By Billie M. Anthony

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. AUG/SEP/OCT 2004

Subscribe!/Buy the Issue!

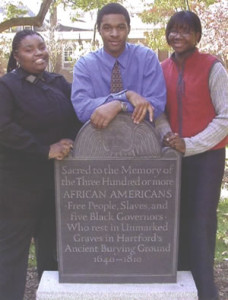

Hartford students Andriena Baldwin, Christopher Hayes, and Monique Price with the African American Monument they researched and raised the fund to erect, 1998. photo: Billie M. Anthony

Captured Africans were first brought to Connecticut in the 17th century to work in the seaports, towns, and on farms. However, they and their descendants kept alive their African history and customs, one of which was electing a leader. In Connecticut this old African custom was practiced through the mid-1800s, and the leaders were designated the Black Governors, six of whom came from Hartford.

A man was elected governor for his wisdom, strength, honesty, and for the respect that he commanded. He often appointed his own officers who helped him keep the peace. The names and years of elections for most of the Black Governors have been known for many years, thanks to anecdotal sources and local historians, especially the late John E. Rogers, a member of the Connecticut Historical Commission and an associate professor of Black history at the University of Hartford and Greater Hartford Community College.

From 1995 to 1997 students Andriena Baldwin, Christopher Hayes, and Monique Price from Hartford ‘s Fox Middle School led the research and fund-raising efforts to honor the 300 or more African Americans interred in unmarked graves in Hartford ‘s Ancient Burying Ground. They discovered that five of Hartford ‘s Black Governors were likely buried there. The students used primary sources–census, probate, church, and land records–to uncover and document the African presence. With the assistance of the Ancient Burying Ground Association and a committee of students, parents, and representatives from the Center Congregational Church and the Historical Commission, the African Americans interred in the Ancient Burying Ground, including the five of the Black Governors, were commemorated in 1998 with a unique hand-carved black slate memorial.

In the Connecticut State Library archives the students found the bill of sale for London, elected governor in 1755. He was purchased for £60 on September 11, 1725 by Thomas Seymour, the grandfather of Hartford ‘s first mayor. Governor Quaw, elected in 1760, was owned by Colonel George Wyllys, secretary of the colony and later the state. Governor Quaw’s election party was held at Amos Hinsdale’s tavern, which stood near present-day South Park. Governor Cuff was elected in 1766 and resigned from office in 1776. John Anderson, the personal slave of Major Philip Skene (a British prisoner of war who was held in Hartford), succeeded him in 1776.

The announcement that Anderson was the new “Governor of the Slaves” and that a good sum of money had been paid for his election party at Knox Tavern aroused great suspicion, as there hadn’t even been an election! An immediate investigation found no evidence of conspiracy, but there exists a document signed by both Governor Cuff and John Anderson states that Cuff resigned because he was “weak and unfit” and that he had appointed Anderson in his place. Six Africans or African Americans are listed as witnesses. Not long after, Major Skene escaped from the Americans and John Anderson disappeared from history.

One of the most interesting Black governors was Peleg Nott, owned by Colonel Jeremiah Wadsworth a Hartford businessman and representative to Congress who was the richest man in Connecticut. Nott participated in the American Revolution, driving a provisions cart. He was a man of considerable reputation, entrusted with money, goods, and later farmland in what is now West Hartford. He was elected governor in 1780 and celebrated the election in the African custom of a grand parade. An eyewitness places him on a “frisky horse.” Wadsworth eventually freed Nott and his wife, and they probably lived somewhere near where the Wadsworth Atheneum now stands.

Boston Nichols of Hartford, described as a “stable and respectable man,” was married to a woman named Rose. In 1774 Captain James Nichols freed them and in 1783 he granted Boston some land and a house for five pounds. This site was near the old Charter Oak tree, on what is now called Wyllys Street. According to accounts pieced together by the student researchers the place on the 1790 map of Hartford identified as “Negro house” was where Boston Nichols and Rose lived. In 1800 Boston Nichols was elected Governor of the Blacks. When he died in 1810, he was buried in the Ancient Burying Ground with his “cocked hat” and his sword on his coffin. The exact whereabouts of his grave are unknown, but his life is memorialized on the ledger stone of the African American monument.

In recent years, the stories of the Black Governors and their families have begun to be recovered and restored to Connecticut ‘s history. Inspired by the students’ work, others have organized to further the research and tributes. In 2001, the Connecticut General Assembly, through the Connecticut Freedom Trail, commissioned Dr. Katherine Harris of Central Connecticut State University to conduct research on Connecticut ‘s Black Governors. In addition to bringing the total to 27, Dr. Harris uncovered myriad personal stories and fascinating details. The John E. Rogers African American Cultural Center was one of the first historical groups to honor the Hartford students for their work; and that organization has held Black Governors Ball and circulates an exhibit on the Black Governors.

The Ancient Burying Ground is located at Main and Gold streets in Hartford, adjacent to Center Church.

Billie M. Anthony was the African-American Memorial Project Teacher. She taught at Fox Middle School in Hartford for 26 years. This essay also appears in African American Connecticut Explored (Wesleyan University Press, 2014) along with two additional essays by Katharine Harris about the Black Governors.

Explore!

Read more stories about politics in the Aug/Sep/Oct 2004 issue and on our Governing the Colony & the StateTOPICS page.

Read more stories about the African American experience in Connecticut on our TOPICS page.

Subscribe to receive every issue!