By Walter W. Woodward

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Summer 2022

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

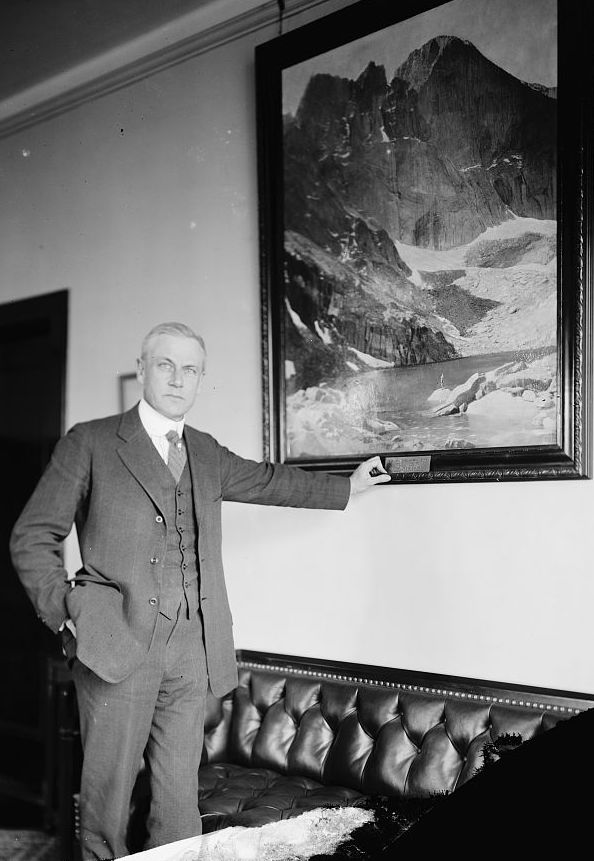

Stephen Tyng Mather was born and educated in California, but he considered the ancestral 1778 Mather homestead in Darien his true home. He summered there as a boy, inherited the home from his father in 1906, and was buried on the grounds in 1932, according to the Mather Homestead website (matherhomestead.org).

In my reading of his life story, Mather’s Connecticut roots gave him a love for America’s origins and history, while his western upbringing instilled a similar passion for the country’s extraordinary natural landscapes. After achieving success with the Thorkildsen-Mather Borax Company founded in California in 1898, Mather left borax mining and devoted his later life to preserving the country’s historic and natural treasures. His tireless efforts led to the creation of the United States National Park Service, of which he became the first director.

A 1905 Sierra Club-sponsored climb up 14,500-foot Mount Whitney in California left him a committed wilderness advocate. As Kate Siber notes in “The Visionaries” (National Parks Conservation Association, npca.org), he had been further influenced by a 1912 meeting with the aged preservationist John Muir. Muir had decried the damage lumbering and mining had inflicted on America’s wilderness, devastation Mather witnessed on trips to the Sequoia and Yosemite national parks two years later.

America’s national parks, of which there were then 13, were under siege. Robert Shankland in Steve Mather of the National Parks (Knopf, 1954) described how each was treated as a separate entity, woefully underfunded, managed by army personnel or political appointees, and under constant attack from members of Congress. “A good many Congressmen,” he wrote, thought the government should not be in “ ‘the show business’ and ‘the raising of wild animals’.” Possessed of what Shankland called “a striking alloy of drive and amiability,” Mather embarked on a personal mission to save the national parks.

After leveraging connections to secure a post in 1915 as assistant secretary to the U.S. Department of the Interior, Mather lobbied tirelessly for the parks. He paced the corridors of power in Washington, D.C. and traveled more than 30,000 miles in one year promoting the parks’ importance. An expedition he organized in July 1915 attracted 19 politicians, the editor of National Geographic, business leaders, and other notable influencers. The press promptly dubbed it “The Mather Mountain Party.” By car, foot, and horseback, the expedition toured Yosemite and Sequoia national parks, where Mather won converts by personally paying for expensive dinners catered on the trail, joking enthusiastically about waterfalls as free showers (and offering demonstrations), and, more seriously, showing the need for increased park stewardship, funding, and protection. “If he was out to make a convert,” Sierra Club President Francis Farquhar said of Mather (quoted in “The Visionaries,”), “the subject never knew what hit him.”

Mather’s work won victory in 1916 for legislation creating the National Park Service. He was appointed the first director. As Kiki Leigh Rydell and Mary Shivers Culpin note in Managing the Matchless Wonders: A History of Administrative Development in Yellowstone National Park 1872 – 1965 (National Park Service), Mather and his assistant Horace Albright proved naturals at publicizing America’s national parks’ benefits, creating a professional organization (including inventing the Park Ranger) to administer them, and building public appreciation for preserving the nation’s natural beauty and history. Mather served as director until 1929, when a stroke led to his resignation. He died January 22, 1930 and is buried at the Mather family homestead, a National Historic Landmark.

Walter W. Woodward will retire as the Connecticut state historian on June 30, 2022. Listen to his podcasts at Gratingthenutmeg.libsyn.com.

Explore!

Read more about Connecticut’s historic landscape & environmental history and other Notable Connecticans on our TOPICS pages

“Connecticut’s Forest and Park Pioneers,” Winter 2016-2017

GO TO NEXT STORY

GO BACK TO SUMMER 2022 CONTENTS