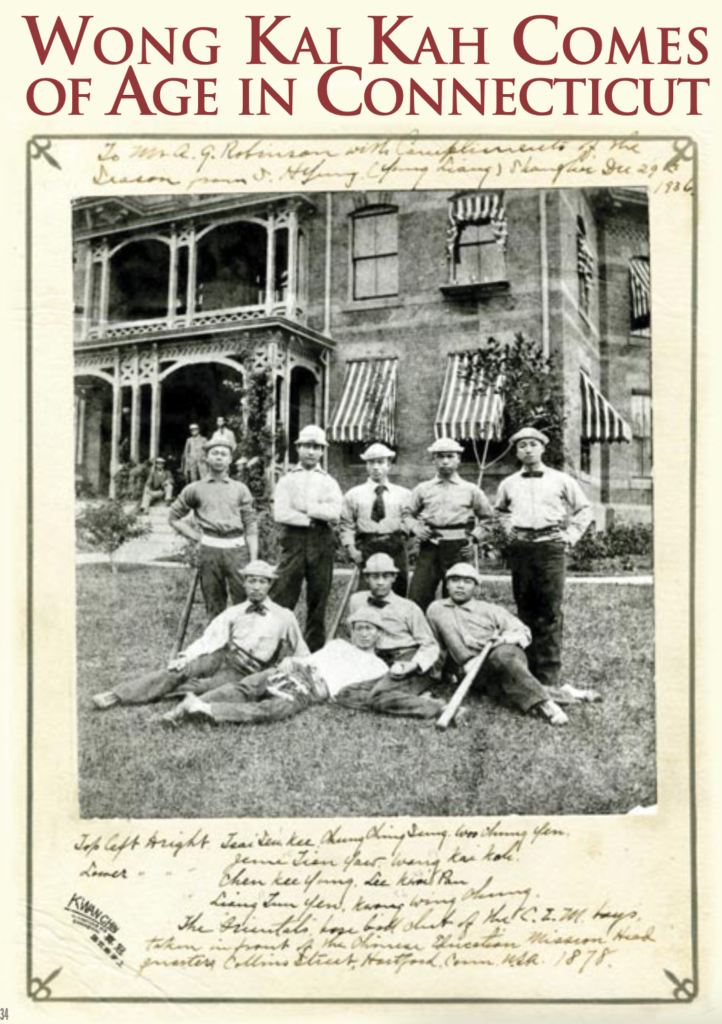

Possibly the first Chinese baseball team posing in front of the Chinese Educational Mission headquarters, Collins Street, Hartford, 1878. Courtesy of Simon Leung. Wong Kai Kah stands at top right. Known as “The Orientals” (although they preferred the name “The Celestials”), the team gained a considerable reputation.

By Simon Leung

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Fall 2021

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

In 1972 my mother traveled from Hong Kong to Stamford, Connecticut to interview for a job. Unbeknownst to her at the time, she followed in the footsteps of her great grandfather Wong Kai Kah, who had made a similar journey from China to Connecticut a hundred years earlier.

Between 1872 and 1875, 120 boys were sent by the Chinese Imperial Government to study English, science, western technology, communication, transportation, and warfare in the United States. The program was the brainchild of Yung Wing, the first Chinese graduate of an American college (graduating from Yale College in 1854). [See “Chinese Exchange Students in 1880s Connecticut,” Summer 2007.] Yung founded the Chinese Educational Mission (CEM), headquartered in Hartford, an initiative of the “Chinese Self-Strengthening Movement” to modernize China and to guard it against the economic and military encroachment of Western powers.

Son of an interpreter at the Shantou customs house in Guangdong, Wong Kai Kah, born in 1860, was part of the first detachment that left for the United States in 1872 at age 12. Like most of his cohort, he came from the middle and merchant classes of the maritime southern provinces. As Edward J. M. Rhodes writes in Stepping Forth into the World: The Chinese Educational Mission to the United States, 1872-81 (Hong Kong University Press, 2011), the students boarded a wooden paddle-wheel steamer in Shanghai, and after stopping in Yokohama, Japan, they embarked on a larger ship bound for San Francisco. Unlike perhaps up to a thousand who traveled in steerage to work as manual laborers in the U.S., the students traveled first-class.

The boys crossed the U.S. on a transcontinental railway system completed just a few years before, the western section of which had largely been built by Chinese laborers. Upon reaching the east coast, the students were dispersed throughout Massachusetts and Connecticut to live with sponsor families. Wong, one of four boys who arrived in Hartford, lived with David Bartlett, the headmaster of the American Asylum (now the American School for the Deaf) and his wife Fannie Bartlett.

Wong’s instruction first took place in the Bartletts’ home. He then attended West Middle School in 1874 and Hartford High School in 1875. The Asylum Hill neighborhood in Hartford was where Yung Wing had established the mission’s headquarters. Before 1878, when the Chinese legation was set up in Washington, the mission was a de facto representative of the Qing Court in the U.S.

Ever-ready to make a speech even “when shaken from a sound slumber,” Wong acquired an American nickname, “Breezy Jack,” for his extemporaneous eloquence, Rhodes documents. He attended Yale, where he studied Latin, Greek, mathematics, geography, and rhetoric.

By 1880 the Qing Court had begun to question the worth of the mission and the resulting Americanization of the boys. There were also, by then, torrents of anti-Chinese feeling in the U.S., culminating in the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. For the first time in history, a race was barred from entering the United States. In 1881, the CEM students were recalled back to China.

That was not the last of Wong Kai Kah in America. After the Qing Court was shaken by the Boxer Rebellion, China reinvested in modernization and relations with the West and sent Wong back to the United States in 1903 as the Vice-Commissioner of the Chinese Pavilion for the 1904 World’s Fair in St. Louis. Later, he represented China at the signing of the Treaty of Portsmouth in 1905, which took place in Kittery, Maine and officially ended the Russo-Japanese War.

If one rummages through the internet archives, as I do, these American years yield speeches and essays in which Wong reflected on his American experiences. In one lecture, “New England Education from the Standpoint of an Oriental” for the New England Society of St. Louis (December 21, 1903), he said:

We came here total strangers to the country, to your manners, your customs, even your language. … We were not looked upon as strangers or students coming here to study; we were treated in each instance as one of the family. … Our young minds were then filled with love and reverence for our own parents, and transferred that love and reverence to the old teachers of New England… . After the year 1881, after I was recalled, you had this Anti-Chinese Act. … (Y)our government asked our government to make a treaty … to assist your government in limiting the Chinese emigration. …. I do not want to offend you, but I say dare your government put such an affront upon a European nation? I believe not. At least, you never did!

Wong returned to China in 1905 and died in an accident in Japan in 1906. The Chinese Exclusion Act was repealed in 1943 by the Magnuson Act, but severe immigration restrictions and discrimination continued into the 1960s, the vestiges of which are felt today.

Simon Leung is an artist who lives in Brooklyn and Los Angeles.

Explore!

Chinese Exchange Students in 1880s Connecticut,” Summer 2007

GO TO NEXT STORY

GO BACK TO FALL 2021 CONTENTS

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!