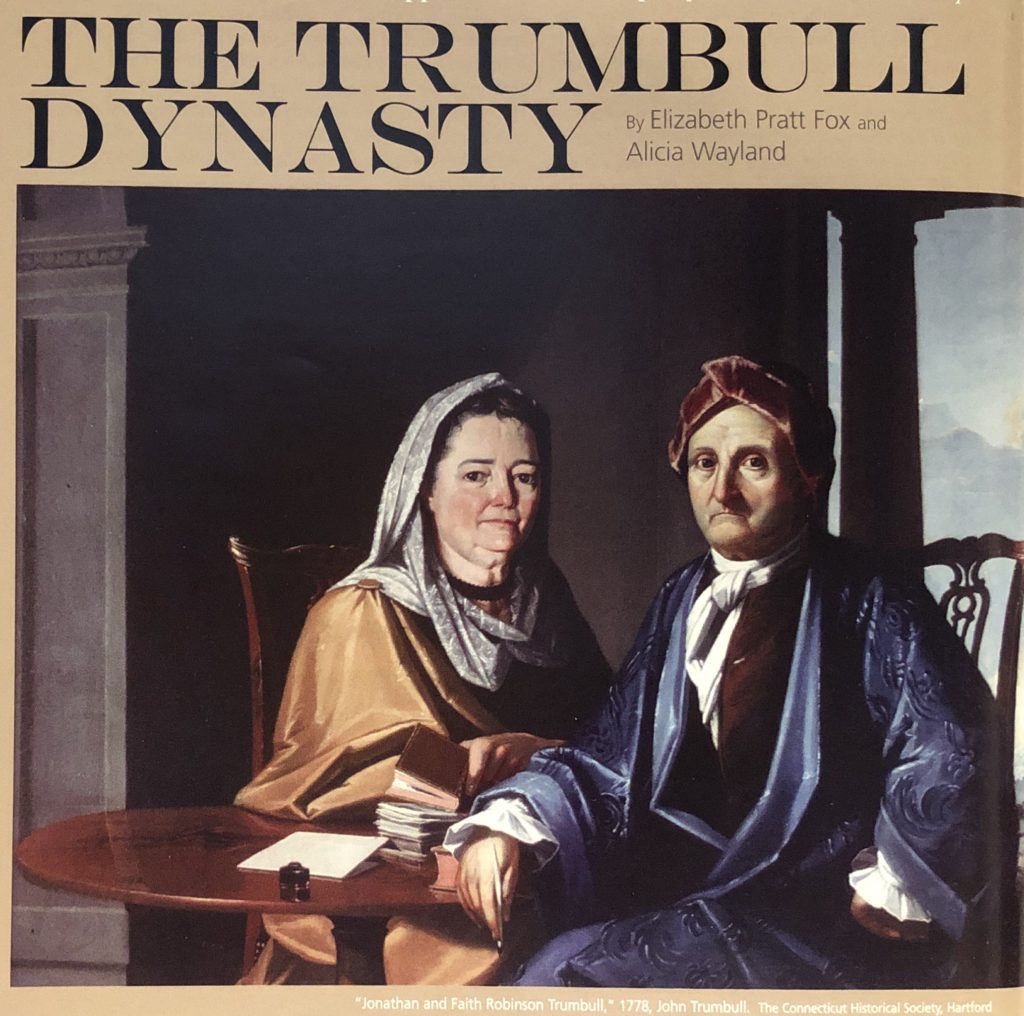

John Trumbull, “Jonathan and Faith Robinson Trumbull,” 1778. Connecticut Historical

Society Museum, Hartford

By Elizabeth Pratt Fox and Alicia Wayland

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Fall 2010

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

Three hundred years after his birth in Lebanon, Jonathan Trumbull, Sr. is best known as the state’s civilian commander in chief during the Revolutionary War and for his role in provisioning the starving troops at Valley Forge and Morristown. A friend of George Washington, he was the only colonial governor to support the War for Independence and to serve as the governor of a state, which he did from 1769 to 1784. Today the name Trumbull is among Connecticut’s most prominent place names: Streets, a town, a college at Yale University, and many other sites have adopted the family surname.

Jonathan Trumbull’s life would appear to be an exemplary American success story. Serving in elected office, though, was not Trumbull’s only activity. For most of his life he was a storekeeper and merchant. Trumbull took great pride in his roles as a merchant, local and state leader, and patriarch of one of Connecticut’s great family dynasties. But his remarkable achievements in the public realm weren’t matched in his business endeavors. Trumbull struggled to keep afloat financially, and, as his political responsibilities grew, so did the challenge to ward off bankruptcy.

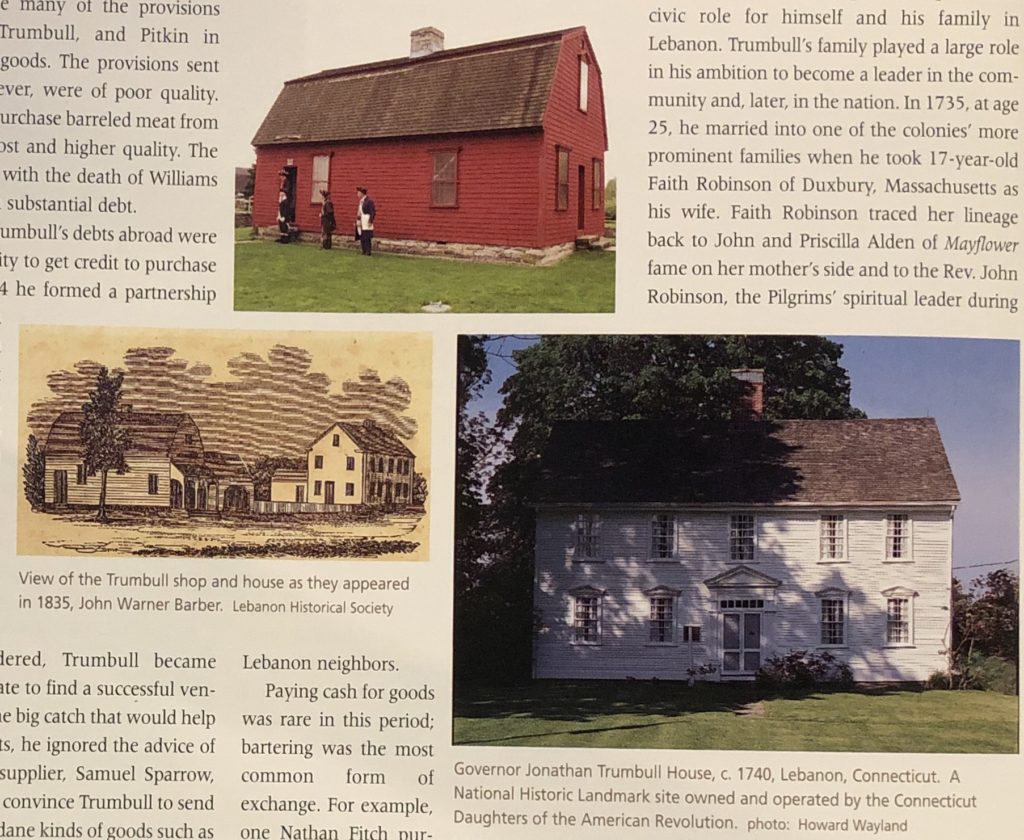

Trumbull’s mercantile career was slowing to a trickle just as he began to devote his time and the building that housed his shop to the revolutionary cause. By 1772 he had bonded his house and his furnishings to ward off his creditors, and his shop was probably low, if not empty, of stock. When hostilities began in April 1775, Trumbull turned his store into his headquarters, where more than 500 of the Council of Safety’s 1,102 meetings were held from 1775 to 1783. It was in this building that the state’s defense was planned and where Trumbull’s mercantile connections enabled him to gather the men, weapons, and provisions needed to continue the war effort to ultimate victory. It had achieved the iconic status of Boston’s Faneuil Hall when early 19th-century writers such as John Warner Barber referred to it as the “War Office,” and the Connecticut Sons of the American Revolution retained that name when, as new owners they turned the building into a museum in 1891.

The story begins in 1705 when farmer Joseph Trumble (the family changed the spelling in 1766) moved from Simsbury to the developing town of Lebanon. Joseph was described by his grandson, the artist John Trumbull, as a “respectable, strong minded but uneducated farmer.” He raised cattle, which he drove to Boston and traded for goods to sell to his fellow townspeople. This Trumble, Jonathan’s father, built a good life in town.

Jonathan was born in October 12, 1710, five years after his older brother, another Joseph. Both sons were expected to follow in their father’s footsteps to become prominent men in the community. Joseph Jr. joined his father’s trading business, Trumble and Son. In 1723, at age 13, Jonathan was sent to Harvard to study for the ministry. After graduation he returned to Lebanon to study theology with Rev. Solomon Williams and then returned to Harvard in 1730 for a master’s degree in that subject. At the same time, he remained involved in the family business, and in 1731 he formed a partnership with his brother and represented the firm in Boston. He might have also been an investor, along with his father and brother in the brigantine Lebanon that was built for trade in the West Indies. Tragically, Joseph Jr. and the Lebanon were lost at sea on the way to Barbados in 1732. As the oldest surviving son, Jonathan would now be responsible for maintaining the Trumbull legacy in Lebanon. (Jonathan’s younger brother David, born in 1723, drowned in 1740, leaving Jonathan as the sole male heir.)

With the death of his older brother, Jonathan quickly became an integral partner in Trumble and Son, and within four years he headed the firm. From 1735 forward, the business ledgers (now in the Trumbull Papers at the Connecticut Historical Society) have Jonathan’s name on the cover. Jonathan continued his father’s business of trade in both livestock and packed meat. From 1731 until 1749 he purchased cattle from neighboring farmers; every fall, as soon as he had about forty head, he would send the herds to market in Boston. Jonathan also expanded into the hog trade. Before the development of refrigeration in the 19th century, salting meat, with either dry salt or brine, was the most common method for preserving meat. The salted meat was packed in barrels for shipment, and, if packed well, would keep for months and even years. As soon as the cattle season ended, Trumbull would purchase hogs and have them slaughtered and the meat packed in Lebanon for transport to the port cities of Boston, Newport, Norwich, and new London. Trumbull became the largest meatpacker in colonial Connecticut. He traded livestock and barreled pork for sundry goods that he sold from his shop in Lebanon.

top: Trumbull shop, now the War Office historic site, Sons of the American Revolution. bottom left: View of the Trumbull shop and house by John Warner Barber, 1835. Lebanon Historical Society. bottom right: Governor Jonathan Trumbull House, built c. 1740, Lebanon, is a National Historic Landmark and museum operated by the Daughters of the American Revolution. photo: Howard Wayland.

In 1749 Trumbull formed a partnership with Elisha Williams (1694-1755) of Wethersfield and William Pitkin (1696-1769) of Hartford to establish direct trade with England. Both Williams and Pitkin were well-established merchants in the Connecticut River Valley. While in London on business in 1750, Williams purchased one-half of an interest in the ship the Sarah, which was used to transport goods between England and Spain. Williams planned to bring the ship to Connecticut and load it with goods to be sold in England, Ireland, the Straits of Gibraltar, and Lisbon. On its first trip to Connecticut, the Sarah met with bad weather, and the voyage took more than nine months, including a winter in Antigua. Williams’s visions of international trade were beginning to look nightmarish. While the partners dreamed of future profits and waited for the Sarah to arrive, they eyed the trading ports of Nantucket and Halifax, Nova Scotia. In Nantucket, they traded foodstuffs such as beef, pork, butter, and hog’s fat from Connecticut for whale oil, which they then sold in Lebanon.

In 1752 Trumbull and his partners also opened up trade with Captain Joshua Mauger, a merchant in Halifax. Mauger obtained a contract for provisions for the Ryal Navy and began to purchase many of the provisions from Williams, Trumbull, and Pitkin in exchange for dry goods. The provisions sent by the firm, however, were of poor quality. Mauger began to purchase barreled meat from Ireland at lower cost and higher quality. The partnership ended with the death of Williams in 1755 — and with substantial debt.

By the 1760s, Trumbull’s debts abroad were hampering his ability to get credit to purchase goods, and in 1764 he formed a partnership with Eleazar Fitch (1726-1796), a wealthy merchant from Windham. But within two years, Fitch pulled out of the partnership because he was losing money, leaving Trumbull to search for new capital. As the partnership foundered, Trumbull became increasingly desperate to find a successful venture. In search of the big catch that would help him pay off his debts, he ignored the advice of his major London supplier, Samuel Sparrow, who tried in vain to convince Trumbull to send to London the mundane kind of goods such as potash for pearl ash that were in demand there.

Throughout this period of partnerships, Trumbull continued to sell from his small shop in Lebanon. The shop was located on a corner lot on the road to Colchester, a short distance from its present site. In this small building, Trumbull conducted his very active business, trading livestock and selling local and imported goods for retail. Trumbull carried a wide variety of goods that appealed to the local people: gloves, hanks of silk, rum, scissors, nails, chamber pots, spices, sugar, felt hats, knives, dried fruit, tea, combs, spectacles, textiles, and gun powder. Trumbull’s ledgers also record that he was very generous in extending credit to his Lebanon neighbors.

Paying cash for goods was rare in this period; bartering was the most common form of exchange. For example, one Nathan Fitch purchased a chamber pot along with a worsted cap, rum, nails, pepper, hank of silk, ginger, shalom (fabric), sugar, a broom, and a handkerchief. He paid Trumbull by carting goods from Norwich and by selling him cheese, beef, and hides. In 1739, Josiah Dewey purchased a pair of spectacles, women’s gloves, mohair, buttons, and an iron kettle. He paid with butter, a goose, cheese, beeswax, and a grey fox.

Still, the devaluing of colonial notes in this period affected Trumbull, who had large debts owed to him in a currency whose value was decreasing. Trumbull’s financial problems grew as he continued to receive credit for imported goods while he failed to collect from those in debt to him.

As his mercantile business was failing, Trumbull continued to pursue a prominent civil role for himself and his family in Lebanon. Trumbull’s family played a large role in his ambition to become a leader in the community and, later, in the nation. In 1735, at age 25, he married into one of the colonies’ more prominent families when he took 17-year-old Faith Robinson of Duxbury, Massachusetts as his wife. Faith Robinson traced her lineage back to John and Priscilla Alden of Mayflower fame on her mother’s side and to the Rev. John Robinson, the Pilgrims’ spiritual leader during their sojourn in Holland, on her father’s side. The Trumbull family quickly grew with the birth of four sons and two daughters. In addition to his six children, Trumbull’s sister Hannah’s orphaned son also lived with the family.

The Trumbulls also owned at least four enslaved Africans. Bristol, who had originally belonged to Trumbull’s father Joseph, died sometime before 1764. Flora was purchased by Jonathan in 1736. Hector, who was married to Flora in 1743, became of servant of Jonathan from before 1746 and was free by 1753. Trumbull also inherited his father’s slave Grace. She is listed in Joseph’s distribution papers as “one mulatto Girl, name Grace, near 14 years old.” She married in 1760, divorced, and returned to live with the Trumbulls as a free servant until her death in 1774. Her son Isaac also lived in the house.

All of Trumbull’s sons except David were educated at Harvard, and all four sons played important toles during the Revolution. Three of his sons, Joseph, Jonathan, and David, were involved in the family business. Jonathan would also enter politics and, like his father before him, would serve as governor, from 1797 to 1809. John, the youngest Trumbull, is perhaps best known today for his paintings of key events in the founding of the country [See John Trumbull: Picturing the Birth of a Nation,” Winter 2006/2007]. Trumbull’s daughters, Faith and Mary, were both educated in Boston and were expected to — and did — enter into advantageous marriages. Faith married Colonel Jedediah Huntington of Norwich, [see their tall clock, page 27]and Mary married William Williams, a Lebanon merchant, delegate to the Continental Congress, and a signer of the Declaration of Independence.

John Trumbull, “Jonathan Trumbull, Jr., Eunice Trumbull, and Faith Trumbull,” 1777. Yale University Art Gallery

Trumbull was involved in the intellectual life of the town as one of the founders (in January 1738 of 1739) of the Philogrammatican Society, one of the first non-academic libraries in America, and also a founder in 1743 of the Tisdale School, a private school in town that attracted students from all the colonies and the West Indies. He also studied religion and was an active member of the Congregational church. He particularly enjoyed the lectures in the town center’s meetinghouse, where the First Society held its services. In 1753 he gave a pewter communion flagon to the church. As many did in eastern Connecticut, he took a great interest in the revival movement known as the Great Awakening.

Trumbull joined several prominent men in eastern Connecticut in invoking the sea-to-sea clause in the Connecticut charter to justify their claims to lands in northern Pennsylvania along the Susquehanna River. Trumbull also owned a grist mill, a malt house and brewery, and a fulling mill, which he rented out. His large farm cost little to operate because labor was provided by people working off their debts to him as well as by his own slaves and servants. These local enterprises provided Trumbull with the income to support his family — income that never materialized from his grandiose schemes to become a trans-Atlantic trader.

Despite his difficulties in international trade, Trumbull’s lifestyle was that of a successful man. His clothes were made for him in Boston, and his carriage was one of the best in Connecticut. His home was the finest house in Lebanon at the time and was the center for gracious entertainment. The Trumbulls often hosted prominent people both for tea and for meals, and they furnished their home accordingly. In addition to fine furniture, ceramics, and silver, the Trumbull home was decorated with his daughter Faith’s fine needlework landscapes, textiles, and a double portrait of Trumbull and his wife painted by their son John.

By the late 1750s Trumbull’s creditors became concerned about his London debts. Trumbull was floating large debt in hopes that one of his ventures would pay off. In 1759 his Boston supplier, Lan and Booth, wrote to Trumbull that they were fearful of his debt and “Disappointment in this point often gives us much uneasiness…” By 1763, at the same time Trumbull was facing bankruptcy, his sons Joseph and Jonathan joined the firm. Joseph was sent to London to secure more credit and then to Norwich to set up the wharf from which the firm Trumbull, Fitch and Trumbull would sail its ships. He also built a malt house there. The British were passing the Sugar Act (1764) and the Stamp Act (1765), both of which endangered the colonies’ economy. Trumbull’s London suppliers, fearful of not collecting their debts, threatened to sue him in court. Soon thereafter, his Boston creditors also threatened to sue, which would have been a public humiliation.

If the Trumbulls were to fend off their creditors they needed to raise cash quickly. To that end, in 1766 Jonathan and three of his sons gathered provisions in Connecticut and whale oil in Nantucket to place on two of their ships and on another owned by Nathaniel Shaw of New London. A new vessel, the snow Neptune, built at the Trumbull shipyard in East Haddam, was loaded with oil from Nantucket and sent to London. The ship leaked badly only four days out of port. The crew was rescued by a passing vessel, and the ship sank shortly thereafter. The Trumbulls also provided foodstuffs that were part of the cargo on the brigantine Lucretia, owned by Nathaniel Shaw. The Lucretia arrived in Martinique, but the Trumbull share of the cargo sale is not known. The ship Dublin, also built in East Haddam, was sent to Ireland with flaxseed, oak bark, and oak planks, but the cargo was of such poor quality that the Trumbull agent in Newry had trouble selling it. The agent could not sell the ship, either, because the price was too high, so he sent it on to Liverpool. The Dublin was never heard from again and is presumed to have sunk.

Though Trumbull did have some minor successes in trade, by 1766 he was insolvent. Rather than declare formal bankruptcy, Trumbull entered into an agreement with each of his creditors. At the same time he continued to extend credit to those that could not repay their debt. He could not collect the £10,000 owed to him, and he would not tolerate the humiliation of public bankruptcy. His choice was to continue to seek a way toward solvency, to transfer his properties to his sons to protect them from his creditors, and to intimidate his creditors.

Jonathan died insolvent in 1785. His son David drew up a document in 1786 for the probate court documenting Trumbull’s debts at the time of his death. His creditors included Lane and Booth, a London supplier of goods for his shop to whom he had bonded his dwelling house, property, and furnishings in 1772. Stephen Apthorp, son of the late Charles Apthorp of Boston and the owner of a mercantile house in Bristol, England, was also listed, as was a Mr. Pitts, probably John Pitts of Boston, and the Floyds of Long Island, including William Floyd, a member of the Continental Congress and the First Congress. Trumbull’s son David was owed more than £3,000. Trumbull owed a total of £15,420, and his estate of £6,000 had been mortgaged to his creditors. He may have kept the family name out of bankruptcy, but upon his death he could not escape public knowledge of his debts.

Trumbull’s business failures are stark contrast to the public career of the man who led Connecticut’s extraordinary response to the patriot cause during the Revolutionary War. For eight long years, the day-to-day operations of the war effort fell on his shoulders as the state’s commander in chief. Trumbull’s long commercial career culminated in a unique logistical knowledge of the people and resources of the state, enabling him to respond to the pleas for provisions from General George Washington for the Continental Army and the French Army. Perhaps none of these responses had more impact than the cattle drives that saved the starving soldiers at Valley Forge and Morristown. Under his Herculean leadership, the state produced the outpouring of men, armaments, and provisions that earned Connecticut the nickname “The Provisions State.”

Elizabeth Pratt Fox is a museum consultant and was the guest curator of the exhibition Jonathan Trumbull, A Merchant Struggling for Success at the Lebanon Historical Society.

Alicia Wayland is the municipal historical for the town of Lebanon and writes frequently on Lebanon topics.

Note: This article is based on new research and several research papers and publications used to develop the Lebanon Historical Society’s new exhibition Jonathan Trumbull, A Merchant Struggling for Success. The authors cite especially David M. Roth, “Jonathan Trumbull, 1701-1785: Connecticut’s Puritan Patriot,” unpublished dissertation, Clark University, 1971, and Glenn Weaver, Jonathan Trumbull: Connecticut’s Merchant Magistrate (1710-1785) (Hartford: The Connecticut Historical Society, 1956.)

Explore

Explore more Notable Connecticans on our TOPICS page.

Visit

Lebanon Historical Society Museum & Visitors Center

856 Trumbull High Way, Lebanon

HistoryofLebanon.org

Link to an illustration of the Trumbull Family Tree