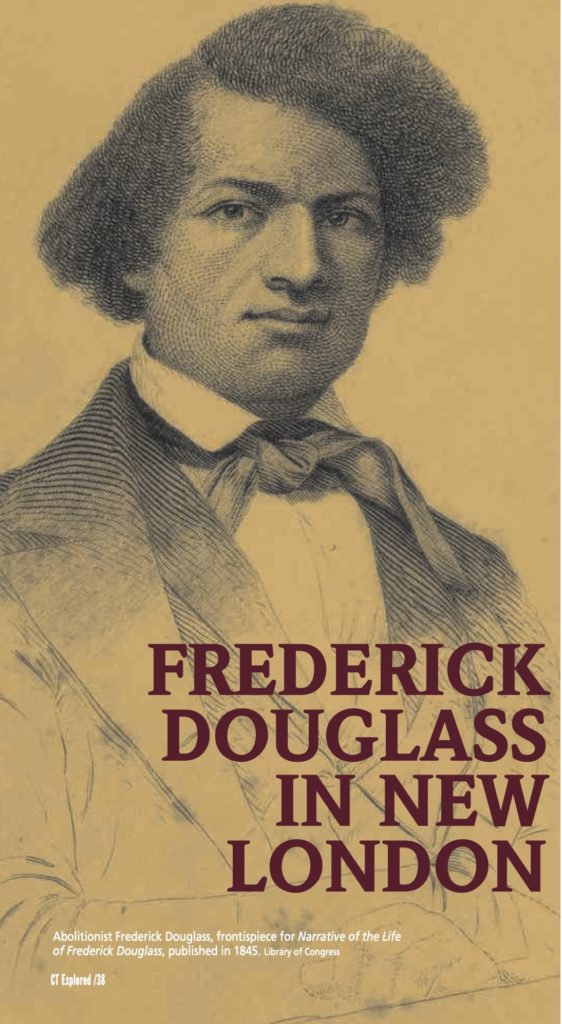

Abolitionist Frederick Douglass, frontispiece for Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, published in 1845. Library of Congress

By Thomas Schuch

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Summer 2022

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

“It is by no means a grateful task to abolitionize Connecticut. As a state, it will probably be the last to be reformed,” wrote Frederick Douglass, the famed orator, Freedom Fighter, and abolitionist, in the May 26, 1848 edition of his newspaper, The North Star. He had just returned home to Rochester, New York from a speaking tour that included four lectures at Dart’s Hall in New London. He continued, “The last two meetings in New London were an exception to this description. The audience manifested a deeper interest in the subject than I had hitherto seen in any part of Connecticut. I think New London about the best part in the state.”

New London’s Whig newspaper, The Daily Chronicle, published an announcement of Douglass’s appearance on Saturday, May 13, 1848, while the city’s Jacksonian Democratic paper, The Daily Star, was silent. No other press accounts of his speech have been found, nor has any record of the attendees.

Douglass described a state divided on the question of abolition, even in this moment when slavery was about to be abolished in Connecticut. New London was divided, too. The city had prospered as a result of its engagement in the lucrative West Indies trade, wherein local farms, fisheries, and forests provisioned sugar plantations of the Caribbean, where millions of kidnapped Africans were enslaved. New London-based ships and crews engaged in the trade often included enslaved human cargo, until it was outlawed in 1774, along with other chattel goods. By 1774 the size of New London’s enslaved population made the city the “greatest slaveholding section of New England,” according to Lorenzo J. Greene’s The Negro in Colonial New England, 1620-1776 (Columbia University Press, 1942). Nearly 10 percent of the population of New London was enslaved at that time, according to census records.

Racism and prejudice against Black people went along with slavery. On April 15, 1717, according to historian Frances Manwaring Caulkins in History of Norwich (H. P. Haven, 1874), New London’s freemen (registered voters) approved a petition to “utterly oppose and protest against Robert Jacklin a Negro man’s buying any land in this town, or being an inhabitant in said town … and recommend that no person of that color should ever have possessions or freehold estate within this government.” Put forward to the general assembly, it did not become law.

New London’s economic connection to slavery would continue in the 19th century as the region became heavily invested in the Southern cotton industry. The city was home to textile mills and to Albertson, Douglas and Company (founded 1846), one of the largest cotton-gin manufacturers in the world, according to Robert Owen Decker in The Whaling City: A History of New London (Globe Pequot, 1976). A broadside (now in the collection of Connecticut Historical Society) invited city residents to a town meeting in September 1835, the purpose of which was to adopt a resolution showing support for “our Southern brethren” and to declare that “this city is decidedly in opposition to the … abolition faction.”

By the 1830s the movements for abolition, Black suffrage, and education, however, were growing stronger across the nation, the state, and in New London. When, in 1837, a controversy arose over educating Black and white children together in New London, Ichabod Pease, an 81-year-old emancipated slave, started a school in his home for Black children, noted an 1846 “Historical Sketch of New London Schools” in the records of the New London County Historical Society. That same year New London white abolitionists Savillion Haley and William Hempsted published The Ultimatum, an anti-slavery newspaper. In 1842 Haley built five houses on Hempstead Street and sold them to free Blacks at cost, creating one of the first Black neighborhoods in the city, according to the National Register of Historic Places.

City residents and sisters Sarah Harris Fayerweather, Celinda Harris Anderson, and Olive Harris Olney were actively engaged in the movements for abolition, education, Black suffrage, and civil rights. Fayerweather, the first Black student at Prudence Crandall’s school, would later become a friend and confidante of Frederick Douglass. Anderson joined with abolitionist Mary Hempstead Bolles as a “Come-Outer,” according to research by Norwich City Historian Dale Plummer, thus becoming part of a widespread movement that publicly condemned local Christian churches that failed to oppose slavery. Olney ran a school for Black children, according to abolitionist Henry Highland Garnet, writing about a visit to the city in The Emancipator (November 19, 1845). Two of the women’s husbands, George Fayerweather and William Anderson, would be delegates to the 1849 Connecticut Colored Men’s Convention.

Three weeks after Douglass spoke in New London, on June 12, 1848, the general assembly abolished slavery in Connecticut, making it the last New England state to do so. Despite Douglass’s expressed concern that it was not “a grateful task to abolitionize Connecticut,” Connecticut may owe Douglass a debt of gratitude for helping bring abolition to fruition.

Tom Schuch is a retired social services executive and New London historian. His research contributed to the development of New London’s Black Heritage Trail.

Explore!

Read all of our stories about the African American experience in Connecticut on our TOPICS page.

New London’s Black Heritage Trail

GO TO NEXT STORY

GO BACK TO SUMMER 2022 CONTENTS