“Afternoon Illustration Class”, 1914-1915 brochure of the School of the Art Society of Hartford as the Hartford Art School was then known. Hartford Art School archives, University of Hartford

By Elizabeth J. Normen

(c) Connecticut Explored, Summer 2003

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

The World’s Fair in 1876 celebrating the United States’ centennial drew 10 million people to Philadelphia’s Fairmont Park to tour five mammoth buildings showcasing the best in cultural and industrial innovation from around the world. Reverberations from the exhibition were felt 200 miles away in Hartford triggering the formation of the Hartford Art School (now part of the University of Hartford and celebrating its 125th anniversary this year) and the resuscitation of the Wadsworth Atheneum’s moribund art gallery.

The link between the Centennial Exhibition and the founding of the Hartford Art School was Candace Wheeler (1827-1923) of New York. As Amelia Peck documents in Candace Wheeler: The Art and Enterprise of American Design, 1876-1900, Wheeler would later have other Hartford connections as well: she was interior decorator (with Louis Comfort Tiffany) of Mark Twain’s house in Hartford, and she engaged the Cheney Silk Mills of Manchester to manufacture her textile designs. But in 1876, after attending the Centennial Exhibition and being most impressed by Britain’s exhibit of the Aesthetic Movement, especially the fine embroideries and textiles of the Royal School of Needlework, Wheeler, a middle-class married woman, conceived of an idea to help women left destitute by the Civil War. Those who lost fathers, husbands, and brothers needed a means of earning a living acceptable to Victorian society-and options were few. Wheeler’s idea was to create respectable jobs for women in the domestic arts of needlework, china painting, and other crafts, and develop markets for this work.

As Candace Wheeler was founding the New York Society of Decorative Arts in 1877, she put a call out to women in cities across the nation to establish auxiliary societies. Hartford was among the first six cities to answer the call. The other cities were Chicago, St. Louis, Detroit, Troy (New York), and Charleston. Kathleen McCarthy, in Women’s Culture, called this “the first major artistic crusade created, managed, and promoted under female control.”

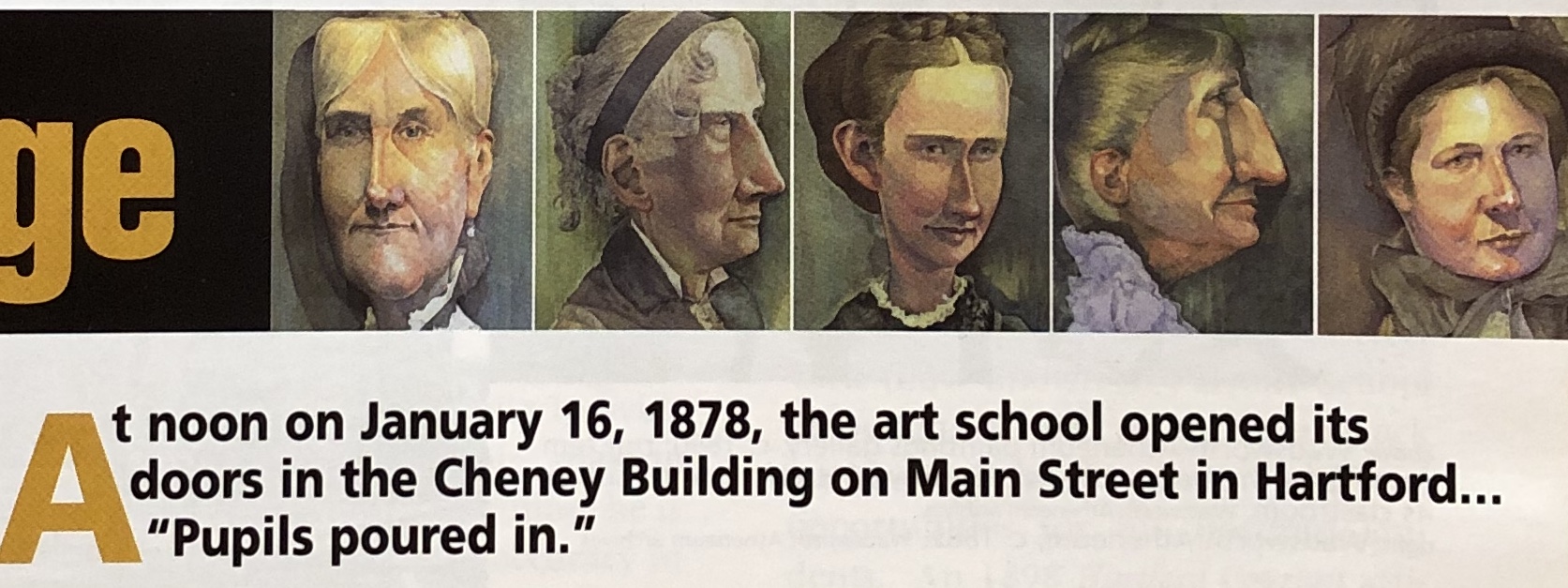

Upon receiving Wheeler’s circular, Hartford’s female civic leaders immediately organized. In June 1877, about 50 of the city’s “public spirited ladies” gathered at the home of Lucy Perkins. Among this group was Elizabeth Colt, then owner of Colt Patent Firearms Manufacturing Company, who had visited the Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia and would become the Hartford Society’s first president. Also in attendance were author Harriet Beecher Stowe, Olivia Clemens, wife of Mark Twain, Susan Warner, wife of Charles Dudley Warner of The Hartford Courant , and Mary Bushnell Cheney, wife of Frank Cheney of Cheney Silk Mills. Many of these women were leaders of the city’s benevolent organizations such as the Union for Home Work.

Elizabeth Colt, Harriet Beecher Stowe, Olivia Clemens, Susan Warner, Mary Bushnell Cheney. Illustrations by Alan Carlstrom, courtesy of the Hartford Art School, University of Hartford

From the beginning, the Hartford Society of Decorative Arts took a different tack than the New York Society, focusing instead on art education. Acknowledging that “the strong point of the New York [S]ociety was its sales room where were collected the work of the skilled artists and amateurs of the city, besides the excellent work from country contributors,” Hartford’s organizers decided that there was not a large market in the city for “fancywork.” The secretary recorded, “After much discussion the Society unanimously agreed that elemental instruction by superior teachers was what Hartford needed.”

At noon on January 16, 1878, the art school opened its doors in rented rooms in the Cheney Building (now known as The Richardson, after architect H. H. Richardson) on Main Street in Hartford. “Pupils poured in; [as the minutes recorded]nearly all acceded to the wishes of the Society and deferred painting and decoration until they should take an elemental course in charcoal drawing. Lessons were commenced immediately and within a week the studio was in good working order with large classes three days in the week.”

Two weeks later, at a Society meeting, they admitted they were “embarrassed by [their]own success,” and by March, felt assured that the Society’s “work is no longer an experiment–That a permanent school of art may be established in this city.” Hartford’s student body differed from New York’s as well. Not limited to the middle-class women and girls that Candace Wheeler meant to serve, both male and female students attended Hartford’s art school. Students came from Springfield, Middletown, Manchester, Cromwell, Windsor, and New Britain as well as Hartford. Since a good many needed financial assistance, Mary Jeannette Keney, wife of prosperous merchant Walter Keney, established a scholarship fund that over a five-year period assisted 24 students. Two of these students went on to study in Boston through a scholarship provided by that city’s Museum of Fine Arts. One, Miss Lucy Flanagan, “received more than one prize for her conscientious and talented work,” and later taught in a high school in Boston. Concerning some of the other scholarship students the Society’s minutes noted that their head teacher, “speaking of one of the free pupils called her a genius. A young German boy in this class who cannot prepay for his lessons as a whole hands [in]the amount for each lesson before taking it. Another boy from New Britain is studying directly to support himself as a designer. We have only to mention one of the pupils, Miss Beach, and the beautiful book which she has published to reflect credit on our Society and Prof. Champney’s instruction.”

“Instruction by Superior Teachers”

Wadsworth Atheneum painting gallery, c. 1890; operated temporarily by the Decorative Arts Society and used as its classroom. Inset: Wadsworth Atheneum, c. 1882. Wadsworth Atheneum Archives

The art school’s first teachers were women and little is known about them or their work. A “Miss Taylor” was initially hired to teach the drawing class. “She is a pupil of [Richard Morris] Hunt’s, has had large experience and is highly recommended,” the minutes reported. A friend of hers, Miss Wheelwright of Boston, and Miss Watson of East Windsor Hill were among those who taught decorative arts classes until demand declined a decade later.

Beginning in fall 1878, Hartford’s Society of Decorative Arts hired the first of many distinguished male artists as principal teachers of the art school. James Wells Champney of Deerfield, Massachusetts was described in the Society’s minutes as “a well-respected American painter and member of the National Academy.” Following two stints studying art in Europe, Champney became professor of art history and theory at the three-year-old Smith College in Northampton, Massachusetts. He also did illustrations for Scribners and Harper’s Weekly magazines. Champney traveled from Northampton once a week, holding a drawing class in the morning and lecturing in the afternoon on art and artists. The initial class of 30 students was reported to be “much pleased with their teacher.” They were “vexed and perplexed over perspective drawing but owing to the skill and patient teachings of Prof. Champney are gradually emerging from the mists and doubts.” The Society outfitted its studio with “artistic casts” (reproductions of famous sculpture), and two monthly art journals, The Art Amateur, which was “devoted to the cultivation of art in the household” and Gazette des Beaux Arts, a French journal of European art and studies.

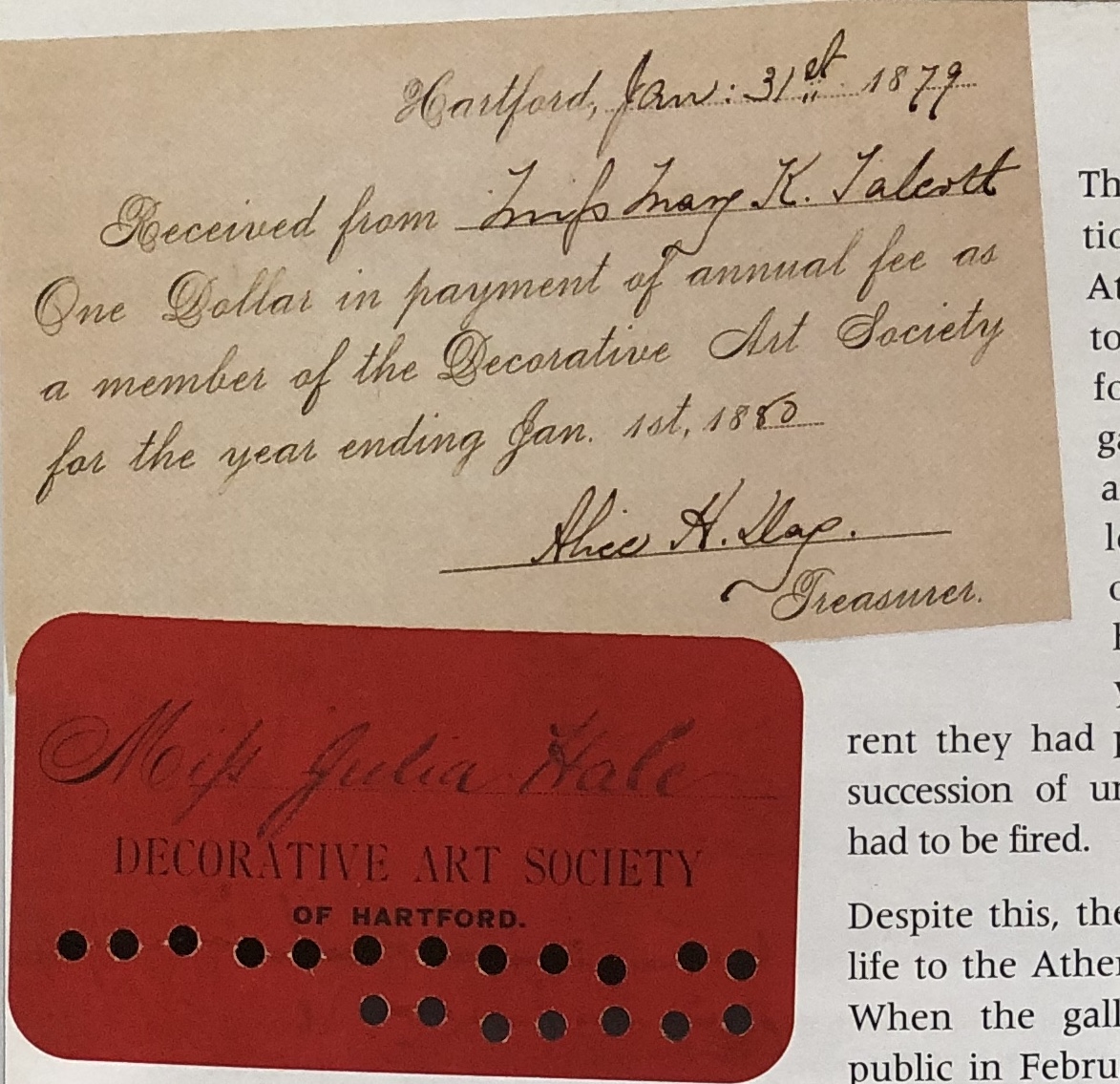

top: Mary K. Talcott’s membership card for the Decorative Arts Society of Hartford, dated January 31, 1879. below: a card punched for 19 drawing classes at the Decorative Art Society of

Hartford’s art school, dated April 17, 1878. The Decorative Arts Society later became the Art Society of Hartford and still later, the Hartford Art School. Harriet Beecher Stowe Center

With his art career on the upswing, Champney resigned his positions with Smith College and the Society’s art school in the spring of 1885. The Society replaced him with Dwight W. Tryon. Tryon (1849-1924) was a native of Hartford whose mother served as custodian at the Wadsworth Atheneum during his childhood. Tryon established a studio in Hartford in 1873, then went to Paris in 1876 and traveled and studied throughout Europe, including at the Ecole des Beaux Arts, until 1881. In 1885, the same year he became principal teacher for the Society’s art school, he, like Champney before him, joined the faculty at Smith College, where he would head the art department until his retirement in 1923. Tryon was impressed by the quality of his Hartford students’ work. Recorded in the Society’s minutes was his report that his students “do stronger and better work than his class at Smith’s [sic]College, and better than the work of the same number [of students]of any school in New York City, two or three of the scholars might even rank with professionals.” He remained principal teacher until 1891, the year he was elected to the National Academy of Design. Tryon was replaced by his protégé, Henry C. White (1861-1952), another Hartford native and future founding member of the Old Lyme art colony. White served as head teacher from 1891 to 1894 and was succeeded by Englishman Dawson Dawson-Watson (1864-1939). The Society’s minutes noted:

Mr. Dawson-Watson, whether one fully agrees with his manner of painting or not, is a most successful teacher, well instructed in the best schools of England and France, and having a thorough knowledge of technique, he believes in making his pupils work out their own manner and methods. He aims to develop each pupil’s individuality, instead of making copyists. At the same time, he is very particular as to accuracy in drawing, and is himself a forcible draughtsman. The improvement of the pupils under him has been very marked, and the work done compares favorably with that of other schools.

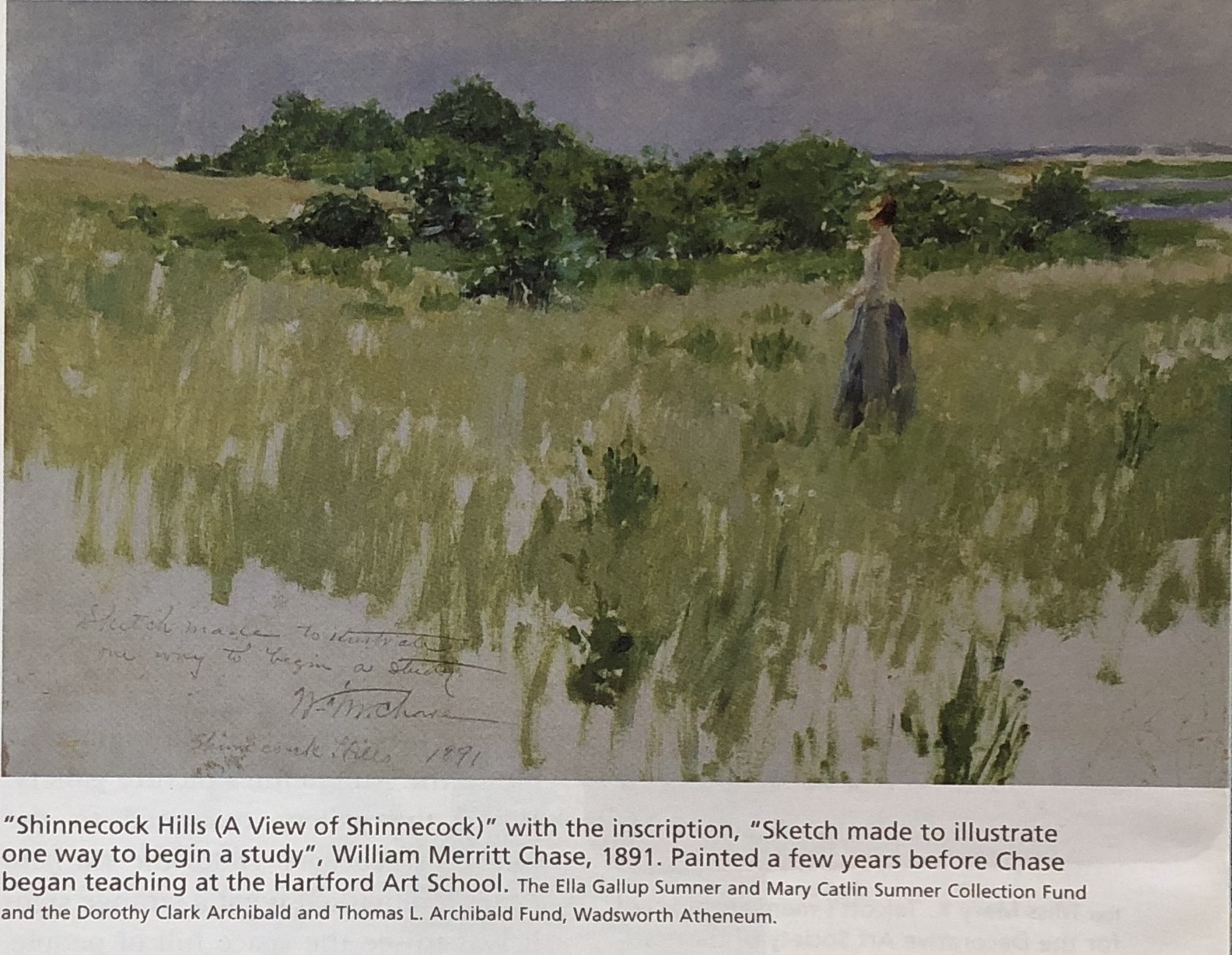

Perhaps the art school’s most distinguished teacher through the turn-of-the-century was William Merritt Chase (1849-1916). His association with the school from 1897 to 1899, while at his artistic height, indicates the level of quality to which the school had risen. Elizabeth M. Kornhauser, curator of American Art at the Wadsworth Atheneum, in “The Spirit of Genius”: Art at the Wadsworth Atheneum called his series of Shinnecock (Long Island) paintings of this period “his finest single achievement and among the most beautiful impressionist landscapes painted in America.” Chase’s art school in New York (now known as Parsons School of Design) as well as his Shinnecock Summer School of Art offered opportunities for his Hartford students. An 1898 Hartford Courant article observed:

The advantages of Mr. Chase’s connection with the art classes of this [S]ociety will not be alone the great one of his teaching here, as he purposes annually to open a year’s scholarship in his New York and Shinnecock school, to the most successful one of his pupils in Hartford-to be known as a “Chase Scholarship.” This will naturally be an incentive to the pupils.

In-Residence at the Wadsworth Atheneum

Initially, the art school operated in rented studio space for its fall and spring sessions, then closed from June to September. The desire for a permanent home was constant. The Society appealed to the Wadsworth Atheneum’s trustees, who had closed the Atheneum’s picture gallery in 1884 for lack of attendance. Having no plans of their own to reopen the gallery, the trustees agreed to let the Society operate the art school in the gallery in exchange for offering open hours to the public to view the Atheneum’s painting collection. The Society was elated: “We have at last been allowed to take as a permanent studio the time honored but long neglected picture gallery of the Atheneum and we hope before this month of January 1886 has passed to be fully established in our new quarters.” In order to facilitate this new joint venture, the Art Society of Hartford (having changed its name from the Society of Decorative Arts in 1884) formally incorporated on March 31, 1886.

The Art Society’s relationship with the Atheneum would prove to be rocky. The Society found the picture gallery much neglected and had to repair the leaky skylight at its own expense. The heating bill for the first year far exceeded the rent they had paid elsewhere, and a succession of undependable custodians had to be fired.

Despite this, the Society brought new life to the Atheneum’s picture gallery. When the gallery reopened to the public in February 1886, the Hartford Courant remarked what a strange sight it was to see the space full of people, when only a short time before it “was so far deserted that the doors were locked upon it several years ago. This was not done to keep people out; they could do that for themselves. It was merely to keep the pictures in, in case the time should ever come when there should be a revival of interest in them and the gallery.” By April, 3,000 people had visited the gallery and through the summer as many as 200 people visited in a day.

No doubt it was the Society’s success that convinced the Atheneum trustees of the art gallery’s potential. The Atheneum’s new president, Reverend Francis Goodwin, raised $400,000 toward a proposed public library (later to become Hartford Public Library) and free art gallery from the city’s leading philanthropists. These included his uncle Junius Spencer Morgan, one of the original subscribers to the Atheneum; J. Pierpont Morgan, Junius’ son; cousins Henry and Walter Keney; Lucy Morgan Goodwin and her sons; and many others in a public subscription drive. In 1890, just four years after the art school had found its “permanent” home, the picture gallery was closed for major renovations. A new two-story brick structure opened three years later to the rear of the Atheneum housing the Watkinson Library upstairs (now at Trinity College) and the new public library downstairs. In the meantime, the Art Society found temporary studio space before returning not to the picture gallery, but to a room in the northwest corner of the Atheneum’s second floor. There it remained until 1900, offering instruction in painting, still life, drawing, cast drawing, and outdoor sketching; models for life study; an annual lecture series; and exhibitions. In 1900 the art school was on the move again, renting space year-to-year. In 1910 Mrs. Charles C. Beach provided space at 28 Prospect Street. In 1920, the Art Society built its own building at 280 Collins Street. Finally in 1934 the art school moved back to the Atheneum, receiving dedicated space in the new Avery Memorial.

Exhibitions, Musicales, and Hard Work

Year in and year out, financing the art school weighed heavily on the Society’s board. Unlike institutions such as the Wadsworth Atheneum, which were formed from substantial contributions by wealthy men that not only built buildings but provided annual income, the Society ran a lean entrepreneurial enterprise, heavily dependent on tuition, membership dues, and event fundraising to make ends meet. Tuition, the largest source of income, did not follow a steady upward trend as the Society had projected, but bobbed up and down each year, with uncertainty about the number of students who would sign up for classes. Membership dues, at $1 per year paid by the Society’s leadership and their friends, were a more consistent but modest source of income, never adding much more than $100 to the Society’s coffers in any given year. The Society also launched various fundraising initiatives. Like the New York Society of Decorative Arts, the Hartford Society held periodic fancywork sales from 1880 to 1890, ending them due to competition from other benevolent organizations’ sales. Lectures and musicales were held to raise operating funds. Mark Twain made benefit appearances every few years; his first one was in Elizabeth Colt’s drawing room in 1880. Charles Dudley Warner of the Hartford Courant, and coauthor with Twain of The Gilded Age, gave several talks, including one on his impressions of the World Columbian Exposition of 1893. Even Candace Wheeler made an appearance in support of the organization she helped spawn.

The Society also organized art exhibitions, initially of works by the art school teachers and students, and then of popular artists of the day. Declaring “It is art indigenous and of our own creation that we need,” the Society featured William Merritt Chase, Dwight Tryon, H. W. Ranger, J. Alden Weir, Cecilia Beaux, and William Gedney Bunce, among others. Admission to these shows provided modest income, yet the Society continually felt the school deserved more public support.

At the turn of the 20th century, the Art Society of Hartford, at 23 years old, still had not accomplished its goal of setting the art school on a firm financial footing. Having only sparse assets and no endowment, the Society relied upon tuition and modest donations and operated with an all-volunteer administrative staff-like most other women’s associations of the day-and was continually challenged by the gap between expenses and what the art school’s students could afford to pay.

Nevertheless, the women of the Art Society of Hartford accomplished a great deal. They established an excellent reputation for their art school, including a record of hiring talented teachers with national reputations. The quality of the students’ work was widely praised, and many of them, both men and women, went on to illustrious careers in art. The Society also brought major figures to Hartford to lecture and exhibit their work.

Equally important, the Art Society played a significant role in the rebirth of the Wadsworth Atheneum as an art museum. Though the Art Society revived interest in the Atheneum’s art gallery, their art school was never on an equal footing with the Atheneum’s other tenants-the Library Association, Connecticut Historical Society, and the Watkinson Library-and continued to be shunted around. Through dedication and commitment the Art Society of Hartford persevered and in 1956 joined with the Hartt College of Music and Hillyer College to form the University of Hartford. Acting within the cultural sphere deemed appropriate for women of education and cultivation, these female entrepreneurs left us the legacy of one of the nation’s most respected art schools.

Elizabeth J. Normen is publisher of Connecticut Explored. She received her masters degree in American Studies from Trinity College with honors in 2000. This article was adapted from an earlier research paper.