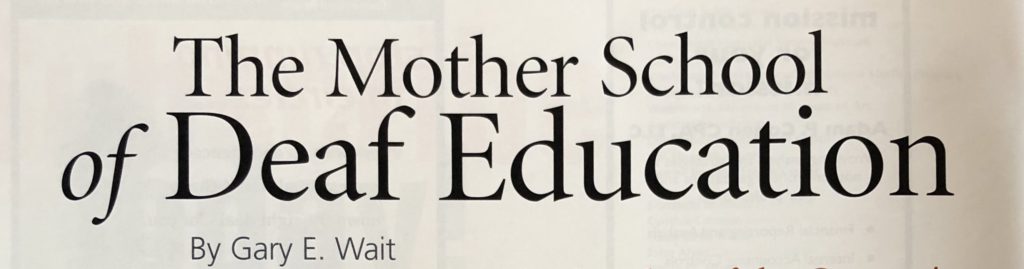

Between 1821 and 1921, the American School for the Deaf was located on Asylum Avenue, at the junction of Farmington Avenue. This cabinet-card view of the “Old Hartford” campus was taken c. 1890. American School for the Deaf

By Gary E. Wait

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Spring 2005

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

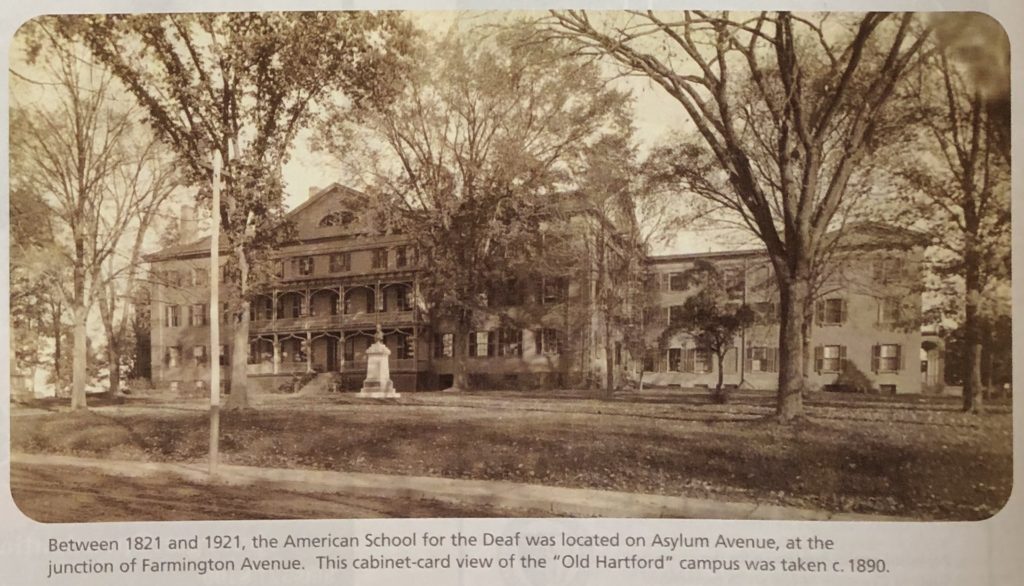

When the founders of the Connecticut Asylum for the Education and Instruction of Deaf and Dumb Persons, as the American School for the Deaf was originally known, opened their doors to a class of seven students on April 15, 1817, they were embarking on a venture unique in the history of the young republic. Occupying rented quarters in the City Hotel building on Main Street in Hartford, which stood approximately across the street from the Wadsworth Atheneum, the Asylum would grow in size and influence to become the “mother school” of deaf education in America.

The story of the American School for the Deaf (ASD) actually began a decade before its opening. In 1807 the two-year-old daughter of Dr. Mason Fitch Cogswell, a noted Hartford physician, contracted spotted fever which left her deaf. But if disease had robbed Alice Cogswell of her hearing, it had not taken her intellect nor her zest for life. As she grew it became evident to her parents that she might yet lead a full and meaningful life if only the doors of communication could be opened to her. That in itself was revolutionary at an age when, at least in America, most people regarded deaf persons as doomed to intellectual ignorance and hopeless dependence. Fortunately Alice’s parents and their Hartford neighbors took a more imaginative view. Aware of experiments in deaf education being carried on in England and France, Dr. Cogswell procured instructional materials from l’Abbe Roche Ambroise Sicard, head of the l’Institution Imperiale des Sourds-Muets, a school for deaf-mutes in Paris, by which he hoped to begin the process of educating his daughter.

Meanwhile, Alice’s sisters had been enrolled in a private school for “young ladies of good family” conducted by Lydia Huntley, (later to gain fame as the poet, Lydia Huntley Sigourney), and the kindhearted Huntley allowed Alice to accompany her sisters. Herself an innovator in the field of education, Huntley learned the manual alphabet, probably from the materials sent by l’Abbe Sicard, and employed it to teach Alice words, then phrases, and finally sentences to express ideas, feelings, and observations. By 1815 Alice was writing coherent paragraphs which, if not yet strictly grammatical, were the comprehensible expressions of an active mind. At this time, the Cogswells’ neighbor, Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet (1787-1851), a young ministerial student who took an interest in Alice, found that she readily grasped the relationship between the written word and the object for which it stood.

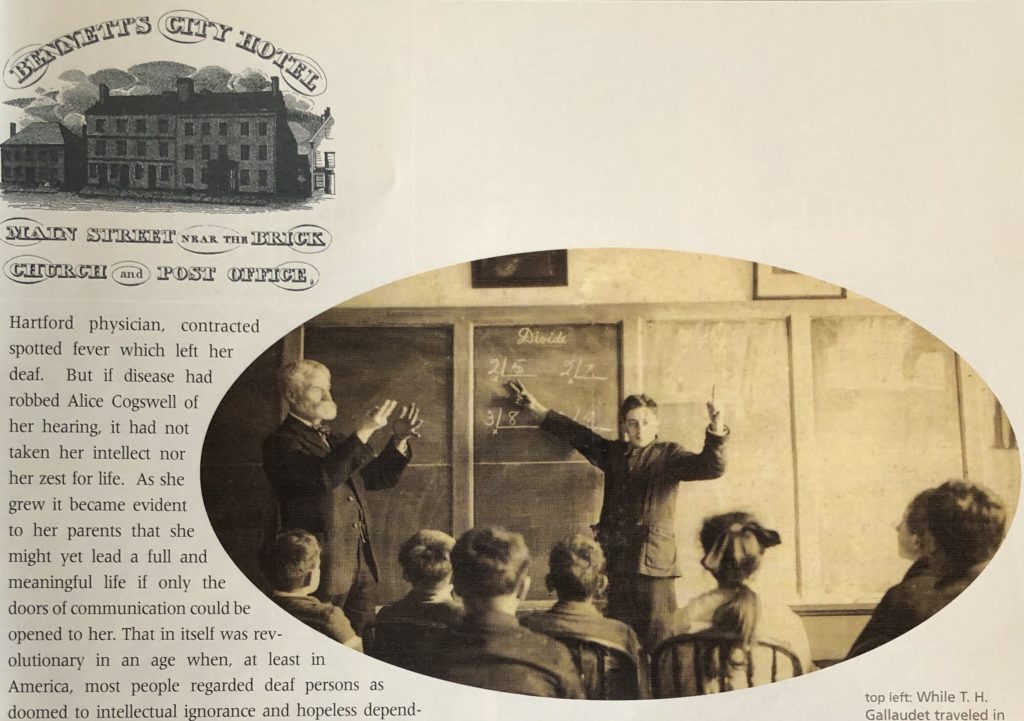

top left: Bennett’s City Hotel, c. 1820, the first location of the school. below: A junior high class in mathematics, c. 1900. The teacher, John Crane, who was also deaf, is shown teaching by sign language. American School for the Deaf

Thus encouraged, Dr. Cogswell conceived the idea of establishing a school in America, based on European models, for the education of deaf persons. Having raised a fund for this purpose among his Hartford neighbors, Dr. Cogswell persuaded Gallaudet to journey to Europe to acquaint himself with the techniques employed in the deaf schools there. Rebuffed by the English practitioners to whom he first appealed, Gallaudet eventually journeyed to Paris, where he was trained in the French method of teaching by manual gesture (i.e., signing). There, also, he formed a friendship with a young deaf teacher, Laurent Clerc (1785-1869), whom he persuaded to join him in founding a new school in America.

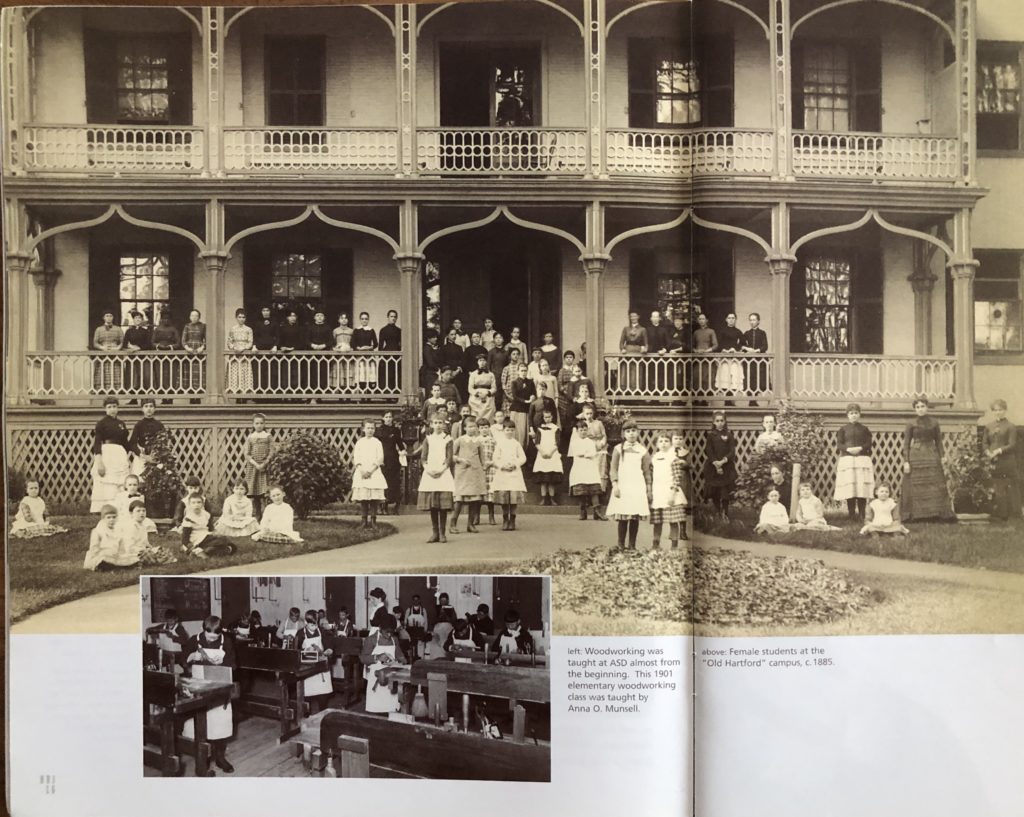

The curriculum of the fledgling school in Hartford was at first quite limited in scope, embracing just two subjects: communication skills through reading, writing, and manual sign; and religion – part of the object in starting the school being the saving of souls. For adolescents never before subjected to classroom instruction, however, this curriculum proved confining, as well as impractical, as it did not equip students to earn an independent living once they completed their studies. Always cautiously innovative, the school soon met this challenge by adding vocational subjects: woodworking, tailoring, shoemaking, and later printing for the boys and domestic skills and mantua-making for the girls.

But even this did not serve the needs of all. George H. Loring, the second student to enroll in the new school, was a case in point. Scion of a wealthy Boston mercantile family, Loring proved to be exceptionally bright and intellectually curious, and both he and his family would have considered his engaging in a trade rather beneath them. Once again the school proved imaginative in its response, gradually adding academic subjects to the curriculum: French and geography at Loring’s urging, general science by the early 1830s, history, mathematics, and drawing in turn. By 1852, responding to a rising proportion of academically talented students, ASD inaugurated its first high school class, and in 1864 furnished the first student Melville Ballard, for the newly chartered collegiate department of the Columbian Institution for the Instruction of the Deaf (now Gallaudet University).

Throughout the nearly two centuries of its existence ASD has continued to respond in innovative ways to evolving educational theory and to the changing needs of its students. With the discovery that language skills are most readily acquired in infancy and early childhood, the age of admission has been gradually lowered from the original age of twelve, to eight, and now to prekindergarten (about age four); and even this supplemented by a “birth-to-three” home outreach program. At the other end of the continuum, an adult vocational program allows post-high school deaf and hard-of-hearing persons to acquire additional work skills and assists them in finding employment.

top: Female students at the “Old Hartford” campus, c. 1885. below: Woodworking was taught at ASD almost from the beginning. This 1901 elementary woodworking class was taught by Anna O. Munsell. American School for the Deaf

Traditional course offerings have also been modified to meet changing needs. Printing is still taught, but over the years manual typesetting gave way to linotype, which in turn was replaced by computer printing. Likewise, autobody repair and computer graphics have replaced once-popular subjects like mantua-making and typewriter repair. And while religion is no longer part of the curriculum, human values and public service are. The typical school year will see numerous staff and student projects to assist charities or the victims of tragedy. To bridge the gap between the deaf and hearing communities, public signing classes are offered, as well as communications classes for the families of deaf children and school staff.

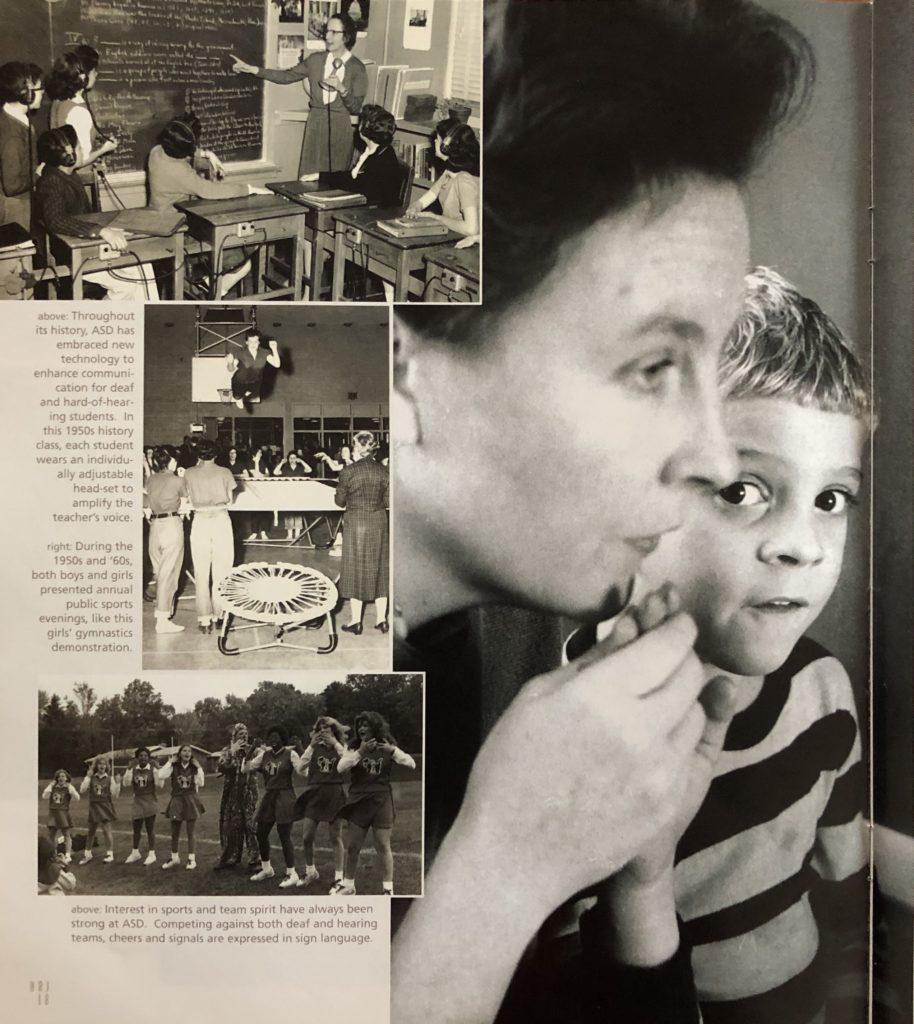

right: For children receptive to it, speech reading and articulation are taught, as well as sign language. Here teacher Carolyn T. Halberg is helipng a student understand the mechanics of producing the sounds that make up speech.

Thus, while ASD enjoys a proud heritage it does not live in the past. Employing new information imaginatively and responsive to an ever-changing social and work environment, ASD continues to serve the current and anticipated needs of the deaf community.

Gary E. Wait was archivist for the American School for the Deaf.

Explore!

“200 Years of Deaf Education,” Fall 2017

Read more stories about childhood and education on our TOPICS page.