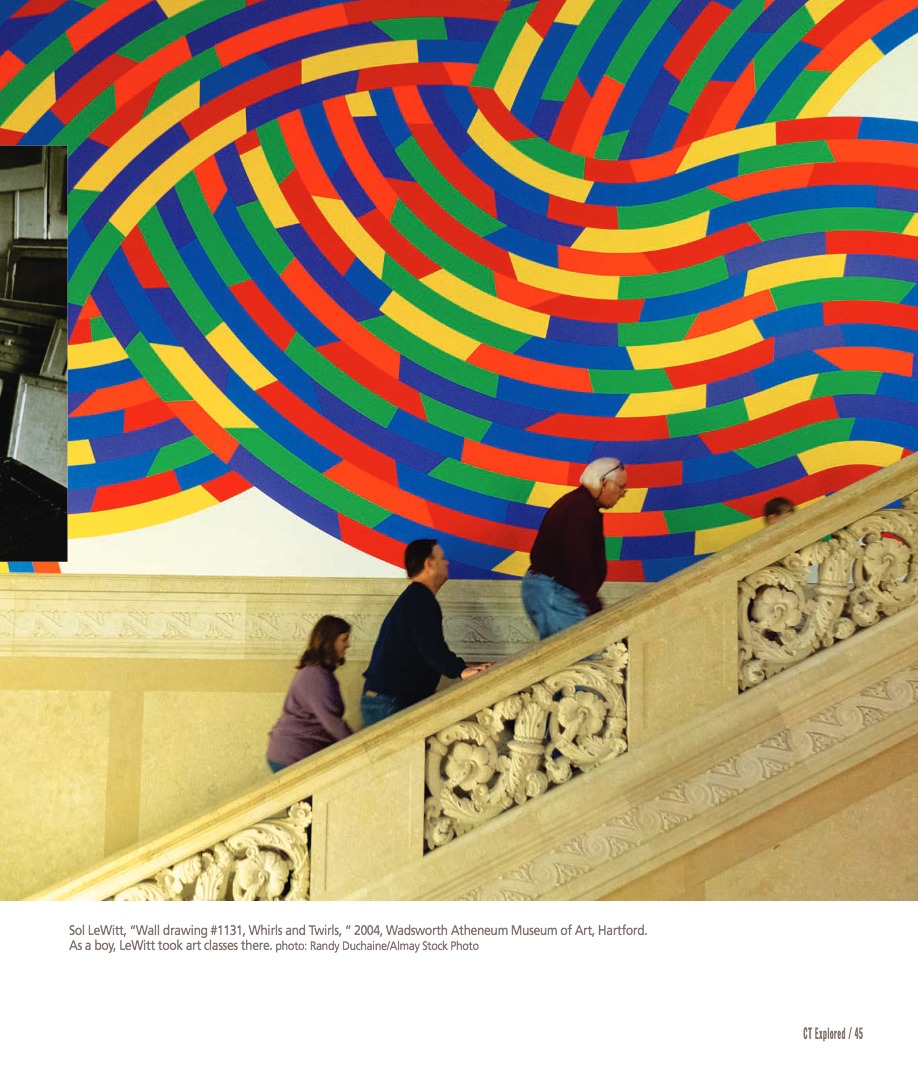

Sol LeWitt working on a wall drawing for his retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art, 1978. photo: Jack Mitchell/Getty Images

By Lary Bloom

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Fall 2019

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

This story is adapted from Sol LeWitt: A Life of Ideas by Lary Bloom, published in 2019 by Wesleyan University Press.

In May 1935, a six-year-old boy in New Britain used red and black pencils to draw a Mother’s Day card that featured, unsurprisingly, the image of a heart. When he finished his work, he gave the card to the woman who read Russian novels to him in the original language, cooked him borscht with potatoes and onions, and provided other homemade comforts in a period when, much too early in life, the child learned the meaning of bereavement. The Mother’s Day drawing, then, is both Sol LeWitt’s oldest surviving artwork and a symbol of the enduring bond between a mother and son.

That rendering of a heart, however, provides little evidence that its artist was a prodigy who one day would create a new definition of art and be celebrated worldwide for his bursts of creativity and innovative thinking. The heart is a little unusual, yes—instead of a wide and ebullient organ in the style of most childhood versions, it is narrow and deep, as if stretched from top to bottom. On the back of the card is this handwritten message: “ROSES ARE RED / VIOLETS ARE BLUE / YOU ARE THE BEST MOTHER / I EVER KNEW.”

Many decades later, after the adult Sol LeWitt was identified as a pioneer in two of art’s many “isms,” The New Yorker critic Peter Schjeldahl wrote, “The Minimalists scared me to death. Except for Sol LeWitt, who must have been dropped on his head as a kid. He’s the sweetest, most decent, most intelligent man in the world, and he’s a minimalist. How does that work?”

Dropped on his head as a kid? In a way, yes.

Solomon LeWitt, called “Solly” by his immediate family, was the only child of two refugees who emigrated from Russia but didn’t meet until they were living in the United States. Like all new arrivals from a different culture who spoke a different language, they had much to overcome. Each, though, set an example for their child about the need for independent thinking, taking personal and professional risks, and performing tikkun olam (Hebrew for “repair of the world”).

One piece of memorabilia from those days is a formal black-and-white photograph of a man dressed in a tailored woolen suit and waistcoat. It shows that Dr. Abraham LeWitt had angular cheekbones, an imposing forehead, a well-groomed mustache, and lips that were slightly downturned but that indicated a bemused demeanor.

At the time the photo was taken, circa 1930, LeWitt, his wife, Sophie, and their son lived at 3333 Main Street in Hartford. Like many of the single-family houses in Hartford’s North End, the LeWitt home was spacious—occupying 2,818 square feet and containing four bedrooms and two baths—reflecting Abraham’s standing as a surgeon and one of the founders of Mount Sinai Hospital. The hospital was then a new institution, where LeWitt served as medical director and specialized in disorders of the eyes, nose, and throat and also practiced surgery and invented several medical devices including clamps used in eye surgery and a girdle harness that helped intestines heal after abdominal surgery.

Abraham LeWitt’s route to this position had taken him from Hebron, when Palestine was part of the Ottoman Empire, to Russia, where he was one of the few Jews accepted into a school for mining engineers, and finally, in 1890, to New York City where he had family, and finally to New Britain to work at Russell & Erwin Manufacturing Co. But he had plans to become a physician and enrolled in the first class at the new Cornell University Medical College in Harlem.

Sol LeWitt’s mother Sophia Appell served as a nurse in World War I, July 15, 1918. The Hartford Courant

Sofia Appell was born in 1890 in Rostov-on-Don, in western Russia. Sophie, as she was known, was one of the seven children of Solomon and Elizabeth Appell. After the 1881 assassination of Tsar Alexander II, for which many Russians blamed the Jews, pogroms proliferated in cities and villages across Russia. In 1892 Solomon parted from his wife and children to see if he could find a place in America for them. That place turned out to be Colchester, Connecticut due to the efforts of Baron Maurice de Hirsch, a Jewish German banker. De Hirsch devoted some of his enormous fortune to helping Eastern European Jews emigrate to the U.S. and become farmers in New Jersey, New York, and Connecticut (See “Hebrew Tillers of the Soil,” Spring 2006).

By the turn of the century, the farm Solomon had bought, with de Hirsch’s help, had become a working concern, and shortly thereafter he sent for his family. Solomon’s family escaped just in time. In 1905 nearly 150 citizens of Rostov-on-Don were slaughtered in a pogrom. Sophie was then 16 years old, traveling with her brothers Sam, Moses, and Aaron aboard the Graf Waldersee. In Colchester she worked on the farm, but she also studied nursing.

A little more than a decade later Sophie was back in Europe—France, specifically—serving as a nurse during World War I. Three of her brothers, Sam, Harry, and Louis, served as soldiers toward the end of the war. A story in The Hartford Daily Courant (December 22, 1918) offers the following description of the only woman in the contingent:

Sophie Appell has done valiant service. After being called to service, she was temporarily on duty at Cape May, New Jersey, General Hospital #11 and was sent from there to France. Her letters tell of the wonderful morale of the American soldiers. She expressed pride in New Britain boys with whom she came in contact. A recent letter tells of having met David Rosenberg, Fred Ward, John Storey, Edward Hayes, Joseph Farr, and John Kerin, all well-known young men of the city. That Miss Appell was popular with her associates at Camp May is evidenced by the fact that in recognition of her service overseas, they named one of their rooms in the quarters at General Hospital #11 in her honor.

A year after her return, while working as a nurse in Hartford, she met a confirmed bachelor, Abraham LeWitt, 19 years her senior, who had treated her father. In 1920 LeWitt proposed to her. The two were married on January 16, 1922, at the home of Rabbi Abraham Nowack. Their only son was born in 1928.

In addition to his career as a doctor, Abraham took up writing, apparently as an avocation. In a 1933 essay he foresaw a time when the automobile and incompetent or inebriated drivers would be at the heart of a great number of deaths. The essay is exceptional for the amount of research he had done to bolster his argument.

LeWitt invested in real estate without much success—which may have led to his son Sol’s later expressing a reluctance to own property. Abraham’s investments were largely in properties in Hartford’s North End. Though these provided the level of income that allowed him and Sophie to travel and enjoy other luxuries, they also appear to have contributed to his eventually fatal medical condition. In the depths of the Depression, he was sued by his bank, Society for Savings, and even by his brother, for failure to pay what was owed them. On August 11, 1934, Abraham LeWitt collapsed at his home and died of a heart attack. Sol was a month shy of his sixth birthday.

In the following months, Sophie tried to avoid financial ruin. The only way she could manage was to try to collect rent herself: “She had to go door to door begging people to pay, and hated it,” according to Carol LeWitt, Sol’s widow. Eventually, Sophie realized that she would not be able to remain in her home.

When young Solly made his 1935 Mother’s Day card, he and his mother were living in a small apartment owned by Sophie’s sister, Luba Appell, in nearby New Britain. She had taken them in, but she did not have substantial means, either. Luba, who had lived alone, owned a small grocery store on the first floor of an apartment building, but she performed acts of charity, extending credit to those who in the midst of the Great Depression couldn’t pay their bills.

When young Solly made his 1935 Mother’s Day card, he and his mother were living in a small apartment owned by Sophie’s sister, Luba Appell, in nearby New Britain. She had taken them in, but she did not have substantial means, either. Luba, who had lived alone, owned a small grocery store on the first floor of an apartment building, but she performed acts of charity, extending credit to those who in the midst of the Great Depression couldn’t pay their bills.

The view from Aunt Luba’s kitchen table in the spring of 1935 resembled New York as portrayed by painters in the Ashcan school. New Britain was a city of soot, but it had jobs. During the Great Depression the number of workers in New Britain fell by a third, but the city’s factories still employed 11,000 men making hand tools, ball bearings, refrigerators, pots, machine parts, razor strops, coffin trimmings, and other items that had turned the city into an international destination for blue-collar workers, notes Patrick Thibodeau in New Britain, City of Invention (Windsor Publishing, 1989).

Downtown the sidewalks were crowded with people on their way to buy pirogues, sausages, or dark European bread, visit clothing shops, or go to the Polish-language movie theater on Broad Street. They might visit the jewelry and optician shop owned by the LeWitts—that is, members of Abraham’s extended family, who owned a variety of enterprises in the city and lived in much nicer housing than Luba’s.

Sophie and Solly’s circumstances improved, if only modestly, when Sophie found work as a school nurse in 1936 and they moved to a second-floor apartment of their own, at 51 Cedar Street, off West Main Street. The artist would recall in a 1974 interview for the Archives of American Art Oral History Program at the Smithsonian, “I . . . remember living in a part of town that really wasn’t a very good part of town. It wasn’t so bad really. But I remember that people were out of work.”

The Cedar Street apartment building in New Britain where artist Sol LeWitt lived during most of his youth. photo: Lary Bloom

The Cedar Street location had at least one advantage: It was within easy walking distance of the library and the New Britain Museum of American Art. Few people could afford automobiles in the 1930s. Sophie would never learn to drive, and neither would her son (though certain people in rural Italy could later testify that he took the wheel of a car at least once). The art museum was a community gathering spot, as in those days admission was free—primarily as a result of the generosity of the hosiery manufacturer John Butler Talcott and the philanthropist Grace Judd Landers.

When a boy loses a father at a tender age, there is often speculation about the effect of the loss and the legacy of the father. The earliest evidence, from the recollections of childhood friends and school records, shows that the young Solly seemed withdrawn. Miss Brown, a teacher at Lincoln Elementary School in New Britain, wrote: “Solomon is a sober little fellow. He needs to smile and enjoy other boys and girls. He does very good work but acts too old for his age.”

As years passed, however, Sol showed signs of an emerging sense of humor. Walter Friedenberg, Solly’s boyhood friend and classmate at Central Junior High, remembers: “He was not loquacious, and his diction was slurring. But he was alert, companionable, and witty. He had a giggle. That little giggle.” Friedenberg remembered the games their group played. There was football at Walnut Hill Park and baseball wherever the kids could play it. In those games, Solly LeWitt fit in nicely.

No doubt, however, he was different from other boys. One way was in his choice of which professional baseball team to follow. New Britain is halfway between New York City and Boston, and the loyalties of the Hardware City’s residents always have been split between the Yankees and the Red Sox. Solly, however, supported the Cleveland Indians, whose home games were played hundreds of miles away. This wasn’t because of the physical and historical connection between Connecticut and Northeastern Ohio. Solly likely wasn’t even aware at the time that that part of Ohio had once belonged to the Constitution State—it was its Western Reserve, where Cleveland sits. He told his friends simply that a person should think for himself. And when he thought for himself, he liked “the Tribe.” He never saw the Indians play in person, and this was long before televised games. So he followed them in radio broadcasts, box scores, and brief game accounts in the New Britain Herald. This loyalty earned Solly a healthy dose of abuse, something he laughed about later—but he remained an Indians fan until his death. (As I was his friend in his later years, and like him a life-long fan of the same team, we consoled each other when the Indians lost the seventh game of the 1997 World Series in heartbreaking fashion.)

Entering his teens, Solly became a member of the Boy Scouts and went several days a week to Hebrew School at Temple B’Nai Yisrael, the conservative congregation of New Britain. The city had two synagogues at the time, the other orthodox. In early October 1940 Solly was called to the Torah for the first time as a bar mitzvah. Among other duties, he delivered a short speech that Saturday morning. His message indicates the views of a boy who understood what his mother had done for him. Sol’s speech read, in part, “Spare, I pray Thee, my dear mother for many a year. Bless her for the tender attention and selfless care she has given me to this day. May it be Thy will that she live many years to witness the results of her toil so that she may see that she has not labored in vain.” As his cousin Celeste LeWitt would say decades later, “Sophie’s whole life centered on her one child, and she never walked past him without giving him a hug.”Indeed, Sophia LeWitt lived until 1978, the year that her son had his first retrospective, an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City that secured his place as one of the most influential American artists of the 20th century.

Lary Bloom is a writer, was founding editor Northeast magazine, co-founder of the Sunken Garden Poetry Festival and Art For All, and author of Lary Bloom’s Connecticut Notebook (Globe Pequot Press, 2005) and other books. He last wrote “West of Eden: Ohio Land Speculation Benefits Connecticut Public Schools,” Summer 2007.