(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Fall 2019

SUBSCRIBE/BUY THE ISSUE!

DNA testing is today’s cutting-edge technology in determining family ancestry. We marvel at its ability to identify relatives, map where our ancestors lived, or identify our genetic makeup. But a century ago, a man from New Haven, Connecticut helped revolutionize ancestry research. Using primary source documents and contextualizing history to create reliable family trees, his revolution was about getting the data right. That man was Donald Lines Jacobus. Born in 1887, Jacobus was an obsessive family researcher. By the end his career he had contributed to more than 70 volumes and 250 magazine articles, founded the journal The American Genealogist (TAG), and earned the nickname “Dean of American Genealogy.” Jacobus’s influence was so great that genealogists who followed his lead in evaluating period sources began referring to themselves as part of the “Jacobus School.”

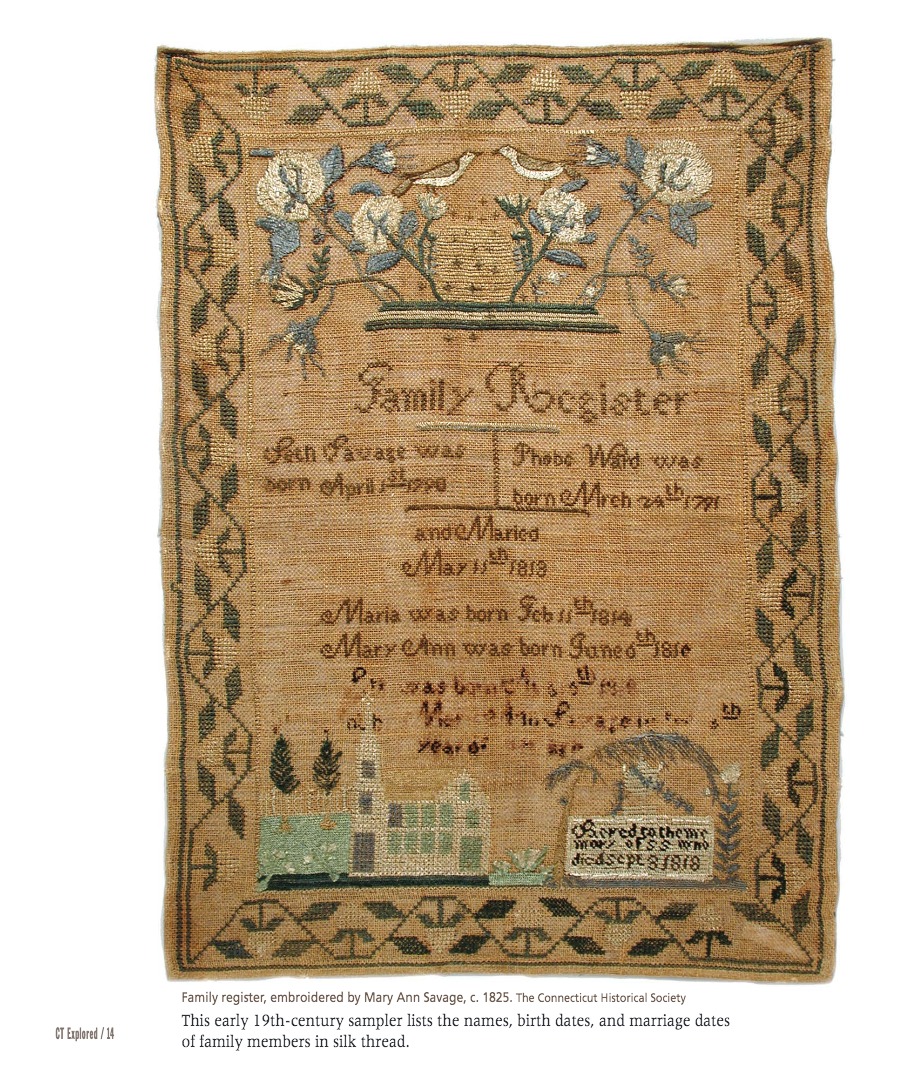

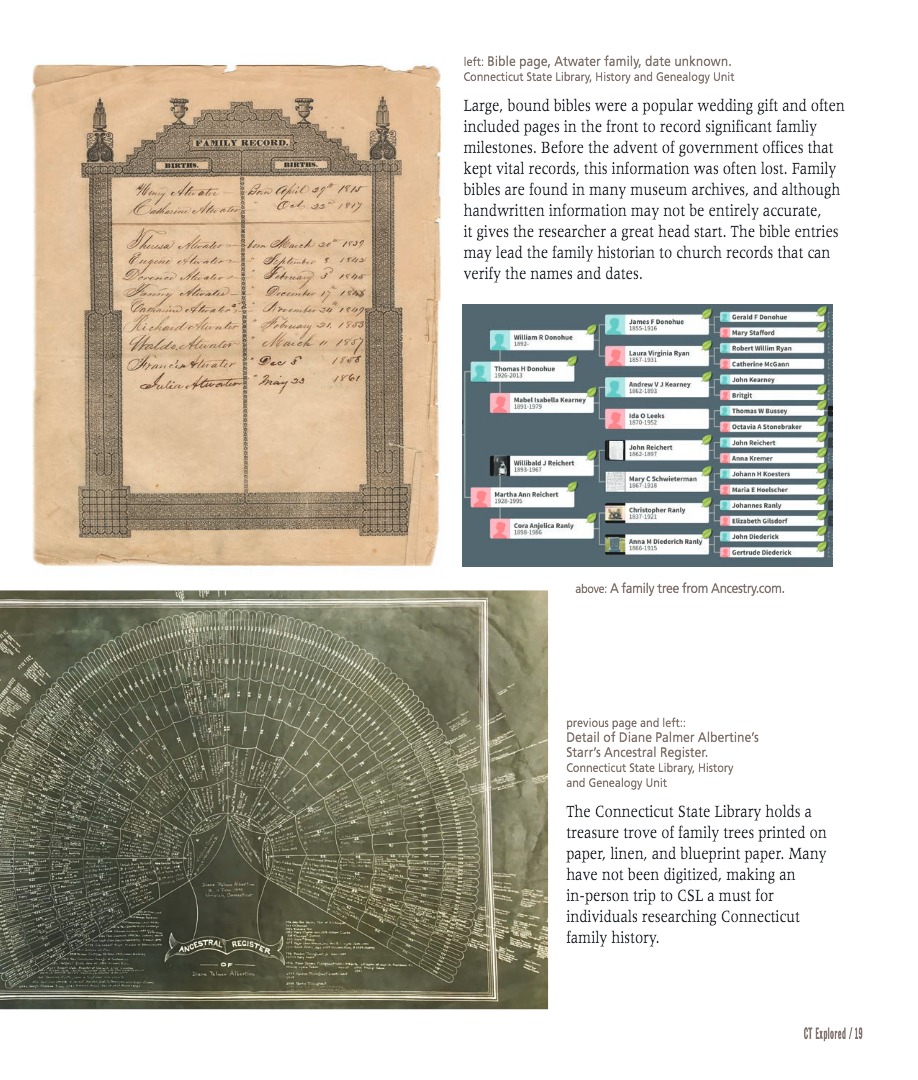

The practice of genealogy gained popularity in the United States as early as the mid-19th century. But these early genealogies often propagated more myth than truth. Relying on family bibles inscribed with birthdays or on the recollections of elderly relatives, early genealogists rarely had the skills or tools to critically analyze such sources for their trustworthiness and often approached research with the goal of locating illustrious ancestors. Genealogy’s increasing popularity only made the situation worse as profit-seeking commercial firms found a ready market for scantily researched family histories, while well-meaning amateurs propagated the errors of their research in self-published volumes.

Jacobus made it his job to interrogate and correct such faulty genealogies. Studying the history of inheritance laws, legal procedures, calendar changes, military service requirements, names and nicknames, spelling variations, and a host of other factors influencing vital records, Jacobus developed the ability to judge other genealogists’ interpretation of primary source documents, publishing written reviews in his journal TAG. Facilitating Jacobus’s work was the construction of new repositories for vital records in centralized libraries and historical societies.

The state of Connecticut pioneered one of the largest such projects, a massive record preservation initiative conducted by state librarian George Seymour Godard between 1900 and 1940. Godard secured private, state, and later federal Works Progress Administration funding to index vital records from cemetery headstones and newspaper death notices. Godard also enlisted the help of a Connecticut chapter of the Colonial Dames to visit local parishes and persuade churches to share their records with the state. The results were assembled and indexed for public use.

By his nature, Jacobus could be a bit of an iconoclast. He took delight in deconstructing the popular image of solemn colonial Americans. In his seminal how-to manual, Genealogy as Pastime and Profession, Jacobus included a chapter dedicated to early American humor, most of which he culled from gravestone epitaphs. Another chapter focused on the prevalence of illegitimacy, a subject that not only allowed Jacobus to uncover early American peccadillos but also provided him with the chance to show off his research skills. Directed as he was by paid commissions, Jacobus’s own research rarely deviated from early American families of European descent. But in Pastime and Profession, he rejected the way genealogy was used to establish social status, calling it “racketeering” in ancestors.

As much as Jacobus discouraged the practice of ancestor worship, he believed in the promise of the now-discredited eugenics to elevate human society with selective breeding. Charts among his papers show that he was experimenting with his own eugenics research—tracking qualities such as “children subject to gout,” “children of great ability,” and “children subject to melancholia.” Jacobus argued for the potential of eugenics in Pastime and Profession, and although no evidence exists to confirm his acceptance, a letter among his correspondence held in the collections of the Connecticut Historical Society shows that he was solicited as a founding member of a New Haven chapter of the American Eugenics Society.

But Jacobus’s research could also be interpreted to refute eugenics. Because he knew the difficulty of tracing bloodlines, Jacobus questioned whether scientists’ family data was reliable enough to make their claims. And while eugenicists regularly tied their theories to explicitly racist ideas, scapegoating African Americans and new immigrants for social problems, Jacobus acknowledged that degeneracy also existed among the families of early European settlers.

Jacobus’s single-minded devotion to research allowed him to transcend the ancestor worship that blinded many of his contemporaries to the family fictions they constructed. Still, one wonders to what degree Jacobus’s evidence-based approach to family research—an approach he and his followers often referred to as “scientific”—gave credence to the idea that human heredity could be understood and manipulated. Certainly Jacobus revived Americans’ faith in their ability to know their ancestors and in doing so helped genealogy win the popularity it has today.

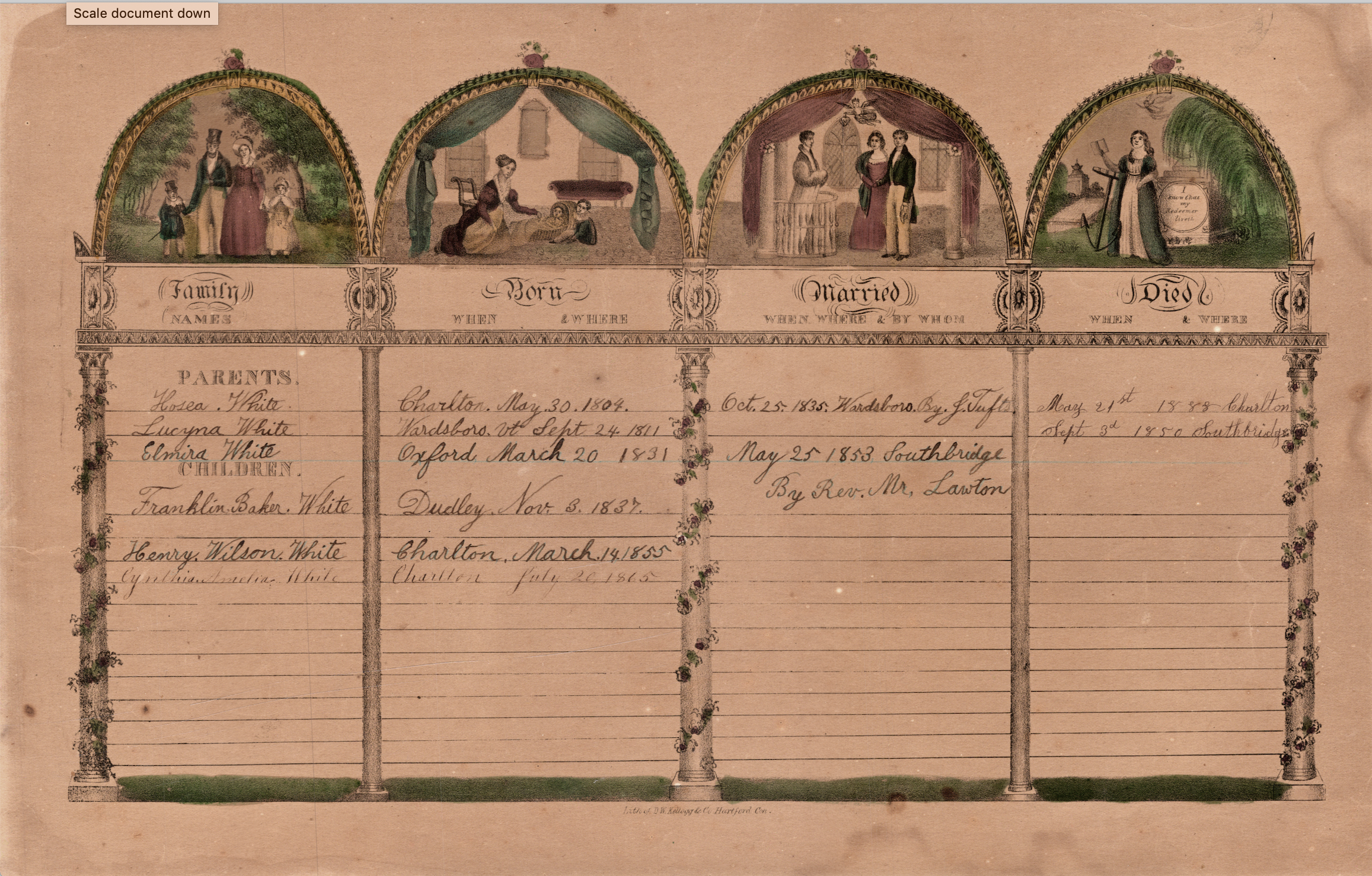

This popular family register was printed and sold by Hartford’s enormously successful Kellogg company. The buyer listed family births, marriages, and deaths under the appropriate scenes. It was just one of many prints sold by the company, which, according to The New York Times (February 4, 1979), sold [?] 600,000 a year in the 1850s for 25 to 75 cents each. The prints were available from Yankee peddlers, at Kellogg’s shops in Hartford and New York, and through sales agents across the country. Memorial, baptismal, and marriage certificates were part of the company’s retail line. ThevKellogg printing company’s half-century of production is chronicled in Picturing Victorian America: Prints by the Kellogg Brothers of Hartford, Connecticut 1830-1880 by Nancy Finlay and Kate Steinway.

Briann Greenfield is executive director of the Harriet Beecher Stowe Center. Her research on Jacobus came from her interest in genealogy as a form of popular history. She last wrote “Selling Connecticut’s Products Abroad” with Dave Corrigan, Winter 2011/2012.