This bucolic scene belies the fact that deforestation characterized Connecticut in the 19th century. “Haymaking in Connecticut,” 1885. Library of Congress

By Walter W. Woodward

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Fall 2018

SUBSCRIBE/BUY THE ISSUE

The Constitution of 1818 is a revolutionary document, not just in what it did but in what it signified—the culmination of a long-fought revolution of the state’s “lesser sort” against the “better sort,” of the “Sitting Ordered” against the venerable “Standing Order.” Even though Connecticut had long and proudly claimed itself to be the most stable self-elected government in America, by 1818 the Land of Steady Habits was on very shaky ground indeed. Almost everything about the state was in transition.

The Constitution of 1818 is a revolutionary document, not just in what it did but in what it signified—the culmination of a long-fought revolution of the state’s “lesser sort” against the “better sort,” of the “Sitting Ordered” against the venerable “Standing Order.” Even though Connecticut had long and proudly claimed itself to be the most stable self-elected government in America, by 1818 the Land of Steady Habits was on very shaky ground indeed. Almost everything about the state was in transition.

The Connecticut landscape the incoming Puritans viewed fearfully as a “savage wilderness,” had been transformed by 1770 into a prosperous colony of farms and villages. But by 1818 Connecticans’ high birth rates (the average family had 6 to 8 children) and the need to provide farmland for succeeding generations had resulted in most of the state’s farmers—by far the bulk of the population—having ever-smaller farms and increasingly tapped-out soils incapable of feeding the families who owned and worked them.

Even climate worked against the Connecticut farmer. The decade from 1810 to 1820 was the worst decade of a climatic period climatologists call The Little Ice Age. This four-century-long (1450-1850) period of global cooling created shorter growing seasons, longer heating seasons, and not infrequent food shortages and crop failures. In southern Connecticut, November snows regularly piled up over second-story windows, while New London harbor was covered in a 15-inch-thick sheet of ice as late as the second week of May. 1816 was the worst year of all, still called the “year without a summer.”

Nature wasn’t the only thing taxing farmers’ prospects in 1818. Connecticut’s system of taxation put a significantly higher burden on farmers than either the state’s merchants or manufacturers, many of whom were members of the ruling elite. A twenty-dollar cow, for example, was taxed the same amount as $200 in stocks was taxed; the owner of a $2,000 farm paid the same amount of taxes as would be paid on $50,000 in cash.

The prospect of depleted land, falling temperatures, and excessive taxation produced a crisis so severe, many Connecticans concluded their only option was to pull up stakes and seek their fortunes elsewhere, in Vermont, New York, or, most likely, that part of northern Ohio called Connecticut’s Western Reserve (See “West of Eden,” Fall 2007). By 1817 young families were leaving the state in droves, producing a crisis of worry for those who stayed. That year, Governor Oliver Wolcott Jr. told the Connecticut General Assembly, “An investigation of the causes which produce the numerous emigrations of our industrious and enterprising young men, is by far the most important subject which can engage our attention.”

Outmigration from Connecticut had in fact been a problem for more than 30 years, and economic difficulties, it turns out, were only one of the factors driving people from the state, as Christopher Bickford et al discuss in Voices of the New Republic: Connecticut Towns, 1800 – 1832 (Connecticut Academy of Arts and Sciences Memoirs, 2003). Two other causes—political oppression and religious intolerance—also played important roles in people’s decisions to leave.

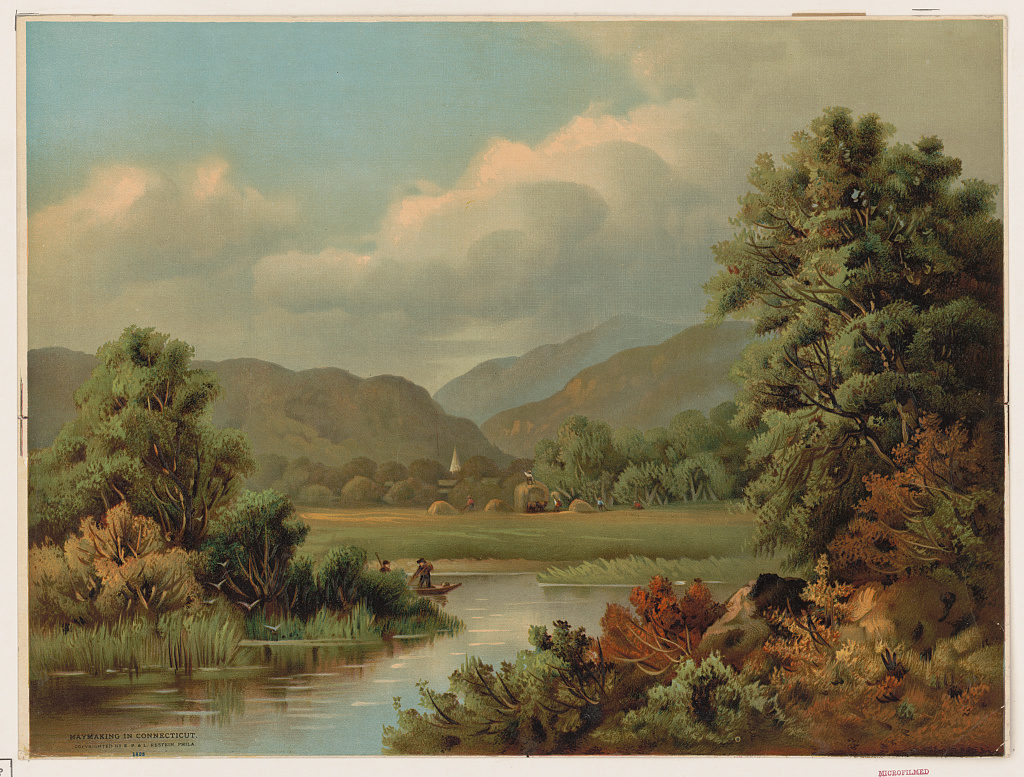

John Haynes, the first governor of the Connecticut Colony, is ensconced on the state capitol. He was an example of the Standing Order: he was governor every other year and deputy governor five times between 1639 and 1654. photo: Carol M. Highsmith, Library of Congress

By 1818 the Land of Steady Habits’s traditional political unity was shattered. The government created by the Fundamental Orders of 1639 was now seen by a majority—though a small one—as fundamentally flawed. That government had been based on the Calvinistic belief that humans were by nature morally depraved and inherently prone to do evil. Wanting to set up a godly commonwealth, Connecticut’s Puritan founders had made the Congregational Church the moral arm of the state. No town could be founded till it had both a church and a minister, whose services people were forced to attend and taxed to support. For his part, the minister was charged with strictly enforcing godly morality and with seeking out and punishing deviants from Puritan norms.He was friend and comforter last, moral judge and jury first and foremost.

In a society whose members were seen as morally depraved, the Puritan founders agreed not just anyone could be chosen to rule. Only the most godly and respectable could or should lead. As a result, Connecticut by 1818 had a centuries-long tradition of government by a preferred, but not quite aristocratic, ruling class, the Standing Order. (See “The Standing Order: Connecticut’s Ruling Aristocracy, 1639 – 1818,” Fall 2012.) Certain families became a hereditary elite, expected to hold and repeatedly be reelected to political office, there to set high standards for themselves and others. This policy was instantiated in the Royal Charter of 1662, which facilitated a self-perpetuating system of preferment in government, the ministry, and, once Yale was established in 1701, the college, too. Not only were leading families the literal leaders, they were also the beneficiaries of the lion’s share of land, largess, and patronage that office-holding provided.

This system of long-term office-holding by known entities had produced in Connecticut—long before the American Revolution—a tradition of stable, well-ordered, and effective self-government of which the members of the Standing Order were justifiably proud. When that fragile political experiment called the United States of America was struggling to create a government equal to establishing stable national authority among confederated but otherwise fiercely competing states, Connecticut proudly held itself up as a model for the new nation to emulate. Noah Webster, in Sketches of American Policy (Hudson and Goodwin, 1785), argued that Connecticut showed how power can be allocated among a central authority, subsidiary jurisdictions, and individual freeman in such a way as to ensure both liberty and order. “Such a government,” he noted, “is of all others the most free and safe. The form is the most perfect on earth.” Widespread confidence in, and respect for, the Connecticut system of government helped Roger Sherman and Oliver Ellsworth persuade delegates to the nation’s 1787 Constitutional Convention to adopt the “Connecticut Compromise” (calling for equal representation in the senate and proportional representation in the house of representatives), which saved that body from gridlock and collapse.

Throughout the storm-tossed years of the early republic—which witnessed crisis after crisis, including Shays’s Rebellion, the Whiskey Rebellion, the XYZ Affair, the Haitian and French Revolutions’ effects in America, and the murder of the former secretary of the treasury by a sitting vice-president—a coterie of Connecticut Standing Order authors—including the then-celebrated group known as the Hartford Wits—issued a steady stream of publications advancing Connecticut’s government as the model for the rest of America to emulate. As Theodore Dwight reminded the country in a speech in New Haven on July 7, 1801, “Connecticut exhibits the only instance in the history of the nations of a government . . . which has stood the test of experience for more than century and a half with firmness enough to withstand the shocks of faction and revolution.” Perhaps the greatest symbol of Connecticut’s vaunted Standing Order stability was physical: the five-year-old Charles Bulfinch-designed State House in Hartford provided a brick and mortar testament-through-design of the stability Connecticut offered and advocated.

Yet even as the Standing Order advanced itself as a model for the nation to emulate, resistance to its tradition of self-perpetuating rule was growing. An array of different interests—each of which felt marginalized by the hereditary powers—sought, ineffectively at first, to change the state’s political steady habit. These included small farmers who felt the Standing Order had for generations rewarded itself with the best land and more of it, merchants and traders who felt excluded from government contracts and political patronage, non-Congregational religious groups such as Baptists, Methodists, Separatists, and (sometimes) Episcopalians who resented the state-established Congregational Church and the series of humiliating, often socially-ostracizing steps they had to go through to gain official permission to worship with their own congregations, immigrants and newcomers who found many doors closed to them, and people with significant investments in the western lands that the Standing Order wanted people to stop going to.

Politically, members of the Standing Order were to a man affiliated with the Federalist Party headed by George Washington and John Adams, so many of the dissidents naturally aligned themselves with the Jeffersonian Republican party headed by the Virginians Thomas Jefferson and James Madison. Since the Federalists controlled every element of Connecticut’s government, they were able, through the first decade of the republic, to exclude the state’s Jeffersonians from all state power with the exception of an inconsequentially few seats in the general assembly. This all changed, however, with the election of Jefferson to the presidency in 1800. Overnight, the state’s political outsiders had access to an array of important federal government patronage positions—in post offices and customs and courthouses, and from these posts they began to make their opposition to the Standing Order’s politics of preferment heard.

Calling for a real constitution—written and ratified by the people and expressing the popular will—the Jeffersonians sought to draw the dissident factions together into a unified and effective opposition party. The Federalists responded with a series of changes to election laws designed to insure the Standing Order would remain standing. The 1801 Stand-up Law eliminated secret ballot nominations for office, forcing those who would nominate Republicans to publicly single themselves out for social and commercial censure. They also put any decisions about disputed elections solely into the hands of Federalist-appointed justices of the peace.

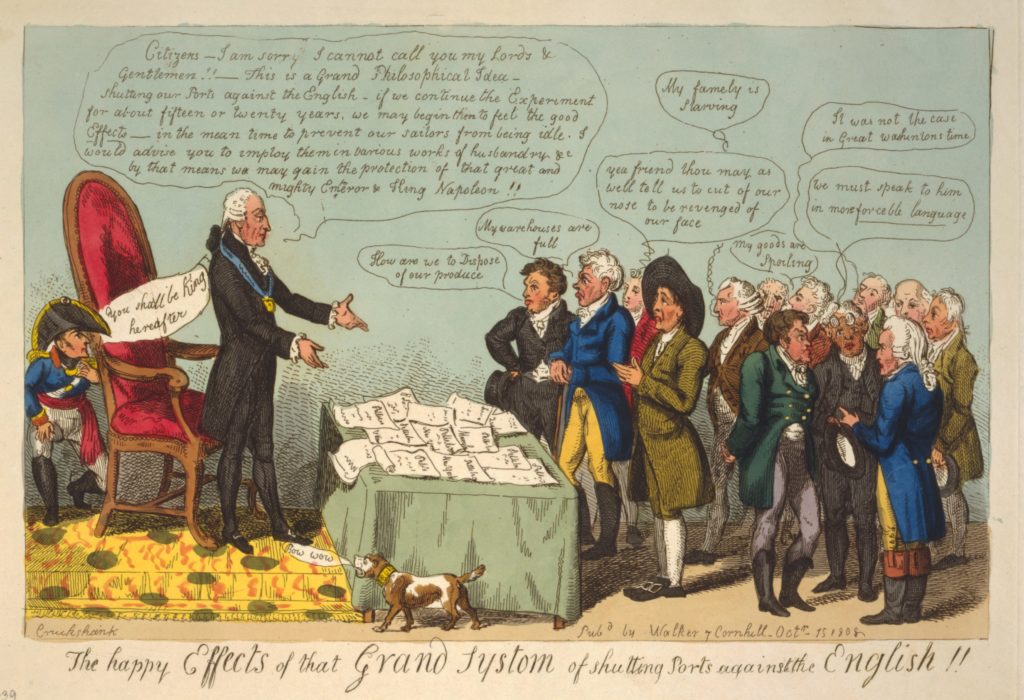

President Jefferson defends his embargo in this political cartoon published in London, October 15, 1808. Library of Congress

Despite these measures, the Jeffersonian opposition achieved substantial minority status. By 1807 Republican representatives made up more than a third of the general assembly’s lower house. However, Jefferson’s Embargo of 1808—a response to British and French insults to American shipping that closed all American ports—devastated the New England economy and Connecticut Republicans’ immediate prospects. Jeffersonian Republican seats in the state house of representatives dropped to 50 in the fall of 1808 and to 42 by 1810. The slide continued into and through the War of 1812—which the Standing Order decried as a Republican-instigated war against New England. By the fall of 1814, even as New England Federalists called for a convention in Hartford to pass measures, possibly including secession from the Union, to force Madison to end the war—the Republican delegate count at the assembly sank to 36.

Throughout this period Connecticut’s Republicans continued to seek alliances with dissident groups, working to craft a unifying political platform capable of overwhelming the deeply entrenched Standing Order. They got their chance after the Federalists’ Hartford Convention backfired. That convention sent delegates to Washington in January 1815 demanding that Madison end the waror else…, only to find the war had already ended, capped by Andrew Jackson’s great victory over the British at New Orleans. Suddenly, the Federalists appeared to the rest of the country—and to many in Connecticut—like traitors. Even former supporters said that the Hartford Convention was now “considered synonymous with treachery and treason,” as the American Watchman Mercury opined on October 25, 1815. The Federalist Party was destroyed. (See “The ‘Notorious’ Hartford Convention,” Summer 2012.)

Capitalizing on the Federalists’ disgrace, a Republican-led coalition met in New Haven in February 1816 to form a new political party. Calling itself the American Toleration and Reform Ticket—quickly known as the Toleration Party—it put forth candidates and positions designed to unite the state’s disgruntled minorities. Oliver Wolcott Jr., the Republican son of a former Standing Order governor and member of one of Connecticut’s hereditary ruling families, was the new party’s choice for governor. (See “The People’s Governor,” Fall 2018) The Toleration Party called for a new constitution, ecclesiastical reform that would allow every man to worship according to his own conscience without interference, equal advantages in colleges and schools, expanded white male suffrage, and more transparency in the legislature. Calling on rich and poor, townsmen and countrymen to pull together,the party brought together disparate groups in a coalition to break the stranglehold the Standing Order had had on Connecticut government for more than 175 years. It took three years, but in the end the party succeeded.

In 1816 the Tolerationists gained a majority in the general assembly’s lower house. In 1817, with Wolcott Jr. as candidate, they added the governorship. Finally, in 1818, the Toleration Party carried the lower house, the council, and the governorship, paving the way for the state constitutional convention held that summer. At last, they had the coalition and the control needed to change the laws and dismantle or amend the structure of government that had undergirded Standing Order entitlement for 179 years. They lost little time in doing so.

Connecticut’s Old State House where both the Hartford Convention and the state constitution convention too place. Connecticut’s Old State House

In early June, as Douglas Arnold summarizes in the introduction to The Public Records of the State of Connecticut (Vol. XIX), following a recommendation from Governor Wolcott, the reform majority in the lower house voted to call a constitutional convention and to hold it at the state house in Hartford, in order, as one member said, to “wipe off the disgrace” of the Hartford convention, held there four years earlier. They called for the electors in every town to assemble at their voting places at 9 a.m. on July 4 to elect delegates to the convention, equal to the number of representatives each town sent to the state’s lower house. When the votes were counted, reform-oriented coalition delegates outnumbered defenders of the Standing Order by from 9 to as many as 30 votes (depending on the issue under consideration).

The convention assembled on August 26, electing Governor Wolcott president of the constitutional convention and appointing a 24-member committee to draft the constitution in which reformers held a 19-to-5 majority. That committee presented a proposed constitution—much of it originally drafted by Governor Wolcott—within a week, and from September 1 to 15 delegates considered and debated each proposed article, accepting or amending its provisions.

On September 15 the convention voted 134 to 61 to submit the constitution as revised to a public referendum. In a crucial move, they required only a simple majority for passage. Three weeks later, on October 5, the constitution was ratified by a popular vote of 13,918 (53 percent) for to 12,364 (47 percent) against (26,282 votes cast out of Connecticut’s total population of about 270,000). By a close margin, the revolution of the “lesser sort” against the “better sort,” of the “sitting ordered” against the “Standing Order,” was complete.

What exactly did the Constitution of 1818 do? The list is significant:

- It replaced the 1662 royal charter with a written constitution, ratified by the people.

- It included a declaration of 21 fundamental individual rights the state could not usurp.

- It effectively implemented universal white male suffrage—allowing all white freemen, and men over 21 who served in the militia or paid taxes, to vote. (To its discredit, the constitutional convention explicitly rejected proposals that African American men, and women, too, be given the vote.)

- It reorganized the government into three distinct branches—executive, legislative, and judicial—with separation of powers as the basic organizing principle. This involved creating a separate (and open) senate and executive department, giving the governor power to propose and veto legislation, and creating an independent judiciary whose high court members were no longer dependent on legislative approval to retain office.

- It disestablished the Congregational Church as the official state church, and confirmed the principle of freedom of conscience for all Christians.

Historians in both the 19th and 20th centuries, reviewing the impact of the Constitution of 1818, have often considered it a relatively conservative and benign document whose greatest impact was either the division of the government into three separate branches (Swift, Whitman, and Day, Revised Statutes, 1821) or the separation of church and state (Purcell, Connecticut in Transition, 1963). What they often forget is that this seemingly conservative document signaled the victory of a previously marginalized coalition of second-class Connecticans against a self-selected group of hereditary office-holders who had clenched the reins of power to themselves for 179 years.

Walter Woodward is the Connecticut state historian.

READ MORE!

Find links to related stories from past issues and podcasts about the Constitution of 1818 HERE.