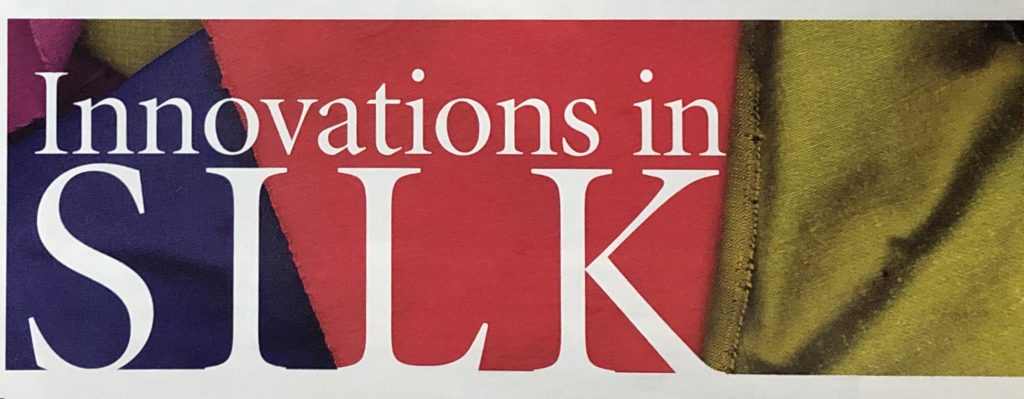

Ribbon loom weaving tubular silk neckties, Silk Industry So Manchester, Conn., 1914. Thirty ties were woven at one time in long strips like ribbons. As the strips of ties came from the shuttles, they were wound on the drums seen in the lower part of the picture. These strips were then removed and cut into lengths suitable for neckties. Private collection.

By Charles B. Fears

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Spring 2005

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

The Cheney Brothers Company of Manchester, Connecticut, at one time the premier silk textile manufacturer in North America, represents one of New England’s early innovators. The resident family of Cheneys not only introduced critical innovations in textile manufacturing machinery during the company’s existence, but also in their factory management methodologies, product marketing and design, industrial relations policies, and personnel management. Many of their policies would become common practice in American industry by the end of the first quarter of the 20th century. Throughout the company’s existence the Cheney family’s principal residences remained in Manchester, as did the main weaving mills and expanded factory system, all near the company’s original mill.

In 1838, fifteen years after Connecticut incorporated the town of Manchester — then a small agricultural community located just east of Hartford — four of eight Cheney brothers (Ward, Frank, Rush, and Ralph) and Edwin Arnold founded the precursor to Cheney Brothers Company: the Mount Nebo Silk Manufacturing Company. The Cheney brothers had moved into the manufacture of silk thread after failed ventures in New Jersey, Connecticut, and Ohio, where they had attempted to cultivate mulberry trees and silk worms (sericulture). The Cheneys, long-time residents of Manchester, had entered the silk trade in its early stages in the United States. In fact a viable world finished wilk market did not develop until the last half of the 19th century, when manufacturing techniques advanced in western Europe and a widening demand for silk permitted its production in economically significant amounts. The production of raw silk increased sharply in China and then Japan in tandem with the expanded markets for finished silk products. [See also, “Connecticut’s Mulberry Craze,” Summer 2010,]

The Cheneys improved silk manufacturing methods early in the company’s history. In 1847 they patented the first practical machine for making sewing silks (silk thread). In the mid-1850s, the family developed a process that enabled the firm to use much of the waste from cocoons previously discarded, thereby yielding more product from the same amount of raw materials, and in 1855 produced a spooling machine that allowed one operator to manage three machines simultaneously. During the early 1860s the Cheneys adopted the use of power looms shortly after their introduction in Switzerland. Thereafter, the company began producing the broad silk cloth used in women’s fashions, and adopted innovations in dyeing technology, the production of velvets, and other manufacturing techniques – all of which resulted in a broader range of finished products.

Already by May 1860 Charles Cheney (another Cheney brother, he joined the company after its founding) had written enthusiastically to his son Frank Woodbridge Cheney (then on a buying trip in the Far East) of the prospects for weaving silk cloth:

The [weaving]product is very satisfactory and promises to quite eclipse the sewings and twist. The demand is almost unlimited at present. We are making experiments in weaving other broad goods, and have no difficulty in adopting the power looms to almost anything. The field for such an enterprise is very large and as yet unoccupied.

The evolution of Manchester, Connecticut into a company town involved the creation of a unique form of paternalism and pervasive social control under the direction of the Cheney family. The company expanded with the conviction, characteristic of the times, that they had chosen the most efficacious route to prosperity and success by becoming a part of the new industrial economy. An article on the company appearing in the November 1872 issue of Harper’s New Monthly Magazine observed that “it is unquestionably a fact that the industrial advance of the last seventy years has been a most necessary and important step in social evolution.” The entrepreneurial spirit that drove family members to seek increasingly more efficient means of production from the company’s founding strongly influenced the company’s policies toward employees and their community. The family changed the name from Mount Nebo to Cheney Brothers Silk Manufacturing Company in 1854, by which time the Cheney family owned 100 percent of the company. In 1873 the company became Cheney Brothers Company.

As early as 1872, the popular press (Harper’s New Monthly) described Manchester as a “workers’ utopia.” Eighteen years later, Harper’s Weekly, in its February 1, 1890 issue, reported, “At South Manchester, in Connecticut, there is what, in many respects, is the most attractive mill village in the country, one of the most delightful villages in New England.” Manchester’s reputation a s a model town continued into the 20th century, when Budgett Meakin described South Manchester as one of the “most idyllic” of industrial villages to be found in the U.S., in Model Factories and Villages his 1905 survey of U.S. industrial towns. Meakin noted the good quality of workers’ housing in a park-like surrounding. [See “Cheney Brothers: Life in a Mill Town.” Spring 2004.]

By the end of the 19th century, the Cheney Brothers Company had become a world leader in the manufacture of quality silk textiles. They also represented one of a handful of fully integrated silk textile manufacturing concerns in the United States. Their operations extended from the direct importation of raw silk from the Far East, to the final end product, silk cloth of the highest quality.

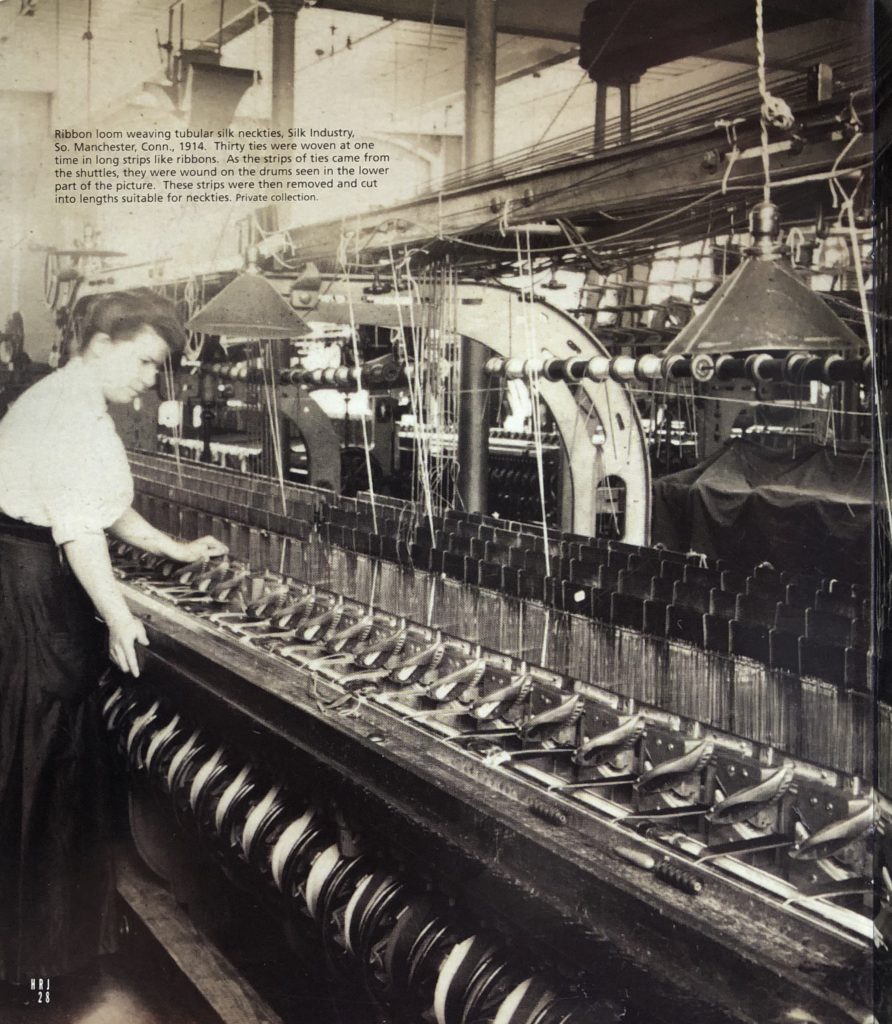

top: “Beaming off,” the winding of silk threads onto a “loom beam.” The beam held the warp thread on the weaving loom. Beaming off required attendants to watch carefully to ensure threads did not become tangled or crossed. 1914. Private collection. bottom: Making flags, Cheney Brothers, c. 1918. photo: W. F. Miller & Co. Connecticut Historical Society Museum, Hartford

SCIENTIFIC MANAGEMENT AT CHENEY BROTHERS

In the early years of the 10th century, the third generation of Cheneys, seeking to maintain the company’s dominant position in the silk manufacturing business, contacted the leaders of emerging factory management methods. Two of Frank Woodbridge Cheney’s sons (most likely Horace B. and Charles Cheney) met with Frederick Winslow Taylor during the spring of 1911 to discuss his scientific management techniques. Taylor’s methodology combined a new manner of wage payment, stop-watch time studies, and new management techniques. He sought not only to “get employees to work harder but to control the entire job situation, and standardization became the primary means of achieving control.”[i] The Cheneys made a strong impression on Taylor. Referring them to his principle disciple at the time, Henry L. Gantt, Taylor described the Cheneys as model business owners.

I had here yesterday about the finest set of men who have ever been here, the two Cheneys, who are at the head of the great silk industry, the largest in the world, employing 3,000 or 4,000 men at South Manchester, Conn. They have a non-union plant, treat their employees admirably, and have a great deal of piecework and are altogether a very fine company.[ii]

In 1912 the Cheneys hired Gantt to utilize Taylor’s theories to introduce “improved methods in the shop management, cost system and stores accounting of the Company” as part of a “’Scientific Management’ campaign.”[iii]

Taylorism, as scientific management was known, suited the Cheneys’ desire to control the factory system. Horace Cheney expressed his interest as “the continual research to discover whether the methods in use could not be improved in some manner which would result in greater product being made with less effort and better quality, in higher wages, or in anything which might be considered an advance in industry.”[iv]

The Cheneys applied the “development of the science,” the most important element of Taylor’s new management philosophy, to the production of silk. This refers to analyzing a manufacturing job on a logical, or “scientific,” basis, i.e., gathering all technical and other information held by the workers, and formulating rules and procedures to optimize workers’ performance. They Cheneys broke down each function into distinct steps for both worker and machinery, determining the skills and worker characteristics required to carry out every aspect of a given function, analyzing these components in unity, and then applying time-management techniques to each segment of a job. Under Gantt’s guidance, the company also changed its cost accounting method to more accurately determine and control the cost of producing its broad range of silk textiles. Perhaps most significantly, the company refined the process of selecting, training, monitoring, and retaining factory workers. The Cheneys devoted considerable effort to this aspect of industrial relations, customizing the hiring process to meet the needs of the company’s operations. More selective hiring criteria ostensibly would lead to greater ease in controlling the quality and composition of the company’s workforce.

In 1910 the company set up an employment department, before such offices became an integral part of corporate structures in the U.S. businesses. The following year the Cheneys hired a prominent Princeton University professor as a consultant to improve their hiring process – more effectively matching prospective employees with specific jobs. The Cheneys produced four hiring specification manuals, one for each major division within the company’s factory system. The manuals contained detailed job descriptions and photographs of factory jobs from the mundane, such as an elevator operator, to the most demanding, the skilled weavers. Job applicants reviewed these manuals at the employment office on the factory grounds. For those who did not speak or read English well enough to understand the requirements of a particular job, a company representative pointed to the photographs associated with the function. The applicate would indicate his or her familiarity or lack thereof with that occupation. After allowing the candidate to examine the worksite, he or she underwent a medical examination.

The Cheneys required applications for clerical, research, executive and other non-factory labor positions (approximately 10 percent of the total workforce) to take an intelligence test. Horace B. Cheney voiced his approval of the use of such tests in the hiring of clerical and administrative staff, noting in a letter that the results were “highly satisfactory. We did succeed unquestionably in testing intelligence, and the result of these tests, and the actual success and performance of duty, had a high correlation.” But he had a less favorable opinion of intelligence testing when it came to workers on the factory floor: “We have been unable to develop any correlation whatever in the remotest degree between the success of a man in operating a machine, and the degree of intelligence which we supposed he had.”

The company also established a division to oversee time-measurement studies in the factory. The Cheneys and other advocates of scientific management believed that the time-measurement analysis would lead to a resolution of what manufacturers perceived to be “wage problems” of the early 20th century. Factory managers felt that when they paid workers on an hourly basis, the workers did not produce as much as was reasonably expected within the time permitted. Conversely, when managers paid workers on a piecemeal basis (number of units produced), workers would limit their efforts for fear that managers would reduce the amount paid per unit if they produced too much.[v] Under ideal conditions and with scientific management, when the factory manager had the full cooperation of workers and a thorough understanding of each job, the optimal rate of production per worker achieved would lower the total labor cost per unit of production while increasing factory workers’ gross pay. With scientific management methodology, the piece rate per hour would increase incrementally with an increase in the rate of production, so both the company and the worker benefitted. This system permitted the company to more effectively control the costs of production.

The Cheneys further modified Gantt’s payment system through the use of their “credit rating plan.” This plan adjusted pay rates according to nonperformance related criteria (citizenship, property ownership, residency in Manchester, fluency in English, voter registration) which also reflected their efforts to reduce turnover in the workforce and Americanize immigrant workers.

Gantt’s wage payment plan, as modified by the Cheneys, eventually became a major source of discontent for workers. In 1923 workers’ complaints arose from the implementation of timekeeping methods to regulate workflow and levels of production and a brief walkout ensued. In a nod to the need for worker representation, Cheney Brothers formed a company union called the Works Councils in the same year, a common practice among manufacturers to thwart the encroaching influence of independent unions. The tactic succeeded in keeping independent unions out of the company for the next 11 years.

Besides scientific management, the Cheneys incorporated two other significant reforms in business management in the first two decades of the 20th century: employee benefits and personnel management. The formalization of employee benefits offered by the company in the first decade of the 20th century appears to have been in reaction to worker discontent and also to lessen the appeal of unionization by outsiders. In addition to adopting benefit plans found throughout the industrial sector later in the century, the Cheneys also incorporated the emerging bureaucracy of big business. An organization chart from the early 1920s shows a detailed breakdown of the company’s structure with eight departments, each with multiple layers of management below that. Cheney sons (typically graduates of Yale) held all but one of the department head positions. While technological advancements developed both within and outside the company fostered its expansion, Cheney Brothers Company maintained its entrepreneurial character by limiting managerial positions to family members.

By the end of the 19th century, Cheney Brothers had begun to move beyond the practices of other New England mill towns and stood at the vanguard of U.S. industry by instituting progressive welfare policies. The company maintained a medical and dental staff on the factory grounds, established a program for employees similar to a workman’s compensation arrangement, and in 1916 opened a day nursery for workers’ children. The company paid the equivalent of 25 percent of workers’ contributions into the Benefit Association of Cheney Brothers as well, and covered the Association’s operating expenses. The Association, founded in June 1910, provided for pension benefits and insurance “against accidents, sickness, death and old age.” This represented one of the earliest such comprehensive employee benefits organizations in the country. Company policy provided for payments of up to $500 to an employee or members of his or her family when “not adequately provided for by the state’s workmen’s compensation laws or the Benefit Association of Cheney Brothers.”[vi] By 1914 more than three-quarter of Cheney Brothers employees belonged to the Association.

ADVERTISING THE CHENEY VISION

The Cheneys begrudgingly accepted the need to become more fashion-conscious regarding the design of their silks as they recognized a need to increase demand. The public relations consultant Edward L. Bernays (considered the father of public relations in the U.S.) believed their reluctance reflected the family’s New England roots: “The Puritan spirit undoubtedly played a part in curbing their interest in style and fashion. But their disdain for women contributed too. Conventional designs, they thought satisfied the public’s needs.”[vii] With a growing realization of the need to encourage consumer demand for the company’s stylish silk textiles and the role of advertising in that effort, the company began spending substantial sums for advertising after the turn of the century. Advertising expenditures steadily increased each year, aside from a modest decline during World War I, from $50,000 in 1910 to $250,000 in 1923.[viii]

Characteristic of the Cheneys’ business practice, once they focused on a particular strategy, they moved aggressively. The Cheneys hired the French industrial art designer Henry Creange from Alsace Lorraine as the company’s art director shortly after World War I. Creange subsequently enlisted the services of Bernays as public relations consultant. Bernays worked for the Cheney Brothers from 1923 to 1927, and under his guidance the company asserted its position as the leading U.S. producer of quality innovative silks.

Bernays arranged for the oldest long-term Cheney factory worker to present a piece of Cheney silk for a state dress to First Lady Florence Harding at the White House, an event reported in the newspapers.[ix] Following the well-publicized Tutankhamen discoveries in Egypt, he persuaded the Cheneys to award a scholarship to Hazel Slaughter, a young woman from Brooklyn, New York. Slaughter traveled to Egypt and, upon returning to the U.S., designed silk textiles with an Egyptian influence for the Cheneys. In 1927 the artist Marc Chagall inspired a new line of Cheney printed silks bearing floral designs. At an opening of his works at an art gallery in New York City, the paintings were draped with some of those same silks. Again with Bernays’ guidance, Cheney Brothers Company commissioned paintings from Georgia O’Keefe, incorporating innovative colors found in Cheney silks. Leading department stores such as B. Altman and Lord & Taylor’s in New York, and Marshall Fields in Chicago exhibited the paintings and Cheney silks in their display windows side by side. In 1925 the company received industrywide acknowledgement for the quality and design of its silks, winning awards at the International Exposition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Art held in the Louvre in Paris, France.

By 1927, Bernays proved instrumental in positioning the Cheneys at the forefront of fashion: “Cheney Brothers, the stodgy old New England firm, became Cheney Brothers, the great fashion house that combined the best features of Paris and New York.”[x]

Consumers typically requested products manufactured with Cheney silks during these years as a result of their advertising efforts and reputation for quality products. According to Bernays, the Cheney family “despite their traditions, now accepted the principle of organized public relations,” and established a public relations committee within the company.

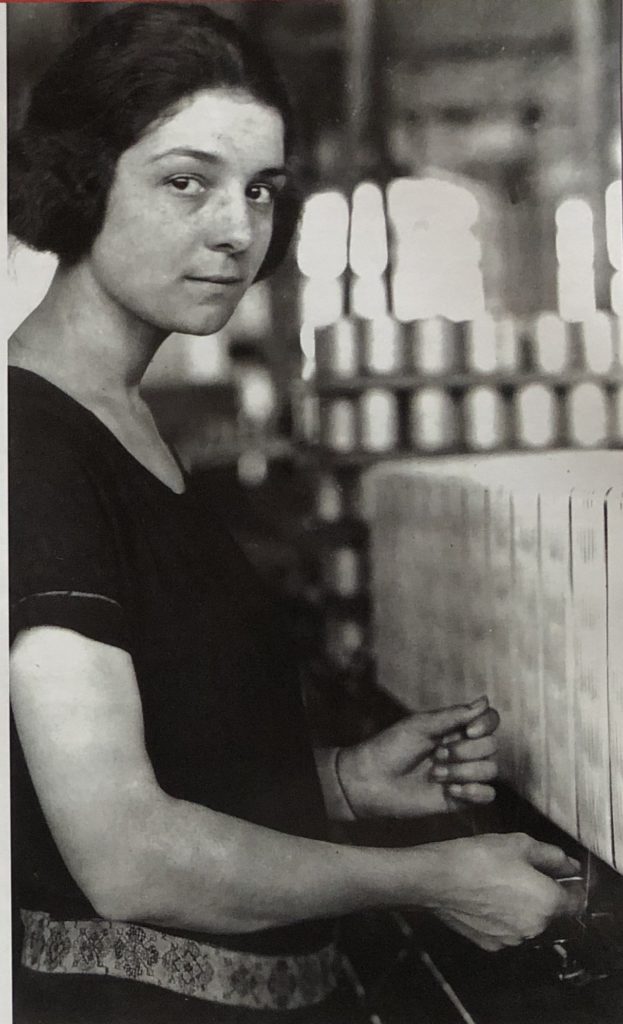

“Cheney Silk Mills. Favorable working conditions. Location: [South Manchester, Connecticut]” 1924. photo: Lewis Hine,

National Child Labor Committee Collection, Library of Congress

By the late 1920s the Cheney Brothers Company’s performance had begun a decline that would see only a few short-lived reversals in spite of the Cheneys’ more aggressive advertising and public relations efforts. Although the company’s peak earning year occurred in 1923 with revenues of $23 million, the fortunes of the textile industry as a whole had begun to decline before the Depression. Competition from rayon and nylon lessened consumer demand for silk, as did fundamental changes in women’s fashions. Moreover, the family continued to focus on high-end silk products despite the commoditization of silk, even while the senior Cheneys recognized that consumers now rarely asked for Cheney silks by name. A sharp decline in the price of raw silk from $20 a pound in 1923 to $1 a pound in 1931 aggravated Cheney Brothers’ financial situation as the value of the company’s inventory of raw silk fell precipitously, creating a financial deficit. Furthermore, in the early 1930s the federal government sharply reduced tariffs on imported silk textiles exacerbating the domestic silk industry’s financial predicament. The company could not overcome the economic and market pressures of escalating labor costs, competition from artificial textiles, and changing fashions. By 1934 Cheney Brothers Company’s annual advertising budget had shrunk from the peak of $250,000 just ten years earlier to a tenth of that amount. Responding to an inquiry from an advertising firm Cheney Brothers had worked with in the past, Horace Cheney wrote “We are doing almost no consumer advertising…. Identity has almost disappeared from the trade… price being the dominant factor.” The Cheneys found themselves burdened with the cost of maintaining plant facilities well in excess of the company’s manufacturing needs. They also chose not to move their operations to the southern U.S. in pursuit of cheaper nonunion labor. Companywide unionization came peacefully to Cheney Brothers in March 1934, but a strike that same year signaled a turning point in the relationship between family management and the workers; the company’s deteriorating financial condition could no longer support the myriad benefits previously provided to employees. Simply, the Cheneys’ paternalistic philosophy was unable to deflect the increasing depersonalization of the 20th-century factory system. The company’s performance continued to decline until 1954, when the Cheney family sold the company to J. P. Stevens Company for $4.8 million.

Over the span of its existence, the Cheney family aggressively sought to increase the efficiency of their business through the adoption of emerging scientific management methodologies, more refined hiring practices, and progressive industrial relations practices within a modern bureaucratic structure. Unfortunately, the gains realized from scientific management methodologies as a means of increasing manufacturing efficiencies while ameliorating worker discontent fell short of expectations. Yet the Cheneys and other manufacturers experiences a measurable improvement in their operations as advertising and public relations came to play a greater role in stimulating demand for their products in tandem with technological advancements in manufacturing. The Cheney Brothers Company record not only in Connecticut but in the U.S. stands as one of innovation, inventiveness, and entrepreneurship.

Charles Fears is a freelance writer, career financial services professional, and recent graduate of the M.A. history program at Brooklyn College in Brooklyn, New York. This article was based on his master’s thesis and includes subsequent research. This article was based on his master’s thesis and includes subsequent research.

Explore!

“Connecticut’s Mulberry Craze,” Summer 2010

“The Cheney Company Housing Auction of 1937,” Spring 2013

“Destination: Cheney Hall,” Fall 2002

“Cheney Brothers: Life in a Mill Town,” Spring 2004

Read more stories about products made or invented in Connecticut on our TOPICS page.

Footnotes:

[i] Merritt Roe Smith, forward, Scientific Management in Action: Taylorism at Watertown Arsenal, 1908-1915, Hugh G. J. Aitken (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1985), vii.

[ii] Frederick Winslow Taylor to Henry L. Gantt, May 10, 1911. Correspondence, Collection of Frederick Winslow Taylor, Samuel C. Williams Library, Stevens Institute of Technology, Hoboken, New Jersey.

[iii] March 12 & 30, 1912, Minutes, Box 3, Subseries A, Series I: Administrative Records (1734-1968), Cheney Brothers Silk Manufacturing Company Records, 1734-1997, Archives and Special Collections, Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut Libraries, 136, 138.

[iv] Horace B. Cheney, “An Appreciation of Henry L. Gantt,” Industrial Management 60(1): 406.

[v] Horace Bookwalter Drury, Scientific Management: A History and Criticism (New York: AMS Press, 1922) Studies in History, Economics and Public Law, 65(2), 53-55, 81.

[vi] March 3, 1914, Minutes, Box 3, Subseries A, Series I: Administrative Records (1734-1968), Cheney Brothers, Dodd Research Center, 235.

[vii] Edward L. Bernays, “Edward L. Bernays Papers. Typescript on Art in the Fashion Industry, 1923-1927: Cheney Brothers,” Prosperity and Thrift: The Coolidge Era and the Consumer Economy, 1921-1929. American Memory: Historical Collections for the National Digital Library, American Memory from the Library of Congress. http://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/r?ammem/cooll:@field(DOCID+@lit(me01)) (November 19, 2004)

[viii] March 4, 1913. Minutes, Box No. 3, Subseries A, Series I: Administrative Records (1734-1968), Cheney Brothers, Dodd Research Center, 186.

[ix] “1924: Recognition through Collaboration: Art in Industry,” The Museum of Public Relations. http://www.prmusuem.com/bernays-1924.html(November 19, 2004)

[x] Bernays, 8, 13. http://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/r?ammem/cooll:@field(DOCID+@lit(me01)) (November 19, 2004)