By Jennifer LaRue (c) Connecticut Explored, Fall 2015

By Jennifer LaRue (c) Connecticut Explored, Fall 2015

In the late 19th century, even as great classical music was being composed in Europe and the United States and parlor music was popular in American homes, hearing music required being there in person. After all, the radio wasn’t invented until the late 1890s, and radio broadcasting didn’t begin until the 1920s. In a small city such as Hartford, band, and choral music concerts were more readily available than those featuring classical music.

In 1891, the year Thomas Edison received his patent for wireless telegraphy (a key step in the development of radio), six young women—Frances “Fanny” Hall Johnson, Elizabeth “Bessie” Davis, Sarah Goodwin, and sisters Mary “Molly” and Grace Plimpton—gathered on a springtime Saturday morning in Johnson’s Gillett-street home. All friends and neighbors from the tony Asylum Hill neighborhood (Goodwin was the daughter of Rev. Francis Goodwin, parks commissioner of Hartford and former rector of the neighborhood’s Trinity Episcopal Church), they wished to form a group within which they could explore and share their love of music. Johnson, a 28-year-old pianist and piano teacher who lived with her widowed mother and would write Musical Memories of Hartford (Finlay Brothers, 1931) a history of the city’s musical life, would become the club’s first president upon its formal founding, with constitution and bylaws, in 1893.

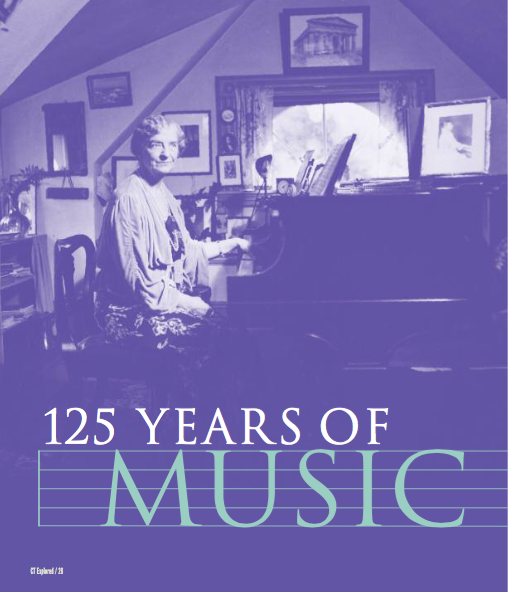

The Musical Club of Hartford celebrates its 125th anniversary this year. As a function of its mission and the personalities of its members, the club has from its founding focused on cultivating the Hartford area’s musical life through sharing time, talent, and treasure.

The late 1800s were a club-happy time in Hartford and in other American cities. Women had long formed temperance societies and other social reform associations. But women with leisure time and resources sought to pursue practice of the arts as well. The Saturday Morning Club, a young women’s literary group, was founded in 1876; the Hartford Decorative Art Society—a women-led art school that later formed the nucleus of the University of Hartford’s Hartford Art School—was founded the following year [See “An Art School Forged in the Gilded Age,” Summer 2003.]

Those were also lively musical times. As Johnson writes in Musical Memories, Hartford residents could hear classical music such as pianist Anton Rubinstein performing with Theodore Thomas’s New York-based orchestra at the Roberts Opera House in 1873; Aida was performed there in 1874 and Bizet’s Carmen in 1879. People could hear the local 200-voice Hosmer Hall Choral Union, founded in 1880. The Hartford School of Music was founded in 1890, and Hartford was soon to be home to the 36-member instrumental group that would become the Hartford Philharmonic Orchestra, founded in 1899. (Frances Johnson was the organization’s secretary.) In 1890, 75 music teachers advertised their services in Geer’s City Directory, and in 1902, 8 of the School of Music’s 10 instructors were women, according to Geer’s City Directory.

The amateur singers and pianists—most of them in their 20s—who founded The Musical Club wanted more than just to listen as passive audience members. They sought a forum wherein they could develop their musical skill by providing opportunities to perform for others, exchange constructive criticism, and undertake serious study of music, music theory, and the musical realm worldwide—and thus to enhance their own skills, knowledge, and appreciation. They also hoped to “give assistance to promising young artists,” as their by-laws stated, and “to aid musical projects.”

To that end, the first members of the club set out an ambitious agenda: The group would meet every Saturday afternoon at a member’s home, November through May; once a month an evening musicale would be held with refreshments such as coffee, sandwiches, and cake. Eight or nine members typically performed—a vocal performance followed by piano repertoire. On November 4, 1893, Alice Bulkeley played a challenging prelude by Bach after Molly Plimpton sang “Sunset” by Edvard Grieg. Initially works were performed on piano, organ, or voice, but string instruments soon entered the mix and performances were organized according to set themes. Most performances featured small ensembles, such as solos, duets, and trios. Once a month the program included the reading of a paper by one of the members or a lecture by an outside guest.

Viola Vanderbeek, on the 70th anniversary of her membership, provided a sense of what the early club was about. “I remember when, soon after we moved to Hartford in 1891, I was asked to join a group of girls, all studying music, who met to play and sing for each other in their respective homes. … It was the day of the ‘parlor musician.’ … The school girl phase passed, however, as more mature musicians and teachers came into the club.”

Viola Vanderbeek, on the 70th anniversary of her membership, provided a sense of what the early club was about. “I remember when, soon after we moved to Hartford in 1891, I was asked to join a group of girls, all studying music, who met to play and sing for each other in their respective homes. … It was the day of the ‘parlor musician.’ … The school girl phase passed, however, as more mature musicians and teachers came into the club.”

One of the “musical projects” that The Musical Club supported was the nascent Hartford Philharmonic Society, founded in 1899. Among the 20 violinists were 7 women; 1 of the 6 viola and 1 of the 3 cello players were women. Johnson recalled in Musical Memories of Hartford, “I can well remember the afternoon, the look of the small band of players, and can recall the music. They were practicing on Beethoven’s First Symphony. The thought of having an orchestra that belonged to our own city acted like a tonic. The next step was to have Mr. [Richard P.] Paine [conductor]give a lecture to the Musical Club about the instruments.” That lecture had to wait, however, for the arrival of the orchestra’s first bassoon—underwritten by prominent Hartford citizen Susan Warner (Asylum Hill resident and associate member of the Musical Club). When the event occurred, Paine brought members of the orchestra with him to play each instrument. “The new bassoon made a decided impression,” Johnson notes. Many Musical Club members were among the patrons of the Philharmonic Society’s first concert, in April 1900, at Parson’s Theatre.

The active membership was limited to women (until 1983, when men became eligible). Those wishing to join the club were put through a rigorous process of vetting. Candidates had to perform before the club and their nominations to be made and seconded, approved by two separate committees, and voted on by the entire membership, which judged them on their overall eligibility and their musical qualifications. An associate membership allowed others, including men, to listen in on certain public sessions. By 1900-1901, 79 men were associate members. As Vanderbeek noted, “the list sounded like the social register of the day.” Despite this rigorous and exclusive selection process, the membership rose to a peak of 525 members in 1930.

In planning the year’s schedule, the members aimed for a mix of familiar favorites and more challenging choices of music, with opportunities for delving deeper into well-known works and exposure to newer material or that outside the classical, mostly European, canon. The club met at the homes of members for two years before, Johnson notes, “We became rather dissatisfied with meeting in private homes and moved to our new quarters in the music room at Hosmer Hall on Broad Street where we had two pianos, access to the Musical Library and facilities better in every way to carry on the work of the Club.” The club’s meetings have since moved from time to time, including to a room at the Hartford School of Music and the Colonial Room at the Bushnell.

Over the years The Musical Club has brought many marquee names to Hartford, including, for its first concert, in 1898, pianist and composer Edward MacDowell (the American composer and pianist of the romantic period whose wife founded the MacDowell Colony in his memory and who was then at the height of his fame). Johnson called his playing “electric, rapid…. This first concert was a landmark in the Club’s history.” Pianist Ossip Gabrilowitsch and his wife Clara Clemens, a soprano and daughter of Samuel, performed a joint recital for the club in February 1915. And in 1937, the Musical Club joined with the Bushnell Memorial to bring a soon-to-be world-famous Marian Anderson to Hartford. In a 90th-anniversary history of the club, The Pursuit of Music, author Priscilla Rose reported:

The Bushnell Memorial management approached the Musical Club and suggested joint concerts by artists whom neither group could afford to sponsor alone. We agreed to that plan, and on May 6, 1937, Marian Anderson, contralto, fresh from her European triumphs, sang under these joint auspices. Because she was more or less unknown to local music lovers, the seat sale was almost a disaster. By noon we had decided to “paper the house.” This was done and a respectable audience greeted the great singer whose artistry was appreciated for its quality. The concert was a great musical success and shortly thereafter Miss Anderson’s New York debut placed her in the top rank of concert artists, far beyond local financial reach.

Maintaining sufficient funds to cover costs has often posed a challenge, as the club has juggled the desire to keep annual dues low (at first, the 18 active members paid just $2—only $53 in today’s dollars!) with the realities of waxing and waning membership numbers. Beginning in the 1930s, as middle class women began to enter the workplace, fewer found time to devote to such activities as participation in a club that makes substantial demands on its members. Today the membership remains fairly stable at 300 members.

Maintaining sufficient funds to cover costs has often posed a challenge, as the club has juggled the desire to keep annual dues low (at first, the 18 active members paid just $2—only $53 in today’s dollars!) with the realities of waxing and waning membership numbers. Beginning in the 1930s, as middle class women began to enter the workplace, fewer found time to devote to such activities as participation in a club that makes substantial demands on its members. Today the membership remains fairly stable at 300 members.

For its first 32 years, the club benefited from a benefactor. Merritt Alfred of the Hartford music store Gallup and Alfred helped fund the group’s activities and even went so far as to absorb any annual losses. A key event in the club’s development was its decision, in the 1921-1922 season, to become financially self-sufficient. That move proved successful, with membership dues supporting increasingly ambitious programs.

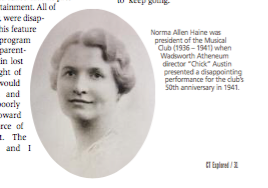

Of course, no organization lasts 125 years without hitting some rough patches. The club’s leadership pulled no punches in addressing one program that apparently went miserably awry. Norma Allen Haine, the only member to serve five terms as president, reported in her account of the 1941 50th-anniversary dinner:

The Entertainment Committee consulted Mr. A. Everett Austin, Curator of the Avery Memorial [of the Wadsworth Atheneum, of which Austin was in fact the director], and asked that he present an entertainment. All of you, I know, were disappointed in this feature of the program because apparently, Mr. Austin lost complete sight of what we would really like, and produced poorly a Noel Coward bedroom farce of little merit. The Committee and I can only apologize. …. When we celebrate our 100th Anniversary we will feel more confident that Musical Club talent is far superior to art society talent and we will insist on our members providing the entertainment, this lesson having been learned by bitter experience, the greatest of all teachers.

By the time of the club’s 100th anniversary, fences had long been mended. President Audrey Lindner reports in her summary of her tenure that, “In 1983 a happy agreement with the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford made it possible to begin a pattern of holding one program a year there, in conjunction with an art exhibit, on a Sunday afternoon. This accommodated our working members, performers and listeners alike, and the program was well received by the public.”

Two world wars and the Great Depression took their toll on the club. But the group persisted, taking the nation’s challenges as their own. As Rose reports, during World War I, “Some members of the Musical Club worked in factories on Capitol Avenue while their menfolk were at the Front. Attendance at meetings and concerts suffered somewhat. Many knitted as they listened, but Musical Club tried bravely to ‘keep going.’”

In her address to the group in May 1918 as the war raged in Europe, club President Lillian Bissell said, “It is only just to our better selves that we keep alive our interest and intimate association with music and let it do for us all that it is capable of doing in the otherwise material life which we are obliged to live at this particular time. The inestimable value of the quiet hour of music [the Club provides]in these days of constant strain should be treasured.”

World War II brought similar challenges to the membership, with many participants devoting time to war-related  volunteer activities or factory work. Still, with active membership having dipped below 300, the club rallied to raise funds to purchase, as part of a nationwide effort, music recordings and listening equipment for those serving abroad. Rose writes, “It was especially meaningful for submarine crews who were away from civilization for months at a time and who, for reasons of safety, could not use the radio.”

volunteer activities or factory work. Still, with active membership having dipped below 300, the club rallied to raise funds to purchase, as part of a nationwide effort, music recordings and listening equipment for those serving abroad. Rose writes, “It was especially meaningful for submarine crews who were away from civilization for months at a time and who, for reasons of safety, could not use the radio.”

Rose notes that the club continued over the years to enhance its support for young music students in the area, supporting the purchase of instruments for high-school students, paying for young musicians to attend music camps, and providing scholarships for promising young performers.

The Musical Club Today

The group has continued to update and modernize its operations. In 1983, the club opened its active membership to men. And in 1990, after years of pursuing this goal, the club was afforded federal tax-exempt status, which provided financial benefits that have helped keep the operation in the black. By 2000, facing a waning membership, the Club did away with the distinction between active and associate memberships; from then on, membership, as their annual yearbook states, is “open to all those who share a love of music, including performers, listeners and composers,” although those who wish to perform must audition. Today, approximately half of the 300 members are performing members. Members are also invited to help organize concerts and programs and serve on the scholarship committee.

Funds are raised annually to provide scholarships to high school and local music students. In January 2015 the club presented $3,600 in scholarships to high-school students who had competed for prizes in piano, strings, vocal, and woodwinds divisions. In addition, a generous bequest by former longtime member Evelyn Bonar Storrs provides approximately $30,000 each year in scholarships to 12 to 14 advanced college-level pianists attending area colleges. After Storrs died in 1989, a pleasantly surprised club learned through her will that she created the endowed scholarship fund, “to express my appreciation for the enjoyment and pleasure in having been a member of the Musical Club of Hartford.” The winners of both scholarship programs perform in two free concerts each year. In 2012 former club president Marjorie Jolidon left $200,000 to The Musical Club to support yearly concerts by invited guest artists; the program was renamed the “Jolidon Concert Series” in her honor.

Funds are raised annually to provide scholarships to high school and local music students. In January 2015 the club presented $3,600 in scholarships to high-school students who had competed for prizes in piano, strings, vocal, and woodwinds divisions. In addition, a generous bequest by former longtime member Evelyn Bonar Storrs provides approximately $30,000 each year in scholarships to 12 to 14 advanced college-level pianists attending area colleges. After Storrs died in 1989, a pleasantly surprised club learned through her will that she created the endowed scholarship fund, “to express my appreciation for the enjoyment and pleasure in having been a member of the Musical Club of Hartford.” The winners of both scholarship programs perform in two free concerts each year. In 2012 former club president Marjorie Jolidon left $200,000 to The Musical Club to support yearly concerts by invited guest artists; the program was renamed the “Jolidon Concert Series” in her honor.

Today The Musical Club of Hartford continues its long-standing traditions of gathering to explore and celebrate music with meetings during which members perform, hear lectures, and enjoy concerts by professional performers. The Musical Club of Hartford has remained true to its mission and to its 125-year history of connecting people with live music, supporting, cultivating, and nourishing that relationship that brings so much pleasure and value to modern life.

Jennifer LaRue is the editor of Connecticut Explored.

Jennifer LaRue is the editor of Connecticut Explored.

Priscilla Rose’s history, along with a second volume, compiled by Jane Bartlett and Betty Ohlheiser and published in 1991 and a third, by Bartlett, Ohlheiser, and Laura Holleran and published in 2001, is the source of much of the material included here. Readers interested in full lists of Musical Club performances, presidents, and charitable gifts will find that information fully documented in those three volumes.

Explore!

The Musical Club of Hartford’s 125th Anniversary season is called “Autographs” for the many programs in the club’s archives signed by the performers. This season’s member programs will be a tribute to some of those musicians: opera singer Mme Schumann-Heink, Marian Anderson, Arnold Dolmetsch, Pablo Casals, and Edward MacDowell, among others. Membership, which includes free admission to all events, is open to everyone. For more information visit musical-club-of-hartford.org.

April 14, 2016. Dual recital by internationally renowned pianist Mariangela Vacatello and her husband, noted organist Adriano Falcioni, including a new arrangement they have made of Stravinsky’s Firebird.