(c) Connecticut Explored Inc, Fall 2018

SUBCRIBE/BUY THE ISSUE!

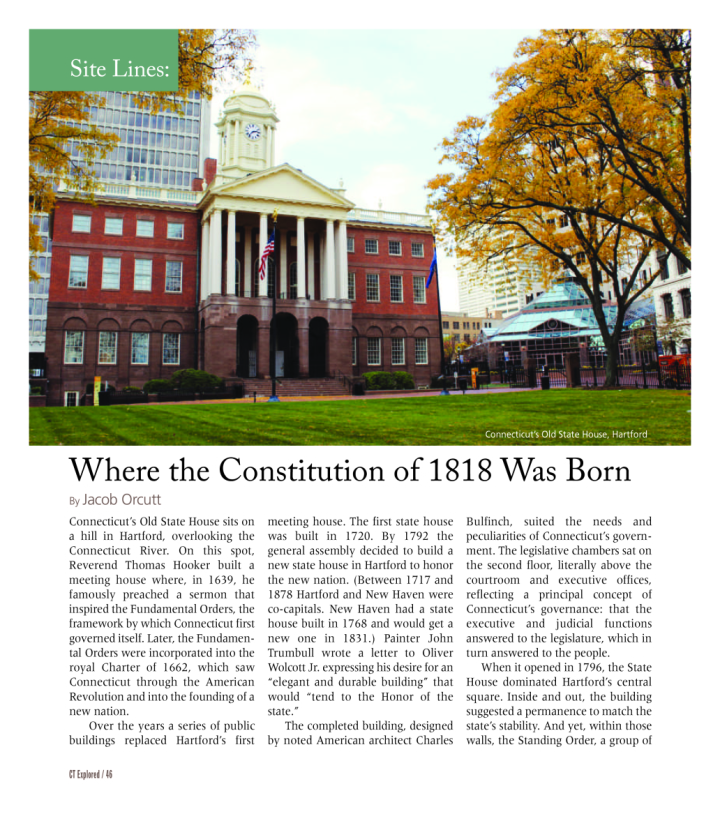

Connecticut’s Old State House sits on a hill in Hartford, overlooking the Connecticut River. On this spot, Reverend Thomas Hooker built a meeting house where, in 1639, he famously preached a sermon that inspired the Fundamental Orders, the framework by which Connecticut first governed itself. Later, the Fundamental Orders were incorporated into the royal Charter of 1662, which saw Connecticut through the American Revolution and into the founding of a new nation.

Over the years a series of public buildings replaced Hartford’s first meeting house. The first state house was built in 1720. By 1792 the general assembly decided to build a new state house in Hartford to honor the new nation. (Between 1717 and 1878 Hartford and New Haven were co-capitals. New Haven had a state house built in 1768 and would get a new one in 1831.) Painter John Trumbull wrote a letter to Oliver Wolcott Jr. expressing his desire for an “elegant and durable building” that would “tend to the Honor of the state.”

The completed building, designed by noted American architect Charles Bulfinch, suited the needs and peculiarities of Connecticut’s government. The legislative chambers sat on the second floor, literally above the courtroom and executive offices, reflecting a principal concept of Connecticut’s governance: that the executive and judicial functions answered to the legislature, which in turn answered to the people.

When it opened in 1796, the State House dominated Hartford’s central square. Inside and out, the building suggested a permanence to match the state’s stability. And yet, within those walls, the Standing Order, a group of elite men belonging to both the Congregational Church and Connecticut’s founding families who had controlled state government for generations, soon took missteps that led its political opponents to call for a constitutional convention that ended their rule. The Old State House was the site of the debates and decisions leading to the Constitution of 1818.

Calls for a change in leadership had been building since the presidential election of 1800 but during its May 1814 session in Hartford, the general assembly alienated Episcopalians by voting to deny them funds to charter an Episcopal college. Episcopal leaders expressed their frustration by joining Jeffersonian Republicans to form the Toleration (or Reform) Party. In the The Public Records of the State of Connecticut (vol. 17), editor Douglas Arnold identifies this misstep as a key factor in “the collapse of the Federalist Standing Order.”

That same year Connecticut’s Federalist leaders hosted New England delegates for the Hartford Convention, with a goal of ending the War of 1812. Gilbert Stuart’s portrait of George Washington watched over the proceedings in the State House’s senate chamber while the men created a list of proposed amendments to the United States Constitution. Designed to give New England more power on the national stage, the demands were backed with a thinly veiled threat of secession. The war came to an abrupt end before the demands could be presented to the U.S. Congress, leaving Federalist leaders looking like traitorous Anglophiles in a nation swept up in patriotic euphoria. (See “The ‘Notorious’ Hartford Convention,” Summer 2012.)

That embarassment led to election losses that further weakened the Federalists and empowered the Toleration Party. Once the new party controlled the general assembly and the offices of governor and lieutenant governor, the new leadership called for the state’s very first constitutional convention.

The convention convened at the State House in Hartford on August 26, 1818 and continued through mid September. Most towns sent two delegates, 201 in all, to engage in relatively productive and cordial proceedings.

Changes in governance led to changes in the building. The Governor’s Council became the senate, and its long history of private meetings ended with the constitution’s requirement that “debates of each house shall be public.” A public gallery was installed. The constitution also required that the governor and his cabinet to keep offices in the building. By 1820 the governor had a small office on the first floor.

Less than a decade later, Connecticut’s Old State House was hardly recognizable: the roof was replaced and a cupola, dome, and statue of Justice were added on top. The bricks were painted white. The building that for a short time celebrated the Standing Order had been changed drastically, marking an abrupt end to the state’s tradition of steady habits.

The building continued to be used until the present state capitol was built in 1871. For more information about Connecticut’s state houses, visit cga.ct.gov/hco/his-places.asp and see “Connecticut’s Old State House,” Fall 2004.

Jacob Orcutt is the coordinator of onsite services at Connecticut’s Old State House and holds an M.A. in history from UMass Amherst.

Connecticut Explored received support for this publication from the State Historic Preservation Office of the Department of Economic and Community Development with funds from the Community Investment Act of the State of Connecticut.

Connecticut Explored received support for this publication from the State Historic Preservation Office of the Department of Economic and Community Development with funds from the Community Investment Act of the State of Connecticut.