(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Winter 2021-2022

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

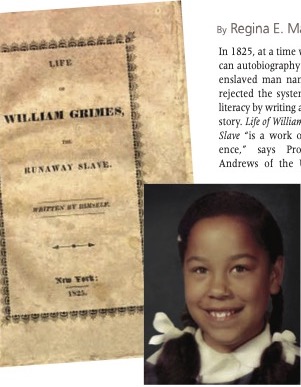

In 1825, at a time when African American autobiography was rare, a formerly enslaved man named William Grimes rejected the system that denied Black literacy by writing and publishing his life story. Life of William Grimes, the Runaway Slave “is a work of literary independence,” says Professor William L. Andrews of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, an expert on early African American autobiography. In his groundbreaking book To Tell a Free Story: The First Century of Afro-American Autobiography, 1760-1865 (University of Illinois Press, 1988), Andrews pronounced Grimes the author of the first fugitive slave narrative in American letters—that is, by someone who escaped slavery in the South. Equally important, Grimes wrote and published his story himself.

left: Life of William Grimes, the Runaway Slave (New York, 1825). Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Yale University. right: Regina “Gina” Brown in 1971 when her Aunt Katherine told her the story of a man named Grimes.

Courtesy of Regina Mason

Surprisingly, this man’s truth became largely forgotten until his narrative reached across time to me—168 years after it was published. For five generations, fragments of family stories had kept the memory of a man named Grimes alive until I was able to piece together a rich history that connected to William Grimes the author. None of the elders in the family—not even Aunt Katherine the family historian—knew that our Grimes had penned his life story.

In 1991, years before the Internet, I had begun to conduct genealogical research to see if I could find truth in a story my Aunt Katherine had told me when I was 11, in 1971. It was a thin tale that amounted to three little clues. She told me that we had an ancestor from New Haven, Connecticut named Grimes who had a connection with the Underground Railroad. I was just learning about American history in school, and the reference to the Underground Railroad was huge. It signaled an anti-slavery attitude that had me, a child, wondering who Grimes was. My curiosity persisted into adulthood.

Twenty-three years later I found a William Grimes in Charles L. Blockson’s The Underground Railroad (Berkley Books, 1989) who, after escaping slavery in Savannah, Georgia, made his way to New Haven, Connecticut. Blockson’s bibliography revealed that Grimes had written his life story and published it himself. I further learned that Grimes’s narrative had been republished in 1971 in the anthology Five Black Lives: The Autobiographies of Venture Smith, James Mars, William Grimes, The Rev. G. W. Offley, and James L. Smith (Wesleyan University Press).Cody’s Books in Berkeley, California had three copies for sale; I bought all three.

As I read this man’s story, the language astonished me. Nothing I had ever read about slavery in America prepared me for this explosive text. With only a hunch that he was my Grimes, I searched U.S. Federal Census records in Connecticut for familial clues but was unable to solidify a connection.

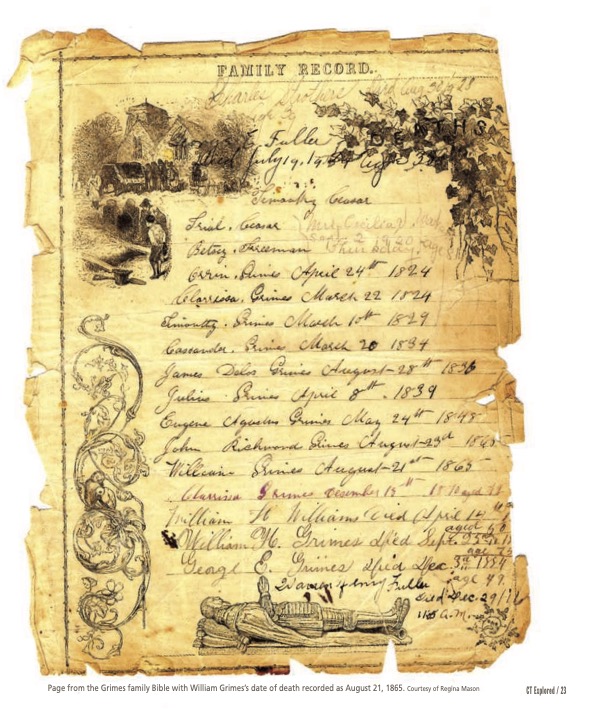

As I attempted to get beyond the brick wall that stymied my research, I had no idea that Aunt Katherine had been conducting her own investigation. On Memorial Day 1993 she brought home compelling pages that she had found tucked inside a frail family Bible stored for decades in her sister’s attic in Portland, Oregon. There, among rows and rows of cursive script, was the name William Grimes, with a recorded death date of August 21, 1865. Another name emerged that would strengthen the connection—his wife Clarissa Caesar, whom Grimes had named in his book. Without a doubt, William Grimes, author of Life of William Grimes, the Runaway Slave, was my great-great-great-grandfather.

Page from the Grimes family Bible with William Grimes’s date of death recorded as August 21, 1865. Courtesy of Regina Mason

Meanwhile, I had accumulated several documents that expanded upon the story Grimes told. I was convinced that he deserved a new audience. It then became my mission to bring his story to a new generation, but I was unsure how to do it. I wasn’t an academic, and I knew next to nothing about the 100 to 150 published slave narratives, other than having read a few of them. But even with my lack of education in the field, Professor Andrews, whom I had been communicating with, had a plan. He proposed we team up as co-editors to produce a new edition of Grimes’s narrative. In 2008 Oxford University Press published our authoritative work, Life of William Grimes, the Runaway Slave (revised edition).

Born in King George, Virginia on the heels of the American Revolution, William Grimes opens his book with pointed sarcasm. “I was born in the year 1784 … in a land boasting its freedom, and under a government whose motto is Liberty and Equality. I was yet born a slave.” His father, Benjamin Grymes, was a wealthy white planter of the estate Eagle’s Nest, and his mother was an enslaved Black woman owned by a “Doct. Steward” on a neighboring plantation. “In all the slave states,” Grimes continued, “the children follow the condition of their mother. I was in law, a bastard and a slave owned by Doct. Steward.”

At age 10, he was sold to Col. William Thornton of the Montpelier plantation in Culpeper County, where he knew no one. He grew to be rebellious, resisting the culture of enslavement at every turn. “I had too much sense and feeling to be a slave,” he wrote. He endured 10 owners—4 in Virginia and 6 in Savannah, Georgia. In 1815, with the help of Black Yankee sailors, he escaped from slavery by hiding among bales of cotton on the brig Casket bound for New York. From there, he made his way to New Haven, where he began a new life, even though he was a fugitive on the run. He lived in constant fear of apprehension, which weighed heavily on his psyche. He was constantly looking over his shoulder, fearful that he would be found out. Whenever he thought his enslaver was on to him, he would uproot to another New England town.

Nine years later, Grimes’s worst nightmare came true. His enslaver found him. By this time, he had married and had children. He was a homeowner and a barber. He had no choice but to give up the deed to his home to pay for a freedom that had not been fully recognized in Connecticut, where slavery was still legal.

Shortly after his ordeal, he began to write his story. To recount his life is to unmask the hypocrisy of American liberty and democracy. Professor Andrews says Grimes’s book reads like a list of “grievances against the United States,” and it was through Andrews that I learned just how precedent-setting my ancestor’s narrative was.

Published in New York in 1825, Life of William Grimes came out two years before the launch of the African-American newspaper Freedom’s Journal and six years before William Lloyd Garrison’s Liberator newspaper. Grimes published before Nat Turner’s Rebellion in Southampton, Virginia occurred in 1831 and before the fiery anti-slavery rhetoric of David Walker’s Appeal to the Colored Citizens of the World was published in Boston in 1829. Frederick Douglass, the most famous African-American abolitionist of the 19th century, was only seven years old when Life of William Grimes appeared.

Indeed, Grimes’s narrative predated the fervor that spilled out of a nationally organized anti-slavery movement, but it is pioneering for other reasons, too. Slave narratives written before Grimes’s were indictments of slavery in the North—not the South. He was the first to write about slavery in the South from the perspective of one who had been enslaved rather than from the viewpoint of the enslaver, who typically controlled the narrative in the South. Surely Grimes’s description of Southern slavery had to have been shocking to any white person who encountered it.

Grimes stated clearly that he had written his narrative “by himself.” This was a bold statement for a Black man to make at a time when literacy was afforded mostly to white people. Moreover, his narrative remains as a definitive example of how difficult it was for marginalized people of color to survive economically under racial oppression in the North, particularly Connecticut, where slavery was legal until 1848.

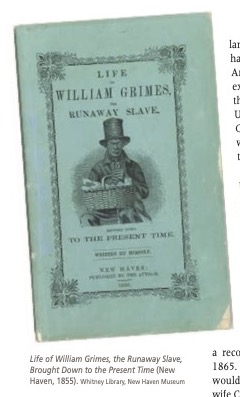

In 1855, when he was about 70, he republished his book to include a chapter chronicling his life in old age. New scholarship by Susanna Ashton of Clemson University, in “Slavery, Imprinted: The Life and Narrative of William Grimes” in Early African American Print Culture (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2012), reveals that this chapter was dictated to Samuel H. Harris, a printer in New Haven.

Grimes’s narrative repeatedly shows how the North was inextricably tied to the system of slavery in the South in one form or another. When Grimes was sold from the Thornton family deeper south to Savannah, Georgia, he was transferred between a succession of businessmen under six different owners, several of whom had ties to New England.

Two enslavers, physician Lemuel Kollock and Oliver Sturges, a business partner in a successful cotton and commission firm, served as president and vice president of a private association called the New England Society of Georgia, as the May 29, 1807 issue of the Columbian Museum and Savannah Advertiser reported. Oliver Sturges, son of the Honorable Jonathan Sturges, L.L.D. of Fairfield, Connecticut, hired out Grimes to work for Philip David Woolhopter, editor and printer of the Columbian Museum newspaper. Grimes was likely exposed there to the power of the printing press—which would serve him well in New Haven.

Arriving virtually on foot from New York City to New Haven, Grimes found refuge in the free Black community there. He found work with Abel Lanson, who owned a livery stable with his brother William Lanson, a leader among his people and a respected entrepreneur and civil engineer. To witness free Black businessmen like the Lanson brothers had to have been a revelation to the fugitive Grimes, and it was through the Lanson family that Grimes found refuge and work when he needed it.

In time, after crisscrossing several New England towns working odd jobs, pursuing business prospects, and avoiding recapture, he returned to Connecticut, where he found consistent employment at Yale College in New Haven and the Litchfield Law School in Litchfield. Both institutions were intellectual and social hubs in their respective communities, drawing men who would become some of the nation’s preeminent politicians, lawyers, educators, and leaders. It was in this environment that Grimes was exposed to and cultivated relationships with men with networking connections and influence.

Life of William Grimes, the Runaway Slave, Brought Down to the Present Time (New Haven, 1855). Whitney Library, New Haven Museum

On August 18, 1817 in New Haven, Grimes married Clarissa Caesar, a free Black woman whose father, Timothy Caesar, served in the American Revolution. Around 1819, upon hearing that a barber was needed in town, the couple left New Haven for Litchfield, where Grimes opened a business grooming the men at the “celebrated Law School, under the direction of Tapping Reeve, Esq.” and the state governor Oliver Wolcott Jr. An industrious man, Grimes purchased property from the renowned Litchfield furniture maker Silas E. Cheney.

Business appeared to be going well in Litchfield, but Grimes thought he could do better in New Haven. After renting out his home, he took out an ad on April 8, 1822 in the Connecticut Herald announcing a joint venture with Thomas Manney on State Street in the business of “coat dressing” and “hair dressing.” This was a risky move. He was still a runaway at risk of being recaptured, especially since he had been spotted a few times before by “friends of his former master,” he notes.

A year later Grimes was embroiled in the fight of his life. No longer able to run from his enslaver, he was faced with an ultimatum: either be sent back to Savannah in chains or purchase his freedom. He chose the latter. Correspondence between Dr. Abel Catlin, who acted on behalf of Grimes, and Francis H. Welman about the transaction survive at the Litchfield Historical Society.

On April 21, 1824 Welman agreed to free William Grimes for $500. “Oh! How my heart did rejoice and thank God… . The thought of being snatched up and taken back was awful… . Accustomed as I had been to freedom for years, the miseries of slavery which I had felt, and knew, and tasted, were presented to my mind in no faint image,” he wrote.

While Grimes rejoiced in his freedom, he had much to say about his lived experiences in enslavement, and he lost no time saying it. No longer living as a fugitive, he was free to write and publish his story, and in the process, he boldly inserted himself into the world of print culture and American history, too.

I hope some will buy my books from charity, but I am no beggar. I am now entirely destitute of property; where and how I shall live I don’t know; where and how I shall die I don’t know; but I hope I may be prepared. If it were not for the stripes on my back which were made while I was a slave, I would in my will leave my skin as a legacy to the government, desiring that it might be taken off and made into parchment, and then bind the constitution of glorious, happy and free America, Let the skin of an American slave bind the charter of American liberty!”

In August 1865, Clarissa Grimes mourned the loss of her husband William and their son, Corporal John R. Grimes of the 29th Colored Regiment, Connecticut infantry. William’s passing garnered some attention. For example, an obituary in the New Haven Daily Palladium, published on August 21, 1865, spoke of a Yale reputation: “Forty years ago [William Grimes] was the head of a prosperous barber shop opposite the colleges. All Yale patronized him and thousands of Yale graduates knew him.”

At the time of Grimes’s passing, indeed since 1852, the Grimes family branches had extended to San Francisco, California. The Grimes roots in New Haven remained firmly planted through Mary A. Grimes Cromwell Lathrop—William and Clarissa’s eldest daughter. Through Mary and her younger sister Cecelia of San Francisco, the family legacy endured bi-coastally through the next generation, supported by an oral history that eventually reached me.

Regina E. Mason, a descendant of William Grimes, is co-editor of Life of William Grimes, the Runaway Slave (Oxford University Press, 2008) and the subject of the documentary Gina’s Journey the Search for William Grimes.

Explore!

Grating the Nutmeg Episode 127: Telling Your Family Story with Jill Marie Snyder and Orice Jenkins

Are you your family’s historian? The one that listens to all the elders’ stories or digs into that big box of old family photographs? Here from two family historians in this episode of Grating the Nutmeg.

GO TO NEXT STORY

GO BACK TO WINTER 21-22 CONTENTS