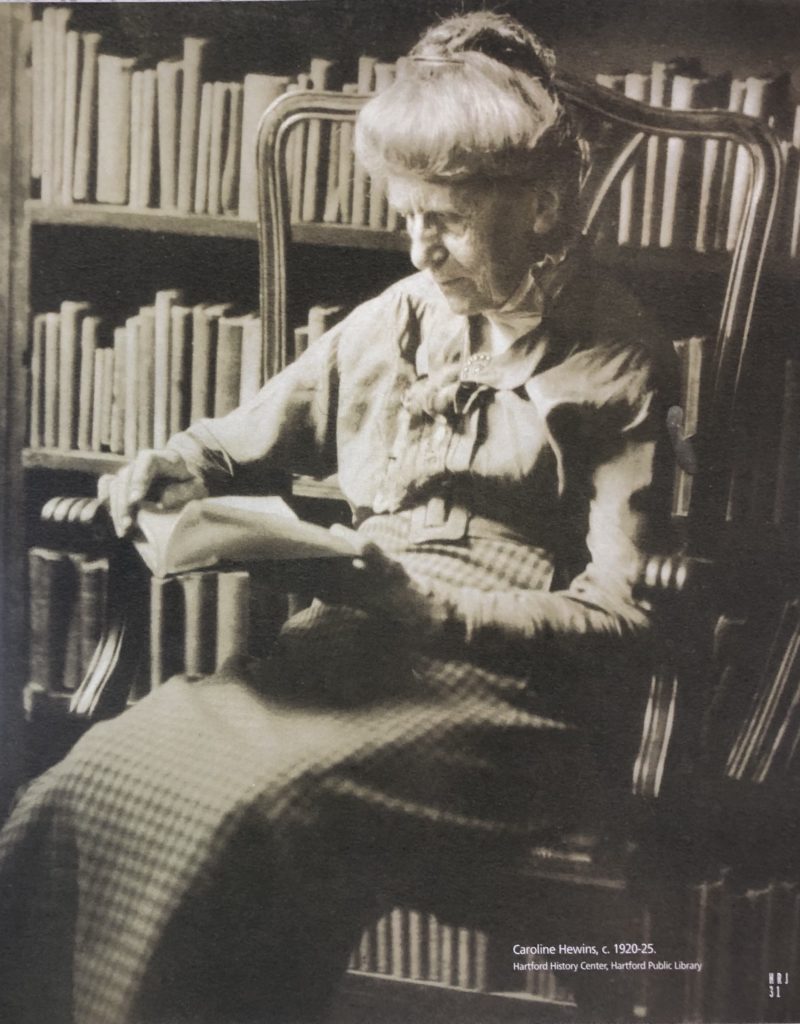

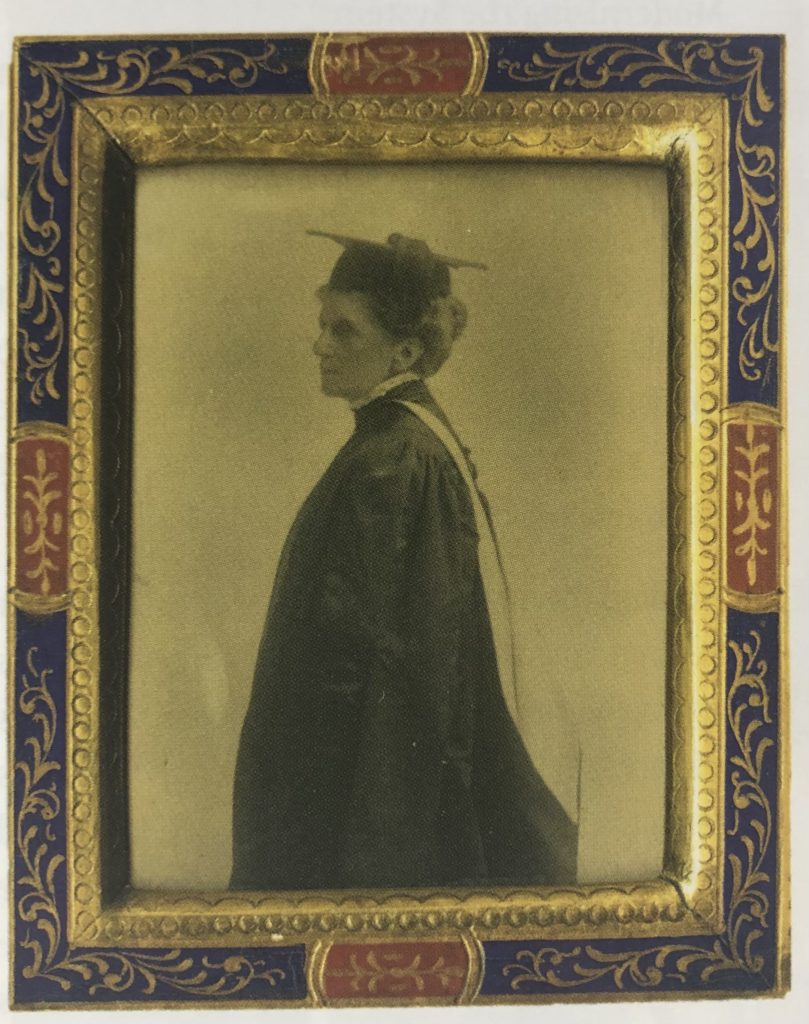

In 1911, Hewins became the first woman to receive an honorary Master of Arts degree from then-all-male Trinity College, Hartford. Hartford History Center, Hartford Public Library

By Susan Bivin Aller

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Summer 2007

Subscribe/Buy the issue!

When 29-year-old Caroline Hewins arrived in Hartford from Roxbury, Massachusetts in 1875 to become librarian of the Young Men’s Institute, she was but modestly equipped for her job: her experience included a few years of teaching school, some volunteering in a small-town library, and a year of work at the prestigious Boston Athenaeum. But during her life-long tenure in Hartford, this young woman, with her contagious enthusiasm for children and for libraries, rose to national prominence in the field of library services for children, establishing influential standards and practices for putting books in young readers’ hands.

Caroline Maria Hewins was born in Roxbury in 1846. Her wealthy father founded the Boston haberdashery Hewins & Hollis, which later merged into the now-defunct Filene’s department store. Caroline and her eight younger siblings lived with her parents, two aunts, an uncle, a grandmother, and a great-grandmother. In her memoir A Mid-Century Child and her Books, published the month of her death, Hewins noted that she had learned to read by the time she was four, “but I do not remember the process…. I have no knowledge of a time when the words in an ordinary printed book and the marriages, deaths and accidents in the Boston Evening Transcript were beyond my powers of pronouncing and understanding.”[i]

Most children in the 1840s and 1850s had access to books from three main sources: apprentices’ libraries (collections of books on a range of topics that were set up and supervised by older businessmen for use by apprentices and others), schools, and church Sunday schools. Only a fortunate few, like the Hewins children, had books of their own at home. Caroline lovingly describes the first book she ever owned: Jacob Abbott’s Lucy’s Conversations, in which “Lucy has croup in the night and the next morning is given a powder in jelly and a roasted apple that was cooked by hanging it in front of the fire from a string held by a flatiron on the mantelpiece.”[ii] Hewins kept this slim volume for the rest of her life.

The books Caroline read as a child influenced her life’s work to a great extent. They included the traditional canon of British classics and the American novelists of her day. But she also read widely from Greek, Roman, and other European literature, and from fairy and folk tales of many nations. In the last 20 years of her life, she attempted to re-create (and eventually exceeded) her childhood library, becoming an avid collector known well by second-hand booksellers. She rationalized this love affair by insisting that she merely wanted to compare the beloved older volumes with what modern children were reading. In the end, she amassed a collection of more than 4,000 books—the Hewins Collection—now preserved at the Connecticut Historical Society Museum and the Hartford Public Library.

After graduating from the Girls High School and Normal School of Boston in 1862, Caroline taught school, then worked for a year at the Boston Athenaeum, where the eminent librarian William Frederick Poole trained and inspired her. It was then she decided to devote her life to the library profession. She got her big career break when the Young Men’s Institute Library in Hartford hired her as its librarian.

Modernizing the System

The Institute, housed in the 33-year-old Wadsworth Atheneum along with the Connecticut Historical Society, two other libraries, and an art collection, was a holdover from the days of subscription libraries. The city had then a population of about 50,000, of whom perhaps six hundred were subscribers to the library, paying three dollars for the use of one book at a time or five dollars for two, including admission to the periodical room.[iii]

Weeding the collection, buying worthy books for children, and shelving the children’s books separately from the adult books became Hewins’s primary concerns as she tried to raise her library’s standards. One day a boy asked her for bound volumes of the Police News and a thriller called The Murderer and the Fortune Teller. “These are not in the library and will not be!” she fumed.[iv] The library’s directors agreed that she could discard (even burn) books that she deemed “full of profanity and brutal vulgarity.”[v]

She extended the reach of her work into Hartford schools, lending them books and setting up a small independent library at the North Street Settlement House (part of a reform movement wherein residents—precursors of today’s social workers—lived among the urban poor and tried to help them), where she lived with a friend for 12 years. She opened it one hour every night for her neighbors.

In 1878 the Young Men’s Institute was absorbed by the Hartford Library Association. Ten years later, following a large challenge gift by J. Pierpont Morgan, the Wadsworth Atheneum was remodeled, leading to expanded quarters for Hewins’s library and eventually to the funding that enabled the Institute to become the free Hartford Public Library in 1892, with independent governance by a self-perpetuating corporation.

A year earlier, Hewins founded and became executive secretary of the Connecticut Public Library Committee (forerunner of the state library commission) and for the next 10 years traveled by horse and buggy to small towns throughout the state, encouraging cooperation between libraries and schools for the benefit of children. She arranged for state-wide traveling libraries and book deposit stations at schools, factories, and settlement houses, setting the stage for today’s modern branch library system.

“To encourage a love of reading in boys and girls”

The American Library Association (ALA) was founded in 1876, and Hewins was an early member. Her initial claim to fame in that organization was as the first woman to address its national conference from the floor. Her question: “How many libraries use their dog tax for books?” [vi] She soon became known for her authoritative papers on library management and for her visionary leadership in children’s work.

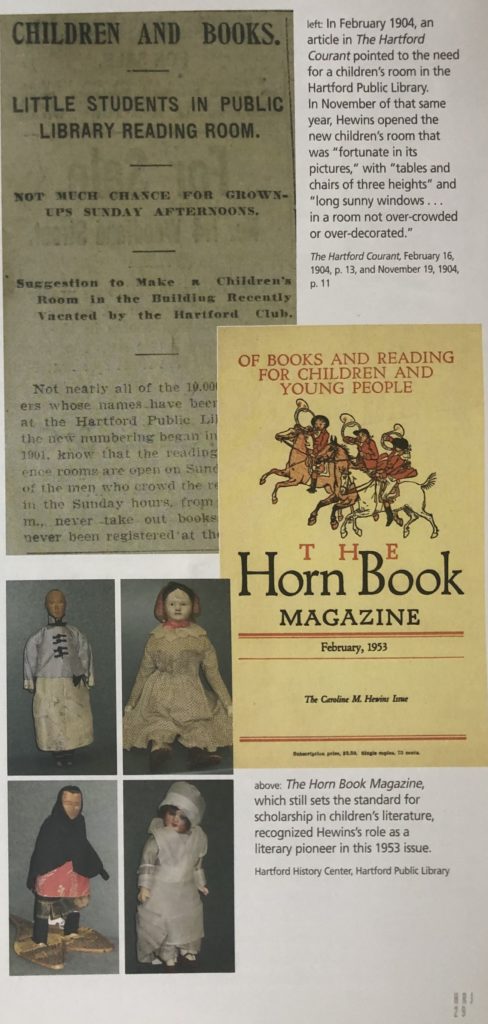

Top: The Hartford Courant, February 1904. Center, right: The Horn Book Magazine recognized Hewins’s role as a literary pioneer, 1953; bottom left: dolls Hewins collected and shared. Hartford History Center, Hartford Public Library

In 1882, Hewins sent a questionnaire to 25 of the country’s leading libraries, asking, “What are you doing to encourage a love of reading in boys and girls?” Based on the not-so-encouraging answers, she gave an impassioned report on children’s work to the ALA. This was a watershed moment. Within a few years, the ALA had established a children’s division and was on its way to supporting professional training schools for children’s librarians. Also in1882 she published Books for the Young, the first bibliography designed for children, and in 1888 she published a history of children’s books in the Atlantic Monthly.

Although Hewins was chief administrator of the entire, growing city library—an exceedingly rare position for a woman in those days (though she had many female friends in the field, none were heads of libraries)—she always paid special attention to young people. With her flair for the dramatic and a great sense of humor and enthusiasm, she provided experiences they would never forget. She wrote plays for them to perform, organized reading clubs, led Saturday nature walks, and conducted story hours.

The increase in the number of children using the library’s reading room put pressure on the library’s board to grant a separate room for them, but the board was slow to act. Ever on the lookout for a good dramatic moment, Hewins played her trump card in 1904: a newspaper photo showing patrons in the reading room on a Sunday afternoon. In the photo are one man, one woman—and fifty-one children. (Whether Hewins arranged to have the photographer there remains a mystery.) The trustees soon found two large, sunny rooms in an old house next door to the Atheneum that had coincidentally been vacated by the Hartford Club. Suddenly, Hewins had her children’s department. Well-intentioned friends sent decorative furnishings to supplement the child-sized chairs and tables. Notwithstanding the eclectic mix—a cuckoo clock, 50 Japanese prints of chrysanthemums, a pair of andirons, a Boston fern, a case of stuffed birds, and two trunks of curiosities from Europe, Asia, and Africa—the new children’s department became a cheery center for good reading and good times.

When some libraries were still posting signs on their doors barring children and dogs, Hewins welcomed both in her library. One particular dog apparently was a pet of the library. He kept watch near the front door, checking on patrons as they came and went. One day Hewins and a group of children decided this friendly animal needed a name, so they put out several bowls of dog food. On each bowl, Hewins wrote a name or short phrase. Whatever was written on the bowl he ate from would be his name. The one he chose said “Moreover, the dog….” (The Biblical passage describing a dog’s licking Lazarus’s sores reads “Moreover, the dog licked….” and has become a bit of a Bible joke: “The only dog called by name in the Bible: Moreover.”) So he was named Moro.

During her summer vacations, Hewins often went abroad, sometimes accompanied by a favorite nephew. She sent letters to the children of Hartford, which were published in the local newspaper. They are charming accounts of the places she visited, enlivened by references to books, paintings, sculptures, natural wonders, and other subjects her children might have learned about from her at the library. These letters were published as A Traveler’s Letters to Boys and Girls by The Macmillan Company in 1923.

On her journeys she bought dolls in every country to add to her collection in the children’s room at the library. There, every New Year’s Day, Hewins held a reception for little girls and their new Christmas dolls. The party ended with tea and cakes. Today, her doll collection is occasionally exhibited at the Hartford Public Library—in the spacious new children’s room.

A Literary Pioneer

Among her closest friends was Anne Carroll Moore, who established the children’s room at the New York Public Library in 1906. Moore patterned her library after Hewins’s room in Hartford. In the 40 years she supervised children’s work in New York, Moore worked tirelessly to develop a standard literary criticism for children’s books that would elevate their standing in the eyes of the book world. Another friend of Hewins and Moore was Alice Jordan, head of children’s work at the Boston Public Library and a pioneering professor of children’s literature at Simmons College. Bertha Mahoney Miller, a student of Jordan’s, founded the Bookshop for Boys and Girls in Boston, stocking it with books from Hewins’s list of recommendations. Later, Miller founded The Horn Book Magazine, which still sets the standard for scholarship in children’s literature.

By 1919, it had become evident to the publishing industry that children’s books represented a lucrative market—and that librarians held the key to that market. In that year, The Macmillan Company opened a children’s division; three years later, Doubleday Page & Company followed suit. Many of the first children’s editors were recruited from the ranks of children’s librarians.

On October 10, 1926, Caroline Hewins celebrated her 80th birthday. She was still active at the library. In honor of her 51 years of service, the Hartford Librarians’ Club established a scholarship fund to assist young women who wanted to train for children’s work in public libraries. In late November, Hewins carried on her long-standing tradition of going to New York City to participate in Halloween festivities at the New York Public Library, which were led by her friend Anne Carroll Moore. She also wanted to meet with her publisher at Macmillan and check the final proofs on her book, A Mid-Century Child and Her Books (with its affectionate introduction by Moore). Hewins had recently suffered a bronchitis attack that prevented her from attending an ALA conference in Atlantic City. The exertions of the New York activities further weakened her, and on returning to Hartford she fell ill with pneumonia. Four days later, on November 4, 1926, Hewins died at her home at 190 Sigourney Street in Hartford.

At her funeral in Center Church, small children, elderly men and women, civic leaders, and librarians from all over New England came to pay her tribute. A blanket of violets from her co-workers at the library covered the casket; the children of the North Street Settlement House sent a large bouquet of rosebuds, and Moore brought a wreath of roses with oak leaves. Dr. Rockwell Harmon Potter delivered the eulogy, calling her “a great public servant.” “We give thanks for a half century of service,” he said. “Let the city cherish the gift.” Hewins was buried in her family’s plot at Dedham, Massachusetts.

From today’s bustling and high-profile world of children’s libraries and book publishing, almost all roads lead back to Caroline Hewins and her work in Hartford. In her 51 years in Hartford, Hewins formed or participated in most of the library and education-related organizations in Connecticut and in a number of civic and cultural clubs. In 1951 she was one of 40 librarians named to the Library Hall of Fame; she was inducted into the Connecticut Women’s Hall of Fame in1995. In 1911, Trinity College awarded her a Master of Arts Honoris Causa—making her the first woman to be so honored by the then-all-male college. At the conclusion of the ceremony, college president Flavel S. Luther took off his hat to her. “Hail, first daughter of Trinity,” he proclaimed.

Susan Bivin Aller is the author of numerous biographies for young people, an essayist, and a book collector. She is chair of the advisory council of the Connecticut Center for the Book.

[i]. Hewins, Caroline M., A Mid-Century Child and her Books (New York, Macmillan, 1926), p. 16.

[ii]. Hewins, p. 50.

[iii]. Hewins, “How Library Work with Children Has Grown in Hartford and Connecticut,” The Library Journal, February 1914, p. 2.

[iv].Hewins.

[v]. Hewins.

[vi]. Root, Mary E. S., “As It Was in the Beginning: Caroline M. Hewins, lover of children,” Public Libraries, 30:246 (May 1925).

Explore!

Read more stories about Notable Connecticans on our TOPICS page.

Read more stories about Childhood on our TOPICS pages.