by Mary M. Donohue

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. SPRING 2013

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

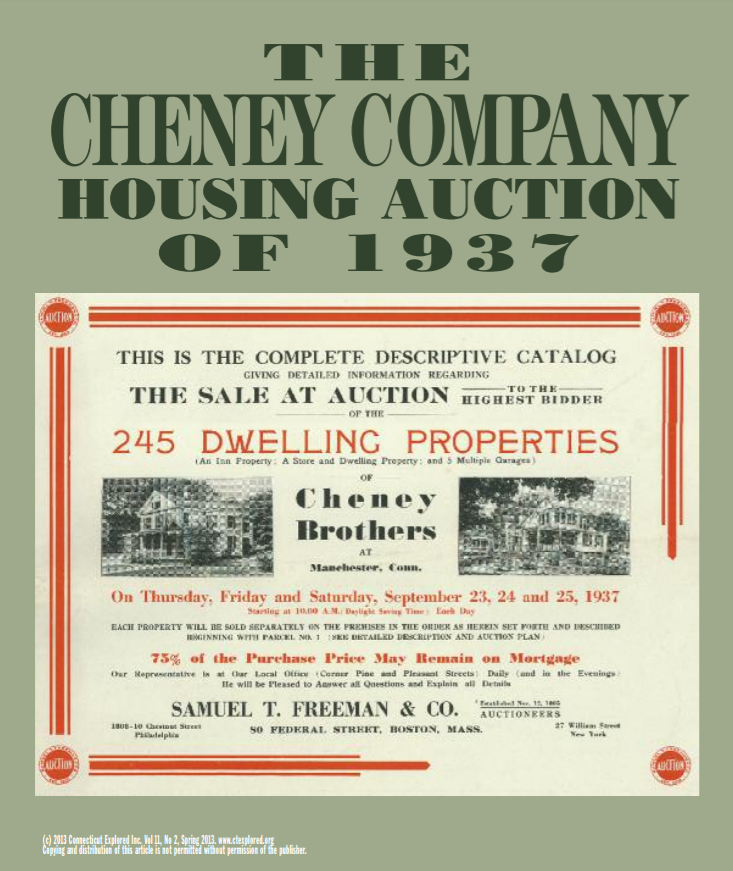

Mill towns were often owned by a single company, which would build and manage housing, stores, schools, parks, libraries, social halls, banks, and utilities. For more than 100 years, these industries thrived, but in the Great Depression of the 1930s, dozens of companies across the state were forced to shed their non-industrial real estate in order to receive federal bankruptcy protection and loan assistance. For the Cheney Brothers Silk Company of South Manchester, Connecticut, that meant selling 245 residential properties in a three-day auction in September 1937. Remarkable documentation of this public auction survives, including a descriptive auction catalog with fine-grained information about each property, photos, and newspaper articles chronicling each day’s sales prices and the crowd’s reaction, along with individual memories of this community milestone.

Mill Villages, Planned Industrial Developments, and Worker Housing

The practice of providing employee housing began in earnest at the end of the 18th century in industrial towns along the East Coast. Architectural historian Gwendolyn Wright, in Building the Dream, A Social History of Housing in America (The MIT Press, 1983), citesthe early 19th-century community of Paterson, New Jersey, as an early example. Francis Cabot Lowell and the Boston Manufacturing Company built large-scale textile mills in Waltham and Lowell, Massachusetts from the 1810s to the 1830s. They employed young unmarried women from nearby farms and housed them in wooden and brick boardinghouses. Earlier, in 1793, Samuel Slater’s textile mill in Pawtucket, Rhode Island, considered the first successful water-powered spinning mill in the country, used a different strategy. The “Rhode Island system” encouraged whole families—men, women, and children—to become factory employees. Connecticut primarily adopted the Rhode Island system of housing families. Wright notes, “In Rhode Island and Connecticut, factory owners erected rows of almost identical cottages. The regularity and uniformity strengthened the image of an orderly, utopian industrial development…”

Beginning in the 18th century, before the advent of electricity, Connecticut’s fast-running streams were dammed and their waterpower used by mills of all types. Over time, eastern Connecticut became associated with textile production featuring wool, cotton, and silk, and central/western Connecticut with precision manufacturing of metal products, from guns to buttons. To entice workers, mill owners began to provide employee housing.

Connecticut’s mill villages and worker housing have been extensively researched and documented in the Statewide Historic Resource Inventory of the State Historic Preservation Office, and many of these mill communities have been listed as historic districts on the National Register of Historic Places. But no comprehensive guide to the types and styles of worker housing across the state yet exists.

Two of Connecticut’s “model industrial communities” have been designated as National Historic Landmark Districts: “Coltsville” in Hartford and the Cheney Brothers Silk Company in South Manchester. A National Historic Landmark must be nationally significant and possess exceptional value in illustrating or interpreting the heritage of the United States. Both districts include important examples of worker housing.

The National Historic Landmark nomination written by Bruce Clouette for Coltsville documents Samuel Colt’s gun-making empire south of downtown Hartford. According to Clouette, “Colt set about building a large, steam-powered factory, housing and social facilities for workers, and his own mansion, Armsmear. He wanted to establish a planned industrial community in an urban setting.” To attract and retain skilled workers, he built several types of housing including brick, multi-family tenements (1850s) and a group of Carpenter Gothic, two-family cottages collectively known as “Potsdam Village” (1859).

Cheney Employee Housing

The Cheney Brothers Silk Company (see “Life in a Mill Town,” Summer 2004, and “Innovations in Silk,” Spring 2005) grew from a small family business to become one of the largest producers of silk in the country. Beginning in the 18th century, the Cheney family farmed in Manchester and managed a gristmill and sawmill. Having become interested in the silkworm craze that hit Connecticut in the 1830s (“Connecticut’s Mulberry Craze,” Summer 2010), they built the Mount Nebo Silk Mill in 1838. Although not initially successful, the family persevered, developing innovative machinery and production practices. By 1860, Cheney Brothers had locations in Hartford and Manchester and 600 employees. The Hartford mill was constructed in the 1850s in response to what the Hartford Daily Courant in an article dated August 14, 1908 called “the unwillingness of the [Irish immigrant] workers to live in the country.”

The Cheneys, however, continued to build their principal industrial complex near their family homestead in South Manchester. In 1880, the Hartford Daily Courant called South Manchester the “ideal manufacturing village,” observing that the Cheneys “…have built a large number of cottages on the place, which they let to married employees at a low rent. They have established boarding-houses for the unmarried… The cottages are each supplied with water, gas, and a pleasant garden plot.” Cheney Brothers employed carpenters, painters, and plumbers who could be assigned to work on the mill buildings and the owners’ mansions or to build employee rental homes. Although always part of the town of Manchester, South Manchester developed as a geographically compact industrial community dominated by the Cheney mills, which had almost 5,000 employees by 1916.

In 1916 the firm published an unusual 63-page recruiting manual called The Miracle Workers in five languages. Widely distributed in Europe, the heavily illustrated booklet extolled the healthy environment in South Manchester and all of the community assets the firm provided. Photographs of typical five-or six-room worker cottages, double-family homes, and much larger, single-family superintendents’ residences with rents ranging from $6 to $50 per month, were featured. “There are no tenement blocks in Manchester. Everybody lives in a house with a nice yard on a pleasant street,” the booklet observed.

In addition to making rental properties available to employees from the 1860s on, Cheney Brothers promoted homeownership and went to great lengths to assist employees with the purchase process, helping them buy houses the firm had built or moving them out of company-owned rentals in to privately built houses elsewhere in town. From about 1913 to 1916, 241 homes, the majority o f them two-family houses, were built and financed through the Manchester Building & Loan Association, founded in 1891 and supported by the Cheneys. The two-family “double house” provided a practical way for workers to purchase a home: The owner could live in one unit and rent the other for $15 to $22 per month. The clear path to homeownership was no doubt an important employee recruitment tool, and homeownership also helped the firm build a stable workforce.

On August 23, 1920, The Hartford Courant ran an article headlined “Eyes of the Nation on Cheney Bros. Work in Welfare Lines.” It crowed, “South Manchester is Model Manufacturing Community—Home Gardens, Dental Clinic” and “Company Builds Homes, Takes Over Boarding Houses, Provides Three Doctors.” The article detailed progressive services such as daycare and medical care that were provided for workers. But it also reported a dearth of homes for new employees. New neighborhoods on the east and west sides of South Manchester were planned to accommodate those needing housing; The Courant reported, “The houses constructed here have won the commendation of national groups interested in more beautiful homes.” Many of these homes were ultimately included in the 1937 auction.

The Bottom Falls Out

Cheney Brothers’ fortune was at a high point in 1923, with sales topping $23 million. By 1931, sales fell to $10 million as the nation slid further in to the Great Depression. The silk empire faltered. As noted in the district’s National Register nomination, “The decline… was primarily due to competition from the new synthetic fabrics, which were much cheaper to produce, but overproduction was also a factor. The company, which had always maintained high inventories of raw silk and finished goods, suffered substantial losses when the bottom fell out of the silk market. In just three months in 1929, the value of goods on hand dropped by $6 million.”

Labor costs and the slashing of tariff protections against foreign competition further crippled the company. In 1934, the firm had to secure a large loan from the Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC), a Roosevelt-era federal agency set up to provide emergency financing for agriculture, commerce, and industry. Referred to as a “lender of last resort,” in 1937 the RFC required the Cheneys to reorganize, and, according to William Buckley in The History of Manchester, Connecticut (Pequot Press, 1973), ordered the firm to sell all of its tenant houses.

The 1937 Auction

Company president Ward Cheney chose the auction firm of Samuel T. Freeman & Co., established in 1805, to conduct the sale. (Today, Freeman & Co. is strictly a fine art auction house.) During the Great Depression, the firm had “a record of more than one hundred similar sales of groups of mill-owned dwellings in New England behind it…” according to the Cheney Brothers sales catalog (1937). When the Rossie Velvet Mill in Mystic, Connecticut, closed its doors in 1937, for instance, Freeman & Co. auctioned off the mill contents and real estate.

In the sales catalog, Ward Cheney put the sale in a positive light, describing it as part of the firm’s modernization. Great care was taken to assure employees that the sale would be fair and that the final price would be decided by the highest bidder, not set in advance by the company. Cheney further stated that mortgage financing of up to 75 percent of the purchase price was assured to every buyer, a continuation of the company’s commitment to helping its employees become homeowners.

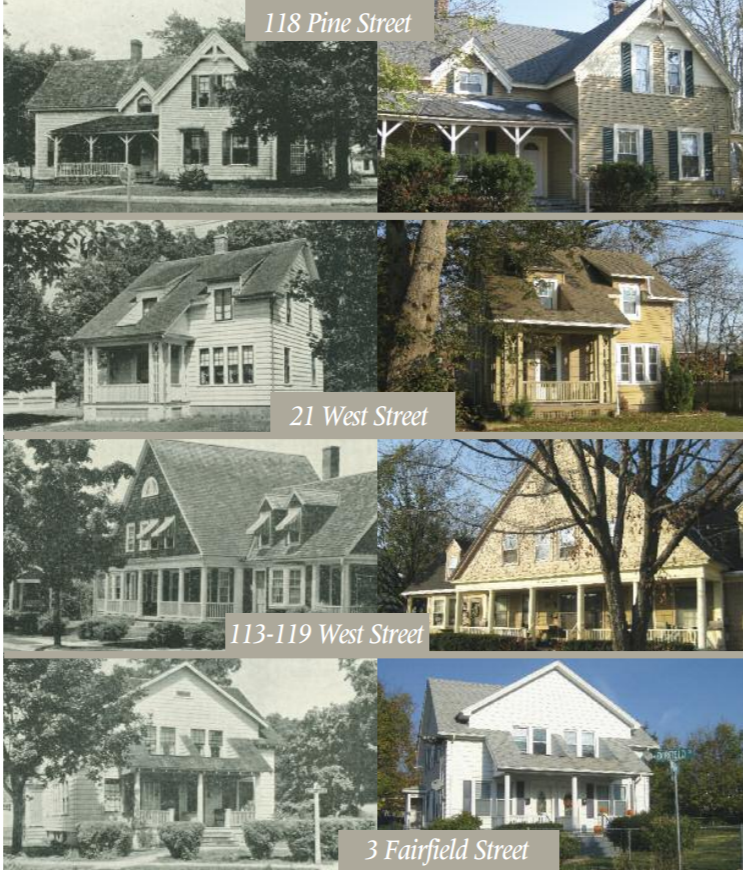

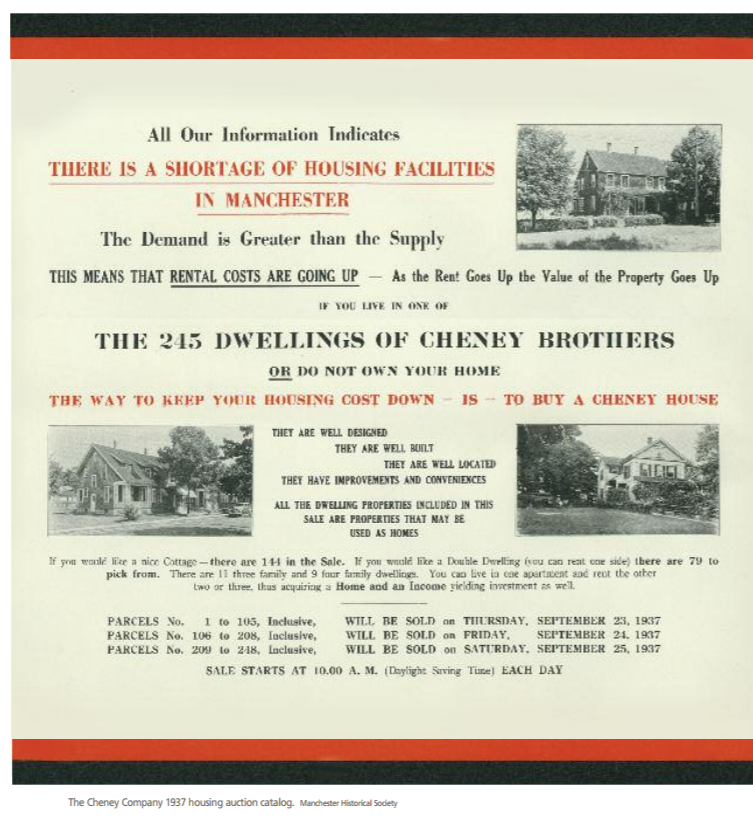

1937 was a bleak year. What could be done to attract buyers during a time when evictions and foreclosures were common and every newsreel showed farms across the country being seized by the banks? No expense wasspared in printing the sales materialsforthe auction. A catalog and poster enlist a “hard sell” approach common to real estate developers of the time to entice prospective buyers to attend the auction. Phrases such as “Demand is Greater than the Supply,” “Rental Costs Are Going Up,” “Every American Citizen Would Like to Own His Home,” and “Most Extraordinary Sale of Its Kind Ever to Be Held in the State of Connecticut” dominate the sales materials. Black-andwhite photos show tidy, attractive, nicely landscaped properties, each of which is described in three or four lines, and subdivision plat maps show each lot.

A sales office was opened at the corner of Pine and Pleasant streets, nearthe current home of the Manchester History Center. Prospective buyers were urged to stop by the office, pick up the catalog, and inspect the homes for sale. The sale included 144 single-family cottages, 79 two-family, 11 three-family, and 9 four-family homes—some only 15 years old. Also included were an inn (used by the company as a boarding house), a commercial property, and five multiple-car garages (including a six-car garage that still exists). Almost every home had electricity, gas, set tubs for laundry, a bathroom, and hot-air heat— conveniences not typically available to many working-class people. Site maps show homes set back from the street with large front and back yards.

The auction was organized as a three-day sale running September 23 to 25, 1937. Nearly 200 properties were sold on the first and second days, according to coverage in the Manchester Evening Herald, and 50 properties on the third day. The auctioneer moved down the block and stood in front of each home to be sold. On the first day, a gallery of at least 1,000 people followed the sale.

The Herald reported that in almost every case in which the current residents were known to be bidding on the property, competitive bidding ceased, and the current occupants prevailed as the high bidders. Every day the paper printed a list of addresses, the present occupant, the assessed value, the auction price, and the purchaser. During the first two days of the sale, properties were physically close together and the average auction time per property was about five minutes.

Two policemen guarded the auction-house clerk accepting the required 10-percent cash deposits. The Herald described nervous wives, their husbands at work, left to bid on the homes they rented or hoped to live in. Relatives tried to bid on double-family houses already occupied by family members. Sons and daughters tried to buy the houses that their parents had lived in for decades.

Ed Swain, now 84 years old, was nine when the auction took place. He attended school near where homes were auctioned on day two of the sale. “I was coming home from school and could see the crowd on a lawn. Cheney employees with their black lunch pails, coming home from the 7-3 shift, joined the crowd. Renters stood outside their homes,” he noted in an interview with the author on November 18, 2012. Nate Agostinelli, also a schoolboy at the time, wastold by kids on his way home that his father had bought a Cheney house. He later reported thinking, “No way, my dad couldn’t have bought a house, but sure enough, he borrowed $100 for the deposit.” Already living in a Cheney rental house at 358 Hartford Road, Albert Agostinelli had bought 72 West Street.

Amid newspaper photos of Mussolini and Hitler and articles about Japanese militarism, on September 27 the Herald reported that at the conclusion of the third day, 248 parcels had been sold for a total of $831,725. Proceeds from the sale represented 77 percent of the $1,081,000 the Reconstruction Finance Corporation loaned to Cheney Brothers in 1936, leaving less than $250,000 to be amortized during five and a half years from company profits. The 1937 occupants of at least 61 of the 245 residences purchased their homes. Manchester gasoline station owner Matthew M. Moriarty bought at least 33 properties. The newspaper estimated that about 90 families whose rental houses were sold would have to move within six weeks.

Amid newspaper photos of Mussolini and Hitler and articles about Japanese militarism, on September 27 the Herald reported that at the conclusion of the third day, 248 parcels had been sold for a total of $831,725. Proceeds from the sale represented 77 percent of the $1,081,000 the Reconstruction Finance Corporation loaned to Cheney Brothers in 1936, leaving less than $250,000 to be amortized during five and a half years from company profits. The 1937 occupants of at least 61 of the 245 residences purchased their homes. Manchester gasoline station owner Matthew M. Moriarty bought at least 33 properties. The newspaper estimated that about 90 families whose rental houses were sold would have to move within six weeks.

The Aftermath

In the years between the auction and the start of World War II, Cheney Brothers rebounded. Stiff budget cuts, investment in more efficient buildings and machinery, reductions in management personnel, and divestment of all unnecessary real estate helped keep the firm in business until the boom years of wartime production between 1941 and 1945. By 1954, though, the Cheney family sold the company, and over time, production in Manchester ceased.

A review of each of the approximately 248 buildings that were sold in 1937 reveals that only 19 were demolished between 1937 and 2012. The majority of these former mill-worker homes still provide roofs over the heads of Manchester families.

Mary Donohue is an architectural historian and assistant publisher of Connecticut Explored.

Read more Historic Preservation stories on our TOPICS page.