(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Winter 2006/2007

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

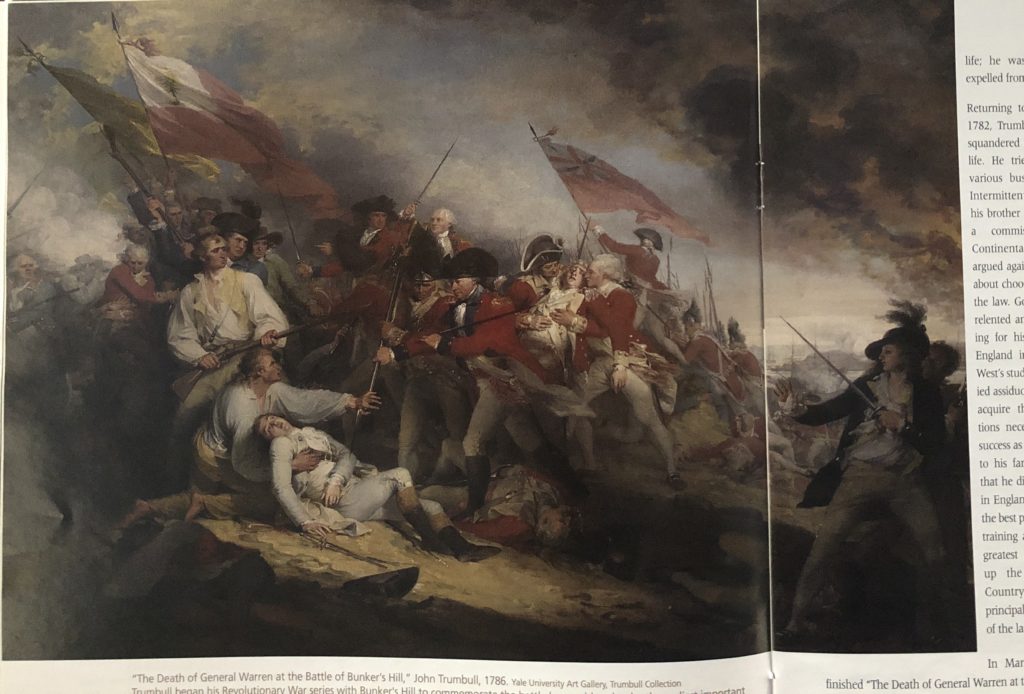

The year 2006 marks the 250th anniversary of the birth of John Trumbull, the preeminent artist of the American Revolution.

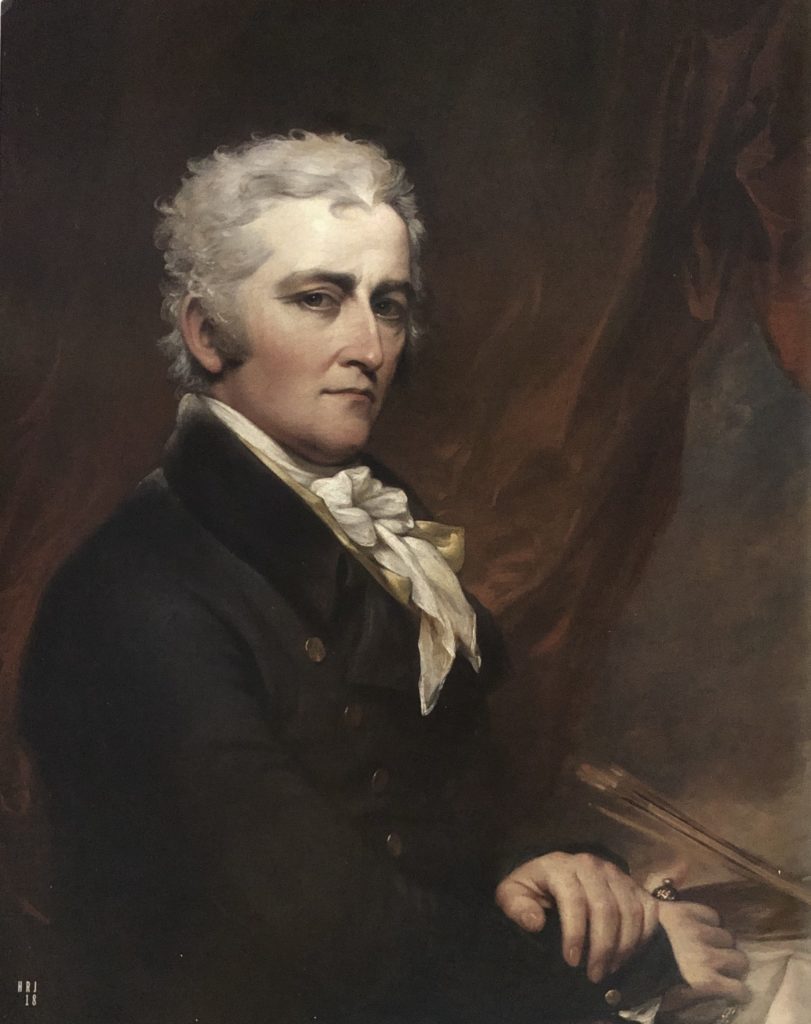

In a letter to Thomas Jefferson in 1816, native Connecticut patriot and painter John Trumbull (1756-1843) explained why he was uniquely qualified to record on canvas the birth of the nation: “Some superiority also arose from my having borne personally a humble part in the great events I was to describe.” None of his contemporaries possessed this advantage, Trumbull wrote, “and no one can come after me to divide the honor of truth and authenticity.” Indeed, some years later, more than four decades after the war’s end, Trumbull described himself as “the Oldest Surviving American officer of the Army of the Revolution.” Never shy about promoting himself, Trumbull, with the help of Jefferson and John Adams, prevailed on Congress in 1817 to award him a major commission to paint four monumental canvases for the rotunda of the Capitol in Washington.

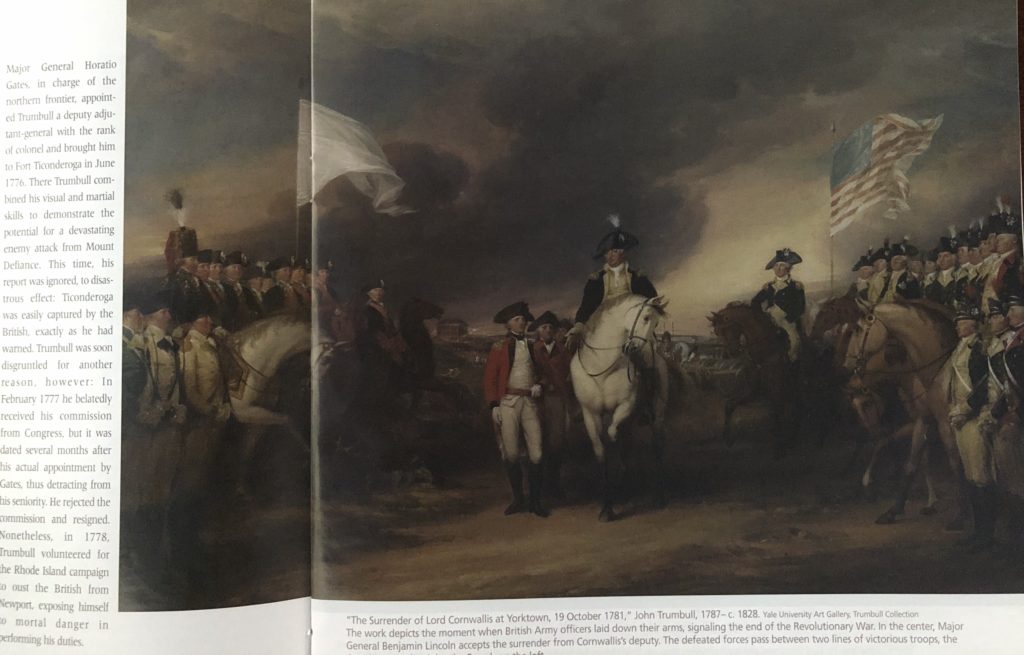

In his autobiography, published in 1841 and the first by an American artist, Trumbull described his meeting with President James Madison when they sat down to choose the subjects for this, the artist’s most important commission. They settled on the signing of the Declaration of Independence and the resignation of George Washington for the two civil subjects. Flush with victory at the end of the Revolution, Washington might have become a dictator; instead, he embodied the principle that in a free republic the military must always be subordinate to civil authority. “I have thought that one of the highest moral lessons ever given to the world, was that presented by the conduct of the commander-in-chief, in resigning his power and commission as he did,” Trumbull told Madison. For the other two paintings, Trumbull argued successfully that the American victories at Saratoga and Yorktown were the two most crucial military events of the Revolution. “We had, in the course of the Revolution, made prisoners of two entire armies, a circumstance almost without a parallel.”

Soldier and Artist of the American Revolution

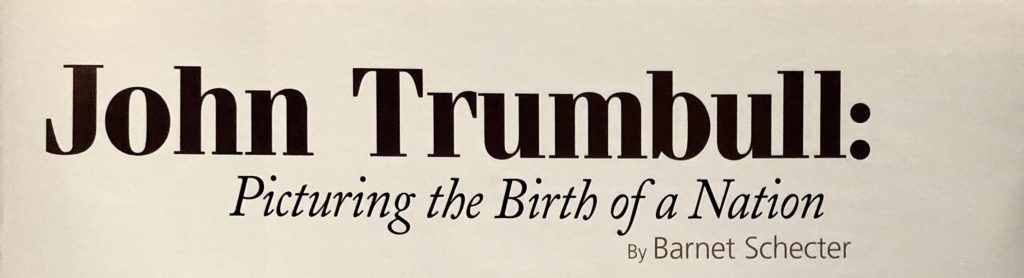

John Trumbull’s iconic paintings of scenes from the American Revolution, including “The Death of General Warren at the Battle of Bunker’s Hill,” now at the Yale University Art Gallery, and the canvases for the Capitol, are the primary images through which the public envisions the war and its heroes. Keenly aware that the Revolutionary generation was fast dying off, Trumbull traveled far and wide to create portraits of the key participants and insert them into his paintings.

Trumbull’s achievements are all the more remarkable considering that the artist was blinded in one eye at age five when he fell down a flight of stairs. Knocked unconscious, he had a large bruise over his left eye, but “no other evil was suspected, until several years after, when happening to shut the right eye, I found I could not see,” Trumbull recalled in his autobiography. “To this day I have never been able to read a single word with the left eye alone.”

John Trumbull, “The Death of General Warren at the Battle of Bunker’s Hill,” 1786. Yale University Art Gallery, Trumbull Collection

Trumbull’s life bridged the Revolution and early republic to the age of Andrew Jackson and its celebration of the common man. He was an artist without an inherited fortune or steady patronage, caught between the worlds of European culture and American commerce while buffeted by the wars and tumultuous political developments of the age. A Federalist, not a Democrat, and a proud, aristocratic gentleman in his bearing and self-conception (aspects of his personal conduct notwithstanding), Trumbull in the 1830s decried the “leveling spirit of the age.” Indeed, his visual record of the Revolution focuses on the noble deeds of the elite, not the proletarian aspects of the struggle. Ultimately, financial success eluded him, but he attained a greater goal: fostering the fine arts in the new nation, while creating enduring works in a distinctly American idiom.

The painter, soldier, diplomat, and author was born in Lebanon, Connecticut, on June 6, 1756, the youngest of six children of Jonathan Trumbull, then a representative to the Connecticut General Assembly and later governor of the State of Connecticut, and his wife Faith Robinson. His father, Jonathan Trumbull, was the only colonial governor to become an American patriot. In Lebanon, the elder Trumbull turned his store into a war office, where he held strategy sessions. He made Connecticut “the Provisions State,” supplying the Continental and French forces with food, uniforms, and camp equipment. It was on Connecticut soil that George Washington and the French general comte de Rochambeau first met, beginning the relationship between the allies that led to the 600-mile march to Yorktown, Virginia, the military campaign that would culminate in a decisive, pivotal victory of the Franco-American forces over the British on October 19, 1781.

But that was still many years away. The young John excelled in school, especially at languages, reading Greek at age six. His irrepressible artistic bent also displayed itself early, as he sketched on the smooth wooden floors at home. In 1772, at 16, he hoped to study painting with John Singleton Copley in Boston, but at the behest of his father he entered Harvard, as a junior, instead. There he taught himself about art from books and from paintings owned by the college. Trumbull graduated in 1773, on the eve of the American Revolution.

After the Boston Tea Party in December 1773 and the resulting British crackdown on the city, John returned to Lebanon and formed a military company from the village, he recalled in his autobiography, wherein “we taught each other, to use the musket and to march.” In 1775, with the British bottled up in Boston after the skirmishes at Lexington and Concord, Trumbull was stationed outside the city, at Roxbury, as an adjutant of the First Regiment of Connecticut. He performed as soldier and artist simultaneously, crawling through the tall grass in front of the British lines at Boston to draw a map and sketch of the enemy position. His skill and courage won him the notice of General Washington and appointment as one of his aides.

Major General Horatio Gates, in charge of the northern frontier, appointed Trumbull a deputy adjutant-general with the rank of colonel and brought him to Fort Ticonderoga in June 1776. There Trumbull combined his visual and martial skills to demonstrate the potential for a devastating enemy attack from Mount Defiance. This time, his report was ignored, to disastrous effect: Ticonderoga was easily captured by the British, exactly as he had warned. Trumbull was soon disgruntled for another reason, however: In February 1777 he belatedly received his commission from Congress, but it was dated several months after his actual appointment by Gates, thus detracting from his seniority. He rejected the commission and resigned. Nonetheless, in 1778, Trumbull volunteered for the Rhode Island campaign to oust the British from Newport, exposing himself to mortal danger in performing his duties.

An Apprenticeship in London

Newport remained in British hands, and Trumbull returned to Lebanon, where he continued drawing and painting on his own. Unmoved by his father’s advice to study law, Trumbull went to Boston to try once again to study with artist John Singleton Copley. But Copley was in Europe, so Trumbull stayed on in Boston to study from copies of European masters that he found in his rented studio. The following year, after a disappointing stint in his brothers’ tea and rum business, he decided to pursue his artistic training in England.

John Trumbull, “The Surrender of Lord Cornwallis at Yorktown, 19 October 1781.” Yale University Art Gallery, Trumbull Collection

In 1780 he began studying with the American painter Benjamin West in his London studio. Trumbull got along well with fellow student Gilbert Stuart, later famous for his portraits of George Washington. Trumbull’s apprenticeship was abruptly curtailed when the British government arrested him for treason and imprisoned him for almost eight months. The pretext for his arrest was anti-British views expressed in his letters home, but Trumbull was convinced he was jailed in retribution for the execution of Major John Andre, a British agent in the plot to capture West Point with the help of Benedict Arnold. Influential friends appealed to the king, who spared Trumbull’s life; he was released and expelled from England.

Returning to New York in 1782, Trumbull felt he had squandered two years of his life. He tried his hand at various business ventures. Intermittently, he helped his brother David, who was a commissary of the Continental army, and argued again with his father about choosing the arts over the law. Governor Trumbull relented and gave his blessing for his son’s return to England in 1784. Back in West’s studio, Trumbull studied assiduously and began to acquire the social connections necessary to financial success as a painter. In letters to his family, he explained that he did not feel at home in England but considered it the best place to complete his training and prepare for his greatest ambition, “to take up the History of Our Country, and paint the principal Events particularly of the late War.”

In March 1786, Trumbull finished “The Death of General Warren at the Battle of Bunker’s Hill,” which West declared “the best picture of a modern battle that has been painted.” Trumbull also completed “The Death of General Montgomery in the Attack on Quebec” and began painting three other battles of the Revolution. That summer, Trumbull went to Paris, where the American minister, Thomas Jefferson, had offered to be his host. Jefferson introduced Trumbull to the great artists of the day, to their wealthy patrons, and to their stunning collections of paintings by the Old Masters.

The connoisseurs in turn were favorably impressed with Trumbull’s paintings, and Jefferson commented that “his natural talents for this art seem almost unparalleled.” Trumbull began sketching out a scene depicting the signing of The Declaration of Independence and drew on Jefferson’s first-hand knowledge of the event. Trumbull also traveled through Germany and the Low Countries, keeping copious notes about everything he saw. In November he returned to London, where he began painting “The Declaration of Independence.” A year later he returned to Paris to paint Jefferson’s portrait for the final canvas. He had also brought “The Surrender of Lord Cornwallis at Yorktown” to insert portraits of the French officers into this painting.

Returning to London in 1788 and then to America in 1789, Trumbull offered subscriptions for sale of prints based on his works “Bunker’s Hill” and “Quebec.” The practice of creating and selling editions of engravings promised an artist income beyond the sale of the single, original painting. Trumbull pinned his hopes for long-term financial stability on such prints, but the promise was never fulfilled. From 1789 to 1793 he traveled throughout the United States making portraits of living participants for his history paintings. The American public, however, was distracted by politics abroad—the French Revolution, the war between Britain and France—and had little interest in art. Without patronage, Trumbull began to give up on his grand ambition of depicting the Revolution.

In 1794 he became Chief Justice John Jay’s secretary on the Jay Treaty Commission in London. The following year he went to Paris on further diplomatic business and stayed on for another year, buying up valuable paintings at fire-sale prices from ruined French aristocratic families and selling them in England; he also speculated in the tobacco and brandy trade. Having gotten out of debt, and still counting on the sale of his engravings, Trumbull again turned his thoughts to the project of documenting the American Revolution.

In 1797 Trumbull returned to France on further diplomatic service involving the Jay Treaty and was drawn into the intrigues of the French foreign minister, Talleyrand, who tried to extort information about the treaty from him by denying him a passport to leave the country. Trumbull refused to cooperate and, with the help of the painter Jacques-Louis David, managed to obtain permission from the French government and return to England in 1798. Trumbull’s engravings, including “Bunker’s Hill” and “Quebec,” had been published by the time he began painting again in 1800.

On a trip to America some eight years earlier, an affair with Temperance Ray, a servant in his brother’s house, had produced a son out of wedlock named John Trumbull Ray, who was born in 1792. While the paternity was uncertain, “the Business was ill-managed, became public,” Trumbull recalled in a letter to James Wadsworth; the artist took responsibility for the boy’s support and education. In 1800, at 44 years old, Trumbull shocked his friends and family again by marrying a very beautiful 26-year-old Englishwoman, Sara Hope Harvey. Trumbull’s Yankee relatives were die-hard Anglophobes, and Sara’s family was also of a lower social class: she did not have the more refined education that had recently become fashionable for women.

In 1804, the Trumbulls settled in New York, and John focused on portrait painting. The post-Revolutionary mood of national unity had given way to bitter partisanship between the Federalists and the Democratic-Republicans leaving little interest in history painting. Trumbull was elected director of the New York (later, American) Academy of the Fine Arts, which was dedicated to “educating public taste,” and he received numerous public and private commissions. However, the 1807 Embargo Act, which cut off all foreign trade with U.S. ports, threatened the prosperity of his patrons. Elected vice president of the American Academy of Fine Arts, Trumbull nonetheless received fewer commissions. His eyesight failing, he went to England for medical care. Anti-American feeling ran high in the years leading up to the War of 1812, and Trumbull found few patrons in England, either. The couple was stranded by the outbreak of the war and did not return to New York until 1815. By then Trumbull was almost 60, and he found increased competition for commissions from contemporaries and younger painters.

Monumental Canvases for the Capitol Rotunda

In 1816-1817, plagued by money problems, Trumbull was successful in soliciting Thomas Jefferson and John Adams to get him a commission for the new Capitol in Washington. On January 27, 1817 Congress voted to commission four paintings of the most important events of the Revolution. Trumbull was awarded the first major commission by the U.S. government to an American painter.

John Trumbull, “The Declaration of Independence, 4 July 1776” (detail). Yales University Art Gallery, Trumbull Collection

Seven years later, Trumbull finally finished the four sprawling canvases, each measuring 18 feet by 12 feet to accommodate life-size figures. Tragically, at what should have been his moment of triumph, his beloved wife died—and his woes began to multiply. Trumbull’s leadership as president of the American Academy of Fine Arts came under attack, his opponents charging that he failed to hire instructors and denied students adequate access to the academy’s collection of casts from antique sculpture. The group’s prestige went into decline just as the rival National Academy of Design came into being in 1825. The following year, the Capitol Rotunda opened, but Trumbull received no further commissions to adorn four remaining niches, which were eventually filled by the work of others.

In 1830, recovering from cholera and saddled with debt, Trumbull offered to donate the bulk of his paintings to Yale College—not his alma mater, but in his home state—in exchange for an annuity of $1,000 a year. Yale agreed and formed the Trumbull Gallery, the first college museum in the United States, which opened on October 25, 1832 with 55 pictures by the artist. A review in the Connecticut Journal declared, “Col. Trumbull has the hand and spirit of a painter… Altogether this Gallery must be considered the most interesting collection of pictures in the country. They are American.”

Trumbull died in 1843 at the age of 87 and was buried beneath his full-length portrait of George Washington and next to his wife, whose remains had been transferred to a crypt in the Trumbull Gallery when it opened. His epitaph reads: “To his country he gave his sword and his pencil.” Equally appropriate would have been the words of Abigail Adams, who wrote that Trumbull was the first painter “to immortalize by his pencil those great actions that gave birth to our nation. By this means he will not only secure his own fame, but transmit to posterity characters and actions which will command the admiration of future ages, and prevent the period which gave birth to them from ever passing away into the dark abyss of time.

Barnet Schecter is the author of The Battle for New York: The City at the Heart of the American Revolution and The Devil’s Own Work: The Civil War Draft Riots and the Fight to Reconstruct America. He is a contributing editor of the Encyclopedia of the American Revolution (3 vols.) Visit www.walkerbooks.com for more information.

Explore!

Read more stories about Connecticut’s art history on our TOPICS page.

“The Trumbull Dynasty,” Fall 2010