by Lary Bloom

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. SUMMER 2007

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

Among the tender memories of youth: My father atop a ladder, examining the remote winesaps of a tall tree, choosing only the flawless specimens to toss to me to deposit in the bushel basket.

This annual pick-our-own apple harvest occurred in the picture-perfect village of Hudson, Ohio, many miles from our modest home in a working-class suburb.

The community that became our regular autumn destination was named for its founder, David Hudson, a native of Goshen, Connecticut. During the years of our outings, I had never heard of David Hudson and knew nothing of Connecticut’s intense connection with the state in which I was born. What I certainly knew was that Hudson, Ohio, was startling in its beauty. Its formal town green featured leafy oaks and a white-steepled church. All around it were stately houses in the colonial style.

“Why can’t we live here?” I asked my father. He shrugged, but I knew the answer. We were not wealthy enough, and not Congregationalist enough.

Many decades later, when I migrated eastward and settled in Connecticut, I was often reminded of Hudson while driving through the state. And I felt that in settling here I was, in a broad sense, coming home. For I am a native of what once was known as the New Connecticut, or, as it is most often referred to by historians, the Connecticut Western Reserve.

Author William Donahue Ellis, in his 1966 book The Cuyahoga, also pointed out the similarities, but from the local native’s point of view. “Connecticut people traveling northern Ohio are always startled to find themselves home. The towns and streets have Connecticut names. The houses have Connecticut architecture. The towns have Connecticut-type governments. The phone books are filled with grand old Connecticut names.”

Even so, many well-read and astute local folks remain unaware of our collective Ohio connection, and so I point it out whenever I can. It’s true that I may be pressing the point too far when I argue that it is not the Boston Red Sox or New York Yankees who qualify as Connecticut’s home team but the Cleveland Indians. Whether you buy this notion or not, there is no doubt that the general lesson of the Western Reserve remains valuable—particularly now, when it has a new relevance.

Connecticut Governor M. Jodi Rell announced early this year a proposal to raise the income tax rate in order to increase funding for the state’s public schools. But if she were to let history be her guide, she might also consider a different way to boost revenues: land speculation.

For when I was growing up in the Western Reserve, among the things I didn’t understand was that the part of the country where I lived was even then helping to educate the children of Connecticut. It has done so for two centuries, and it continues to do so today.

Here’s a hint as to why: In the region of my youth were townships called Suffield, Avon, Coventry, Litchfield, Orange, Vernon, Hartford, Chester, and Madison. Not merely by coincidence—but as the result of commerce, ambition, educational vision, and, well, greed.

Way to the West

There was a time when Connecticut considered itself too big for its breeches. Far too big, and in this it resembled other states (such as Virginia and New York) that made major claims on lands to the west.

In April 1662, King Charles II signed a charter that indicated the borders of Connecticut stretched from the Narragansett Bay all the way to the “great sea south”—a reference to what became known as the Pacific Ocean. The northern boundary was to be the Massachusetts Bay colony line. The swath of land eventually came to be bounded approximately by the 41st and 42nd parallels. This meant, according to the charter, that Connecticut owned a strip of land 67 miles deep and 3,000 miles wide—a pretty decent asparagus patch, and perhaps more than King Charles II had really had in mind. The charter was pretentious, of course, and untenable. The practical outcome was that the state eventually claimed ownership of land once occupied by Native American tribes, a result of a settlement following a war that featured the exploits of General “Mad Anthony” Wayne.

The land that Connecticut ended up with was about 3,500,000 acres of fertile property, land that looked familiar but whose soil, to the delight of those who eventually tilled it, was largely free of the rocks known as New England potatoes.

As devised in 1795, the legislature’s plan was to sell this land and use the proceeds to create a “perpetual school fund.” The principal from the sales would be protected, and any interest from mortgages or bonds would be distributed annually to school districts according to the number of students each had.

This is not to say that there was universal agreement to establish such a fund. Some Connecticut citizens held the view that the lands to the west should be held and developed for future expansion of the state. One critic, whose identity is not known today, argued that the educational system as it stood was “good enough, if not too good.” Nevertheless, the act was passed.

A portion of the territory set aside became known as the Firelands. This 500,000 acres was reserved by Connecticut for victims of the fires set by the British in New London, Groton, Danbury, and other communities during the Revolutionary War. The rest was up for grabs. But it took some time to achieve a selling price suitable to the legislature. Early bids hovered around $1,000,000 and were deemed unacceptable. Eventually a bid for $1,200,000, or about 36 cents an acre, was submitted by Oliver Phelps of Suffield (the Phelps of Connecticut Landmarks’s Phelps Hatheway House in Suffield) and associates.

This was a group of 35 Connecticut men (representing, in all, 57) who banded together eventually under the banner of the Connecticut Land Company to buy all available territory in the Western Reserve. Most of the investors took out heavy mortgages on their property or used bonds; the state required mortgages and bonds be signed by each buyer as a condition of sale. The sale was consummated at the Old State House on September 2, 1795.

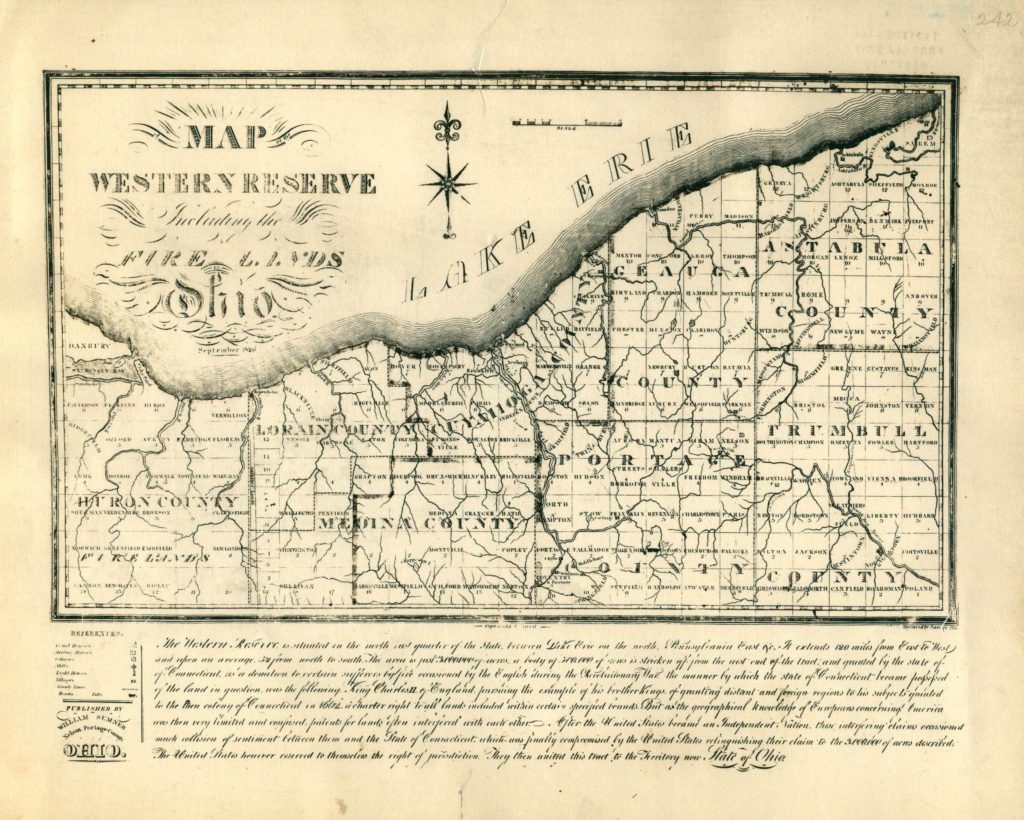

Charting New Territory

The president of the Connecticut Land Company was one Moses Cleaveland, of Canterbury, who became superintendent of the exploration and surveying party. The group traveled west for 68 days. Once in what later became known as Ohio, Cleaveland went to work to clear up claims for the land with local tribes and to stake out reasonable property lines.

Cleaveland, however, faced pressure from all sides. Investors back home were impatient. And this work in the Western Reserve was not without severe hardship. The advance party suffered from ague, hunger, and dysentery. Many of the men complained that the pay, three dollars a week, was too low. The food wasn’t ideal, either—muskrat, rattlesnake, bear, and, whenever possible, rabbit. There was nearly a full-fledged revolt as Cleaveland tried to survey the land on the banks of the Cuyahoga intended to be the headquarters city. The workers threatened to head back to Connecticut. Cleaveland had no more money to give them, but he did have land. He pointed to the map and gave an inspiring speech about the “hordes” of immigrants who one day would stream there and create a great market for such property. He boldly predicted that the community he founded on the banks of the Cuyahoga River, a city that would be named after him (though with an altered spelling for reasons not entirely clear) “will grow to nearly the size of Old Windham, Connecticut.” And, to take the spark out of the rebellion, he offered each worker a share of the land.

In time, Cleaveland’s predictions proved prescient. Many settlers made the journey west and built homes and communities that felt familiar to them. Others arrived from far-flung locations. (Indeed, Cleveland turned into an industrial boomtown and by the early 20 th century was the sixth most populous city in the United States, though it has fallen far back in the ranking in recent decades.)

The early settlers faced difficult conditions as they tried to set up households very much like the ones they once knew back in Connecticut.

A portion of a letter written by Eunice (Spencer) Hanchet of Mantua, Portage County, Ohio, to her sister-in-law, Elizabeth (King) Spencer back in Suffield, Connecticut on October 9, 1802:

…Our house is about as good as our neighbours yet it is so small as to be very convenient for I don’t now have to run from one large room to another to do my work but here I have it all at hand. Our house according to the custom of this country is composed of logs. One end of it is chiefly taken up with the chimney, oven, sink and a few pegs to hang up my rolling pin, towels, cheese hoop, tea kettle, and frying pan. At the other is a small bedroom adorned with rows of pegs to hang our clothes upon…On the front side of the door [and]a small window and space for the pot and kettles and a peg to hang up my broom. On the back side are those shelves on which I have my crockery, pewter, tins, and glasses. Under my looking glass are several pegs on which I hang my…shears, snuffer, work bag…and over our other small window is the book shelf which together with a few more useful pegs fill up the remaining part of the space. The chamber is filled up with a bed, bins, wheat and corn, barrels of flower and all such trumpery as we wish to put out of sight.…

While the women of the new territory found ways to adjust, many of the men were having trouble paying their debts. As historian William Donahue Ellis put it, Connecticut’s “playing God that way, even over only 3,000,000 acres, brought disaster, bankruptcy, complete stagnation, and poverty.”

Revenue, as a result, was only trickling in. In 1809, interest due on the balance of the loans had reached half of the principal. The whole enterprise seemed in jeopardy, until the heroic and innovative tenure of a man almost lost to history but whose innovations could apply today.

On Distant Soil, Cultivating Education

James Hillhouse, an imposing figure in his powdered wig and knee buckles, became commissioner of the education fund. His achievements over the years, beginning in 1810, were astounding. According to Ellis, “James Hillhouse, perhaps more than anyone, created the Western Reserve.”

As a young captain in the Revolutionary War, Hillhouse had marched out of New Haven with 30 young men to meet the British invasion of 1779. He was a Yale grad, a lawyer, and good at economics. He had been elected to the U.S. Senate and served from 1797 to the time when he resigned to take his new job as, in effect, the bill collector in the Western Reserve.

In this work, he never threatened to send debtors to jail. Instead, he immersed himself in the fortunes and misfortunes of the debtors. What he found, according to Ellis, “was a hopeless roster of poverty and bankruptcy caused by the Land Company, sometimes wiping out two generations of the same family where stock in the Land Company had been passed on by inheritance, along with its backbreaking obligations.”

Instead of punishing these people, he invested in each of them. His job, he decided, was to make these needy people prosperous, and so he counseled each on the art of making money from the land. He identified what assets they should keep, what they should sell, and how otherwise they might become entrepreneurial. This began to turn the whole project around.

Even so, the state of Connecticut now found itself in a land business it didn’t want. Instead of cash payments for debts, the state was receiving property in places like upstate New York. And yet, slowly but steadily, dividends were soon becoming available on a regular basis, and Connecticut’s schools began to benefit.

Historian Thomas Howard, who did much research for this article, points out the considerable connections between certain Connecticut towns and the Western Reserve. Suffield buyers, for instance, contributed about 28 percent of the original $1,200,000 purchase price. There were similar figures throughout the 19 th century in other towns. In turn, Suffield’s public schools benefited from interest payments over the years. Howard found that in 1885, for instance, the town reaped $1,642.20 from the fund, a sum representing 29 percent of its annual education budget at the time.

And for the year 2005, the latest year for which figures are available, records in the state treasurer’s office show the fund was worth $9,197,637.

All this, however, remains largely unknown to a public that, quite understandably, worries about how to pay for schools. (As impressive as several million dollars may sound, it’s a drop in the bucket compared to the combined budgets of our state’s schools. The proposed budget for next year in the town of Westport alone is nearly $90 million.)

The legacy of our pioneers and their vision for education makes a great lesson for us. And so it is unfortunate that people like James Hillhouse and Moses Cleaveland—and many others who were instrumental in this movement—have never received the credit they deserve.

I have made my own pilgrimage to Canterbury, Connecticut on a few occasions, to pay respects to a hero (Moses Cleaveland) and a heroine (Prudence Crandall, embattled teacher of “little misses of color”).

On one of those occasions I drove to an old town cemetery off the main highway, where many of the Cleavelands were buried over the years. Near the front of the cemetery is a monument, almost the height of a winesap tree. It is in memory of the man who led the expedition from Connecticut to Ohio in 1795.

But the monument was not erected by anyone in Connecticut. It was paid for, built, and dedicated in 1906, by the “grateful citizens” of Cleveland, Ohio.

Lary Bloom writes columns for The New York Times and Connecticut magazine. His newest book, “Letters From Nuremberg,” co-authored with Senator Christopher J. Dodd, will be published in September by Crown. He lives in Chester.

Special thanks to Thomas Howard, an East Granby historian and researcher, for his assistance with this article.