By Dean E. Nelson

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Spring 2011

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

A year into the Civil War, the U.S. War Department’s “Commission on Ordnance and Ordnance Stores” reported to Congress on the state of the nation’s confused armament contracts involving tens of millions of federal dollars. The goal was to impose order on the frenzied rush to arm the Union caused by “the unexampled demand for arms consequent upon the sudden breaking out of the present gigantic rebellion….” In the report, General James W. Ripley, chief of ordnance, estimated 500,000 new Model Springfield .58-caliber rifle muskets (“the best infantry arm in the world”) would be needed in the next 12 months; he also assessed how many rifles and revolvers would be needed. Connecticut’s armories were ready to respond.

By the mid 19th century, Connecticut manufacturers had mastered the complexities of innovation, capital, labor, and raw materials for machine-based precision mass production of intricate metal parts and, with a collective and deeply rooted firearms production heritage going back a half century, were ideally poised to make arms for the Union. By the war’s end, Connecticut makers had supplied some 43 percent of the grand total of all rifle muskets, breech loading rifles and carbines, and revolvers bought by the War Department, along with staggering quantities of small arms and artillery ammunition.

Rifles and Carbines

Of 23 private Northern contractors rising to the challenge and pursuit of profit in Model 1861 Springfield rifle musket manufacture, 8 Connecticut entrepreneurs and established gun-makers together delivered an extraordinary 37 percent of the war’s-end rifle contract total: more than 155,000 regulation guns plus 75,000 Colt Special Model 1861 rifle muskets to supplement the National Armory output at Springfield.

Connecticut’s major rifle makers included Colt Patent Firearms Manufacturing Company of Hartford. As the war broke in the spring of 1861, Colt was coincidentally well into design and development of its newest military shoulder arm, its first muzzle-loader (loaded at the muzzle end of the barrel). It was generally similar to the government Model 1861s, but not cross-interchangable in lock, stock, or barrel. The War Department waived its requirement of parts compatibility and contracted for these non-conforming guns in part because General Ripley, in the commission report, endorsed Colt as “probably further advanced in their preparations than any of the other companies…we are more likely to get good home manufactured arms from them…. in less time than elsewhere…”

The Ordnance Commission report cited two other Connecticut private armories, Whitney Arms Company in New Haven and Savage Revolving Firearms Company in Middletown, as well established. But other Connecticut firms without gun-making experience moved into rifle production, too. For these newcomers, musket production posed an industrial challenge. Before the war, Parker Snow & Company of Meriden made kitchen utensils and sewing machines; the Connecticut Arms Company of Norfolk forged wagon axles; William Muir, a New York dry goods merchant who started his new gun making company in Windsor Locks; and the triumvirate of J. D. Mowery, Norwich Arms, and Eagleville Manufacturing Company, all of Norwich, who were principally textile manufacturers.

The Model 1861 rifle musket and its close cousin the Colt 1861 Special Model were the finest infantry shoulder arms issued to rank and file and the most common Union infantry arm of the war. Muzzle loading, single-shot, and sighted to five hundred yards, they fired a one-ounce lead conical-shape hollow base bullet propelled by 65 grains (a weight avoirdupois) of gun powder with average velocity of an astonishing 1,000 feet per second. The 58/100-inch (.58 caliber) bore was rifled with three slow spiral grooves that imparted to the bullet an axial spin that stabilized and ensured a true, speedy flight. Resolute infantrymen could load and fire one aimed shot about every 30 seconds, and average shooters could routinely hit a five-foot-square target at 100 yards. Bullet strikes to the head, chest, and stomach were generally death blows.

Gearing up to produce such arms required extensive retooling. The machinery inventory of any armory making most of their own major parts would count steam engines, boilers and piping to run an arrayed sequence of reamers, lathes, milling machines, grinding machines, planers, drill presses, polishing frames, screw machines, drop presses, trip hammers, belting, shafting, heat treating furnaces, and more. Mark Twain, a special correspondent for the San Francisco newspaper Alta California, in 1868 described Colt’s complex operation (albeit the factory’s post-war, 1864-fire rebuild): “…on every floor is a dense wilderness of strange iron machines… a tangled forest of rods, bars, pulleys, wheels, and all the imaginable and unimaginable forms of mechanism. …machines that shave [parts]down neatly to a proper size, as deftly as one would shave a candle in a lathe…” Some companies sidestepped the challenge: Connecticut Arms Company and William Muir & Company, for instance, opted to assemble arms with parts made by sub-contractors and therefore required little more than workbenches and simple hand tools to adapt to its new line of production.

The interchangeability of each and every component part, regardless of maker, was a War Department requirement. To that end, the Union’s 1862 Ordnance Manual listed 77 distinct “verifying gauges” for the 50 parts of a rifle musket and specified that “Each component part is first inspected by itself and afterwards the arm in a finished state.” At the discretion of the government inspector, completed arms were priced according to quality of fit and finish in four classes. The government paid a high of $20 for a first-class Model 1861 rifle musket and $16 for one deemed fourth class. Whitney posited in ordnance hearings that his profit per gun might be around $3, or 15 percent.

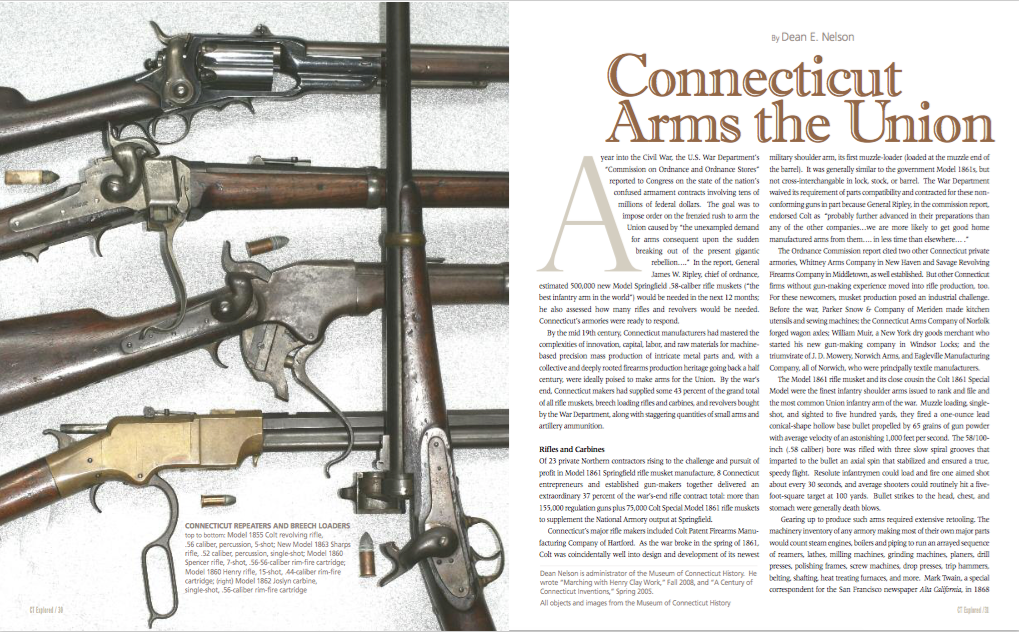

The Sharps Rifle Company of Hartford was well respected by the government before the war for its reliable single-shot percussion .52-caliber breech loading (loaded at the rear of the barrel) carbines (a lighter rifle with a shorter barrel) and rifles. General Ripley implored of Sharps late in 1861: “…. I desire that you will continue to supply this department with Sharp’s carbines, to the utmost capacity of your factory, until further orders.” Sharps’s carbines were by far the most common Union cavalry arms of the war. Their rifles, most set up for angular bayonets, armed the famed Berdan’s Sharpshooters with limited quantities issued to 10 Connecticut regiments, especially flank companies and for arming picked marksmen. With $2,400,100 in War Department sales, Sharps ranked fifth in the nation of the 13 military contractors that surpassed $1 million in government sales.

Connecticut inventors secured 70 patents for arms and munitions between 1840 and 1865. The introduction of Manchester, Connecticut, inventor Christopher M. Spencer’s 1860 ingenious patent repeating rifle and carbine into U.S. service benefited substantially from his contacts with Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles of Glastonbury, who got him an initial contract for 800, though at the time “the only things they lacked were a factory, machinery, and a workforce.” Securing financial backing in Boston, Spencer scrambled to establish his armory in the Chickering Piano factory in Boston, and through political connections, even arranged a presidential test fire with Abraham Lincoln on the White House grounds. The Spencer made use of coil springs for butt-stock magazine feeding of newly perfected rim-fire metallic cartridges, which held lead bullet, explosive powder charge, and detonating primer all fixed in a copper casing. A soldier observed, “The 37th [Massachusetts Volunteers] have now the Spencer Repeating Rifle, which can be discharged eight times with but two or three seconds intermission, and then eight more charges can be put in the magazine of the gun more quickly than you can put one charge in the Springfield Rifle…. Having this rifle carries this disadvantage:… any delicate and difficult job to be done…is almost sure to bring into requisition our regt…” The Spencer carbine was the second most common Union cavalry shoulder arm. The army purchased 11,471 rifles with angular bayonets. Spencer Arms Company finished the war with the eighth highest contract total, at $2,078,427.

Inventor Benjamin Tyler Henry worked tirelessly for Oliver Winchester’s New Haven Arms Company to get his 1860 patented .44-caliber repeating rifle (nicknamed a “Henry”) into mass production. It, like the Spencer, employed a coil spring to feed rim-fire bullets into the loading mechanism. The Henry failed to attract much interest from the U.S. government—because it lacked the range and stopping power of other military shoulder arms—until the last year of the war’s purchase of only 1,200, which represented about 10 percent of total production. In the Ordnance Commission report, General Ripley balked at the rifles’ “…lack of practical trials…as military weapons…” their weight and need for special ammunition and “…very high prices asked…” Soldiers liked it, though. A soldier of the 1st District of Columbia Cavalry wrote: “We have got our rifles and they are a nice pretty piece…we can fire fifteen rounds without loading…The rebs say that we can load up on Sunday and fire all week…the rebs hate them sixteen shooters worse than they do the verry [sic]devil himself.”

The models 1862 and 1864 carbines of Benjamin Joslyn’s Firearms Company in Stonington were single-shot breechloaders using .56-caliber rim-fire metallic cartridges. West Point trials documented the firing of 40 shots in five minutes. Connecticut manufacturers of breech loaders and repeaters (perhaps a bit generously including Christopher Spencer’s Boston operation) can be credited with 47 percent of those arms genres totals.

Revolvers

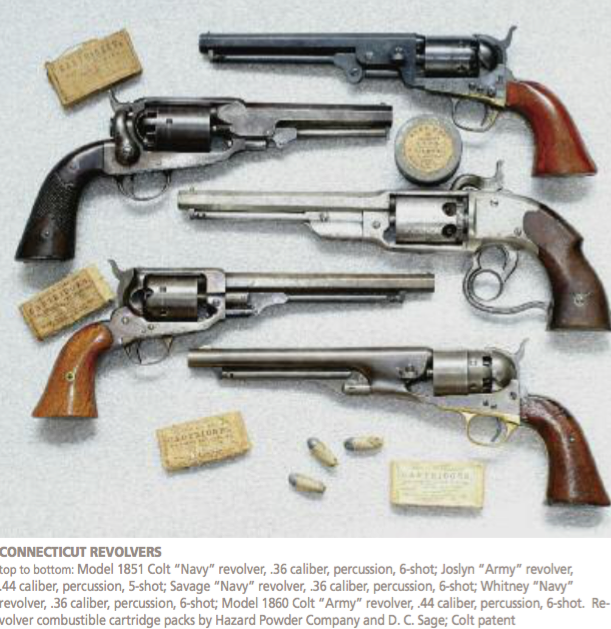

Connecticut’s claim to have produced 47 percent of all the domestically made percussion military revolvers used by Union forces is no stretch. The Ordnance Department in September 1861 requested of Colt’s: “Deliver weekly, until further orders, as many of your pistols, holsters, new pattern, as you can make.” Those Model 1860 Army .44-caliber percussion revolvers, priced initially at $25 each (reduced to $14.50 in the spring of 1862 to be competitively priced with rival Illion, New York, Remington Army revolvers), saw regular deliveries in lots of 1,000 or more per week through November 1864 until the pistol works burned in February 1864, ending revolver production for the remainder of the war. Colt sold more revolvers to the Ordnance Department than any other maker. Colt’s revolvers orders combined with its Special Model rifle musket orders totaled $4,687,031, the second-greatest Union armament contracts total for the war.

Like Colt, three other Connecticut military shoulder arms makers had contracts for revolvers as well. Savage Repeating Arms Company, Whitney Arms Company, and Joslyn Firearms Company each produced distinctive patented percussion handguns with both military purchases and commercial open market sales.

Ammunition

In addition to arms, Connecticut companies supplied great quantities of small arms ammunition, primers, and explosives. Black gun powder is a explosive propellant that when detonated converts instantaneously from solid particles into a hot gas some 400 times greater in volume than its granular form, forcing a lead bullet out of the gun in velocity from 800 to 1,100 feet per second. Percussion caps were pieces of thin sheet copper in a shape resembling a tiny top hat containing mercury fulminate that when struck exploded with hot flame flashing through to set off the powder charge in a gun’s breech chamber.

The Hazard Powder Company in the Hazardville district of Enfield, established in 1843, provided the U.S. government with quantities of black powder for Civil War artillery and small arms second only to quantities supplied by the DuPont Company of Wilmington, Delaware. But it was dangerous work. In July 23, 1863, an explosion at the Hazard Powder Company destroyed a portion of the factory. An estimated 40 tons of powder detonated, killing eight men and one woman. The magnitude of the works was such, however, that this catastrophe hardly delayed delivery of powder and fixed ammunition.

The Hartford Cartridge Works and Colt’s also manufactured cartridges. The September 11, 1861 Hartford Daily Times reported, “The Hartford Cartridge Works employ[s]from 50 to 70 hands, mostly girls, and the number of cartridges sent out for the use of the troops is enormous. Cartridges are here made not only for Colts, Savage and other revolving pistols, but for the Enfield, Minie, Sharps and other rifles.” The factory required six tons of lead and two tons of powder per week. The Ordnance Department determined, however, that Colt-made cartridges were 2 1/2 times more expensive than compatible percussion revolver ammunition made in government facilities and consequently withheld orders from Colt.

From the mid-1850s through 1864, inventor Benjamin Hotchkiss of Sharon was awarded five rifled artillery projectile patents and five patents for fuses to detonate bursting charges of his shells. Hotchkiss and Sons, their offices in New York City, cast tons of northwestern Connecticut grey iron into three major projectile types, each in several diameters and weights for different muzzle-loading cannon: solid shot for battering masonry, buildings, and naval vessels; hollow shells to burst before enemy lines with great flash and numbing concussion; and hollow shells packed with lead balls and a minimal bursting charge, termed “case shot,” to crack open and spew their deadly contents and casing into the foe. The projectiles set a lead band between the weighty iron forepart of the shot or shell and a cupped, fitted iron base. The shock of the propelling charge explosion compressed the lead band into the cannon’s rifled bore and stabilized the projectile’s flight. A battle account declared, “One of the most startling sounds is that of the Hotchkiss shell. It comes like a shriek of a demon, and the bravest old soldiers feel like ducking when they hear it… there is a great deal in mere sound to work upon our fears. The tremendous scream is caused by a ragged edge of lead which is left on the shell.”

Hotchkiss projectiles were among the three most common for Union rifled field guns. A July 5, 1863, telegram from the Ordnance Department said “Please send to the Washington arsenal 50,000 3-inch rifle projectiles…make every exertion to turn them out rapidly.” Hotchkiss’s patents also included the canister, a shotgun-like load of lead or iron balls within a tin housing secured to a cupped base of lead bearing the Hotchkiss name and patent date cast in bold relief, fired at close range. The patents gave the company a cast-iron monopoly: U.S. government sales approached $1.5 million, with projectiles each costing $1 to $2. Hotchkiss and Sons ranked tenth among the 13 Northern ordnance contractors exceeding $1 million in government sales.

Bayonets and Swords

Grounded in three decades of axe, adze, machete, plow, and agricultural implement making, Collins and Company in the Collinsville district of Canton saw the outbreak of war suddenly suspend all its Southern markets. Company owner Samuel Collins noted in his diary, “We have just commenced the manufacture of swords and bayonets to keep our men employed and expecting to get a fair profit on them.” Metaphorically beating plowshares into swords, the company drew on its considerable expertise in metallurgy, forging, drawing, grinding, sharpening, and polishing to immediately and seamlessly go into edged-weapon manufacture. Instead of vying for U.S. contracts, however, they sold swords and finished, mirror-bright, unhilted blades for custom setting-up and elaborate etching directly to prestigious retail military outfitters catering to officers; they also contracted angular bayonets and sword bayonets variously to Whitney, Sharps, Colt, and even Springfield Armory, without Ordnance Department involvement.

The Lincoln administration and Union commands in the field were able to vigorously pursue their respective political and strategic goals backed by a supreme confidence that there were armaments and munitions aplenty to press the war. Northern industrial might, with Connecticut manufacturers well in the forefront, ensured eventual military triumph on the battlefield. The end of armed hostilities and consequent surplussing of hundreds of thousands of soon-to-be-obsolete military guns predictably saw many of Connecticut’s wartime contractors withdraw from the armaments business. Collins went back to agricultural implements. Parker expanded its line of kitchen hardwares and began post-war manufacture of fine commercial shotguns. Spencer, in Boston, and Joslyn sold off their production machinery. Colt, Whitney, Sharps, and Henry (becoming in 1866 the Winchester Repeating Arms Company) adapted quickly to the new era of self-contained metallic cartridges and dominated the American firearms industry long after the war.

Dean Nelson is administrator of the Museum of Connecticut History. He wrote “Marching with Henry Clay Work,” Fall 2008, and “A Century of Connecticut Inventions,” Spring 2005.

Explore!

Read more about Connecticut in the Civil War in Spring 2011 and Winter 2012/2013 and on our Connecticut at War TOPICS page.

Read more about Connecticut made products and inventions on our Made in Connecticut TOPICS page.