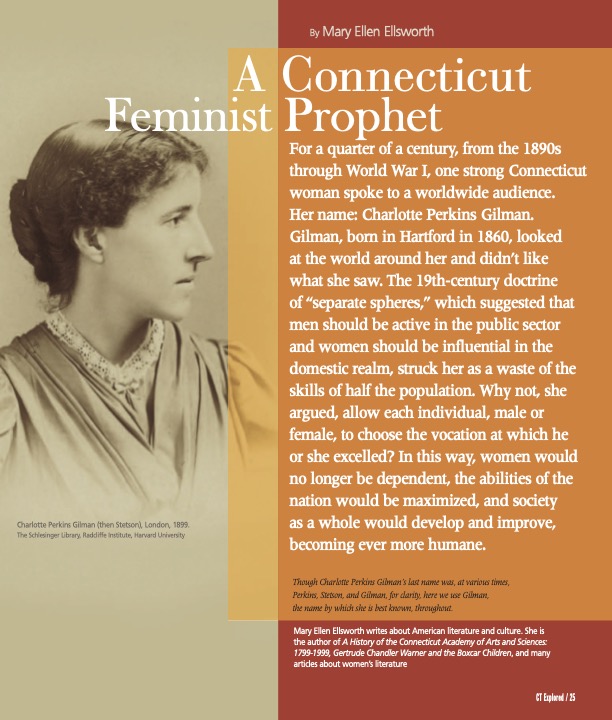

Charlotte Perkins Gilman (then Stetson), London, 1899. The Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University

By Mary Ellen Ellsworth

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Winter 2011-2012

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

Note: Though Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s last name was, at various times, Perkins, Stetson, and Gilman, for clarity, here we use Gilman, the name by which she is best known, throughout.

For a quarter of a century, from the 1890s through World War I, one strong Connecticut woman spoke to a worldwide audience. Her name: Charlotte Perkins Gilman. Gilman, born in Hartford in 1860, looked at the world around her and didn’t like what she saw. The 19th-century doctrine of “separate spheres,” which suggested that men should be active in the public sector and women should be influential in the domestic realm, struck her as a waste of the skills of half the population. Why not, she argued, allow each individual, male or female, to choose the vocation at which he or she excelled? In this way, women would no longer be dependent, the abilities of the nation would be maximized, and society as a whole would develop and improve, becoming ever more humane. Women’s suffrage leader Carrie Chapman Catt described Gilman as “the most original and challenging mind … the (women’s) movement produced.”

Gilman was born Charlotte Anna Perkins in Hartford on July 3, 1860, to Frederick Beecher Perkins and Mary Fitch Wescott Perkins, both members of prominent families. Her great grandfather was Lyman Beecher, temperance leader and first president of Lane Theological Seminary; her great uncle, Henry Ward Beecher, the famed theologian. Her great aunts included Catharine Beecher, founder of the Hartford Female Seminary, Isabella Beecher Hooker of suffragist fame, and Harriet Beecher Stowe, whose Uncle Tom’s Cabin was the most popular book in 19th-century America, outside of the Bible.

Gilman’s father left when she was quite young, and her mother, though remaining in contact with the Hartford relatives, raised Charlotte and her brother on her own. Constant moves, dictated by financial insecurity, meant that young Charlotte had a sporadic, incomplete education: “my total schooling covered four years, among seven different schools, ending when I was fifteen,” she says in her autobiography, The Living of Charlotte Perkins Gilman. After that, she studied for two years at the newly established Rhode Island School of Design. Her greatest growth, though, was internal. At 17 she wrote to her father, a respected librarian, then at the Boston Public Library, telling him that she wished “to help humanity” and that, since she must understand history to do so, she wished his suggestions for texts. “The first duty of a human being,” she observed, “is … to find your real job, and do it.”

At 21, Charlotte met Charles Walter Stetson, a painter possessing a “noble soul,” and wrestled with his quickly proffered marriage proposal. As she put it, “I felt . . . that I ought to forego the more intimate personal happiness for complete devotion to my work”; “from sixteen I had not wavered from that desire to help humanity which underlay all my studies.” However, marry she did, in 1884, and she noted, “We were really very happy together.” Within a year they had “an exquisite baby,” Katharine.

But Gilman soon became despondent. She visited Dr. S. Weir Mitchell of Philadelphia, to treat what was labeled “hysteria.” She tried to follow his prescription for a domestic life void of intellectual thought. Her depression worsened, and she and Stetson agreed to separate in spite of their mutual affection and respect for one another.

In fall 1888 Gilman left for California with her daughter, her good friend Grace Channing, and a caretaker for Katharine. She began writing articles and poetry for publication and in 1890 wrote the short story “The Yellow Wallpaper.” She based the fictional piece on her personal experience of what we now know as post- partum depression and the challenges of domestic life. The story, published in 1892 in the New England Magazine, was written, she said, “to reach Dr. S Weir Mitchell, and convince him of the error of his ways.” She was pleased when she heard that the doctor had changed his prescriptions. In 1890 Gilman was asked to speak before Pasadena’s Nationalist Club, a group inspired by Edward Bellamy’s 1888 utopian novel Looking Backward, which advocated economic equality and national socialism. She found she enjoyed lecturing: “I had plenty to say and the Beecher faculty for saying it.”

In 1890 Gilman was asked to speak before Pasadena’s Nationalist Club, a group inspired by Edward Bellamy’s 1888 utopian novel Looking Backward, which advocated economic equality and national socialism. She found she enjoyed lecturing: “I had plenty to say and the Beecher faculty for saying it.”

In 1893 Gilman published a small book of poems, In This Our World. The poems, expressing her optimism, were didactic lessons on her favorite topics: women, the roles of wives and mothers, and labor. The book fueled her British acclaim, providing her “a far higher reputation” in England than at home.

Her divorce was granted, finally, in April 1894. Gilman moved to San Francisco, sending her daughter east to live with Stetson, who had married her friend Grace Channing. Gilman lived frugally, supporting herself by organizing annual women’s congresses and speaking and writing. She felt beleaguered and maligned, both for her divorce and for “abandoning” her child. “I had put in five years of most earnest work with voice and pen, and registered complete failure.” In her autobiography she noted, “I had warm personal friends, to be sure, but the public verdict was utter condemnation.” Her personal evaluation was also severe: “Thirty-five years old. A failure, a repeated, cumulative failure. Debt, quite a lot of it. No means of paying, no strength to hold a job if I got one.” Gilman was to be, as she put it, “at large” from 1895 until 1900, with no permanent home. She traveled with a couple of suitcases, finding lodging near her speaking engagements, writing always.

On July 10, 1896, Gilman sailed for England to attend the International Socialist and Trade Union Congress. The Congress drew 782 delegates, more than half from Britain, and a significant number from France and Germany. The United States sent seven members, including Gilman. Since she did not endorse the socialists’ support of class warfare and violence, Gilman represented the Alameda County California Federation of Trades.

The Fabian Society, an English group seeking democratic socialism through gradual reforms, made Gilman a member; through this connection she met prominent people such as George Bernard Shaw and William Morris. A “Great Peace Demonstration” in Hyde Park preceded the event’s opening in Queen’s Hall, Central London.

After the conference, Gilman stayed on. “[B]ack and forth I went, … for lectures and visits.” She “spoke often; in halls and drawing-rooms, once on London Docks standing on a chair in the rain, in Liverpool, in the market-place in Shields, in Newcastle.” In Glasgow, Lily Bell, a columnist for The Labour Leader, labeled her a speaker “peculiarly qualified for imparting her knowledge to others, … putting her subject before her hearers in a manner which renders it both attractive and acceptable.” Gilman returned to New York in November 1896.

Gilman was, at this time, “[f]ull of the passion for world improvement, and seeing the position of women as responsible for much, very much, of our evil condition.” Gilman argued that the political equality demanded by the suffragists was not enough. “Women whose industrial position is that of a house-servant, or who do no work at all, who are fed, clothed, and given pocket-money by men, do not reach freedom and equality by the use of the ballot.” In fall 1897 Gilman completed the first draft of Women and Economics in just 17 days. Published the next year, it expressed the culmination of her thinking and teaching.

Gilman sailed to London on May 4, 1899 to attend the third Congress of the International Council of Women. “[L]eading women [came]… together from all parts of the world and learned to know each other and their common needs.” It was an amazing gathering—some 3,000 women were in attendance. Gilman, a free-lance representative, joined U.S. suffragists Susan B. Anthony and Anna Howard Shaw. Though she gave only one prepared talk, “Equal Pay for Equal Work,” and Women and Economics had not yet been published in England, Gilman was a celebrity. There was a “waiting list” for her new book, and “long, respectful reviews” appeared in the papers. “What with my former reputation, based on the poems, this new and impressive book, and my addresses at the Congress and elsewhere,” Gilman said, “I became quite a lion.”

Women and Economics “sold and sold and sold for about twenty-five years,” Gilman reported. It was translated into French, German, Dutch, Italian, Hungarian, Japanese, and Russian; Putnam’s released a seventh British edition in 1911. While Gilman never realized much profit from it, her lecturing fees increased, and she appeared in publications such as Cosmopolitan and The Saturday Evening Post. Never one to see herself in a small way, she labeled herself a “humanitarian prophet,” and when her book Human Work, published in 1904, did not seem to make any impression, she noted, “Neither did the work of Mendel, for some time.”

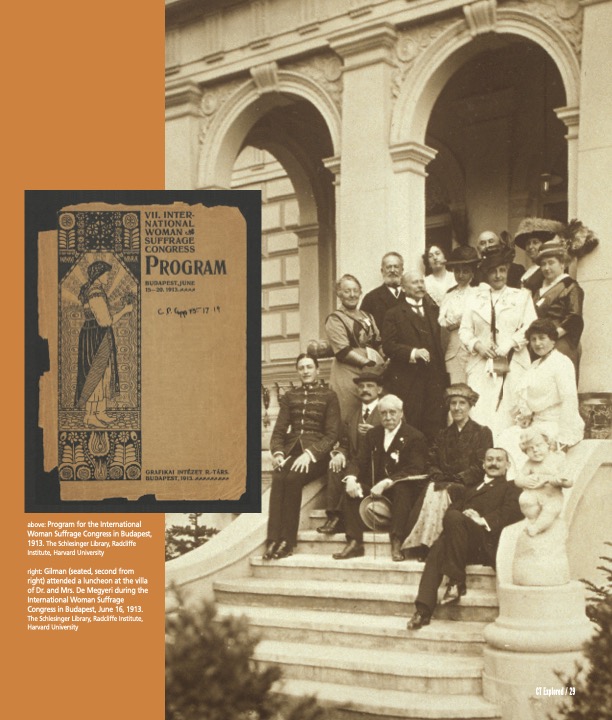

left: Program for the International Woman Suffrage Congress in Budapest, 1913. The Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University right: Gilman (seated, second from right) attended a luncheon at the villa of Dr. and Mrs. De Megyeri during the International Woman Suffrage Congress in Budapest, June 16, 1913. The Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University

The 20th century dawned happily with her marriage to her first cousin and great friend Houghton Gilman in June 1900. The Gilmans took an apartment in New York City; they received their meals nearby, and Charlotte had what she wanted: “a home without a kitchen, all the privacy and comfort, none of the work and care.”

The success of Women and Economics in its German translation made Gilman a natural for the next Congress of the International Council of Women, held in Berlin in 1904. “Not even in London in 1899 did I have such an ovation,” she noted. She had tried to learn German, without success, and so her speeches were in English. In spite of that, “so popular was I that great crowds followed me from one hall to another.” One admirer, Marie Lamping, sent her a hand-written note dated June 17, 1904, expressing the sentiments of many: “Believe me, you have touched the right chord in our hearts that will vibrate long after you have gone.” Gilman and 3,000 other foreign women were feted: the American ambassador gave a reception, and the city fathers of Berlin hosted a banquet.

Gilman immediately planned another European lecture tour; in February 1905 she was off again. Harry Beswick, a columnist in Manchester, England, described her podium manner: “When she is making a good point … there is a delightful little chuckle in her voice which is absolutely infectious. [A]s a lecturer [she]is fluent, epigrammatic, logical, humorous, and exceedingly interesting. Her talk is ‘full of meat.’” He added: “I don’t think I ever heard any public man say so much in an hour, or say it so well.” She traveled to Holland, where both Women and Economics and her Concerning Children (1900) had been translated into Dutch, and to Germany, Austria, and Hungary.

From 1909 to 1916, Gilman wrote and published her own magazine, The Forerunner. It was a heroic undertaking. She wrote poetry, short stories, columns, and critical pieces and edited, published, and promoted the 21,000-word monthly, whose circulation of about 1,500 was inadequate to cover the $3,000 it cost to publish each year. Three of her utopian novels, including Herland, were serialized in The Forerunner. Herland (1915) takes a young, male narrator to a new territory, a land inhabited only by women. The women, no longer imprisoned in isolating marriages and circumscribed homes, have both privacy and companionship as they work together. Nurturers of the young and the bearers of the cultural values of love and cooperation, the women are the resources for a new social vision. The novel, funny and light, is also a serious polemic.

In 1913 Gilman traveled to Europe once more, to Budapest, Hungary, for the International Woman Suffrage Congress. Women and Economics had been translated into Hungarian, and in a July 20, 1912 invitation to attend, the executive committee wrote: “we [cannot]imagine our victory without having you here on the Congress. Your name, your personality, your work are so wellknown [sic]in Hungary and are taken for so valuable, that your absence would cool all the interest people show towards the Congress.” She lectured in England, Germany, and Scandinavia before and after the conference to help pay The Forerunner bills, which came to $1,500 a year more than the subscriptions and ads covered.

In 1922, Charlotte and Houghton moved to the Gilman family home in Norwich, Connecticut, where they lived until his death in 1934. There she found, as she said in her autobiography “dignity and beauty and peace,” adding, “I enjoy it with the delight of a returned exile.”

In her later years, Gilman continued to lecture occasionally until, she said, demand weakened, overtaken by “the advance of the radio.” Gilman felt disappointed that socialism was still misunderstood and misrepresented by Marxism and Bolshevism. She also saw little progress in “domestic industry. Nonetheless, a number of the goals she had worked for had been achieved, including, for women, full suffrage and advances in education, business, and the professions. The labor movement had garnered higher wages, shorter hours, and better working conditions.

On August 17, 1935, suffering from inoperable breast cancer, Gilman committed suicide, noting in the letter she left at her death, “I have preferred chloroform to cancer.”

Mary Ellen Ellsworth writes about American literature and culture. She is the author of A History of the Connecticut Academy of Arts and Sciences: 1799-1999, Gertrude Chandler Warner and the Boxcar Children, and many articles about women’s literature.

Explore!

Read more stories about Notable Connecticans on our TOPICS page

Read more stories about Connecticut’s art and literary history on our TOPICS page

Read more about Women’s Suffrage on our TOPICS page

Read Fall 2014: The Power of the Pen