(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Spring 2022

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

In 1845 The Hartford Courant published a short article about William Lanson who, it said, was commonly known as “King Lanson.” It failed to note that Lanson was also one of New Haven’s most noted artisans and community leaders. By this time in Connecticut history, the presence and importance of “Kings” or “Governors,” as leaders in the Black community were called, was firmly entrenched in the minds and hearts of both African American and white residents. [See “Black Governors, 1780 – 1856,” African American Connecticut Explored (Wesleyan University Press, 2014.)]

The election of African Kings and Governors began long before the end of enslavement in Connecticut. Like elsewhere in the colonies, slavery existed early in the tenure of the Dutch and English in colonial Connecticut. With more than 5,000 enslaved people at one point, Connecticut had the largest slave population in New England. Though Connecticut began a program of gradual emancipation after the War for Independence, as Lucy Gelman notes in “William Lanson Statue Taps into City’s Black History” on NewHavenArts.org, Connecticut still had people listed as enslaved in the 1820s.

Lanson was a part of a long tradition of African American artisans in New England and the country as a whole. How he came by his skills is not fully known. African American artisans provided a pool of skilled labor from the colonial period to the 19th century that bolstered the commercial and economic growth of the nation. While Lanson’s work on construction projects—most notably an extension to Long Wharf and a section of the Farmington Canal—was part of this effort, he seized the opportunity, like other African American artisans, to seek physical, economic, and religious freedom for himself and his community.

Lorenzo Greene, an African American and noted historian born in Ansonia, Connecticut, wrote of such artisans in the Negro in Colonial New England, 1620-1776 (Kennikat Press, 1966). In one example from 1661, Greene documents that Thomas Dean of Boston decided to employ an African American as a cooper, which drew the ire of white mechanics. By September 5, 1661, white city leaders ordered Dean to discontinue the work of the African American in coopering or any other skilled occupation.

While skilled in areas needed by a growing economy and society, the artisan and skilled class of which Lanson was a member in the early 1800s served as a conduit for producing African American leaders. Denmark Vesey, Nat Turner, Richard Allen, and Absalom Jones all belonged to the class of African American mechanics in the South. In the example of Denmark Vesey of South Carolina, his diligent work as a carpenter enabled him to become well-off by the standards of the early 19th century. In 1822 Vesey organized enslaved and free Blacks, church leaders, and craftsmen in an effort to seize the city of Charleston, South Carolina. Vesey’s plot was revealed by Peter Poyas, one of the local Blacks with knowledge of the plans. White political leaders and military leaders ruthlessly crushed the plot, executed Vesey, and punished others involved by selling them away to plantations in other areas.

Rev. James Pennington, who later lived in Hartford and served as pastor of the congregational church for African Americans, now Faith Congregational Church in Hartford, learned the skills of a blacksmith and stone mason in Maryland. [See “James Pennington: A Voice for Freedom,” Winter 2012-2013.] Clarence Lusane, a scholar of African American history, wrote that African American labor, skilled and unskilled, built the U.S. Capitol, White House, and city of Washington, D.C.

Thus Lanson was by no means a singular example of an early Black skilled artisan and community leader. Though no specific date has been found for his arrival in New Haven, by the early 19th century he began to acquire property and build a respected name for himself in the city. Historian Katherine Harris, in “William J. Lanson, Triumph and Tragedy” (The Amistad Committee, 2010) and in African American Connecticut Explored, notes that by 1820, New Haven’s African American community numbered 600, “but the true number may have been undercounted.” In 1807 Lanson acquired property in the now trendy area of Wooster Square. At the time of his purchase, residents used the land for plowing contests.

detail, B. F. Smith, birdseye view of New Haven from Ferry Hill, with the long wharf, center, c. 1849. Connecticut Historical Society, Hartford

Lanson was the key figure in two huge construction projects that changed the future of the city: the extensions of Long Wharf and the construction of part of the Farmington Canal. In 1811 the extension of the wharf in New Haven was one of the most impressive engineering accomplishments in the city’s history to that date. Lanson completed the final 1,350-foot addition, making it possible, due to New Haven’s shallow harbor, for larger cargo ships to dock. Lanson, with a work crew composed of African-American men, first cut stone from Blue Mountain in East Haven and then placed the material on scows built for the construction project. The scows transported 25 tons of stone for the project.

While the wharf extension aided shipping, “business offices, ship chandlers, rope walks, blacksmith shops, bars, and boarding houses all found a place on the wharf,” which led to the wharf’s emergence as a “commercial and business hub,” notes Harris. Lanson and his crew also built “nearly all of the East Haven Bridge.”

Lanson had clearly found favor with prominent city political and religious leaders. Reverend Timothy Dwight, the highly respected president of Yale College, referred to Lanson and his brothers in an 1811 report about New Haven as “honourable proof of the character which they sustain, both for capacity, and integrity, in the view of respectable men.” As a result, Harris observes, New Haven strengthened its commercial ties to Europe, the Caribbean, and the American South. “This stimulated the demand for Connecticut carriages, clocks, rubber boots, arms, and hardware.”

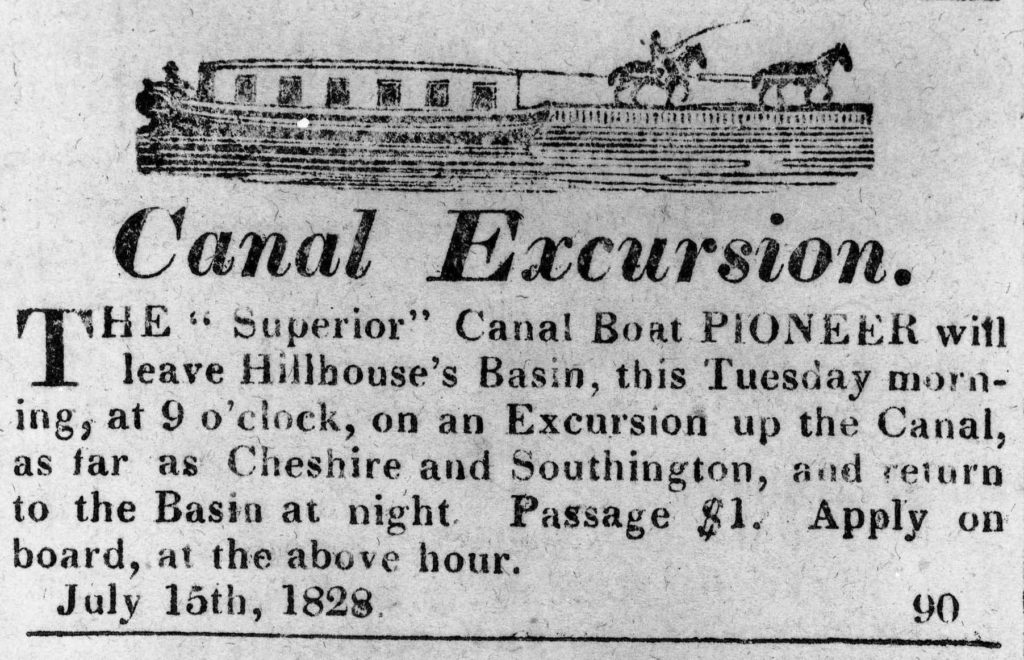

Inspired by the completion and financial success of the famed Erie Canal, powerful Connecticut residents formed the Farmington Canal Company in 1822 to construct a canal from New Haven harbor to the Connecticut River at Northampton, Massachusetts. [See “The Ill-Fated Farmington Canal,” Spring 2008.] In 1825 politician and abolitionist James Hillhouse, who served as superintendent of the project, hired Lanson to build the New Haven section. In 1827 Lanson’s workforce of 20 to 30 African American men traveled to Blue Mountain for the strenuous work of quarrying the stone for the canal walls. Lanson remarked in his self-published William Lanson’s Statement of Facts Addressed to the Public (1850) that the walls were “two thousand and ten feet in length, eight feet thick at bottom, six at top, and eight feet high.” Lanson indicated that the “canal project cost him $2,600,” but he refused to complain. By the 1830s, according to his son Isaiah Lanson, in a published transcript of court testimony, Lanson’s worth was around $20,000.

Though his work on the large construction projects brought recognition from prominent white leaders, Lanson’s growing wealth also came as a result of the diversified business interests he held. He owned property in an area of New Haven known as “New Guinea,” a short distance from an Irish community of the city. In an additional business move, Lanson bought an old slaughterhouse and constructed “sheds and barracks for his tenants and customers,” according to Robert Austin Warner in New Haven Negroes: A Social History (Arno Press, 1969). A livery stable, store, and hotel were also part of his interest. His Liberian Hotel, which lodged people in a section of the city called New Liberia, once had furnishings valued at $1,000, Harris found.

A Community Builder, Too

Lanson became a respected community and political leader, too. In 1825 he was elected “African King” of New Haven, a title reserved for respected African American community leaders throughout New England in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Like African Americans in Hartford, New Bedford, Massachusetts, and other parts of New England, New Haven’s African American community fought with vigilance against slavery. William Lanson’s family, both male and female members, openly challenged the presence and persistence of the institution. In 1838 Laban Lanson, Harriet Lanson, Elizabeth Lanson, and Nancy Lanson signed petitions in support of enslaved people who fled the South. Lanson’s family also sheltered enslaved runaways from the South and coordinated private religious gatherings for runaways.

One of his best-known cases was his support of William Grimes, a fugitive who escaped from slavery in Georgia. [See “Rediscovering William Grimes, the Runaway Slave,” Winter 2021-2022.] In his autobiography, The Life of William Grimes, Grimes recalled that he found employment in New Haven with Lanson family members Isaac (William’s brother) and Abel (William’s nephew) at their livery stable, and also worked and quarried stone for Abel.

When it came to the social, religious, and political freedom of African Americans, William Lanson, while serving as African King, supported the African Ecclesiastical Society, later the Dixwell Avenue Congregational Church. Along with Bias Stanley and Reverend Amos Gerry Beman, Lanson argued for exemption from taxation if African Americans did not have the right to vote. [See “No Taxation without Representation,” Spring 2016.] In stories published in the Columbian Register, Lanson boldly asserted that African Americans in New Haven and the country were an “industrious” and quality people. The state of Connecticut would not grant universal male suffrage until after the Civil War ended.

Marker at an entrance to the Farmington Canal Heritage Trail, New Haven, 2021. photo: Elizabeth J. Normen

The Tide Turns for Lanson

As Lanson became more prosperous, he also became the face and target of white people’s fears of Black progress in New Haven. Though there is no record that he supported the proposal in 1831 to found a “negro college” in New Haven, Lanson was flayed in the press anyway for having done so. His own fortunes then took a downward turn, too.

The suggestion of New Haven as the location of the “negro college” received support from Simeon Jocelyn and Arthur Tappan, prominent white abolitionists of New Haven, and famed abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison. Organizers, both white and African American, wanted to develop a curriculum with “manual labor, connecting agriculture, horticulture, and mechanic arts with the study of literature and sciences,” according to Harris. Lewis Tappan, along with Jocelyn and his brother Arthur Tappan, held the belief that New Haven’s white community and Yale College leadership would welcome the establishment of the “negro college.” They even thought that Yale professors might willingly lecture to students. Arthur Tappan bought land for a building and offered $1,000 in seed money to establish the college.

But at a September 10, 1831 public meeting at City Hall, city officials passed two resolutions in opposition to a “negro college” by 700 to 4. [See “Cast Down on Every Side: The Ill-Fated Campaign to Found an ‘African College’ in New Haven,” Summer 2007.] As Harris and Warner both note, many of the most vicious attacks against the proposed college and Lanson were published in the Connecticut Herald, New Haven Palladium, Connecticut Journal, and Columbian Register.

Though opponents defeated the attempt to build a “negro college,” members of the Lanson family sought education at Prudence Crandall’s school in Canterbury, Connecticut, after it opened for “young colored misses.” On May 20, 1834, Harriet Rosette Lanson, William’s niece, studied at the school for a year; sadly, she died in 1835. Jocelyn, who had helped to pay her tuition, wrote the obituary, published in William Lloyd Garrison’s Liberator.

In 1831 a white mob stormed through the New Liberia section of New Haven and “dragged out and arrested” local whites. Though the area reportedly was known for harboring vice, prostitution, and race mixing, the police failed to locate evidence of prostitution. Police Officer Jesse Knevals provided testimony in court that he had not observed “bad conduct in Lanson’s houses.” Both Lanson and his son strongly argued that the elder Lanson had no connection to illegal activity.

Even so, a news story 14 years later in The Hartford Courant, among other papers, gloated that William Lanson, “the former proprietor of the Liberia Hotel, and the rascal who has caused much trouble in this city for the last few years, has been found guilty, convicted and sentenced to 6 months imprisonment in the County Jail, and to pay a fine of $50.” In his defense, the Lanson family responded that he rented the space to “two or three different tenants, and in their hand it got a bad name.”

William Lanson died in 1851, but his legacy was set in stone and in the hearts of his community long before his death. Like most African American artisans, Lanson was forever a builder. The extension of Long Wharf and work on the Farmington Canal are clearly his most impressive construction accomplishments, but he built beyond structures in his quest for voting rights, religious freedom, care for the indigent, and housing for those in need. Though criticized and targeted, Lanson built internal strength to stand and fight for his community and himself. Even today, few business people and artisans can make the claim that they hired 20 to 30 crew members to complete a construction project. For fugitives fleeing the South, Lanson, with the support of other abolitionists and anti-slavery advocates, built a safe space for runaways inside New Haven’s African American community. He understood that artisans need to build in whatever space they occupy. A statue in his honor erected along the Farmington Canal Trail in 2010 serves as a reminder that William Lanson built beyond structures.

Stace Close is professor of African American History at Eastern Connecticut State University. He is a contributor and co-editor of African American Connecticut Explored (Wesleyan University Press, 2014) and last wrote “Greater Hartford NAACP: 100 Years in the Freedom Struggle,” Fall 2017.

GO TO NEXT STORY

GO BACK TO SPRING 2022 CONTENTS