By Jennifer LaRue

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Fall 2014

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

Any state in the Union would be proud to match tiny Connecticut’s prodigious role in the creation of books for young readers. From Maurice Sendak and William Steig to Gertrude Chandler Warner, Eleanor Estes, and Madeleine L’Engle, an impressive list of people who have written and/or illustrated seminal works of children’s literature have either been born and raised in Connecticut or chosen to move here as adults.

To be sure, one of the chief reasons authors and illustrators opt to live in Connecticut is its proximity to New York City and Boston, both major publishing hubs. But in the 19th century, Connecticut—and particularly Hartford—was itself home to a thriving publishing industry that produced many volumes of what were then considered appropriate books for children. The now-antiquated texts of that era gradually gave way to the less didactic children’s books of the mid-20th century, with Connecticut authors and illustrators among those making innovative, high-quality contributions to the field and earning children’s literature’s top honors, the John Newbery Medal for literature and the Randolph Caldecott Medal for picture-book art.

The evolution in children’s literature and in the way we regard books for young readers was guided in large part by Caroline Hewins, librarian at the Hartford Young Men’s Institute (now the Hartford Public Library) from 1875 to 1926, who pioneered the movement to make libraries kid-friendly. (See “Hartford’s First Lady of the Library,” Summer 2007.) In the preface to her 1915 Books for Boys and Girls: A Selected List (American Library Association Publishing Board), Hewins wrote, “The best books for a child are the books that enlarge his world,” and that when buying books for children, consideration should be given to “a child’s own likings most of all.” But Hewins did have specific standards as to what constituted proper reading for young people. For instance, she wrote, “Stories of the present day in which children die, are cruelly treated, or offer advice to their fathers and mothers, and take charge of the finances and love affairs of their elders, are not good reading for boys and girls in happy homes… .”

Here we spotlight a handful of children’s-book authors and illustrators, an influential editor, and a seminal children’s media production company with meaningful ties to Connecticut.

Peter Parley

Which way is Boston from the place you live in?

Which way is New-York?

Which way is Hartford?

Which way is Philadelphia?From the “Introductory Lesson. Questions to my little Reader” in Peter Parley’s Method of Telling About Geography to Children (Hartford: H. and F.J. Huntington, 1831)

Samuel Griswold Goodrich (1793 – 1860) built one of the first American children’s-book empires. In the early 19th century, Goodrich, writing as the kindly, story-telling older gentleman “Peter Parley,” was familiar to and beloved by young readers all over America and abroad. Historian Pat Pflieger (merrycoz.com/kids.htm) observes that he was “mobbed by children when he toured the [United States] South in 1846.” And in Europe, Goodrich’s (extensively pirated) work was so common a cultural touchstone that James Joyce saw fit to mention Peter Parley’s history books in his 1922 epic Ulysses.

Title page and facing frontispiece illustration of the book Right is Might, and Other Sketches by the author of Peter Parley’s Tales. (Hartford: H.H. Hawley & Co., 1850). The Connecticut Historical Society

Born in Ridgefield, from 1799 to 1803 Goodrich attended a tiny, rustic schoolhouse, where he received his only formal education. His experience with the books he encountered there—a mix of texts written for adults and terrifying nursery rhymes—along with his need to earn a living inspired him as a young man to create what he considered more suitable-—and saleable—texts for the next generation.

As children’s literature scholar Leonard Marcus notes in Minders of Make-Believe (Houghton Mifflin Company, 2008), Goodrich’s grandfather Elizur Goodrich “is remembered as the friend who urged Noah Webster to write an American dictionary.” Though familiar with Webster’s Blue-Backed Speller, Goodrich learned to read from Thomas Dilworth’s A New Guide to the English Tongue and according to Pflieger, “he thought Webster’s book was better.” (See “Father of American Copyright Law,” page 43.)

Goodrich wrote, co-wrote, or edited about 170 volumes, including more than 40 Peter Parley publications. A number of his works were published in Hartford, including his The Youth’s Arithmetic, published by Huntington & Hopkins in 1819, and Peter Parley’s Book of Fables, published by White, Dwier & Co. in 1836. His New York Times obituary said his textbooks “introduced a class of books which have since become universal.”

The Ridgefield Historical Society maintains the schoolhouse, now named for Peter Parley, as a museum. See Explore!, below.

The Story of Ferdinand’s Illustrator

Father had come from Kentucky many years ago, and his talk of the bluegrass had become just a trifle tiresome. “’Twon’t grow good here,” Porkey interrupted, “’twon’t grow good here in Connecticut at all.” Rabbit Hill

Robert Lawson (1892-1957) is the only person to have won both the Caldecott Medal (in 1940, for They Were Strong and Good) and the Newbery Medal (in 1944, for Rabbit Hill). His contributions to children’s literature are many and lasting: He wrote and/or illustrated more than 70 children’s books, finding early success creating art for Leaf Munro’s The Story of Ferdinand (1936) and later crafting books such as Ben and Me, one of several in which he allows a historical figure’s tale to be told by a close-friend animal.

Lawson and his wife Marie Abrams, also an illustrator, moved from his native New York City to Westport in 1923, but financial troubles soon sent them back to the city. They returned to Connecticut a few years later, though, to a rural farmhouse, just outside Westport, that they called Rabbit Hill. Lawson’s 1944 children’s novel of that name, which he also illustrated, is about a community of animals living near an abandoned farmhouse and the changes that occur as new people move into the house. As the map Lawson drew for the book’s endpapers notes, Rabbit Hill is situated near a road that leads “up Danbury way.”

Cover, The Carrot Seed by Ruth Krauss, illustrated by Crockett Johnson (Harper & Row, c. 1945). Reproduction courtesy of Archives & Special Collections, UConn Libraries at the Thomas J. Dodd Research Center

The Carrot Seed and More

Space restrictions prohibit our doing justice here to the contributions author Ruth Krauss (1901-1993) and illustrator Crockett Johnson (born David Johnson Leisk, 1906-1975) made not just to children’s literature but to American culture in general. Husband and wife, Krauss and Johnson lived in the Rowayton section of Norwalk throughout their prolific careers and moved to Westport toward the end of their lives; the ashes of both were scattered over Long Island Sound. They were key members of the thriving arts community in Rowayton in the 1950s, and their influence remains strong today.

Krauss wrote dozens of books, including The Carrot Seed (1945; illustrated by Johnson) and A Hole is to Dig: A First Book of First Definitions (1952; illustrated by Maurice Sendak). As biographer Philip Nel notes of Krauss in Crockett Johnson and Ruth Krauss: How an Unlikely Couple Found Love, Dodged the FBI, and Transformed Children’s Literature (University Press of Mississippi, 2012), “Krauss’s influence has been so pervasive as to have become invisible: Contemporary readers take for granted that there have always been vital, spontaneous, loose-tongued children in children’s books. There haven’t.” Of Johnson’s 1955 masterpiece Harold and The Purple Crayon, Nel says, “[The book] has captivated so many people because Harold’s crayon not only embodies the imagination but shows that the mind can change the world: What we dream can become real, nothing can become something.”

The Witch of Blackbird Pond

The story of Kit Tyler is entirely fictitious. The house in which the Wood family lived, and all the adventures which took place there, existed only in imagination, but old houses much like it can still be seen in Wethersfield, one of the first settlements of the Connecticut Colony. The Great Meadows still stretch quietly along the river, and a relic of an old warehouse marks the once thriving river port. – from the Author’s Note, The Witch of Blackbird Pond

Elizabeth George Speare’s New York Times obituary does not mention Connecticut. That’s quite an omission, given that Speare (1908-1994) lived in Wethersfield for many years, beginning in 1936, and cast the town as the setting for perhaps her most enduring novel, The Witch of Blackbird Pond (1958). Wethersfield’s landscape, architecture, and history—particularly its pre-Salem witch trials [See “Wethersfield’s Witch Trials,” Winter 2007/2008.]—informed her tale of Connecticut Colony drama set in 1687.

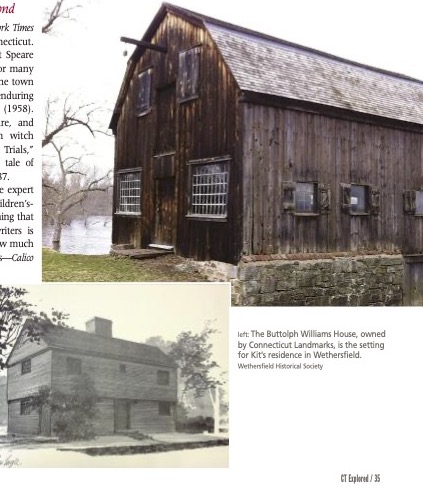

top: Cove Warehouse Maritime Museum, located at the north end of Main Street in Warehouse Park, interprets the maritime history of Wethersfield. The Warehouse is mentioned in The Witch of Blackbird Pond when Kit originally arrives in Wethersfield and walks up Main Street to her aunt and uncle’s house. bottom: The Buttolph Williams House, owned by Connecticut Landmarks, is the setting for Kit’s residence in Wethersfield. Wethersfield Historical Society

According to children’s literature expert Anita Silvey, writing in her “Children’s-Book-a-Day Almanac” blog, “One thing that distinguishes Speare from other writers is how few books she created—and how much acclaim they all received. Four novels—Calico Captive, The Witch of Blackbird Pond, The Bronze Bow, The Sign of the Beaver—and one work of nonfiction, Life in Colonial America, constitute her entire output. Yet for these five books, she won two Newbery Medals and one Newbery Honor, a record of excellence unsurpassed by others.” Oh, by the way? Speare wrote them all while living and raising her family—in Connecticut.

An Editor and the Authors She Nurtured

“Good books for bad children” – Ursula Nordstrom

“The luckiest kid on the block….” – Maurice Sendak, on his weekends in Rowayton with Ruth Krauss and Crockett Johnson

Maurice Sendak (1928-2012) may be the author/illustrator whom Connecticut is most proud to claim. Born in Brooklyn, New York in 1928, Sendak moved to Ridgefield in 1972, having publishing his groundbreaking, Caldecott Medal-winning masterpiece Where the Wild Things Are in 1963. The remote farmhouse he shared with his long-time partner Dr. Eugene Glynn and the views from his workshop were classic Connecticut, though it is unclear the extent to which those surroundings influenced his work, as the books he is best known for were published before he moved here.

But Sendak’s association with Connecticut residents Ruth Krauss and Crockett Johnson was instrumental in guiding his career—as was his relationship with his editor Ursula Nordstrom (1910-1988), who in 1950 lured him away from his job as a window-dresser for F.A.O. Schwartz and encouraged him to devote himself to illustrating books. Nordstrom, director of Harper’s Department of Books for Boys and Girls from 1940 to 1973, nurtured the careers of many of children’s literature’s other leading lights, from E.B. White and Margaret Wise Brown to illustrator Garth Williams and author/illustrator Shel Silverstein. She took Sendak under her wing and nursed him through his insecurities; she introduced him to Krauss and Johnson, at whose home he spent many weekends in Rowayton during the 1950s. In his biography of the couple, Philip Nel quotes Sendak’s description of their “old-fashioned white house with a porch, with the water there, and Dave had a sailboat. Well, you can imagine how I felt. Like the luckiest kid on the block.” Sendak notes that the pair “became my weekend parents and took on the job of shaping me into an artist….”

Nordstrom moved to Bridgewater in the mid-1970s with her partner Mary Griffith. As Leonard Marcus reports in Dear Genius (HarperCollins, 1998), his collection of Nordstrom’s letters, Nordstrom liked to say she published “good books for bad children.” Her monumental contributions to the body of literature for young people include her fostering of Louise Fitzhugh’s work.

Louise Fitzhugh (1928-1974), a Memphis native who like many other authors and illustrators landed in New York City, bought a home in Bridgewater, Connecticut in 1969. She is best remembered for her landmark novel Harriet the Spy (1964), which celebrates its 50th anniversary this year. Her next book was The Long Secret (1965). Nordstrom recalls in a letter written to her correspondent Joan Robins (included in Dear Genius), “I remember clearly the day I read the manuscript… . And came upon the part devoted to Beth Ellen’s first menstruation. I wrote in the margin, ‘Thank you, Louise Fitzhugh!’, for it seemed to me it was about time that this subject…was mentioned naturally and accepted in a children’s book as a part of life.”

But the relationship between Nordstrom and Fitzhugh eventually cooled. “As you know,” Nordstrom wrote to Robins, “we didn’t publish her last book, or two, but it was just one of those inevitable misunderstandings that do occur once in a while between one who is a genius, and the most devoted editorial staff. Anyhow, it ended up that we both, unbeknownst to each other, bought houses in Bridgewater… and we met one day by accident … and there was a rapprochement and happiness and emotion on both sides.”

The Cricket in Times Square

“I guess I’m just feeling Septemberish” sighed Chester. “It’s getting towards autumn now. And it’s so pretty up in Connecticut. All the trees change color. The days get very clear―with a little smoke on the horizon from burning leaves. Pumpkins begin to come out.” – Chester Cricket, The Cricket in Times Square

George Selden (George Selden Thompson, 1929 – 1989) was born in Hartford, attended the Loomis School, and earned a bachelor’s degree at Yale. He then moved to New York City. His Newbery Honor-winning novel The Cricket in Times Square (1960) features a cricket named Chester who finds himself in the Times Square subway station after being carried aboard a commuter train in a picnic basket. Chester adapts to city life with the help of friends he meets in the subway station, including a mouse named Tucker and a cat named Harry, but after a summer in the city he yearns to return to the country. His friends see him off at Grand Central:

How will you know when you get to Connecticut?” said Tucker. “You were buried under sandwiches when you left there.”

“Oh, I’ll know!” said Chester. “I’ll smell the trees and I’ll feel the air, and I’ll know.”

Selden wrote six sequels, beginning with Tucker’s Countryside (1969), which is set in the pastoral imaginary town of Hedley, Connecticut. A 1997 Amazon customer review of the book says, “I read it in fifth grade about 5 times. I’m 18 years old and still remember the book. Ever since I read it I’ve wanted to visit Connecticut and eat Liverwurst. I tried the liverwurst and it wasn’t too good. I still want to visit Connecticut though.”

Weston Woods Studio

We will seek the best books from all over the world and adapt them in such a way as to preserve the integrity of the original. By doing so, we will help children discover the riches that are trapped between the covers of the books and motivate them to want to read for themselves. – from the Weston Woods Studios mission statement

He is neither a children’s-book author nor an illustrator. But it’s hard to overestimate the role Morton Schindel has played in connecting young readers (or readers-to-be) with books. In 1953, Schindel, working from his log-cabin home in Weston, Connecticut, and inspired by reading to his own young children, founded Weston Woods Studio (named for the woods surrounding his cabin) to produce audiovisual adaptations that “bring outstanding children’s picture books to life.” Since then the studio, enlisting the talents of such distinguished animators as Gene Deitch and Michael Sporn, has produced more than 500 films, filmstrips, and videos, which it distributes (now through Scholastic, which bought the studio in 1996) to libraries, schools, and directly to consumers. Weston Woods films were screened at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City in 1956 and debuted on CBS’s Captain Kangaroo show that same year. The studio, which moved to Norwalk in 2001 and has branches in the United Kingdom, Australia, and Canada, continues to create live-action and animated versions of children’s-book favorites, including titles by Connecticut author/illustrators Maurice Sendak, William Steig, and Tomie dePaolo.

Jennifer LaRue is the editor of Connecticut Explored. Her picture book The Beginner’s Guide to Running Away From Home (Random House/Schwartz & Wade) was included in The Best Children’s Books of the Year, 2014 Edition by the Bank Street College Center for Children’s Literature.

Explore!

Read more stories about Connecticut’s art & literary history on our TOPICS page

Read more stories about childhood in Connecticut on our TOPICS page

Read more stories about Notable Connecticans on our TOPICS page

Peter Parley Schoolhouse

The small schoolhouse in which Samuel Griswold Goodrich received his only formal education is open to the public the last Sunday of each month from 1 to 4 p.m. It is located off Rt. 35 at the corner of West Lane and South Salem Road. Ridgefield Historical Society, peterparleyschoolhouse.com, 203-438-5821

The Witch of Blackbird Pond

Wethersfield was named a Literary Landmark by the Friends of Libraries USA for its role as the setting for Witch of Blackbird Pond. Find a brochure showing sites related to the story at wethersfieldlibrary.org/about/townhistory.html.

The Cove Warehouse, Wethersfield Historical Society, wethhist.org

The Buttolph-Williams House, a Connecticut Landmarks property operated by the Webb-Deane-Stevens Museum, webb-deane-stevens.org or ctlandmarks.org/content/buttolph-williams-house

Rowayton and The Purple Crayon

A special exhibition, Rowayton and the Purple Crayon: Celebrating the Creative Culture of 1950s Rowayton, is on view through November 2014 at the Rowayton Historical Society, 177 Rowayton Avenue, Rowayton. rowaytonhistoricalsociety.org, 203-831-0136

More About Children’s Books

The 23rd Annual Connecticut Children’s Book Fair, November 8-9, 2014, in the Rome Ballroom on the Storrs Campus, University of Connecticut, celebrates children and the books they read. Admission is free. bookfair.uconn.edu, or contact co-chairs Suzy Staubach, 860-486-8525, or Terri Goldich, 860-486-3646.

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!