(c) Connecticut Explored Inc, Summer 2020

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

“Educate the Girls, Says Mrs. Livermore,” ran the August 30, 1899 Waterbury Evening Democrat headline. The story reported on the principles of Boston suffragist Mary Livermore, who promoted education as the path to women’s independence. Livermore was preaching to the choir, since Waterbury had, since 1824, made strenuous efforts to provide high schools for both boys and girls, including one established specifically for girls in 1869.

As the city’s population grew in the years before the Civil War, so did a rising and prosperous middle class. In response, city leaders, including Frederick J. Kingsbury and Augustus S. Chase, determined to organize a school that offered “a wider, higher, stronger, more liberal education for young women: and this not only for the very wealthy few who can pay for it in distant, costly schools but such an education for a much larger portion of our daughters,” as Carol Burke Ohmann recorded in Saint Margaret’s School: 1865 – 1965 (Saint Margaret’s Alumnae Association, 1965).” Thus was born Waterbury’s Collegiate Institute, opened in 1869 and restructured in 1875 as Saint Margaret’s School. Girls and young women at the school, announced an undated promotional brochure in the school archives, were prepared there for “constructive living in a world undergoing constant change.”

Saint Margaret’s students emerged accomplished, industrious, and socially conscious, as the 1914 – 1915 edition of Woman’s Who’s Who of America suggests. Eleven of the 16 women from Waterbury listed were Saint Margaret’s School graduates. In preparing the volume, editor John Leonard saw the suffrage question “looming conspicuously above the horizon of public interest,” so he sent data sheets to all 16 Waterbury women who were to be listed asking their stand on women’s suffrage. Among the respondents, 12 favored suffrage, 3 did not reveal their stand, and 1 was against. The woman who was against suffrage was Elizabeth Hosmer Chase, the wife of Irving Hall Chase, a son of Saint Margaret’s founder Augustus S. Chase.

Among those reporting that they supported women’s suffrage was Lucy Woodward Vauthier, a Saint Margaret’s graduate. After graduating from Wellesley College in 1902, Woodward returned to Connecticut and married Leon Vauthier, a graduate of Yale Divinity School. She lectured before college groups and Daughters of the American Revolution chapters in Connecticut and Massachusetts on subjects including pure food, child labor, and equal rights for women.

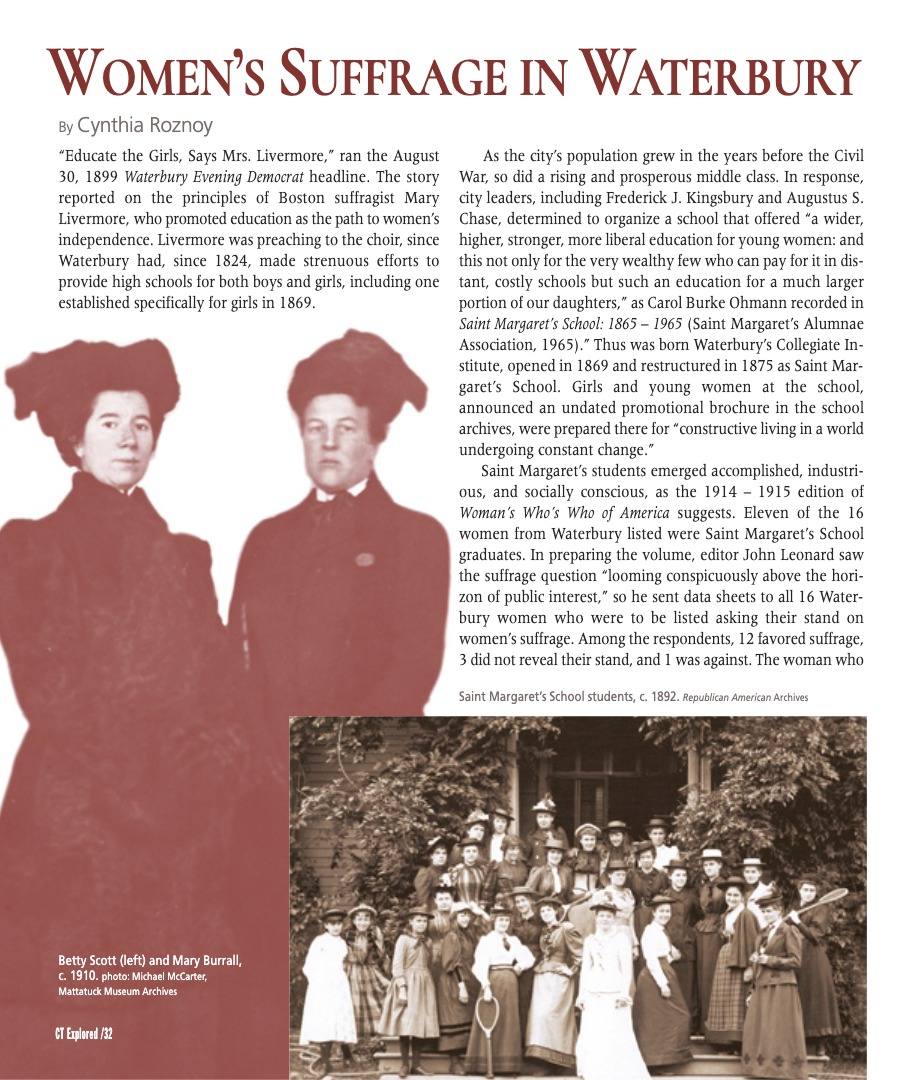

Another was Betty Scott. She studied vocal music in Europe after also attending Wellesley. Upon her return to Waterbury in late 1909, she quickly became active in the suffrage movement, assuming a leadership position in 1910 as chair of the publicity committee of the Waterbury chapter of the Connecticut Equal Suffrage League, Woman’s Who’s Who of America noted. She was invited to share the home of Lucy and Mary Burrall, sisters who were her schoolmates at Saint Margaret’s.

Archives at the Mattatuck Museum tell the life story of Mary and Lucy Burrall. The sisters were life-long companions with their Church Street neighbor Edith Chase (the granddaughter of Augustus Chase), and Scott was welcomed into their congenial group, as photographs in albums suggest. The Burrall sisters were financially independent, and their solid educations went far in providing a self-confidence that inspired liberation. The Burralls’ scrapbooks, filled with newspaper clippings, indicate that suffrage was likely a topic of discussion among them, and some of those discussions may have been instigated by Scott’s reports of her activism.

In Waterbury, the Saint Margaret’s graduates were representative of women’s suffrage leadership that was typically drawn from the wealthy middle and upper middle class, according to Ohmann. For the most part, these women’s progressive work was aligned with acceptable social-class activities, but it also addressed social issues such as child labor and fair work standards. In an article titled “Political Equality” published on May 1, 1894, the Waterbury Evening Democrat described the joining of “the society woman with the advanced woman in calling for practical equality of the sexes.” Prominent Waterbury women including Susan C. O’Neill, the first woman to practice law in Connecticut, and historian of Native American life Constance G. Dubois joined Florentine Hayden, Ann Lydia Ward, Vauthier, and others to foster supports leading to self-development of the city’s women.

Anna Lydia Ward is another example of female leadership in the city. From the time she came to Waterbury in 1887, Ward was connected with city interests and women’s advancement. The daughter of a New York City businessman, she was a world traveler, lecturer, writer, community activist, and a role model for women seeking an independent life. In 1886, at age 40, she traveled with her companion Florentine Hayden to Labrador and Newfoundland, farther north than any other American woman to that date. Their travels were documented by the Smithsonian Institution in its 1888 Annual Report. Ward’s lectures about her interactions with the Inuit were advertised in Waterbury’s April 1, 1892 Daily American and New York’s June 1894 Everett House Newsletter. Ward’s writing career gained a boost of celebrity as booksellers promoted her travel accounts in national catalogues such as The Bookmart. Hayden recalled in her self-published Anna Lydia Ward: A Remembrance (1933) that Ward, with fellow Waterburian Sarah Pritchard, was an associate editor of the three-volume history The Town and City of Waterbury, Connecticut (1896) compiled by Joseph Anderson.

Census records, city directories, and photographs in the Mattatuck archives show that Ward and Hayden lived together in a stylish home on Pine Street. Brought together by shared interests in art and literature, they also were united by their concerns in civic affairs. Ward, in particular, linked the world of club activity and working women with her philanthropic labors. A letter from a “Mrs. A.R.K.” quoted in Anna Lydia Ward describes Ward’s “constructive and devoted service which helped girls become better women and finer citizens of Waterbury.”

Ward was appointed to the Advisory Commission for Appointment of Female Deputy Factory Inspector, created by Governor Rollin Woodruff, on which she served from 1907 to 1915. In 1909 Ward testified before the Connecticut Bureau of Labor Statistics (now the Connecticut Department of Labor) about industrial training for girls. For more than 25 years, she was president of the Waterbury Institute of Craft and Industry founded in 1889 (called the Young Women’s Friendly League until 1908) and served on its executive committee. Ward and Hayden played a significant role in the development of the women’s clubs and social-welfare programs that moved Waterbury into the Progressive Era.

From its founding in 1889, according to The Town and City of Waterbury, the Young Women’s Friendly League took as its mission vocational training for girls and young women, particularly those already at work in factories and shops. League classes were offered in reading, arithmetic, typewriting, history, music, millinery, and dressmaking. The goal of the organization was to give wage-earners greater control over their lives in the way the labor and voting-rights movements sought to do. The hoped-for trajectory, as Ward stated in “A Review of 1898 by President Miss Anna L. Ward” in the Waterbury Evening Democrat (February 3, 1899), was economic security, self-sufficiency, and then political equality.

In the Progressive Era, Waterbury was home to women’s clubs of all varieties. If you were a Waterbury woman seeking to expand your history and literary horizons, you joined the Tuesday Club, established in 1894, with like-minded friends including Helen Platt Camp, Helen Sperry, and Laura White—all from prominent Waterbury families. Topics in the 1910s, as recorded in meeting minutes, focused on the history and art of Russia, Italy, and Japan, for example. Meetings also turned to social subjects, among them “The Family,” “Evolution of Marriage,” and “World War I.” The May 2, 1916 meeting offered a discussion of Porter Emerson Brown’s article in McClure’s magazine in favor of pacifism; later that year, the September 1916 McCall’s article “What Women Want,” a feminist-positive essay, was the topic of discussion. It would be another three years, though, before women’s rights were brought up again for discussion. The meeting minutes for November 18, 1919 indicate a circular about voting rights was shared that was, as the minutes recorded, “endeavoring to arouse an interest [in suffrage]among the women of Waterbury, especially in the women’s clubs.” This suggests a shift in discourse among some Waterbury club women who may have been resistant to suffrage and documents the strides the movement had made in the city during the decade.

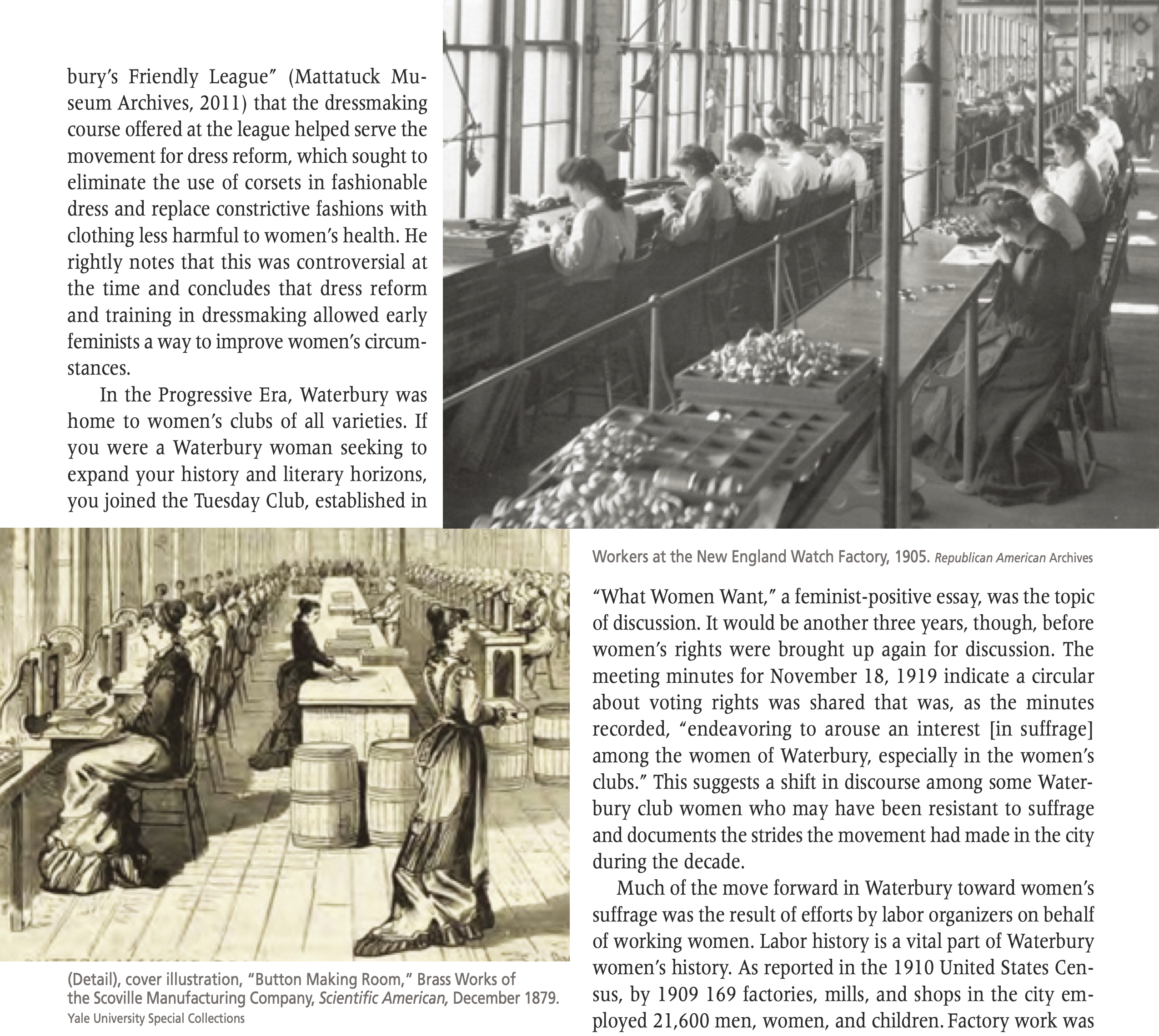

Much of the move forward in Waterbury toward women’s suffrage was the result of efforts by labor organizers on behalf of working women. Labor history is a vital part of Waterbury women’s history. As reported in the 1910 United States Census, by 1909 169 factories, mills, and shops in the city employed 21,600 men, women, and children. Factory work was well established. Thirty years earlier, the cover of Scientific American (December 1879) featured various workrooms in Waterbury’s Scovill Manufacturing Company. One illustration portrayed the button-making room in which dozens of women are at work, seated before their stamping machines. Factory work, however exhausting, dirty, or unhealthy, provided new paths for women toward independence.

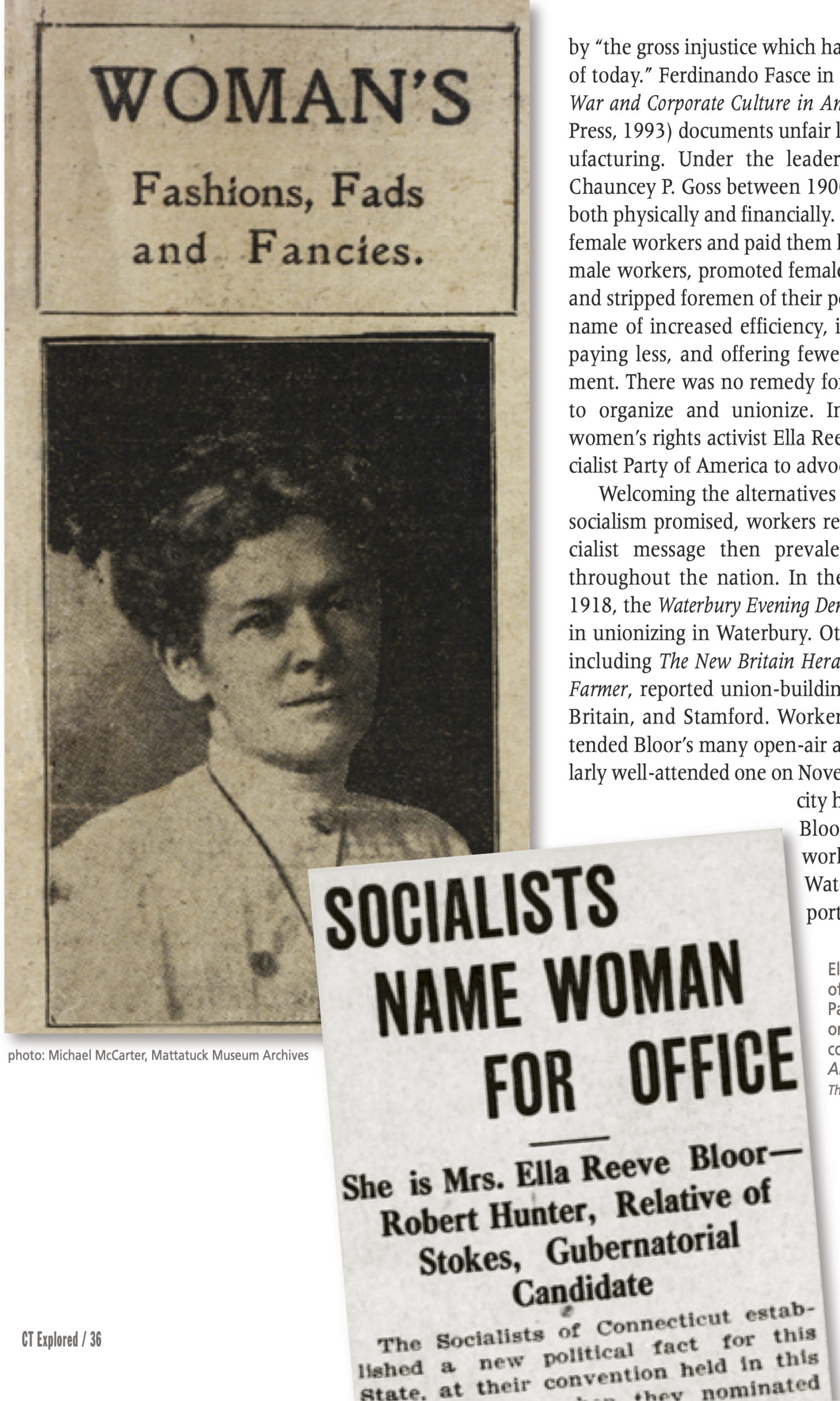

But inequality in the workplace was widespread and, as described in the Waterbury Democrat (May 21, 1894) tainted by “the gross injustice which has been done the workingman of today.” Ferdinando Fasce in An American Family: The Great War and Corporate Culture in America (Ohio State University Press, 1993) documents unfair labor practices at Scovill Manufacturing. Under the leadership of company president Chauncey P. Goss between 1900 and 1918, Scovill expanded both physically and financially. Goss increased the number of female workers and paid them lower wages than comparable male workers, promoted female plant workers to office jobs, and stripped foremen of their power on the plant floor in the name of increased efficiency, including by reducing hours, paying less, and offering fewer opportunities for advancement. There was no remedy for this, many workers felt, but to organize and unionize. In 1905 labor reformer and women’s rights activist Ella Reeve Bloor was sent by the Socialist Party of America to advocate on their behalf.

But inequality in the workplace was widespread and, as described in the Waterbury Democrat (May 21, 1894) tainted by “the gross injustice which has been done the workingman of today.” Ferdinando Fasce in An American Family: The Great War and Corporate Culture in America (Ohio State University Press, 1993) documents unfair labor practices at Scovill Manufacturing. Under the leadership of company president Chauncey P. Goss between 1900 and 1918, Scovill expanded both physically and financially. Goss increased the number of female workers and paid them lower wages than comparable male workers, promoted female plant workers to office jobs, and stripped foremen of their power on the plant floor in the name of increased efficiency, including by reducing hours, paying less, and offering fewer opportunities for advancement. There was no remedy for this, many workers felt, but to organize and unionize. In 1905 labor reformer and women’s rights activist Ella Reeve Bloor was sent by the Socialist Party of America to advocate on their behalf.

Welcoming the alternatives to workplace oppression that socialism promised, workers responded positively to the socialist message then prevalent in manufacturing cities throughout the nation. In the decade between 1907 and 1918, the Waterbury Evening Democrat reported developments in unionizing in Waterbury. Other Connecticut newspapers, including The New Britain Herald and The Bridgeport Evening Farmer, reported union-building in Hartford, Meriden, New Britain, and Stamford. Workers, the Democrat reported, attended Bloor’s many open-air addresses, including a particularly well-attended one on November 14, 1907 at Waterbury’s city hall. During the next five years Bloor spoke eloquently about workers’ and women’s rights in Waterbury, as the Democrat reported.

top: Mattatuck Museum Archives, bottom: Ella Reeve Bloor ran for secretary of the state in 1910 on the Socialist Party ticket. She was a labor organizer and Woman’s Pages columnist at the Waterbury American, 1908 – 1911. The Bridgeport Evening Farmer

Bloor’s life story reflected the changing definitions and structure of family life just emerging in the early years of the 20th century. Born into the middle class in Staten Island, New York, Bloor was married three times, was a head of household and single mother of six, and worked outside her home, often traveling great distances. She identified as a member of the working class, and she was always concerned with the problems of working-class mothers. Her consciousness of both suffrage and workers’ conditions began early in her life. In her autobiography, We Are Many(International Publishers, 1940), she revealed, “Through the Quakers, who believe in equality for women, I first came into touch with the woman suffrage movement.”

As the October 30, 1907 meeting minutes of the Connecticut Woman Suffrage Association (CWSA) recorded, Bloor found no active suffrage organization in Waterbury when she arrived in 1905, and she set about to establish one. Unfortunately, she had little success. In We Are Many, she noted that “for many of the secure middle class ladies the suffrage movement was a mere feminist fad” and “it was only through the participation of Socialist women, that the suffrage movement in general became awakened to the problems of working women.” Her efforts were also recorded in the minutes of CWSA meetings—an organization that, itself, would, starting in 1910, experience a rebirth and rejuvenation, including in Waterbury as Betty Scott’s involvement suggests. Bloor’s efforts were also recorded in regional newspapers, including the Waterbury American, where Bloor was a columnist beginning in 1908.

In 1910 Bloor ran for Connecticut secretary of the state on the socialist ticket. Her nomination was the first for a woman for state office in Connecticut. She didn’t win, and that disappointment was one of two in 1911 that changed the course of her career. Bloor explained in We Are the Many that her speech on “The Cause and Cure of Child Labor” that year got her fired from the Waterbury American because of its provocative subject. She was invited to stay, she said, on the condition that she “renounce her political faith.” Instead Bloor left Waterbury that year to organize mine workers in Pennsylvania.

Despite Bloor’s setbacks, the city Bloor departed in 1911 had made meaningful strides on its path to suffrage, moving slowly as it built on past achievements. Women had gained the right to vote on the city’s educational issues via a state law passed in Connecticut in 1893. The 1899 Official List of Women Voters in Waterbury (now in the state archives) named 282 women from diverse backgrounds: teachers, factory laborers, housekeepers, almshouse matrons, and wives “keeping home” among them.

But the press in Waterbury did not throw its support behind the cause. Waterbury women had the opportunity to hear art collector and heiress Louisine Havemeyer speak about suffrage on January 21, 1915. Havemeyer biographer Alice Cooney Frelinghuysen, in Splendid Legacy: The Havemeyer Collection (Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1993), documents the speech as the first of many Havemeyer delivered in Connecticut, New York, and New Jersey to rally support for the cause. Impressionist artist Mary Cassatt had inspired Havemeyer’s activism and had brought her together with women’s-rights supporter Theodate Pope, the architect of Hill-Stead in Farmington (now Hill-Stead Museum), and the philanthropist Harris Whittemore of Naugatuck. But Havemeyer’s appearance in Waterbury was neither announced in the local newspapers in advance nor reported on afterward, so her effect on Waterbury women is unknown. Though efforts and engagement continued through 1919, Waterbury newspapers made little note of the ratification effort across the 48 states. The city reflected Connecticut’s strategy of delay. By the time Connecticut representatives met for the vote on September 14, 1920, the 19th Amendment was officially part of the U.S. Constitution. [See “The Long Road to Women’s Suffrage,” Spring 2016.]

Generally, there was a growing acceptance of women’s rights during the World War I era and a begrudging recognition of women’s expanding roles outside the domestic sphere. Minds changed when women proved proficient in shouldering the home-front burdens of World War I. Young women in Waterbury pushed the fight for suffrage, as observations recorded in Saint Margaret’s School yearbooks reveal, including Gertrude Deming’s in 1916 about a friend who “told me of what a busy life she was leading—suffrage [marches]and the like.”

Women’s activism took many paths in Waterbury, and socio-economic class was a critical factor in determining the road taken. Educational and social organizations founded and led by upper-class women were active in trying to move women of all classes toward equality. But the efforts of labor organizers were important, too. Stories of private and institutional accomplishments encompass the range of dramatic and popular campaigns for enfranchisement of Waterbury’s women.

Cynthia Roznoy is curator at the Mattatuck Museum. She is organizing A Face Like Mine: Figuration in 20th-Century African American Art for the opening of the renovated museum planned for Spring 2021.

Explore!

Read all of our stories about Women’s Suffrage on our TOPICS page.