By Elizabeth Pratt Fox

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Summer 2017

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

From sipping Madeira from fine, imported glasses in the 17th century to imbibing the signature cocktails of today, the consumption of alcoholic drinks has been a part of the culture of the state and the country, even during the national prohibition era from1920 to 1933.

From sipping Madeira from fine, imported glasses in the 17th century to imbibing the signature cocktails of today, the consumption of alcoholic drinks has been a part of the culture of the state and the country, even during the national prohibition era from1920 to 1933.

But the melding of modern design and the surging popularity of the cocktail in the 1930s and 1940s, combined with the creativity of Connecticut’s metal manufacturers looking for new markets in the Great Depression, resulted in production of shakers that are as valued today as they were when they were made.

In the 1930s the cocktail party gained popularity and acceptance through its depiction on the silver screen. Shakers were part of the action in such movies as The Thin Man (1934), Manhattan Melodrama (1934), and After Office Hours (1935). Cocktail dresses and cocktail napkins became part of the post-prohibition vocabulary, too. Connecticut produced not only the vodka and shakers for drinks such as the martini but also many of the swizzle sticks, muddlers, jiggers, strainers, and cups that mixed and held the cocktails, along with wine coolers, ice buckets, and tongs.

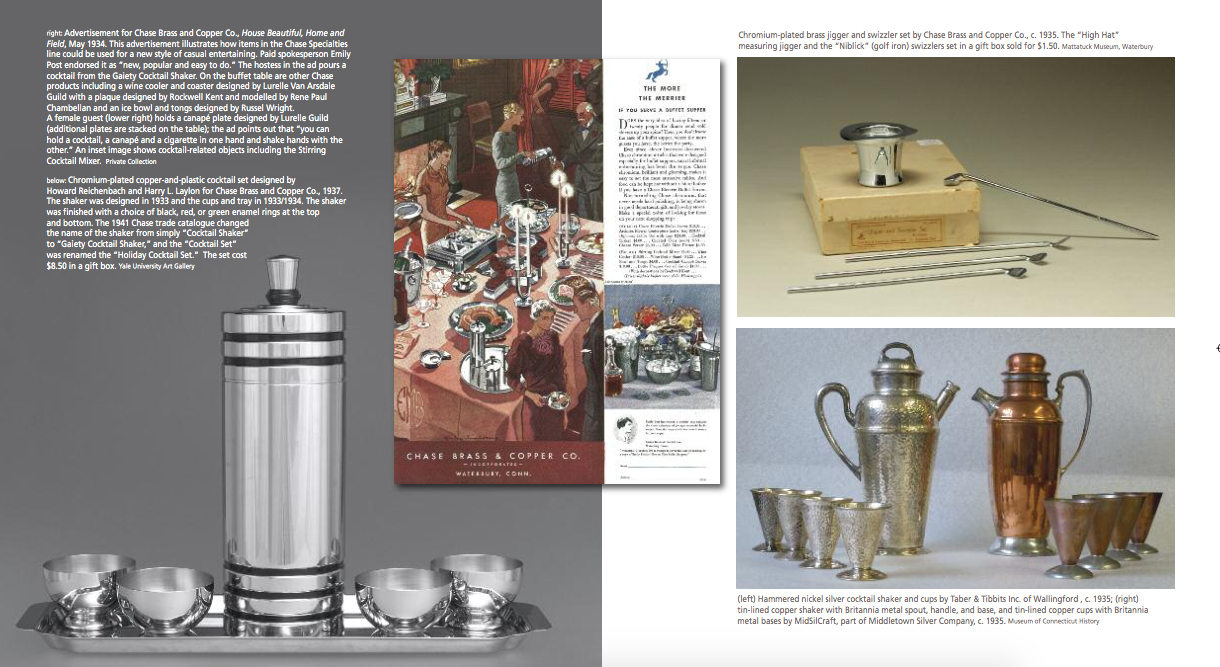

One of the largest producers of shakers and related accessories was the Chase Brass and Copper Company of Waterbury, which manufactured chromium-plated entertainment wares from 1930 until 1942. The company moved into this line during the Great Depression looking for new markets and then transitioned to war production in 1941, never returning to this market after the war. As Dave Corrigan explained in “The Depression Gave us—the Buffet Server?” (Connecticut Explored, Winter 2010/11) the company’s marketing genius made owning a shaker and Chase Brass’s other items for casual entertaining seem like a requirement for anyone wishing to be modern and stylish.

Chase Brass hired well known industrial designers and artists such as Walter Van Nessen, Russel Wright, Lurelle Guild, Howard Reichenbach, and Rockwell Kent, some of whose work is illustrated here, to design sophisticated wares for the table. Their designs were given provocative names such as “The Moderne,” “The Aristocrat,” the “Gaiety,” and the “Blue Moon.” With promotion by Chase, International Silver, and other Connecticut companies, the cocktail party and the buffet dinner that often accompanied it became a fixture in the well-to-do Depression- and World War II-era American home.

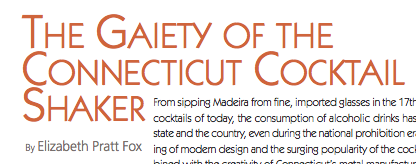

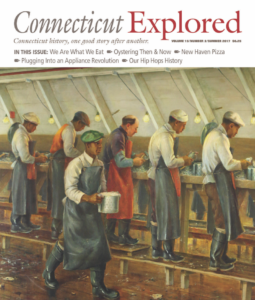

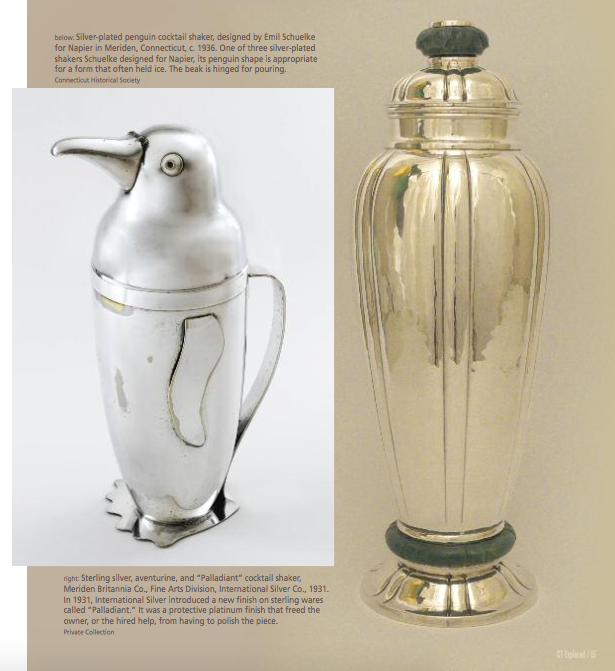

Chase Brass hired well known industrial designers and artists such as Walter Van Nessen, Russel Wright, Lurelle Guild, Howard Reichenbach, and Rockwell Kent, some of whose work is illustrated here, to design sophisticated wares for the table. Their designs were given provocative names such as “The Moderne,” “The Aristocrat,” the “Gaiety,” and the “Blue Moon.” With promotion by Chase, International Silver, and other Connecticut companies, the cocktail party and the buffet dinner that often accompanied it became a fixture in the well-to-do Depression- and World War II-era American home. Manufactured in sterling silver, silver-plate, nickel silver, chromium-plated brass, and copper, shakers almost always had an interior strainer, rather than relying on a separate strainer. Manning-Bowman of Meriden, however, also made hand-held strainers. The shakers came in many different shapes, from cylindrical to tapered sides, with or without handles and spouts. They also came in whimsical shapes such as penguins and lighthouses (see International Silver’s spectacular lighthouse-shaped shaker in “International Silver Shines Once More,” Winter 2015/16).

Manufactured in sterling silver, silver-plate, nickel silver, chromium-plated brass, and copper, shakers almost always had an interior strainer, rather than relying on a separate strainer. Manning-Bowman of Meriden, however, also made hand-held strainers. The shakers came in many different shapes, from cylindrical to tapered sides, with or without handles and spouts. They also came in whimsical shapes such as penguins and lighthouses (see International Silver’s spectacular lighthouse-shaped shaker in “International Silver Shines Once More,” Winter 2015/16).

Elizabeth Pratt Fox is a museum and historic site consultant. She most recently wrote “Woodbury: Zimri Moody, Cabinetmaker,” in the Summer 2016 issue.