-lived, though, as it was interrupted by his election as U.S. Senator from Connecticut, which position he held until his death in 1875.

At the national level, changes that continue to affect us today—the initiation of a federal income tax, the establishment of an internal revenue bureau (now the IRS), the adoption of a national banking system and a national currency—all can be said to have been realized only because of needs imposed by the Civil War. The much larger and farther-reaching role of the federal government that arose out of necessity during the war continued to grow after the fighting was over. The disconnect between governmental and commercial business had disappeared forever.

In Connecticut, able leadership rose to the occasion, motivated Connecticut’s citizens, and adopted financial strategies that reasonably balanced the interests of varied constituencies. And when the war ended, Connecticut’s government was poised to respond to a diverse and rapidly evolving economy.

James E. Brown is a corporate attorney. This article is adapted from a longer essay in Inside Connecticut and the Civil War: Essays on One State’s Struggles (Wesleyan University Press, 2014).

Explore!

Read all of our stories about Connecticut in the Civil War on our TOPICS page