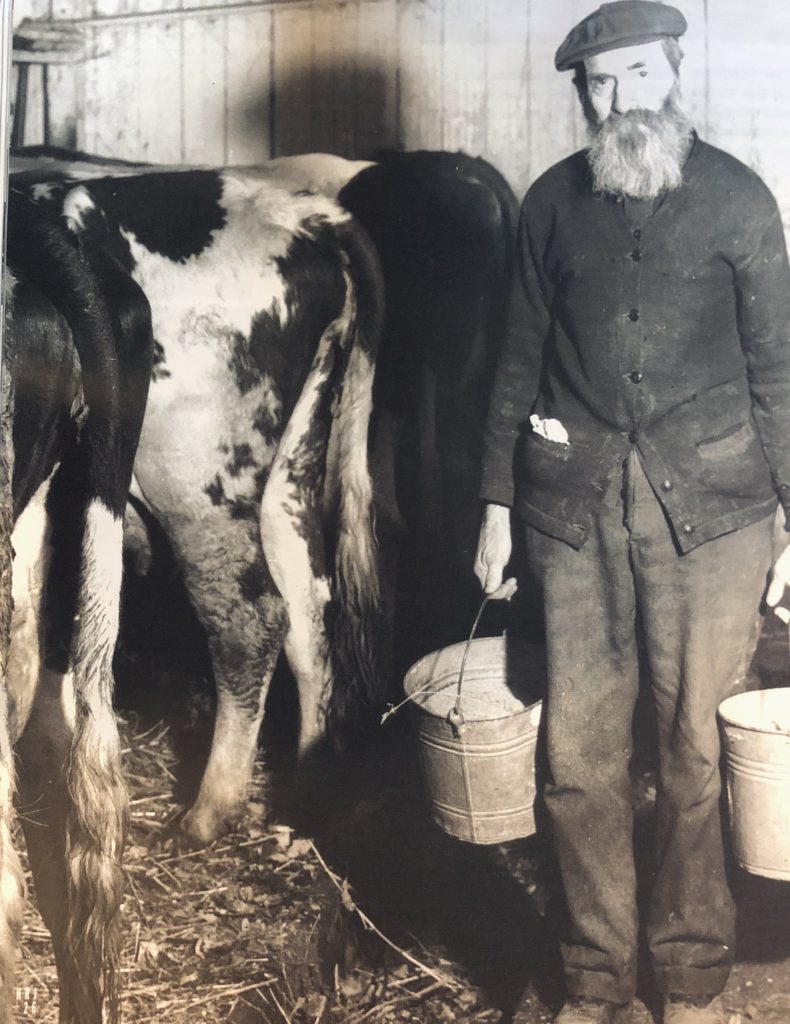

Abraham Lapping in his barn, Colchester, 1940. The Lappings took in guests. photo: Jack Delano, Library of Congress

by Mary Donohue and Kenneth Libo, M.D.

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. SPRING 2006

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

The legacy of Jewish farming in Connecticut is an important part of our state’s agricultural history. Much of it was documented in the 1998 report Back to the Land: Jewish Farms and Resorts in Connecticut 1890-1945 by Janice P. Cunningham and David F. Ransom, published by the Commission on Culture & Tourism (CCT) and the Jewish Historical Society of Greater Hartford (JHSGH). This year, with funding from the Connecticut Humanities Council, Dr. Kenneth Libo will publish an updated history in JHSGH’s journal Connecticut Jewish History. Libo’s work takes the history of Jewish farming up to the present, including the story of new Jewish immigrants arriving after World War II and the development of Jewish-owned agri-businesses. This story is drawn from both Back to the Land and Dr. Libo’s research.

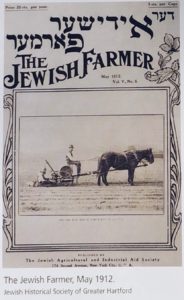

Connecticut’s Jewish farmers have been thought of as a novelty since they began to arrive in the 1890s. Who ever heard of Jewish farmers? Jews typically aren’t associated with farming-and certainly not with successful farming. Forbidden from owning land in Russia, Jews still came to American with some agriculture skills gained through cattle dealing, tenant farming, or raising cows, goats, or chickens. But in Connecticut, Jewish farmers pioneered the adoption of foodstuffs-such as eggs, milk, and broilers-that could be raised on worn-out, rocky New England soil. Large-scale use of scientifically designed chicken coops, the Jewish farm agent, the Jewish farm newspaper, and the Jewish farmers’ cooperative all became highly visible and successful aspects of Jewish farming in Connecticut. The first farmers’ credit union in the United States was formed by the Jewish Agricultural and Industrial Aid Society in 1911 in Fairfield, Connecticut, creating a model used across the country.

Why Connecticut ?

Persecuted for two centuries under Russian rule, Eastern European Jews began emigrating to the United States in droves in the 1890s. Alarmed by the plight of refugees pouring into Western Europe, wealthier Western European Jews undertook relief efforts.

An immigrant generally has some resources-money to buy transportation tickets and food, family connections in the new country, and an established ethnic community to join. A refugee has nothing-no money, no connections, no one looking out for him, and, most significantly, absolutely nothing and nowhere to return to. Eastern European Jews were typically refugees.

The Baron Maurice de Hirsch (1831-1896), a wealthy German Jew and lifelong philanthropist, founded the Baron de Hirsch Fund in Germany in 1891. The first specifically agricultural efforts of the Fund were directed toward revitalizing foundering Jewish farm colonies in New Jersey. The Fund purchased a 5,300-acre tract in Woodbine; with help from the Fund, the site became America’s first long-term Jewish agro-industrial community. In 1894, the Baron de Hirsch Agricultural College was established in nearby Vineland, New Jersey. Future Connecticut farmers numbered among its graduates.

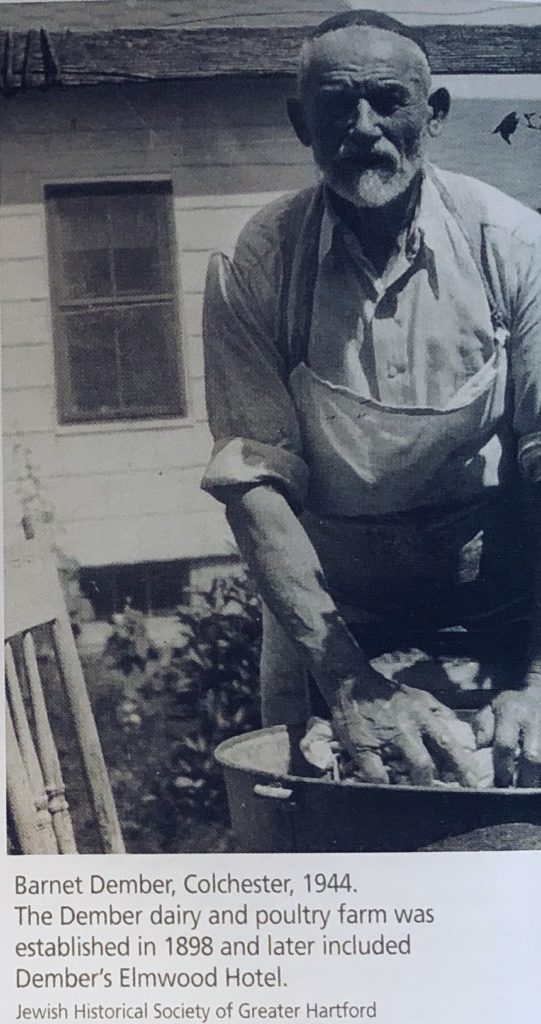

Barnet Dember, Colchester, 1944. The Dember dairy and poultry farm, established 1898, later included Dember’s Elmwood Hotel. Jewish Historical Society of Greater Hartford

In the United States, the Fund, managed by the Jewish Agricultural Society (JAS), helped Jews move out of the big cities, notably New York. The Jewish “Back to the Land” movement stressed the redemptive nature of farm life. German Jews who had arrived in America since the 1840s and had had some measure of success worried about the high numbers of Eastern European Jews living in crowded, filthy conditions in a tiny area on the Lower East Side of New York City. They also worried that these impoverished Jews, with their foreign dress, language, diet, and customs, would arouse virulent anti-Semitism. These sentiments drove the charitable impulse to move Jews out of the city to America’s small towns and countryside. Jews were sent to become farmers in rural Connecticut, New York, and New Jersey, as well as to far-flung places with picturesque names such as Bad Axe, Michigan.

In Connecticut, the JAS began focusing on two areas in which to establish independent Jewish-owned and run farms, one encompassing Colchester, Lebanon, and Chesterfield, and the other Rockville, Vernon, Ellington, and Somers. They located abandoned or up-for-sale farms in these areas whose Yankee owners and families had moved to the city as a result of industrialization. The JAS then provided prospective Jewish farmers with help, sometimes with loans, though more often with advice.

After 1908, farm agents of the JAS provided mortgages to Jewish immigrants, helping them locate and purchase farms appropriate in size and type to the individual farmer’s needs and skills. Almost all of the refugees had to adapt to a new culture, climate, and occupation. The farm agents often helped them to obtain farms that featured not only a house and barns but also household furnishings and farming equipment. Farm wagons, cars, and trucks are often cited in the deeds. “When some of the old Yankee farms were auctioned off and the Jews bought them, they did not pay a whole lot,” recalled Zeke Leverant of Colchester. “I remember back in the ’20s a family bought 25 acres, 7 cows, and 20 chickens for $3,800.”

In granting mortgages, the JAS often wrote into the deeds stern stipulations the farmer was required to follow, including the following directives:

1. Keep the property insured against fire.

2. Occupy the premises; reside there.

3. Commit no waste thereon.

4. Engage in no change in ownership.

5. Keep the buildings in sanitary condition.

6. Cultivate said farm.

7. Pay the taxes.[2]

In exchange, the JAS agreed to take a second or third position among creditors. One deed in Columbia gave a farmer $1,200 for 150 acres of land with buildings in Columbia and Hebron that already was encumbered with a first mortgage of $2,100 and a lien of $1,900. The schedule of payments of principal called for the amount of $150 annually from 1924 to 1927; $200 annually thereafter, and interest at 5 percent.

Initially, beginning in the 1890s, Jewish farmers continued the type of subsistence farming practiced in the state in which the farmer grew crops principally for his family’s consumption and sold any extra. But in the 1920s, as the consumer demand for eggs, milk, and poultry grew, specialization became much more profitable than subsistence farming.

In 1911, the Agricultural Experiment Station in New Haven discovered Vitamin A in whole milk. Mothers were encouraged to include cow’s milk in their children’s diets. The University of Connecticut at Storrs displayed scientifically designed chicken coops in 1918. These and other modern, scientific farming methods were continually published in The Jewish Farmer. Jewish farmers were very progressive and quick to adopt these new practices. Jews did particularly well in the poultry industry, not only as farmers but also as feed suppliers and chicken dealers, carting chickens to wholesalers and retailers who as often as not were Jewish.

Connecticut Jewish farmers had no ready-made Jewish farming community to step into. Rather, they were on their own in constructing a Jewish life for themselves and their families in an overwhelmingly gentile environment. Even so, they lived close enough to towns like Norwich, New London, Willimantic, and Colchester, where they could subsidize their farms income by working as tailors, shoemakers, or butchers, trades brought over from the Old Country.

Yankee Reaction

In the decade that followed World War I, more than 1,000 Jewish farm families settled in Connecticut. Nativism and opposition to immigration reached its zenith in 1924 when for the first time the United States Congress imposed immigration quotas for Eastern European countries. In a series of articles from 1925 preserved in undated newspaper clippings in the scrapbooks of the Connecticut Department of Agriculture, reporter Isabel Foster wrote about state residents’growing concern about the number of farms being run by foreign-born (including Jewish, Italian, Scandinavian, Polish, and French-Canadian) proprietors. Foster wrote:

ALIEN INVASION OF CONNECTICUT FARMS. Every Third Farm in Connecticut Is Now in the Hands of a Man of Foreign Birth, Almost Rivaling Minnesota and North Dakota

What does this mean for the future? A new poverty-stricken Poland, Galicia, Ireland, Russia in the pleasant valleys of this state? The Yankee farmer driven to the stones and snows of the North or like the Indian before him, obliterated? Or can it mean a new life for all, a renaissance of strong pioneering spirit, of vigorous ambition and great accomplishment? [3]

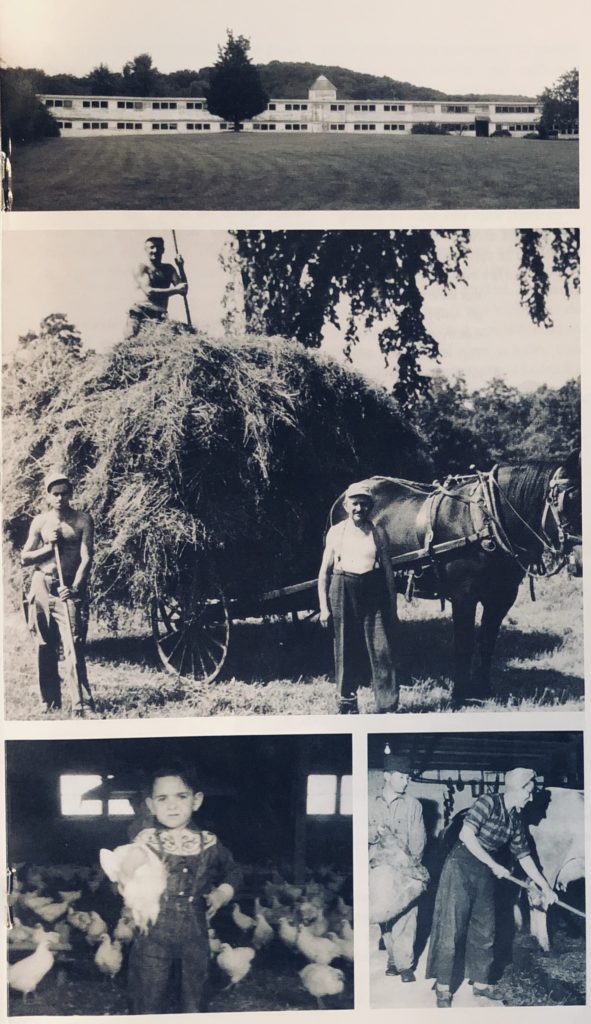

top: Joymax Farm, East Haddam. photo: David F. Ransom, Commisson on Culture & Tourism. Middle: Lebanon Farm, Leon Simon on hay wagon, Sam Schwartz and father, below. Jewish Historical Society of Greater Hartford. Bottom left: Boy on Sol Sadek’s farm, Lisbon. Sadek and his wife emigrated from Poland in 1946 aided by cousins in nearby Canterbury. Jewish Historical Society of Greater Hartford. Bottom right: Zelda and Morgan Himmelstein. Lebanon Historical Society

Raising A Crop of Tourists

Farming was not all that took place on Jewish-run farms. Providing lodging for Jewish summer guests became a common way for Jewish farmers to make ends meet. Farm families found themselves catering to fellow Jews drawn by the promise of fresh food prepared in kosher kitchens and a respite from smoldering summers in New York City tenements. The host farmers could be counted on to uphold Jewish dietary laws: The services of schochets (ritual slaughterers) were obtained for preparing fowl, and by the 1920s, kosher butcher shops could be found in small country communities such as Colchester. One former resident recalled, “There was a kosher butcher and I still remember where it was, a little house right across the street from the Colchester Laundry. The schochets was there to take care of the chickens. My father would bring them on the same bus my sister and I would take to school.” [4]

Without air conditioning, summer in New York was stifling. Reporter Isabel Foster described the summer influx of Jews to Colchester:

In the summer the population jumps to 10,000 because of the summer visitors from the tenements of New York.Those who do not like to see a dignified and quiet old town turned into a resort for city workers should soften their hearts by spending a hot week in August sleeping in a court room on the upper East Side of New York. It will then be a matter of rejoicing to them that these poor people can get away to the green country for a few weeks. They will look with delight into the sheds labeled Banquet Hall where a long table and two benches serve as the only furniture and at the hammocks hung in the run-down apple orchard-even at the noisy groups who gather in the town’s little stores.[5]

A koch-a-lein, literally “cook for yourself,” arrangement was typical. This meant that the guests cooked their own food in the farm kitchen. The farmer would profit not only by receiving the weekly rent, but also by selling fresh ingredients to the guests. The farm family would move out of their bedrooms and into the barn. Farm boardinghouses that provided meals as well as rooms were less common, but Pincus Schwaitzberg’s advertisement for the Elem Farm House in Mansfield calls the farm a “first class summer place.[with an]elegant summer garden, fresh butter, milk, and eggs every day, and fine spring water.”[6] Unlike today’s famous “fat farms,” spas that promise guests will lose weight during their stay, Connecticut’s early 20 th -century Jewish farm hosts prided themselves on putting weight on their city guests.

Visitors came by train from New York’s Grand Central Station and were picked up by farm wagons. Saul Mindel described his parents’ accommodations for boarders: “There were several bungalows. One was originally an icehouse. One was originally a chicken coop.the city of Norwich disposed of their trolley cars and we were able to obtain one and turn it into a bungalow.”[7] Rates reflected the working-class background of the guests. Sol Kiotic remembered: “My mother charged eighteen dollars a week for room and board. That was very reasonable. For the roomer it was eighty dollars for the season.”

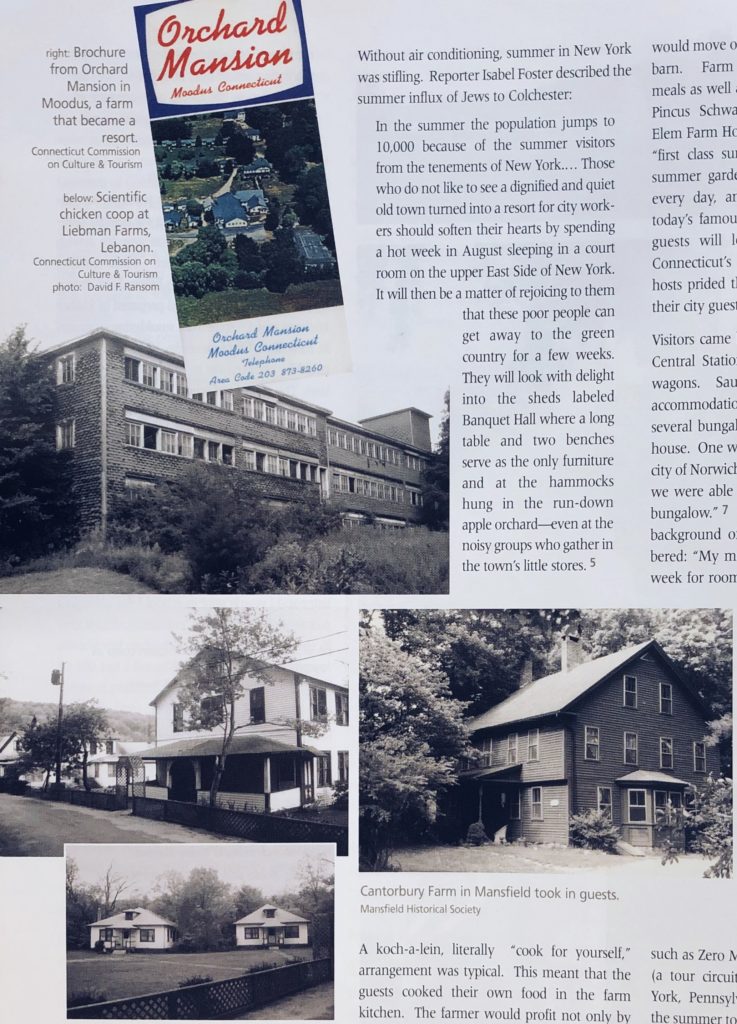

top: Orchard Mansion brochure. top middle: Scientific chicken coop at Liebman Farms, Lebanon. photo: David F. Ransom. middle left and right: Cantorbury Farm, Mansfield, took in guests. Mansfield Historical Society. Bottom: Cottages at Levy’s Grand View, Colchester, 1996. photo: David F. Ransom. All images Commission on Culture & Tourism unless otherwise noted.

From guests staying in the farmhouse, some places eventually developed into resorts. Resort buildings included boarding houses, cottages, hotels, bungalows, and camps, which often offered waterfront recreation, dining halls, and nightly entertainment. More than 30 small resorts have been inventoried by the Commission on Culture & Tourism’s survey program. Famous Jewish entertainers such as Zero Mostel traveled the “Borscht Belt” (a tour circuit that included venues in New York, Pennsylvania, and Connecticut ) during the summer to perform at these family-oriented resorts. Many of these resorts survive and are now youth camps or religious retreat houses.

Keeping the Faith

Evidence of the Jewish faith of these farm families emerged in the building of places of worship in these rural communities, some of which are still standing. Country synagogues are found in Hebron, Lebanon, Lisbon, and Colombia. Two more, one in Chesterfield (since demolished) and Ellington, received construction loans from the Baron de Hirsch Fund. One has been identified in Newtown. Summer shuls (“shul” being the Yiddish term for “synagogue”) were also constructed in Danbury, Milford, New London, and Old Lyme. Ken Libo, raised on a poultry farm in Lisbon, recalled

What kept many Jewish farm families going, even in the toughest of times, was an unshakable determination to survive as a Jewish family-to take the necessary steps and make the necessary sacrifices to stay Jewish. There was never any question.Ours was a thoroughly Jewish household in which the calendar revolved around Rosh Hashonah, Hanukkah, and Pesach [Passover]. As a child living close to the soil I felt very close to the Old Testament patriarchs.[8]

Making a Success of It

Food was essential to the Jewish identity. “My mother in the early days milked cows by hand. And you have to remember she cooked everything we ate. Nothing bought was ready made. She would make challah. She would make bobka. She canned vegetables. She made farmer’s cheese [that hung]on a line outside. Blintzes. She worked very hard,” relates eastern Connecticut Jewish farmer Harvey Polinsky. [9]

Not surprisingly though, many Jewish farmers did not make it. Economic panic, depression, or collapse of farm prices occurred with regularity every decade and a half. As early as the 1860s, many Yankee farmers had given up farming for mill work or moved west for more productive land. What is surprising is that so many of Connecticut’s Jewish farmers did make it.

In a newspaper article with the headline “JEWISH FARMERS PROSPER IN CONNECTICUT, Living Down Their Reputation as Mere Middlemen Who Do No Labor, They Have Shown That They Can Till the Soil and Make It Pay” (circa 1925), reporter Isabel Foster credited the JAS and its sponsored farmers for their commercial success and for literally creating something out of nothing. [10]

What are the factors that contributed to the success of those Jewish farmers who thrived in Connecticut ? In some cases, it was just good luck: a good location with close proximity to urban areas (including Hartford, New Haven, New London, Norwich, and Willimantic) that provided demand for fresh eggs, milk, meat, and produce and afforded access to trolley, truck, bus, and train for transportation of foodstuffs to market. Important nutritional discoveries like milk’s Vitamin A and the development of sanitary, scientifically designed farm buildings benefited all farmers. The help of the Connecticut Agricultural College at Storrs where the first Jewish student was enrolled in 1898, and the State Department of Agriculture and their farm agents ended the farmers’ isolation and kept them informed. But Jewish farmers also had a powerful ally: the JAS with its own farm agents, publications, and, perhaps most important, money to lend, often as a second or third mortgage. These essentials all supported the individual farmer family’s own ingenuity and business savvy in turning a worn-out Yankee farm into a flourishing resort or, after World War II, an agri-business.

The full story of the impact of Jewish farmers in Connecticut is just coming to light. The lives of the earliest arrivals in the 1890s and the post-World War II immigrants both need extensive research before their unique role in the state’s agricultural history is fully revealed.

Explore!

“The Connecticut Catskills,” Summer 2018

“Faith Amidst the Fields: Connecticut’s Country Synagogues,” Winter 2010/2011

“Jews in Hartford: Making Their Presence Known,” Summer 2005

Footnotes

[1] John F. Carr, Guide to the United States for the Jewish Immigrant (The Connecticut Daughters of the American Revolution, 1912)

[2] Janice P. Cunningham and David F. Ransom, Back to the Land: Jewish Farms and Resorts, 1890 – 1945 (Connecticut Historical Commission, 1998)

[3] Isabel Foster, undated newspaper clippings, c. 1925, scrapbooks in Record Group 098, Department of Agriculture, 1866 – 1978, State Archives, Connecticut State Library

[4] Kenneth Libo, interview with Marion Jaffe Major, 2005.

[5] Foster.

[6] Cunningham and Ranson.

[7]Libo, Back to the Land: Connecticut Jewish Farm Families, 2005, unpublished manuscript, Jewish Historical Society of Greater Hartford

[8 – 10] Ibid.