by Katherine Kane

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. SUMMER 2011

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

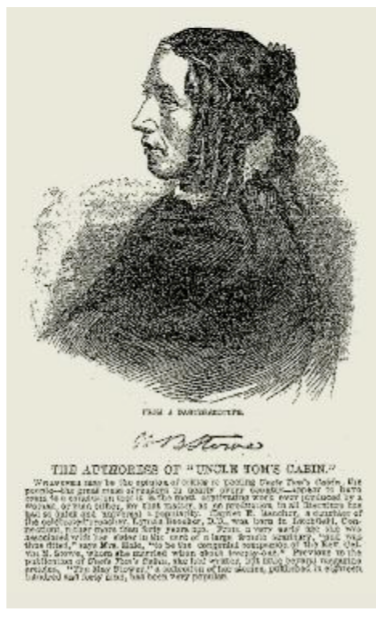

The massive crowd in Liverpool, England had been lined up at the dock for hours to get a glimpse of the famous American author. Luckily, the sky was clear after nearly a week of rain and gale winds as several hundred men, women, and children waited patiently that Sunday morning in early April 1853. Excitement mounted as the tender approached from the steamship Canada. A petite woman in her early 40s, barely five feet tall, stepped off the small boat and slowly made her way down the wharf to a carriage as admirers pushed and shoved to get a look. Some bowed their heads as she passed. Her name was Harriet Beecher Stowe, and she was internationally famous for her antislavery novel, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, published in March 1852.

A complex work exploring family and home, religion and justice, Uncle Tom’s Cabin exposed the immorality of slavery and cried for its demise. Stowe’s book, originally run as a 41-part series in an abolitionist newspaper, was a runaway success, selling 10,000 copies in a week and more than 300,000 copies in the United States in its first year, despite being widely banned in the South. It became the best-selling book of the 19th century, second only to the Bible, and galvanized the abolition movement, leading to the outbreak of the Civil War. It changed public opinion, created characters still talked about, influenced ideas about equity, and fomented revolution from Russia to Cuba.

Stowe’s goal was to “write something that would make this whole nation feel what an accursed thing slavery is.” Her book told stories of people treated as property, personalizing slavery in a way never done before. Readers learned about Tom, so valuable in economic terms that his sale redeemed his owner’s gambling debts but cost Tom dearly as he was sent south away from his wife and children; and Eliza, who escaped from bondage to protect her four year old, Harry, from sale. One going north, one south; one enslaved and one risking all for her and her son’s freedom, Stowe’s characters seized the public imagination and fueled consciences stirred by the growing controversy about slavery. Everyone wanted to see the woman who had written this great book.

In Great Britain (where slavery had been abolished in 1834) and other European countries, Uncle Tom’s Cabin was also widely read—by poor farmers and the working middle class, by wealthy landowners and nobility. The easy accessibility of Uncle Tom’s Cabin helped drive sales—and Stowe’s popularity—to unprecedented levels. The book fueled popular culture, inspiring songs, ceramics, scarves, soap, and games. And there was theater. When Stowe landed in Liverpool, 10 versions of her book were on stage in London.

But Stowe was unprepared for the adulation that greeted her on the Liverpool dock that spring day. As far as the eye could see, men and women from all walks of life strained to get a look at her. Her brother Charles Beecher’s diary detailed their arrival: “A line forms and marches past her window. Decent, respectful, each, as he goes by, assumes an unconscious air … Others less particular stand and have a good stare … One little fellow [who]climbed on the cab wheel and got a peep through the window …seemed too impetuous and was seized by the shoulder by the police and pitched out. ‘I say I will see Mrs. Stowe!’ he shouted, and back he came and dove headfirst into the crowd.”

This was just the beginning of a tumultuous visit rivaling a 21st-century pop star’s concert tour. In Glasgow, Edinburgh, and Aberdeen, Scotland, throngs shouted, cheered, pushed and shoved at every train station. Boys tried to jump on her moving carriage to peek in the window. The evening “soirees,” or public gatherings, held in her honor were standing room only. She received hundreds of invitations and got used to dining with prominent citizens. Charles spent hours each day futilely attempting to keep up with her correspondence and overbooked social calendar.

Stowe had been invited by British abolition groups. She also had business reasons to make the trip: Because there were no international copyright laws protecting an American work from foreign publication, by December 1852 a dozen different editions of Stowe’s book had been printed in Great Britain—for which she received no royalties. Sampson Law, a London bookseller and commenter on the trade, wrote that “fine art-illustrated editions” were available for 15 shillings and “cheap popular editions” for as little as several pennies. “The discovery was soon made that any one was at liberty to reprint the book, and the initiative was thus given to a new era in cheap literature, founded on American reprints.”

A copy of Uncle Tom’s Cabin was initially brought to England in 1852 by a traveler from Boston who had purchased it the day his steamer sailed. He gave it to a friend, who was so impressed that he helped finance the first British printing. The London firm Clark & Company printed the first 7,000 British copies that April. As Stowe’s son Charles reported in his 1889 Life of Harriet Beecher Stowe, the London printer Mr. Salisbury, considering whether his firm should print Uncle Tom’s Cabin, recounted : “I sat up till four in the morning reading the book, and the interest I felt was expressed one moment by laughter, another by tears. Thinking it might be weakness and not the power of the author that affected me, I resolved to try the effect upon my wife (a rather strong-minded woman). I accordingly woke her and read a few chapters to her. Finding that the interest in the story kept her awake, and that she, too, alighted and cried, I settled in my mind that it was a book that ought to, and might with safety, be printed.”

Harriet and Calvin Stowe, 1863.

By July the book was flying off shelves at the rate of 1,000 copies a week. At one point 18 London printers were working to keep up with what one publisher called “the great demand that had set in.” By the fall of 1852, more than 150,000 copies had been sold throughout Britain “and still the returns of sales show no decline,” according to Clark & Company. In just a year, 1.5 million British copies of Uncle Tom’s Cabin were sold. The book also was gaining ground across Europe. London’s Morning Chronicle called it “the book of the day,” citing its circulation in Europe as “a thing unparalleled in bookselling annals,” and The Eclectic Review, a respected literary magazine published in London, agreed: “Its sale has vastly exceeded that of any other work in any other age or country.”

The May 13, 1853 Hull Packet and East Riding Times (of Hull, England) reported, “Mrs. Stowe’s name is in every mouth. She is the lioness of fashionable circles. She sits with the Duchess of Sutherland on her right hand and the Duchess of Argyll on her left, to receive the homage of England’s nobility. Everybody has read Uncle Tom’s Cabin and everybody knows who wrote it. The columns of the London papers tell us to an inch how tall she is …”

Traveling with Stowe were her husband, the Rev. Calvin Ellis Stowe, a clergyman and biblical scholar; Charles Beecher, her younger brother, also a clergyman; Sarah Buckingham Beecher, her sister-in-law and widow of her brother George Beecher; George, Sarah’s 12-year-old son; and William Buckingham, Sarah’s brother. Sarah, young George, and Charles all kept diaries of the trip. And each traveler wrote letters home. Stowe used the diaries and letters to write Sunny Memories of Foreign Lands, her 1854 memoir of the trip. (The Stowe Center published Charles’s journal in 1986 as Harriet Beecher Stowe in Europe.)

“…The great mass of readers in nearly every country— appear to have come to the conclusion that [Uncle Tom’s Cabin] is the most captivating work ever produced by a woman, or man either, for that matter…” Illustrated London News, 1853.

Still, Stowe was pleased by her reception in Great Britain. She recorded her first impressions of that extraordinary welcome in Liverpool in Sunny Memories: “Much to my astonishment, I found quite a crowd on the wharf, and we walked up to our carriage through a long lane of people, bowing, and looking very glad to see us. When I came to get into the hack [carriage]it was surrounded by more faces than I could count. They stood very quietly, and looked very kindly, though evidently much determined to look.” Stowe’s account was more modest than Charles’s. He wrote about “a great rushing and pushing” and being “chased by a crowd, men, women, and boys” as her carriage moved away from the dock.

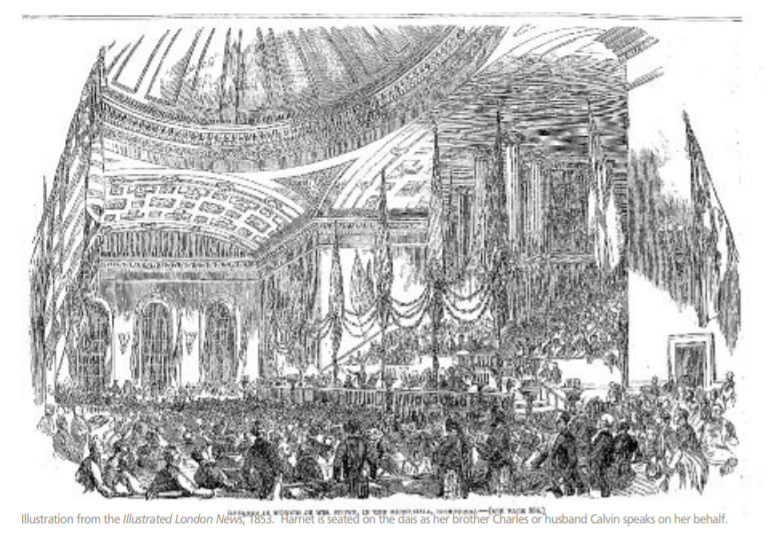

Stowe created a sensation wherever she went. Antislavery groups organized public events featuring her as the main attraction. In Glasgow, an audience of 2,000 gathered for seven hours to sing hymns, listen to speeches, and see what the famed American author actually looked like. When Stowe arrived, the crowd went wild. “When they welcomed her,” Charles wrote, “they first clapped and stomped, then shouted, then waved their hands and handkerchiefs, then stood up—and to look down from above, it looked like waves rising and the foam dashing up in spray. It seemed as though the next moment they would rise bodily and fly up.”

In the countryside, admirers lined the route waiting for her carriage. As Stowe described in Sunny Memories, “We found that the news of our coming had spread through the village. People came and stood in their doors, beckoning, bowing, smiling, and waving their handkerchiefs, and the carriage was several times stopped by persons who came to offer flowers …”

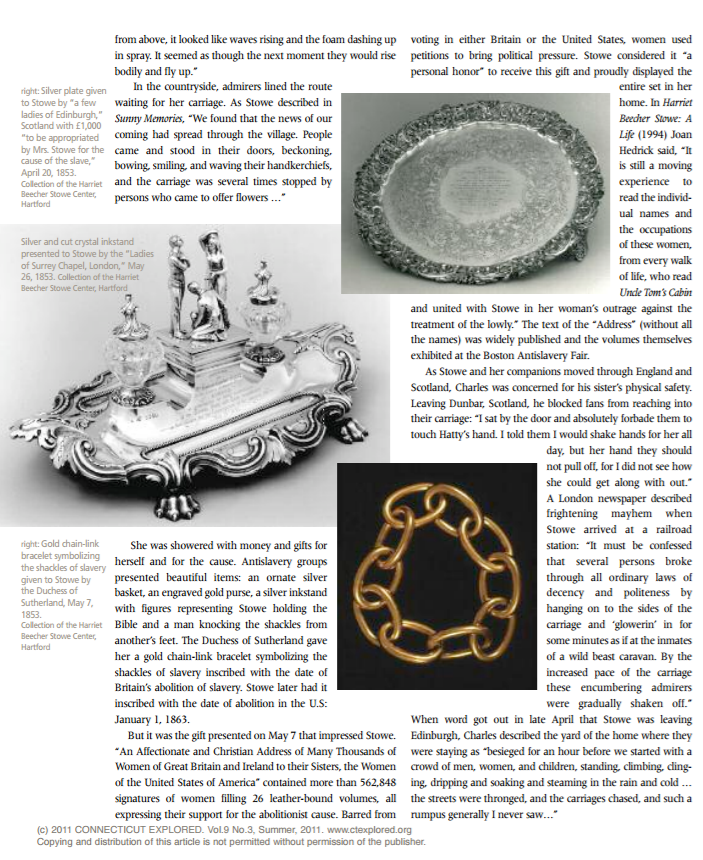

She was showered with money and gifts for herself and for the cause. Antislavery groups presented beautiful items: an ornate silver basket, an engraved gold purse, a silver inkstand with figures representing Stowe holding the Bible and a man knocking the shackles from another’s feet. The Duchess of Sutherland gave her a gold chain-link bracelet symbolizing the shackles of slavery inscribed with the date of Britain’s abolition of slavery. Stowe later had it inscribed with the date of abolition in the U.S: January 1, 1863.

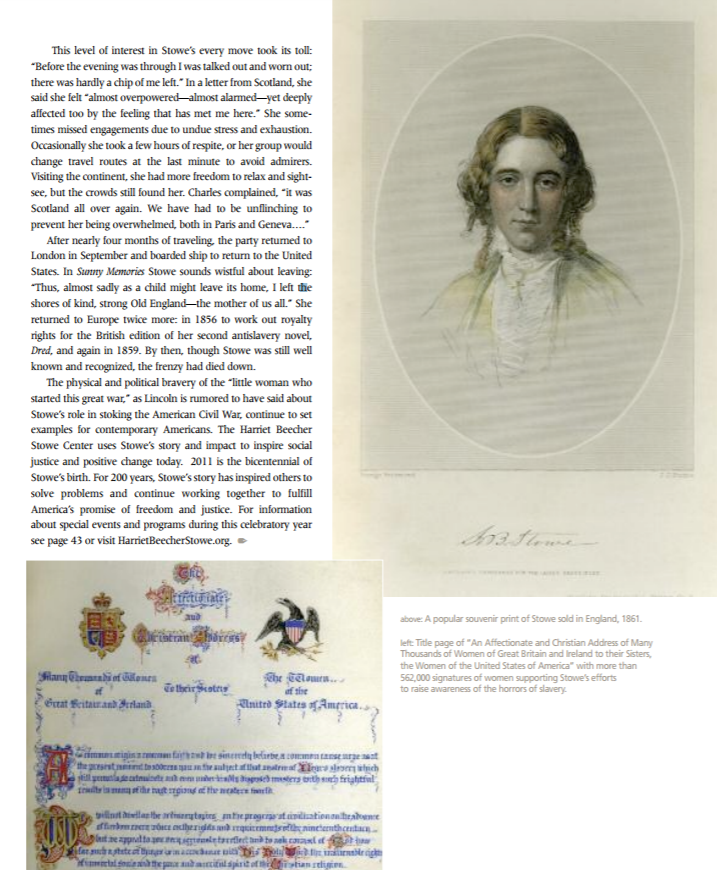

But it was the gift presented on May 7 that impressed Stowe. “An Affectionate and Christian Address of Many Thousands of Women of Great Britain and Ireland to their Sisters, the Women of the United States of America” contained more than 562,848 signatures of women filling 26 leather-bound volumes, all expressing their support for the abolitionist cause. Barred from voting in either Britain or the United States, women used petitions to bring political pressure. Stowe considered it “a personal honor” to receive this gift and proudly displayed the entire set in her home. In Harriet Beecher Stowe: A Life (1994) Joan Hedrick said, “It is still a moving experience to read the individual names and the occupations of these women, from every walk of life, who read Uncle Tom’s Cabin and united with Stowe in her woman’s outrage against the treatment of the lowly.” The text of the “Address” (without all the names) was widely published and the volumes themselves exhibited at the Boston Antislavery Fair.

As Stowe and her companions moved through England and Scotland, Charles was concerned for his sister’s physical safety. Leaving Dunbar, Scotland, he blocked fans from reaching into their carriage: “I sat by the door and absolutely forbade them to touch Hatty’s hand. I told them I would shake hands for her all day, but her hand they should not pull off, for I did not see how she could get along with out.” A London newspaper described frightening mayhem when Stowe arrived at a railroad station: “It must be confessed that several persons broke through all ordinary laws of decency and politeness by hanging on to the sides of the carriage and ‘glowerin’ in for some minutes as if at the inmates of a wild beast caravan. By the increased pace of the carriage these encumbering admirers were gradually shaken off.” When word got out in late April that Stowe was leaving Edinburgh, Charles described the yard of the home where they were staying as “besieged for an hour before we started with a crowd of men, women, and children, standing, climbing, clinging, dripping and soaking and steaming in the rain and cold … the streets were thronged, and the carriages chased, and such a rumpus generally I never saw…”

This level of interest in Stowe’s every move took its toll: “Before the evening was through I was talked out and worn out; there was hardly a chip of me left.” In a letter from Scotland, she said she felt “almost overpowered—almost alarmed—yet deeply affected too by the feeling that has met me here.” She sometimes missed engagements due to undue stress and exhaustion. Occasionally she took a few hours of respite, or her group would change travel routes at the last minute to avoid admirers. Visiting the continent, she had more freedom to relax and sightsee, but the crowds still found her. Charles complained, “it was Scotland all over again. We have had to be unflinching to prevent her being overwhelmed, both in Paris and Geneva….”

After nearly four months of traveling, the party returned to London in September and boarded ship to return to the United States. In Sunny Memories Stowe sounds wistful about leaving: “Thus, almost sadly as a child might leave its home, I left the shores of kind, strong Old England—the mother of us all.” She returned to Europe twice more: in 1856 to work out royalty rights for the British edition of her second antislavery novel, Dred, and again in 1859. By then, though Stowe was still well known and recognized, the frenzy had died down.

The physical and political bravery of the “little woman who started this great war,” as Lincoln is rumored to have said about Stowe’s role in stoking the American Civil War, continue to set examples for contemporary Americans. The Harriet Beecher Stowe Center uses Stowe’s story and impact to inspire social justice and positive change today. 2011 is the bicentennial of Stowe’s birth. For 200 years, Stowe’s story has inspired others to solve problems and continue working together to fulfill America’s promise of freedom and justice.

Katherine Kane was executive director of The Harriet Beecher Stowe Center.

Explore!

“Lincoln and a Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” Winter 2012/2013

Read stories about Connecticut in the Civil War on our Topics page.

Visit

The Harriet Beecher Stowe Center

77 Forest St, Hartford

HarrietBeecherStoweCenter.org