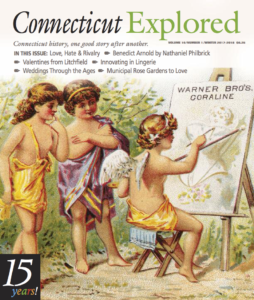

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Winter 2017-2018

The production of corsets and undergarments—those most intimate of underthings that we wear for comfort and hygiene or to improve our appearance—was a major industry in Connecticut and a leading source of factory jobs for women from the mid-19th to the mid-20th century. The industry was made possible by the availability of mass-produced textiles developed during the industrial revolution and the development by 1850 of practical sewing machines. Connecticut entrepreneurs perceived the possibilities these new technologies offered. By the third quarter of the 19th century the state produced large numbers of woolen and cotton underwear and hosiery and played an important role in the production of corsets.

By 1907, 19 companies in Connecticut manufactured knitted hosiery, both stockings and socks, and underwear for women, men, and children. These products were made on large knitting machines using wool, silk, and cotton. The companies were located throughout the state, but the largest were the American Hosiery Company in New Britain and the Winsted Hosiery Company in Winsted. Many began as hosiery-knitting factories and moved to producing knitted underwear such as long underwear, knitted shirts, and underpants for men and underpants and underdresses for women. The Bristol Knitting Company, for example, founded in 1850, was by 1882 the N. L. Birge & Sons Company specializing in men’s and children’s underwear.

The Winsted Hosiery Company opened in 1882 on the banks of the Still River. It produced hosiery and underwear and by 1936 was the largest producer of knitted undergarments in the state. Almost all of these factories produced union suits, the men’s one-piece long underwear now familiar to viewers of the television show Little House on the Prairie (1974 – 1984) or the 2003 film Cold Mountain. A women’s version, made in wool and cotton knit, was a slip-like underdress.

Some companies specialized. The Eastern Underwear Company in South Norwalk, for instance, produced goods only for women and children and the Nichols Underwear Corporation in the same city produced only muslin underwear.

Underwear

Underwear

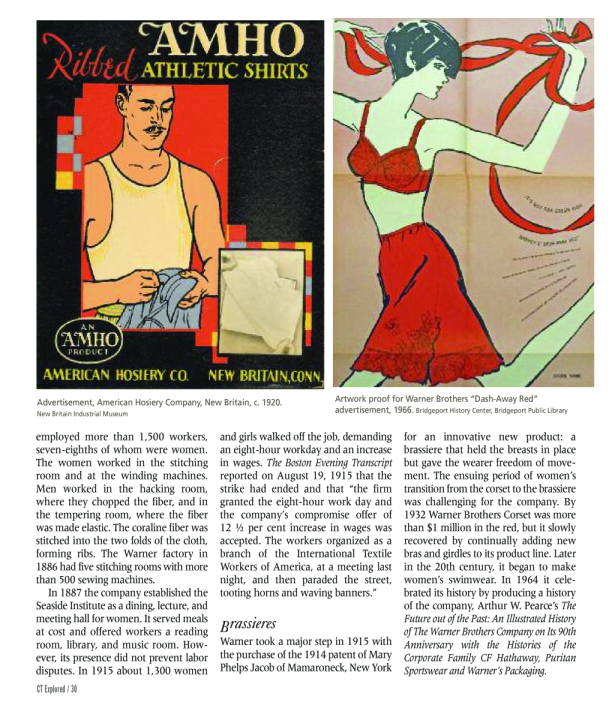

The American Hosiery Company in New Britain was founded in 1868 “to manufacture from wool, cotton, silk, flax or other materials or combination there in any or every description of goods which are or may be desired and to sell the same.” The company was formed to fill a demand for fine woolen underwear and to diversify New Britain’s Industrial base after the Civil War. One of the company’s first products was a very fine underwear made from soft Merino lambswool. The products were made for men, women and children. As part of a marketing campaign, they adopted the name AMHO and the slogan “Body Clothing Means Better Underwear.”

John Butler Talcott, one of the founders of the American Hosiery Corporation, was introduced to the knitting industry in 1853 while president of the New Britain Knitting Company. He imported machinery from England and a mechanic to operate the equipment at American Hosiery. He imported Merino wool from Australia and Egyptian and Sea Island cotton that was spun on the new machines.

American Hosiery won a number of awards. At the 1876 Centennial International Exhibition in Philadelphia, the company was commended for the “high standard of excellence in texture and finish, perfection in fashion and form.” By the 1920s the company tried to convince its customers that “Impressions count! That’s why men are particular about their outward appearance. And, as fine outer clothing impresses others, fine body clothing makes even a stronger impression on yourself.” Undergarments now had become more than just about warmth or coolness and comfort. They were self-expressions of status.

The early 1900s was a boom period for the production of underwear in Connecticut. Several companies added factory buildings and expanded their workforces. The Bristol Manufactory Company employed 150 workers in 1903. By 1907 N. L. Birge & Sons Company, also in Bristol, had 120 workers and a showroom and offices in New York City. The Winsted Hosiery Company added a six-bay extension to its factory in 1911.

Along with that growth came labor disputes. In 1901, 70 women went on strike over issues of pay and working conditions at the Alling Mill, also known as the Paugassett Mills, in Derby. After 54 days, Samuel Gompers, the president of the American Federation of Labor, came to Derby to help settle the strike and quickly negotiated an end.

Corsets

In the 19th century Connecticut’s whaling industry supplied the whalebone for corset stays. Workers worked primarily in their own homes and small shops and were paid by the piece. A private contract worker described the working conditions in a letter to the New Haven Union newspaper (August 6, 1871): The cut material was provided to the stitcher. After it was stitched, it was embroidered, boned, eyeleted, trimmed, bound, starched and ironed, laced, and packed. The stitcher was responsible for 48 rows of stitching on a single corset averaging a foot a row, and she had to purchase her own thread from the manufacturer. The stitcher made 85 cents per dozen corsets, and the wholesale price was about $10 per dozen. After a corset had gone through the many hands of production, the company made a profit of $5.65 per dozen.

That system soon changed. The Strouse, Adler Company was founded in New Haven in 1862 by Isaac Strouse and Max Adler, who were Bavarian Jews. They purchased a year-old corset company and developed it into one of the largest employers in New Haven. By 1877 the firm had outgrown its building and relocated to a large factory building on Olive Street in the Wooster Square neighborhood that had previously housed Winchester & Davies, a shirt manufacturer. Oliver Winchester had left the shirt manufacturing company to form the Winchester Repeating Arms Company.

By 1889 Strouse, Adler employed 1,200 workers in several five-story buildings. A description in the chamber of commerce-sponsored The Industrial Advantages of the City of New Haven, Conn. published in 1889 states that

The production of the house consists of corset and corset clasps of all grades and patterns, and in which the firm have no superiors in the world. These products are made from improved designs, each operation is performed with the utmost precision and accuracy, that the finished corset may be made adaptable to any figure. The workmanship is unexcelled, and the materials used are the best in the market. In the styles and patterns care is given to the laws of health, and there is no wonder that the ninety-five per cent of ladies now-a-days buys corsets manufactured for the trade instead of resorting to the more expensive work of custom methods, when such a perfect-fitting and beautiful corsets can be procured everywhere as those made by this firm.

Strouse, Adler’s corsets were in high demand among women who wanted to achieve the hourglass figure so popular from the mid-19th century to the early 20th century. The famous C/B corset a la Spirite (“C/B” stood for “100 bones,” the Roman numeral “C” for 100 and the “B” for bones made from the whalebone or baleen) was able to give most women a waist measuring between 18 and 22 inches around! At the end of the century the company introduced the “Watchspring” corset, which used sliding detachable spring steel rather than the traditional, fragile whalebone for stays. The corsets were warranted to never break and were made in several styles.

The company was able to produce high-quality foundation garments selling for $1.25 to $2.50, which made them affordable for most women. The Report of the Commissioners from Connecticut to the Louisiana Purchase Exposition in 1904 described the corset factory as occupying 132,425 square feet and producing 600 dozen corsets per day in nearly 500 different styles and sizes. The corsets were made of “Jeans, Coutils, Alexandria Cloth, Silk and Cotton Batistes, Silks and Satins.” The designs were overseen by a French corsetiere and made by a “very large force of experienced operatives employed in the thirty departments the corsets pass through to completion.”

Working conditions at the Strouse, Adler Company in 1889 were described in The Industrial Advantages of the City of New Haven. Max Adler, it said,

has introduced many novel features for the comfort and convenience of his employees, and he has discovered the means of obtaining faithful and superior service from a large force of the best and the most expert workers, and the good feeling that prevails between himself and his small army of helpers, is a credit to him and a matter of favorable comment.

Unfortunately, the workers did not have that same “good feeling.” On Saturday, February 8, 1890, the workers arrived as usual that morning, but the minute the superintendent entered one workshop, the 300 women there stopped running the machines. They quietly left their stations and the factory. The strike was called after the workers heard that in two days pay cuts were to take effect. For each worker who did piece-work the cut was between 20 percent and 40 percent. The pay of stitchers was reduced from $6 to $5 per week. The trimmers’ pay was cut by 40 percent and the lace binders’ by 59 percent. The company claimed that the cuts were necessary because of competition from plants in Massachusetts, New York, and New Jersey, where wages were lower. It threatened that 500 workers would lose their jobs if the factory had to move. The workers also protested the requirement that they supply their own needles and thread at a cost of about $2 per week and purchase them from the company store. The thread alone cost 33 percent more than at other stores in the city. The outcome of the strike is unknown. These exploited garment workers, almost all Italian, Jewish, or Polish women, would not have unions to protect their rights until the 1930s.

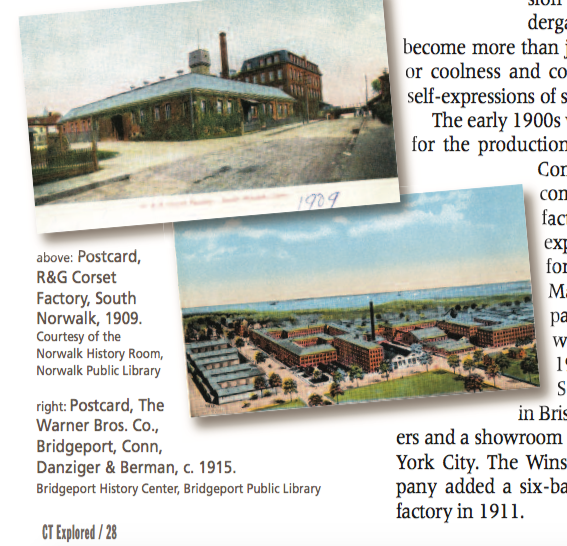

Brothers Ira DeVer Warner and Lucien Warner, whose company would become known as Warner Brothers and then Warnaco, began life as tailors in upstate New York before focusing on manufacturing corsets. They moved to Bridgeport in 1876 to expand their factory. They faced healthy competition in the city, but while Strouse, Adler was the largest corset factory in the 19th century, by the early 20th century Warner Brothers was on top. Through the 20th century, sales at Warner continued to increase as the company introduced innovative products. Combined, Connecticut factories manufactured three-quarters of the corsets in the United States in the early 20th century.

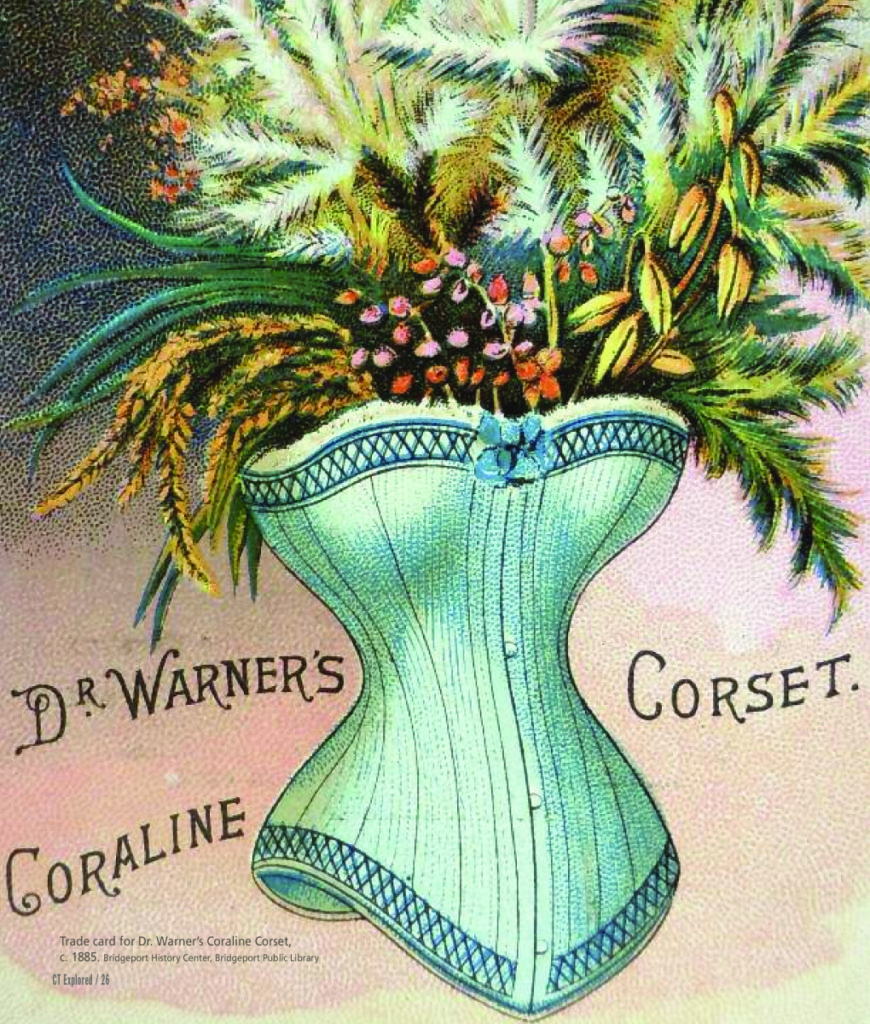

Ira and Lucien Warner were trained as doctors, and before entering the textile business they had ventured into snake-oil remedies under the name “Warner’s Safe Kidney and Liver Cure.” They became interested in developing a corset that was less constrictive than others on the market and named their product “Dr. Warner’s Health Corset.” One of their most successful corsets was the “Coraline.” It was manufactured in part with Tampico grass fiber, also called coraline, imported from Mexico. The grass becomes tough and elastic when heated and pressed, making it an ideal material for keeping the corset’s shape. By the late 1880s the company employed more than 1,500 workers, seven-eighths of whom were women. The women worked in the stitching room and at the winding machines. Men worked in the hacking room, where they chopped the fiber, and in the tempering room, where the fiber was made elastic. The coraline fiber was stitched into the two folds of the cloth, forming ribs. The Warner factory in 1886 had five stitching rooms with more than 500 sewing machines.

In 1887 the company established the Seaside Institute as a dining, lecture, and meeting hall for women. It served meals at cost and offered workers a reading room, library, and music room. However, its presence did not prevent labor disputes. In 1915 about 1,300 women and girls walked off the job demanding an eight-hour workday and an increase in wages. The Boston Evening Transcript reported on August 19, 1915 that the strike had ended and that “the firm granted the eight-hour work day and the company’s compromise offer of 12 ½ per cent increase in wages was accepted. The workers organized as a branch of the International Textile Workers of America, at a meeting last night, and then paraded the street, tooting horns and waving banners.”

Brassieres

Brassieres

Warner took a major step in 1915 with the purchase of the 1914 patent of Mary Phelps Jacob of Mamaroneck, New York for an innovative new product: a brassiere that held the breasts in place but gave the wearer freedom of movement. The ensuing period of women’s transition from the corset to the brassiere was challenging for the company. By 1932 Warner Brothers Corset was more than $1 million in the red, but it slowly recovered by continually adding new bras and girdles to its product line. Later in the 20th century, it began to make women’s swimwear. In 1964 it celebrated its history by producing a history of the company, Arthur W. Pearce’s The Future out of the Past: An illustrated History of The Warner Brothers Company on Its 90th Anniversary with the Histories of the Corporate Family CF Hathaway, Puritan Sportswear and Warner’s Packaging.

In 1968 Warner Brothers Company became Warnaco. Inc. and then the Warnaco Group, and it diversified by adding men’s and women’s sportswear and through aggressive mergers and acquisitions. It was now the parent company off Warner’s, Speedo, and Olga. In the late 1980s, Warnaco moved its corporate headquarters to New York City and relocated some staff to Milford, Connecticut. Most of the production moved overseas and a factory in Duncansville, Pennsylvania. In 2013 Warnaco was purchased by PVH, Phillips-Van Heusen, a clothing conglomerate based in New York City.

The End of the Underwear Industry in Connecticut

Strouse, Alder also found itself having to change with the times. In the mid-1950s the company used a new synthetic material, LYCRA™, in developing a foundation garment called the “Smoothie” girdle. The Smoothie was advertised as “so silky soft, so light and dainty, yet with the miraculous power of LYCRA™.” Unfortunately, the company did not survive a corporate takeover in 1994 by the holding company Aristotle Corporation and in 1998 Sara Lee purchased it and the factory closed its doors in 1999.

The underwear industry in Connecticut closed because of mergers and acquisitions in the clothing business and the move of its factories to areas with cheaper labor. Most corset companies closed because they did not diversify when the corset went out of style. A Connecticut example is the R & G Corset Company of South Norwalk. Founded by Emil Roth and Julius Goldschmidt in 1880, it was originally located on North Water Street, but by 1895 the company built a new factory on Ann Street. In 1901 it employed 1,000 workers and produced 650 dozen corsets daily. R&G’s stressed the comfort of its New Model 837 with the straightforward slogan “They fit. They wear. They hold their shape.” The company marketed widely, often buying quarter-page advertisements in popular ladies’ magazine such as Ladies’ Home Journal. The company is listed in the city directories through1929. The site was occupied from 1930 to 1935 by the Corsetry, Inc., which was probably a different and short-lived company.

Although the undergarment industry has left the state, its history lives on in the factories where those undergarments were manufactured. A number of these buildings, including those that once housed Strouse, Alder in New Haven, Warner Brothers in Bridgeport, R & G in South Norwalk, Winsted Hosiery in Winsted, and Kraus Corsets in Derby, have been retrofitted as apartments. Some even retain a painted advertisement, as the Smoothie Foundation Garments ad that remains on the side of the former Strouse, Adler factory, or the company name, such as R&G Corset Co., which remains on one of that company’s former buildings in South Norwalk, giving this important past industry a presence today.

Elizabeth Pratt Fox is a museum and historic-site consultant. She most recently wrote “The Gaiety of the Connecticut Cocktail Shaker” (Summer 2017).