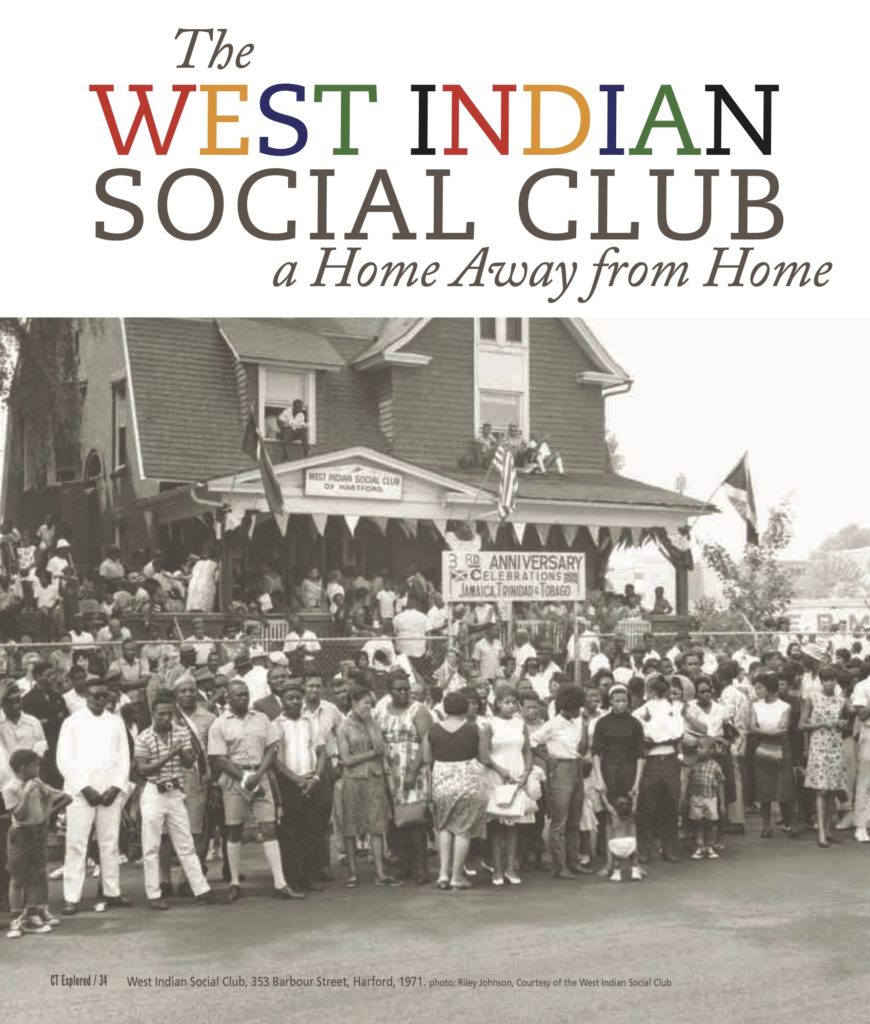

West Indian Social Club, 353 Barbour Street, Harford, 1971. photo: Riley Johnson, Courtesy of the West Indian Social Club

By Fiona Vernal

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Summer 2022

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

According to its founding charter, The West Indian Social Club of Hartford (WISC) will celebrate its 72nd anniversary in October 2022. One of the longest-running and continuous Caribbean social organizations in the United States, the club was founded by West Indian migrant farm workers in 1950. For seven decades the WISC has been the pulse of Hartford’s burgeoning Caribbean community.

For its first 20 years, the club operated at 353 Barbour Street, a multi-family home renovated to accommodate a bar and dance floor. As the club expanded its social, economic, and political activism, in 1974 the WISC relocated to its present site at 3340 Main Street, formerly the Hartford Skating Palace. The history of the club captures some of the ways Caribbean diasporic communities tether themselves to the United States while trying to maintain their cultural heritage. The origin story of this important pillar of the Caribbean community in the vision of West Indian farm workers is deeply embedded in the history of Connecticut’s boutique shade tobacco industry.

Connecticut’s shade tobacco industry, which provides wrappers for cigars, faced a significant labor crisis with the outbreak of World War II. Meanwhile, Caribbean communities, barely recovered from Depression-era economic woes and labor unrest, suffered from a halt in tourism and disruption of agricultural trade. These conditions ushered in new opportunities for West Indian men to work in agriculture in the mainland U.S. via the British West Indies Temporary Alien Labor Program, an emergency measure in effect from 1943 to 1947. Never able to compete directly with West Coast growers, a network of farmers from the Northeast, Midwest, and the South teamed up to continue this seasonal guest worker program at the end of the war. Tobacco growers were particularly vocal in lobbying the U.S. Congress. As a result, West Indian labor became a mainstay in the apple, sugarcane, and shade tobacco industries, according to a 1951 study for the U.S. Senate Committee on the Judiciary.

Connecticut’s tobacco fields and sheds were crucial spaces where African Americans, Puerto Ricans, and West Indians got to know each other better and establish new social networks. The West Indian guest workers encountered African American and Puerto Rican women who worked in tobacco, sewing the leaves together. [See “Tobacco Valley: Puerto Rican Farm Workers in Connecticut,” Fall 2002.] In their off time, West Indian men had opportunities for social, athletic, and religious excursions to Hartford, New York, and Boston. African American youth and adults, like the future Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., who were also recruited to help address labor shortages, shared similar experiences. [See “Laboring in the Shade,” Summer 2011.] These encounters served as a kind of reconnaissance mission whereby West Indian men found out about jobs, housing, and congregations that matched their religious affiliations. Some West Indian guest workers married African-American women. They gained an important toehold in the local African American community and formed a nascent West Indian community in Hartford’s North End.

The West Indian Social Club was born in 1950 from the vision of this first generation of West Indian farm workers. People met in the homes of their friends and colleagues and later in St. Monica’s Episcopal Church on Main Street. In 37 interviews I conducted for the West Indian Community History Project archived at the Connecticut Historical Society, members recounted how they pooled their resources to charter the club. John Richardson was the organization’s first president, followed in quick succession by David Mills. Those I interviewed acknowledged little interest in subordinating their cultural heritage to participate in assimilationist rhetoric that rang hollow. They believed they could maintain their culture while taking advantage of the economic opportunities the U.S. had to offer. While the vast majority of men went back home after the war, those who married American citizens, or found workarounds to secure permanent residency, stayed. They encountered white people who rebuffed their attempts to patronize local bars or obtain information about permanent residency.

For West Indians and African Americans alike, Hartford’s housing supply in the North End was limited and the quality was often poor. They yearned for autonomous spaces with a welcoming social atmosphere. This was not only in reaction to American-style racism, social isolation, or restrictive living conditions. West Indians also brought with them a rich heritage of social, fraternal, and religious organizing that inspired the desire for both autonomy and cultural belonging in Hartford.

The West Indian Social Club’s meetings began long before they had their own physical space. Early membership cards are dated January 1950, while membership minutes from February 5, 1950 show 21 members were added to the previous total of 25. Once the Barbour Street multifamily property was purchased and renovated in the early 1950s, all manner of social, economic, and political activities unfolded there. In addition to its role as a social space for people to gather, it fostered a grapevine that could lead to a job and became the site for collecting disaster aid when hurricanes hit the Caribbean. If you wanted to play dominoes or join a cricket team, this was the place to connect. In fact, cricket was never far from the agenda, with $53 collected at the August 1950 meeting to purchase cricket gear. [See “Cricket Comes to Hartford,” Spring 2003.] West Indians gathered at the club for major life events to celebrate and mourn. Whether birth, marriage, or death, the club was a site for numerous baby showers, repasts, weddings, birthdays, retirements, and anniversaries. Some people partied there regularly or saved their merry-making for West Indian Week celebrations that began with Jamaica’s independence in 1962. Annual parades commemorated this important step in achieving Caribbean political sovereignty, and pageants brought hundreds of people into the club. Successive presidents and members of this organization hosted local political candidates, dignitaries, and entertainers from the Caribbean.

Membership was only open to men. After several years of heated debate about the terms of women’s participation, the matter was settled, as the May 30, 1953 minutes recorded. The Ladies Auxiliary was created in 1954 with Connie Mills as its first president. The early Ladies Auxiliary was composed of West Indian women and the American wives of members. Women worked hard and arranged many social functions such as teas, talent shows, trips, dances, game days, dinners, and beauty pageants, all of which brought revenue into the club.

West Indian Social Club Women’s Auxiliary members participate in West Indian independence celebrations. Courtesy of the West Indian Social Club

The women continued to voice their concerns about their second-class status in light of their hard work at numerous fundraising events. While many members opposed the full integration of women, those who favored the measure finally prevailed in 1980. The auxiliary was dissolved, and women became full members of the club. By 1989 the WISC was led by former Hartford Councilwoman Honorable Veronica Airey-Wilson as its first female president. She was followed by other women who served as president, including Dr. Alred Dyce, Doreth Flowers, Doreen Forest, Marva Wilks, and attorney Nicone Gordon. Beverly Redd was installed in the new position of Chairwoman in January 2022.

The pioneering efforts of the West Indian Social Club and the transition to Caribbean independence throughout the 1960s paved the way for many other Caribbean organizations in Hartford. The Caribbean American Society was founded in 1957, its name a recognition of the dual heritage of American and West Indian families comprising the growing community. The Barbados American Society, the Trinidad & Tobago American Society, the Jamaica Progressive League, Sportmen’s Athletic Club, the West Indian Foundation, the Cricket Hall of Fame, the Jamaica Ex Police Association, the Caribbean Ladies Cultural Club, the St. Lucia American Society, and the Guyanese American Cultural Association are among the other organizations chartered as the number of Caribbean migrants to the Greater Hartford region grew.

The rapid growth in the Caribbean population stemmed, in part, from the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, which eliminated quotas restricting immigration from the Caribbean. The Reagan-era Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986 gave a further boost to the possibility of family reunification. With these two laws, Caribbean women could now emigrate independently and take advantage of economic opportunities available to them. Married women and children could join the other parent.

By 2010 reforms to immigration policies and family reunification made the Greater Hartford area a major destination for Caribbean migrants. Jamaicans predominated because Jamaica is the closest and largest English-speaking Caribbean nation to the U.S. Working shade tobacco was the initial entry point for many in Connecticut, but employment, entrepreneurship, and homeownership drew and kept people rooted in the area. The largest proportion of West Indians still live in Hartford, with a growing population in the local suburban ring towns of Windsor and Bloomfield. According to the 2010 census, West Indians became the largest foreign-born population in Connecticut. This is significant for a small state like Connecticut because the proportion of West Indians in the capital region gives them an important voice in local politics.

The West Indian Social Club continues to play a critical role in the evolution of the Caribbean community. Its founding fathers started a tradition that speaks volumes to their vision of belonging, inclusion, and place-making. They navigated and overcame their own struggles with gender equality. In its 72 years WISC has remained “a home away from home” and continues to host Caribbean entertainers and dignitaries. Every generation connects to the space and creates its own memories. And it evolves with the times. More recently WISC has hosted COVID-19 vaccinations and Red Cross blood drives. It also became a resource for parents bewildered by Google Classroom or needing WiFi access to learn how to close the digital divide.

New organizations continue to sprout in the Caribbean community, including dance troupes, soccer leagues, and the Hartford St. Lucia Lions Club. The WISC stands apart as the mother organization, the progenitor and keeper of the legacy of a generation of founders who were willing to try their hand at agriculture no matter what their actual class background or experience. They were willing to sacrifice for the greater good of their families and their communities. When they transitioned from the farms, they forged a very Caribbean version of the American dream, replete with a house, a good job, grand educational aspirations, and a foothold in the American political machinery. They not only created an autonomous social space, they made Hartford a Caribbean city.

Dr. Fiona Vernal is the director of Engaged, Public, Oral, and Community Histories (EPOCH) and Associate Professor of History and Africana Studies at the University of Connecticut.

This is one in a series of stories funded in part by Hartford Foundation for Public Giving about the history of nonprofits and community organizations that operate in the Greater Hartford region.

Explore!

Read all of our stories about the African American experience Connecticut on our TOPICS page.

GO TO NEXT STORY

GO BACK TO SUMMER 2022 CONTENTS