The “Notorious” Hartford Convention

The “Notorious” Hartford Convention

By Matthew Warshauer

(c) Connecticut Explored Summer 2012

Subscribe!/Buy the Issue

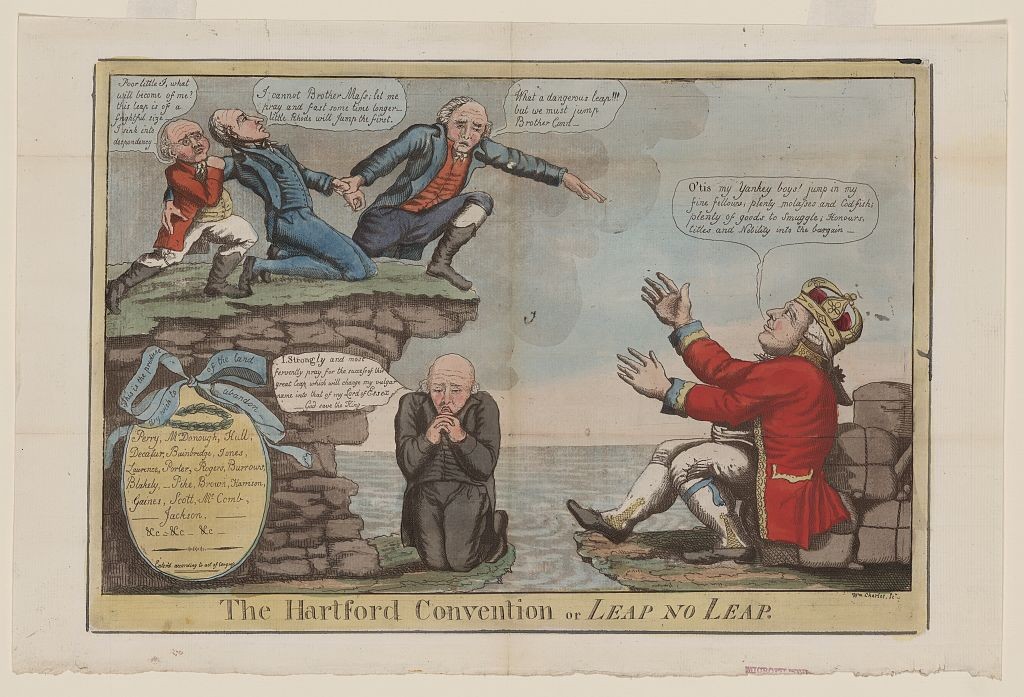

From December 15, 1814 through January 5, 1815, 26 delegates from Massachusetts, Connecticut, Rhode Island, and representatives from counties in New Hampshire and Vermont, met at the State House in Hartford to discuss the many egregious problems the region faced as a result of the ongoing War of 1812. Dubbed the Hartford Convention, the gathering was viewed with suspicion from the outset. Some theorized that the Convention’s primary aims were to promote secession from the Union and to forge for the New England states a separate peace and trade alliance with Great Britain. President James Madison was so concerned that he sent Major Thomas S. Jesup to keep a watchful eye on the proceedings. Years later as reported in the National Intelligencer (May 7, 1824), and while running for president, Andrew Jackson famously announced, “Had I commanded the military Department where the Hartford convention met, If it had been the last act of my life, I should have hung up the three principle [sic]leaders.”

Such views and the seemingly “radical” resolutions and constitutional amendments advocated by the delegates have forever tainted the Hartford Convention as a self-serving, traitorous affair. With the actual secession of southern states during the American Civil War still years away, the actions of Federalist New England, it’s commonly held, marked the first time disunion had threatened the nation. The reality is somewhat different, and we cannot begin to understand New England’s rationale for holding the Convention or its ultimate outcome without first considering the remarkable political tensions that arose at the time of the nation’s founding and extended well through the War of 1812.

The Hartford Convention represented a last-ditch effort on the part of New England Federalists to reclaim the region’s former eminence. As part of the original 13 colonies, and with Boston at the heart of the American Revolution, New England had enjoyed considerable influence over the developing nation. That sway, however, was weakened almost immediately as the southern and western states continued to multiply in number, expanding the ranks of the emerging Republican Party. Federalists were largely cooped up in New England, with additional party devotees scattered throughout parts of New York and the mid-Atlantic states. The Louisiana Purchase further exacerbated this situation and was in many ways a death knell to the Federalists; it roughly doubled the size of the nation, furthered westward expansion, and promised a continued diminution of New England’s political influence.

The divide between New England and its neighbors to the south was immediate in the aftermath of the nation’s founding under the Constitution. George Washington had agreed to become the first president in the hopes of bringing solidarity to the new nation, establishing for it a strong foundation. What he experienced distressed him beyond measure and revealed his deepest foreboding for the future. His cabinet was divided between Federalists, who coalesced around Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton, and Republicans, who followed Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson. The two men disagreed on everything, but both viewed economics and foreign policy as tightly interwoven issues that spoke to his vision of America. Hamilton dreamed of a manufacturing giant modeled in the image of England and linked to her vast trade empire. Jefferson viewed such ideas as anathema: To him, they betrayed the Revolution’s meaning and left the nation to be treated as little more than a colony. Jefferson argued instead for an agricultural future, one that secured independence and saddled America with no onerous British alliances.

The divide between New England and its neighbors to the south was immediate in the aftermath of the nation’s founding under the Constitution. George Washington had agreed to become the first president in the hopes of bringing solidarity to the new nation, establishing for it a strong foundation. What he experienced distressed him beyond measure and revealed his deepest foreboding for the future. His cabinet was divided between Federalists, who coalesced around Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton, and Republicans, who followed Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson. The two men disagreed on everything, but both viewed economics and foreign policy as tightly interwoven issues that spoke to his vision of America. Hamilton dreamed of a manufacturing giant modeled in the image of England and linked to her vast trade empire. Jefferson viewed such ideas as anathema: To him, they betrayed the Revolution’s meaning and left the nation to be treated as little more than a colony. Jefferson argued instead for an agricultural future, one that secured independence and saddled America with no onerous British alliances.

The dispute between the two men caused Jefferson to resign his cabinet post. Vicious partisan attacks appeared in Republican newspapers, even on the previously untouchable Washington, escalated, and the president agreed to a second term only under the severest pressure and sense of duty to the nation. His inaugural address—at only two paragraphs, the shortest in American history—challenged enemies to prove he had “violated willingly or knowingly” his oath of office. When he finally retired, in 1797, Washington issued a “Farewell Address” in which he warned his countrymen that sectional divisions posed the greatest danger to the new nation.

Republican power continued to grow, and the party took control of the government, first with the election of Jefferson (1800-1808) and then with that of James Madison (1808-1816). Federalist New England worried about its lost influence, the Republican Party’s unreasonable (in the Federalists’ view) anti-British sentiment, and the economic toll of the Napoleonic wars. These issues spoke directly to the clear divide between Federalist and Republicans. When America ultimately declared war on Great Britain on June 18, 1812, Federalists railed against what they viewed as a misguided, disastrous foreign and economic policy.

Historians agree that most Americans today know little of the war, even to the extent that few can name the principal combatants–the United States and Great Britain. Often touted as the “Second War of Independence,” the nation’s repeat conflict with her former mother entailed just as much internal dispute and contention as did the first. The loudest and most virulent opposition occurred in the Northeast and easily made its way to Washington. There, Federalist senators and representatives did everything in their power to thwart the country’s military efforts, voting as a bloc in Congress more than 90 percent of the time. First they opposed to the war’s declaration, and then voted against measures regarding raising men and money and restricting trade with the enemy. New England governors refused to allow their militia troops to invade Canada as part of the military campaign, insisting that they were solely a defensive force, and Federalists in Hartford went so far as to pass ordinances restricting parades and the playing of martial music in order to dampen any spirit for recruitment.

President Madison’s strategy hinged on engaging England while that country was bogged down in the decades-long Napoleonic struggle in Europe. This lessened the likelihood of a significant British troop movement in America or of England’s sending troops to reinforce Canada’s military. The U.S. approach was a disaster. First, American forces in Canada were repulsed at every turn, even without England’s having much military presence there. Second was England’s unleashing thousands of seasoned, veteran troops on America when the Napoleonic wars ended in 1814. British troops invaded Washington in August, setting virtually every public building on fire. It was a distinct low point in the war and was viewed by many as merely a hint of what English troops might do next.

As British naval depredations on the New England coast continued, Federalist governors complained bitterly that their states’ defense needs were not being met by the Madison administration.[i] It was in this atmosphere of long-standing partisanship, the failures and misery of the war and the heavily strained bonds of national unity, that the seeds of the Hartford Convention sprouted. In October, leading New England Federalists began advocating a regional meeting to air their many grievances. When they agreed to gather in Hartford at the beginning of December, word immediately got out. In early November the Connecticut Courant published a series of articles headlined, “What is expected of the Convention at Hartford. What it can do and what it ought to do.” Vigorously Federalist, the Courant voiced what many in New England believed: “Our sovereignty is invaded. Our rights are trampled under foot. The Union which is an union of sovereignties has been violated by deserting some of them, while others have been unnecessarily defended, by drawing all the resources from some states which were endangered to defend others which were not. This is not one hundredth part of our wrongs and breaches of the Union.”

Such strident denunciations, combined with the very idea that New England states were gathering, caused many to suspect the end of the fragile U.S. alliance. Yet Federalists insisted early on, and in the Convention’s aftermath, that secession—withdrawal from the Union—was not its aim. The Connecticut General Assembly appointed its delegates with the express instruction “to do nothing inconsistent with the states obligation to the union.”[ii] Calvin Goddard, a member of the General Assembly and delegate from Connecticut, wrote emphatically to Connecticut Senator David Daggett, November 1, 1814, “I am no rebel—have no scheme of severing the union. I should consider it an evil of no small magnitude if accomplished by a compact in the most peaceable way.” Still, unsettling concerns remained.

Over three weeks in the depth of winter, delegates met behind closed doors in Hartford to amass their complaints and determine New England’s course of action. The secrecy merely added to the rumors and sense of foreboding. Would the nation face the prospects of a divided Union while at the same time awaiting the next British assault? The answer came in the form of the official “Report and Resolutions of the Hartford Convention,” which announced four resolutions and recommended seven amendments to the U.S. Constitution. None of the proposals mentioned such radical notions as secession, focusing instead on the common complaint that the U.S. had not properly defended New England or allowed the region to defend itself. Indeed, the first three resolutions focused on the “protection of citizens,” “the defense of their [the state’s]territory against the enemy, and a reasonable portion of the taxes” to accomplish that end, and allowing states to retain a detachment of militia significant enough “to repel any invasion.”

In many ways, the proposed constitutional amendments revealed the far more serious and long-term problem faced by Federalist New England: its waning power since the nation’s inception. Most of the amendments dealt specifically with this issue. The first item addressed by the Convention was elimination of the famous “3/5 clause,” which awarded southern states additional representatives in the House based on the size of their slave populations. This bonus, so illustrative of the South’s rising power, had irked northerners for years. The Convention further pressed to change congressional voting rules to favor the New England minority and insisting that no new states should be admitted and no declaration of war passed without a two-thirds (rather than a simple) majority vote; other proposals included limiting the presidency to one term and allowing no person from the same state as the sitting president to be elected in his succession. These, and other demands, represented the Federalists’ attempt to reclaim their diminishing power.

The Report’s final resolution drew criticism for revealing the Convention’s secessionist designs. Federalists threatened that if their proposals were not addressed and, as the Report asserted, “peace should not be concluded, and the defence of these states should be neglected, as it has been since the commencement of the war, it will, in the opinion of this convention, be expedient for the legislatures of the several states to appoint delegates to another convention, to meet at Boston . . . with such powers and instructions as the exigency of a crisis so momentous may require.”

Timing for the Convention and its Report was everything. Federalists met at a time when the nation was at its lowest point, following the capital’s invasion and with the potential for the war to continue in the same disastrous direction. If indeed that had happened, the Federalists may have stood on firm ground. Instead, the earth shifted beneath their feet with the unexpected announcement of the Treaty of Ghent (signed on December 24, 1814), followed by General Andrew Jackson’s stunning victory at New Orleans (January 8, 1815). In a battle that most expected to be lost, Jackson demolished a seasoned British army and in doing so achieved both the greatest American military victory up to that time and lifted the nation’s war gloom. The combined events completely undid the Federalist power gambit. Republicans were able to spin the end of the war into a grand success for the nation and, in the warmth of a patriotic glow, cast Federalists as the ultimate traitors to the American cause. The Federalists’ stalwart opposition to every aspect of the war, followed by the “traitorous” Convention, made that an easy task.

The Federalist Party had been declining for years, and the Hartford Convention proved the final nail in the party’s coffin. To this day modern American political parties heed the sage historical lesson that one can oppose a war, but not the raising or funding of troops. The Hartford Convention has been forever tainted by its hint at secession, though that certainly was not the initial Federalist goal. Rather, party members hoped to address their continuing loss of power in the early years of the new republic and to voice their stern opposition to the war and the beleaguered position in which it had left the region in terms of military defense. They succeeded in neither of these goals.

Matthew Warshauer is professor of history at Central Connecticut State University and chair of Connecticut Explored’s editorial board. He is author of Connecticut in the American Civil War: Slavery, Sacrifice, and Survival (Wesleyan University Press, 2011).

[i] Donald R. Hickey,. “New England’s Defense Problem and the Genesis of the Hartford Convention,” New England Quarterly 50, No. 4 (1977); Samuel E. Morison, Harrison Gary Otis 1765-1848: The Urbane Federalist (Houghton Mifflin Company, 1969)

[ii] Glenn Tucker, Poltroons and Patriots (Bobbs Merrill, 1954),

Explore!

Read all of our stories about Connecticut in the War of 1812 in our Summer 2012 issue

Read all of our stories about the Constitution of 1818 on our TOPICS page