(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Fall 2019

SUBSCRIBE/BUY THE ISSUE!

On any weekday in Hartford women and children wait at the bus stop at the corner of Main and Gold streets. Lone men claim the steps of Center Church and the benches nearby. Behind the church, the bus stop, and the benches is the Ancient Burying Ground. Hundreds of people walk past each day, while tourists and a few residents walk its shaded paths. In these four acres the dead lie beneath markers carved with motifs of death  heads, saints wearing diadems, and the occasional willow-and-urn. The 400 or so headstones are enclosed by a high fence and gates. A statue of Reverend Samuel Stone, bible in one hand, admonishing finger raised with the other, reminds visitors that Puritans once lived and died here.

heads, saints wearing diadems, and the occasional willow-and-urn. The 400 or so headstones are enclosed by a high fence and gates. A statue of Reverend Samuel Stone, bible in one hand, admonishing finger raised with the other, reminds visitors that Puritans once lived and died here.

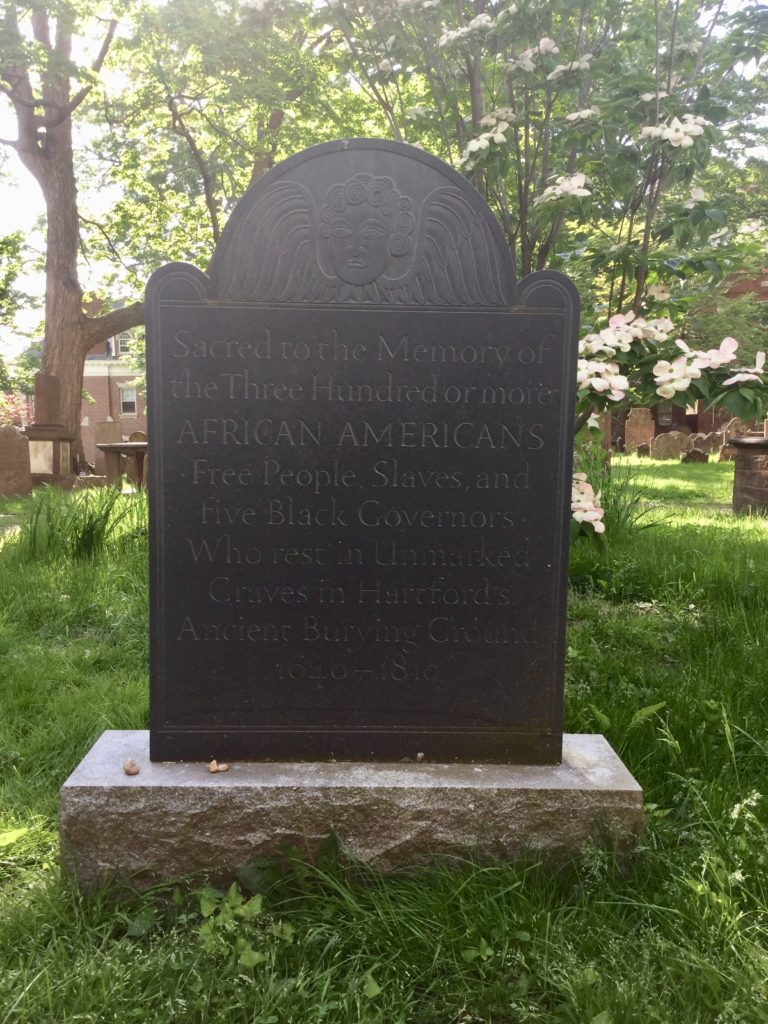

And yet there are few signs in Hartford’s first—and for 150 years, only—burying ground of the non-English, non-Puritan population. No original or replica headstones indicate there were Native, African, and African Americans buried there. Today’s graveyard represents, by design, an homage to the founding white families. A memorial to the colonial-era Black Governors, African-American men elected as leaders by Hartford’s black residents, was erected in 1998 when children from Fox Middle School uncovered facts about the men. (See “Monument to the Black Governors,” Fall 2004.) Another memorial naming some African people buried there abuts it. Still hidden, though, are hundreds of interments of people of color. Far from being people on the margins, Hartford’s people of Native and African descent were absolutely crucial to its development. Their families are also “founders” whose contributions deserve remembering.

Uncovering Their History: Africans, African Americans and Native Americans Buried in the Ancient Burying Ground, a project I directed, was commissioned by the Ancient Burying Ground Association and partially funded by the Connecticut State Historic Preservation Office. It has recovered the stories of people of color who lived and died in early Hartford. In his book African American Historic Burial Grounds and Gravesites of New England (McFarland, 2016), Glenn A. Knoblock estimated there were 300 burials of people of color. The project documented through sexton, probate, court and other records more than 300 people who are likely to have been buried in Hartford’s earliest extant graveyard.

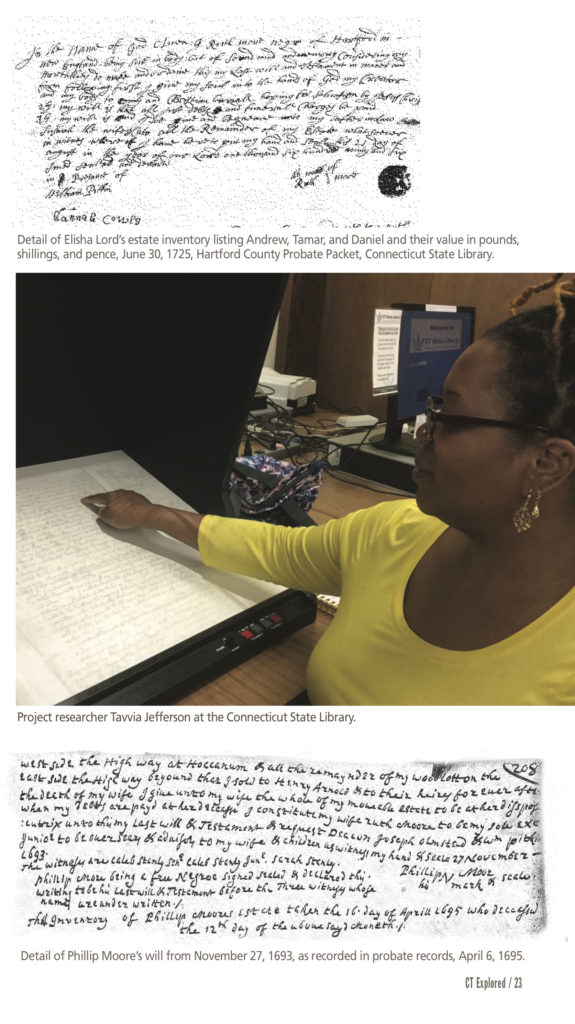

The project team and I assembled the information recounted in the stories below using resources at the Connecticut State Library, including the state archives, Hartford County Probate Packets and Records, the Hartford Land Records, miscellaneous court records, the microfilmed church records of Hartford’s First and Second Congregational churches and First Baptist Church, the Connecticut Courant and other early American newspapers, and published lists of burials including The Historical Catalogue of Hartford’s First Congregational Church, The History of the Second Congregational Church in Hartford, and the town sexton’s list provided by Dr. Charles Hoadly, the state historian, and transcribed by Mary Talcott in 1899.

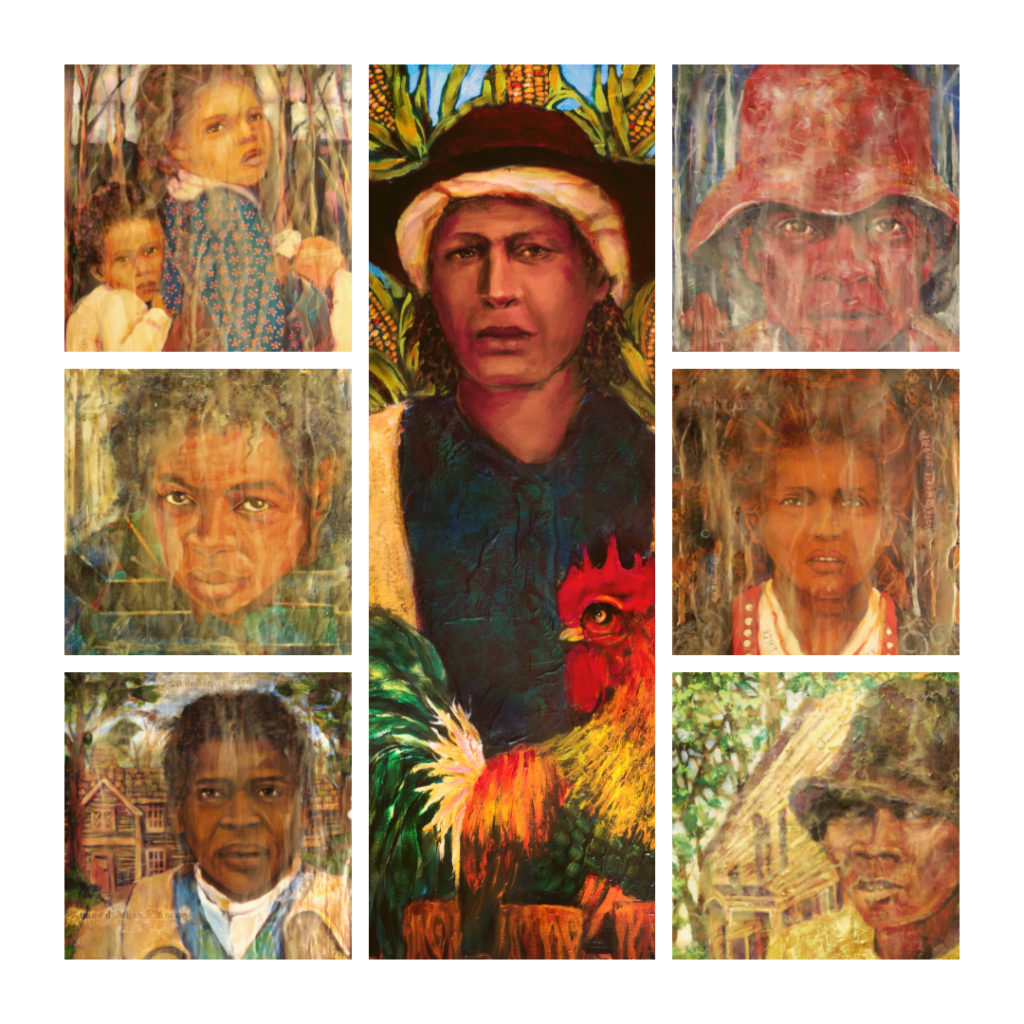

The project carried that research into the emerging field of “digital humanities.” We created a website with details about nearly 500 people, whose profiles are organized in individual listings that act as virtual headstones. The team added public family trees on Ancestry.com so that people can incorporate this research into their own family trees. With the help of computer science students from Central Connecticut State University, I created a computer program called RelationshipTree™ to show relationships that went beyond the familial, such as master-slave, friendship, will-and-beneficiary, and more. With a downloadable database, other researchers can use and perhaps build upon our findings. The artwork of Cora Marshall gives faces to those for whom there are no portraits.

Colonists Bought Suckiog from the Indians and Called it Hartford

It is both a familiar story and one few people know in depth, how Thomas Hooker came in 1636 from Massachusetts to Connecticut and purchased land from a sachem (chief) named Sequassen. In 1631 the Wangunk people who lived in Suckiog had invited English colonists to join them to help provide strength against the Pequot who lived to the south. It took five years for the English to decide to do so. The English had no intention, however, of living under Sequassen or his father, the grand sachem, Sequin.

In 1637 Connecticut and Massachusetts went to war against the Pequot. When the war ended in 1638, Connecticut Colony declared the Pequot name legally extinct. Surviving male Pequot prisoners were sold into slavery in the Caribbean. Women and children were distributed to colonists and Native allies. Hartford thus became home to Wangunk, Pequot, Podunk, and other Native people who were free, indentured, and enslaved.

Native people worked, traded, and socially interacted with residents of English, Dutch, and African descent. For example, the papers of George Wyllys at Connecticut Historical Society document that dissatisfied Native and African residents tore down houses in 1658. Hartford land records show that a man named Japhet owned land and paid property taxes in 1659. Native men like William Wait went with Colonel William Whiting to fight in Queen Anne’s War in 1709. When Wait died in 1711 his estate was probated in the Hartford County Court. Sarah Onepenny the Elder, a descendant of Sequin, who served Col. Whiting, died in Hartford, probably at Whiting’s home. An oral will in the probate records and an entry in the colony records show Whiting’s daughter Mary, Sarah’s children, and her sister Hannah were at her bedside in 1713. A Wangunk medicine man, Doctor Robin (also called “Old Robin”) came up from Middletown in 1757, perhaps to treat Black Betsey and her sick baby. Their deaths and burials were recorded in the sexton’s records. These and other Native people, named and unnamed, were buried alongside settlers in the Ancient Burying Ground. The last recorded Native person to be buried in the Ancient Burying Ground, on April 1, 1795, was “the Child of Abigail, an Indian Woman.”

Here Lies Phillip Moore…

On the east side of the Connecticut River in a place called Hockanum, Phillip Moore cultivated crops of rye and Indian corn. In May he scattered flax seed. His children harvested it in midsummer. Each fall he picked apples from his seven-acre orchard. He grazed his livestock–a mare, a sow, a pig and a cow–on two acres of pasture land he kept cleared. He cut wood on 36 acres of woodland. Tools made his work easier. A winnowing fan helped him separate grain from chaff. He had an apron chain, possibly for spreading manure or moving rocks. He had a trace chain and whiffletree or whippletree chain, the pivoted, swinging bar attached to a draft animal’s harness, Hartford County probate records show.

On the east side of the Connecticut River in a place called Hockanum, Phillip Moore cultivated crops of rye and Indian corn. In May he scattered flax seed. His children harvested it in midsummer. Each fall he picked apples from his seven-acre orchard. He grazed his livestock–a mare, a sow, a pig and a cow–on two acres of pasture land he kept cleared. He cut wood on 36 acres of woodland. Tools made his work easier. A winnowing fan helped him separate grain from chaff. He had an apron chain, possibly for spreading manure or moving rocks. He had a trace chain and whiffletree or whippletree chain, the pivoted, swinging bar attached to a draft animal’s harness, Hartford County probate records show.

Like most colonists, Phillip and Ruth raised their family with few luxuries. Two iron pots, a brass skillet, an iron kettle, and a pewter frying pan served as the family’s cookware. An iron trammel hung in the fireplace. Although pewter was “the poor man’s silver,” Ruth valued it enough to want her daughter Susanna to have it when she died. Ruth had cards to work wool for spinning, but she had no spinning wheel. She may have taken her wool somewhere else to have it made into yarn.

Their eldest son, Phillip Jr., had a few scrapes with the law as an adolescent, though he eventually married and raised a family. His wife Lydia became a member of the First Church of Christ in Hartford, the church founded by Hooker and Stone. All of their children were baptized there. When Phillip Sr. and Ruth died in 1695 and 1696, respectively, they left wills, and administrators took inventories of their goods. Their son Phillip passed away in 1698.

Yet for all that the Moores were like most colonists, they were also highly distinguishable, because they were of African descent. They appear in land records as a farm-owning family around the time of King Philip’s War (1675 – 1676). In some, but not all, records they were designated as “Negro.” As Christian people, their neighbors and fellow church members may have felt it unnecessary to mark them as “strangers,” i.e., as non-English. When the Moores died, they were buried, like their neighbors, in Hartford’s Ancient Burying Ground. A bill for Phillip Moore Jr.’s coffin and grave shows a colonist, Jonathan Ashly, took care of the arrangements. But no headstones exist for the Moores.

After Phillip Jr.’s death, the family’s fortunes slowly declined. Phillip Jr. and Lydia’s daughter Sarah bore children out of wedlock and wound up on poor relief, taken into the home of the Moore’s white neighbor, Thomas Seymour. Over time the Moores quitclaimed their land to white neighbors. The family’s fiscal and social decline came as the colony’s investment in African slaves rose. Free people of color faced increasing racism as enslavement came to define the status of most people who looked like them. Philip Moore, Sr.’s daughter, Susanna, married Cato Serious, a man indentured to Rev. Timothy Woodbridge, minister of the First Congregational Church. Serious acquired land that their daughter Priscilla later quitclaimed. It is possible that hard times forced them into continued servitude, or they may have moved to find better opportunities. The family’s female members could have married and changed their surnames. As mysteriously as they arrived in the records, they departed.

Only in Death Were They Free

Africans arrived in the Americas via the Middle Passage. Sometimes captive people were transported to the West Indies, to places like the Cabbage Tree Plantation in Antigua, which was owned by merchants Richard Lord and Samuel Wyllys, who then brought them to places like Hartford. Andrew may have been such a person, a young boy probably when he was captured and put to work. He came with Lord to Hartford, and when his master died in 1685, lost at sea, he became the possession of Lord’s son Richard. When that Richard Lord died in 1711, Andrew passed to his widow, Abigail Lord.

Abigail Lord’s second husband was Rev. Timothy Woodbridge, who owned Tamar, a maidservant. Tamar bore a child, Lydia, in 1720, and then she and Andrew were wed in 1721. They had two more children in quick succession, Isabella and Daniell, who, along with Lydia, were baptized at Hartford’s First Congregational Church. After Abigail’s son Elisha Lord got married, she and Rev. Woodridge gave Andrew, Tamar, and son Daniell to the newlyweds, separating them from their daughters Lydia and Isabella. When Rev. Woodbridge died, Lydia passed to his daughter Susanna Treat. When Andrew, Tamar, and Daniell eventually died, they were buried in the Ancient Burying Ground. Isabella and Lydia’s final resting places are unknown. Although Andrew, Tamar, and their children may have experienced some relative stability by remaining with the same extended white family, nothing about their lives was under their control. They passed through a sea of Lords and Woodbridges, and, like other passages, these too parted loving family members from one another.

Traded, sold, given as gifts, and subjected to beatings, as documents attest, the enslaved people of Hartford suffered no less than enslaved people anywhere. When they died, they were often treated no better in death than they had been in life. The burying ground held the remains of at least 115 people of African descent who went unnamed in the sextons’ records. In the 17th century William Goodwin recorded the deaths of black individuals with dates but often without names or sex. A typical entry marked the death of one unnamed person on December 29, 1693, noting the individual belonged to a Mr. Allyn. Another, who belonged to a Mr. Talcott, died June 4, 1697. And so on. Goodwin surely knew them, but he didn’t name them. Others who kept lists of burials did the same. Some of the dead never even made the sextons’ lists, their names known only from other records. In these cases, we assumed they were likely buried in the town’s only burial ground and noted this uncertainty in the database.

Yet, some enslaved people were named in the sexton’s records. Those who were the property of learned professionals like ministers, doctors, and lawyers appeared with English names and occasionally African ones, such as Quaw (owned by Rev. Timothy Woodbridge), Dinah (owned by Dr. William Jepson), and Gill (owned by John Ledyard, Esq.). The project database graphically demonstrates the gross inequities of life and death for people of color.

Gradually They Were Emancipated

In 1784 Connecticut passed a law to abolish slavery, slowly. In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, Hartford swelled with newly freed black people. Mingling with the population of Africans and African Americans already in Hartford, these newcomers formed families, more children were born, and more people died, especially the infants. By 1800 the Ancient Burying Ground had nearly 6,000 bodies of all races resting there. The city opened other graveyards to the south and to the north. By 1806 the burials in the Ancient Burying Ground slowed, and by 1815 new burials had ceased.

Newcomers like Ned Dolphin and his wife Fanny, who arrived in Hartford by 1788, bore many children, but infant mortality was high for people of color, and several died. Likewise, Neptune and his wife Priscilla watched as their children succumbed to a variety of illnesses. Neptune was a respected barber and honorary “black sheriff.” Lucy, an indigent “mulatto” woman, had two children who died, one in 1781 and the other in 1790, both of whom were buried “at the charge of the town.” When Lucy died, a black man named Peter stepped forward to pay for her burial.

The path out of slavery was difficult. Sally Cuff purchased her freedom by paying £100 to John Haynes Lord, her master and one of Hartford’s wealthiest men. She probably earned that money doing additional work after her daily labor for Lord was finished. Benjamin Concklin owned Mark, age 13, whom he sold to Freeman Kilborn for $33 in August 1788. Kilborn then sold Mark to Jeremiah Wadsworth for the same amount, according to Jeremiah Wadsworth’s papers at CHS. In December 1796 Mark’s daughter Sally, noted as free in the baptismal records, was baptized in Hartford’s Second Church of Christ. The church records indicate little Sally died at two years old, stricken with consumption (tuberculosis).

Manumissions occurred throughout Hartford’s history. Sometimes masters and mistresses developed scruples about keeping people in bondage and freed them during their lifetimes. Others did so in their wills. Some enslaved people employed the law to free themselves. Abda Duce-Ginnings was the son of Thomas Richard’s enslaved maid, Hannah Duce, and a white man, John Ginnings, who had sexually assaulted her in 1673, according to Hartford County Court minutes. He sued Richards for his freedom in 1703 on the grounds that he had a free English father. While the courts found against him, judging him heritable property, Richards eventually freed him, perhaps to prevent further litigation. Duce-Ginnings married a free woman named Lydia, with whom he had a son, Joseph Duce (also sometimes referred to as Joseph Ginnings and Joseph Jennings). Duce lived as a free man, dying in 1789 in Hartford at the old age of 87.

Resting in Peace, Living Online

The Ancient Burying Ground was never a static place. Buildings have gone up and come down, graves have been disturbed during construction, and bodies and tombstones have been moved over the centuries. While their graves are no longer marked, their marks on Hartford are now visible and indelible. We invite everyone to visit the website at africannativeburialsct.org.

Katherine Hermes, J.D., Ph.D. is a professor of early-modern Atlantic World history at Central Connecticut State University. She is the author of several articles, essays and book chapters on Native American legal history, and with Alexandra Maravel is working on a legal biography about an African-Wangunk man, Scipio Brown.

Explore!

“Monument to the Black Governors,” Summer 2004

Grating the Nutmeg podcast episode 78

More about cemeteries:

“Site Lines: Grave Deeds and Abandoned Cemeteries” Summer 2019

“Cedar Hill Cemetery: More Than Just a Resting Place for the Dead” Summer 2005

“Benjamin Collins, Rock Star,” Spring 2015

“Beauty in a Gravestone,”

Read more stories about Native American and African American history on our TOPICS pages.