By Linda Pagliuco

By Linda Pagliuco

All photos by Linda Pagliuco

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Winter 2010/2011

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

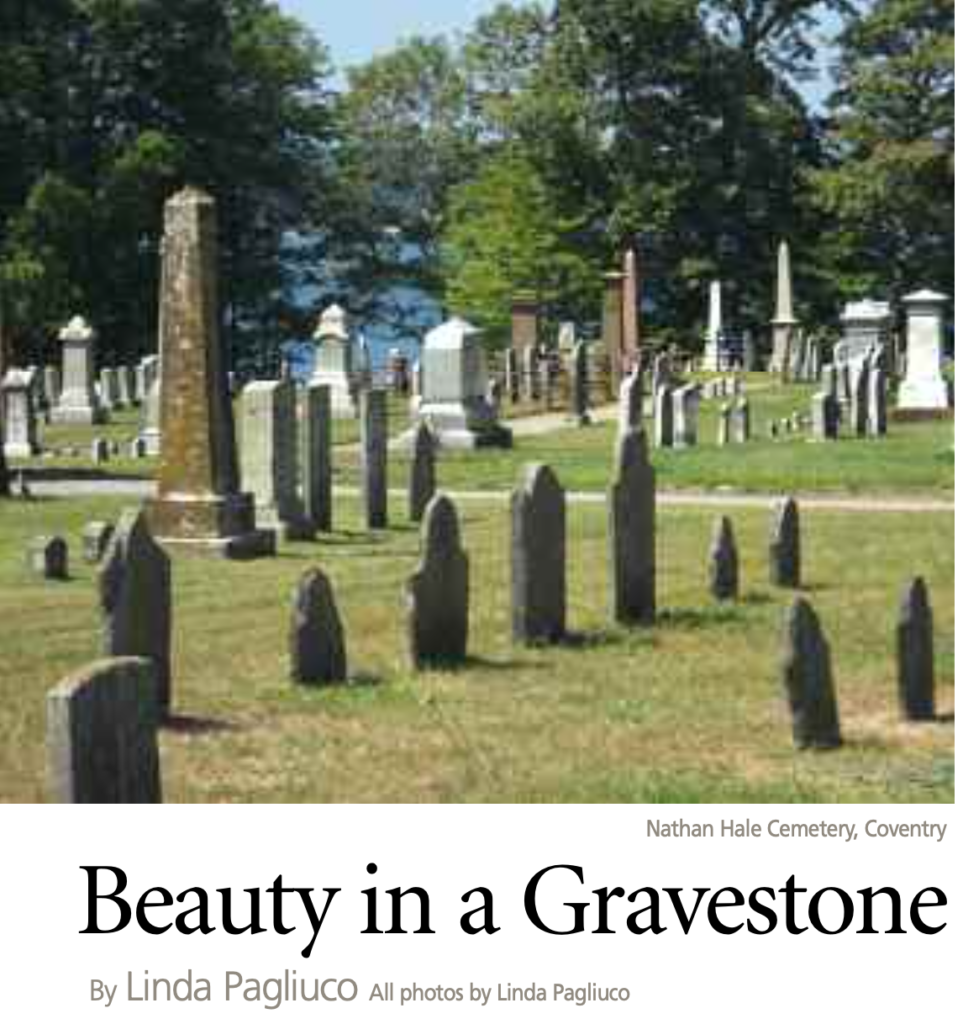

Across the rolling granite hills of eastern Connecticut lie scattered dozens of ancient graveyards, or, in the parlance of their time, burying grounds. Dating from the founding of our communities early in the 18th century, their weathered gravestones now tilt haphazardly across the landscape like rows of crooked teeth. While the original purpose of these places is self-evident, today an informed visitor, armed with curiosity, a bit of patience, and a sharp eye can uncover in them mysteries, historical detail, and insights into the lives of those who came long before us.

Gravestones are one of colonial America’s earliest forms of sculptural art, created by a culture that disapproved of “graven images.” The words and images carved into the stone were intended to convey a message to the living, reflecting contemporary religious beliefs about death. In the 17th century, the stark visage of a skull was the most common motif, sometimes accompanied by related symbols, such as a scythe, an hourglass, or a coffin. Pioneering researcher James Deetz interpreted these images as personifying the harsh views of the Puritan religion, a view that is widely accepted today. Death (the coffin) will come sooner than you think (the hourglass), they warn us, so beware and be ready to face judgment, which is likely to be harsh (the scythe). But beliefs and styles change, and a departure from the grimness of early Puritan thought lead to a modification of those motifs in the 18th century.

Gravestone of Huckens Storrs, granite, 1784, carved by the Manning family. Mansfield Center Cemetery, Mansfield. photo: Linda Pagliuco

As you stroll between the rows of an 18th-century burying ground, you’ll notice that the oldest grave markers are decorated at the top by small faces surrounded by wings. Most historians agree that these whimsical, sometimes fearsome images are meant to be “soul effigies” or “cherubs.” As no contemporary written documentation about the meanings of gravestone imagery has been found, caution must be taken when attempting to interpret them, and it is difficult to do so with certainty. Today, we surmise that these winged heads symbolize the spirit of the departed, separated from the body by death. The wings are thought to represent the ascension of the soul to its final reward. The variations among these faces are many, as most carvers favored their own particular style.

Who were these carvers? According to Connecticut researchers Ernest Caulfield and James Slater, most of New England’s early stones were made by local stonemasons or quarry owners, who also produced such items as foundation blocks, mantle surrounds, door jambs, and steps. More highly skilled professionals in the larger cities turned out small masterpieces of sculpture with ogee curves, garlands, and copperplate. The Manning family of Mansfield turned out hundreds of beautiful markers, large and elaborate. But most rural carvers had little formal training or knowledge of art. Some were illiterate and only able to make a copy of text provided to them by the customer, their lettering clumsy and their decorations derived from folk art. Borders on their stones contain such charming, traditional figures as hearts, daisies, and pinwheels.

Tombstones, then as now, were costly; thus, there are many more graves left unmarked than marked, an interesting fact to ponder. Prices were set by size and shape and by the number of letters in the inscription. Few people could afford such a luxury, and those who could generally contented themselves— and their pocketbooks—with the commemoration of the departed’s name, date of death, and age at death. Loved ones with more resources might include a verse at the bottom or add the cause of death (“drowned in the great pond”), and some stones are virtual history lessons. For instance, whoever commissioned the stone for Esther Williams Meacham, wife of the esteemed minister at Coventry, Connecticut, arranged for a concise summary of her kidnapping during the infamous 1704 Indian raid at Deerfield, Massachusetts, where she was born, raised, and survived the attack.

Gravestone of Esther Williams Meacham with the winged head motif, granite, 1751, carved by Gershom Bartlett. Etched on her stone is the story of her girlhood survival of the infamous 1704 Indian raid at Deerfield, Massachusetts. Nathan Hale Cemetery, Coventry. photo: Linda Pagliuco

Esther’s stone, in Coventry’s Nathan Hale Cemetery, was made by Gershom Bartlett, who owned the granite quarry at what is now called Bolton Notch. Sharp-eyed readers of her epitaph may note an error, where Bartlett omitted the letter e in the word frind, meant to be friend. Someone caught his mistake, but there was no starting over. Bartlett (or someone else) inserted the missing letter above the word in question. Carver Jonathan Loomis forgot to include the death date of Elisabeth (sic) Palmer, and had to squeeze the numerals in between the lines. On other stones, reversed or missing letters, skipped words, and shallow holes where mistakes were “erased” can frequently be spotted. In the days before Noah Webster and dictionaries led to standardized spelling, all sorts of phonetic variations were used. Punctuation can be either meticulous or nonexistent, for example, the stone made for “Skillfull Faithfull Phycetion Mr John Mead,” and the hundreds of inscriptions beginning “Hear Lyeth the Body.” Mary Badcock died in “ye 58 year of hur Age.”

At the turn of the 19th century, gravestone iconography changed once again. The classical urn-and-willow design supplanted the soul effigy.

Our precious early markers are eroding very quickly, and many old stones are now completely illegible. “Written in stone,” alas, does not mean forever. Take a stroll through a nearby burying ground to appreciate this legacy of folk art and sculpture before it disappears forever.

Linda Pagliuco has worked for more than 20 years as a docent and educator at Connecticut Landmarks’s Nathan Hale Homestead in Coventry and, more recently, at the Webb- Deane-Stevens Museum in Wethersfield. Her primary areas of interest are historic cemeteries and textile arts.

Explore!

“Site Lines: Grave Deeds and Abandoned Cemeteries” Summer 2019

“Cedar Hill Cemetery: More Than Just a Resting Place for the Dead” Summer 2005

Hartford’s Ancient Burying Ground: “Unburying Hartford’s Native and African American Families,” Fall 2019

“Benjamin Collins, Rock Star,” Spring 2015