(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Winter 2019-2020

SUBSCRIBE/BUY THE ISSUE!

“If you build a better mousetrap, the world will beat a path to your door.” That statement, often attributed to Ralph Waldo Emerson, points to the notion of innovation—and, on the flip side, of obsolescence. But what about the original mousetrap? It “falls into disuse and becomes neglected,” as Connecticut’s Noah Webster defined the word “obsolete” in his 1839 An American Dictionary of the English Language. Typically, obsolescence occurs when there is a “decline in the competitiveness, usefulness or value” of an object, as the online BusinessDictionary.com defines obsolescence today. Alternatives become available on the market, and these “perform better or are cheaper or both.” Obsolescence also results from “changes in user preferences, requirements or styles.”

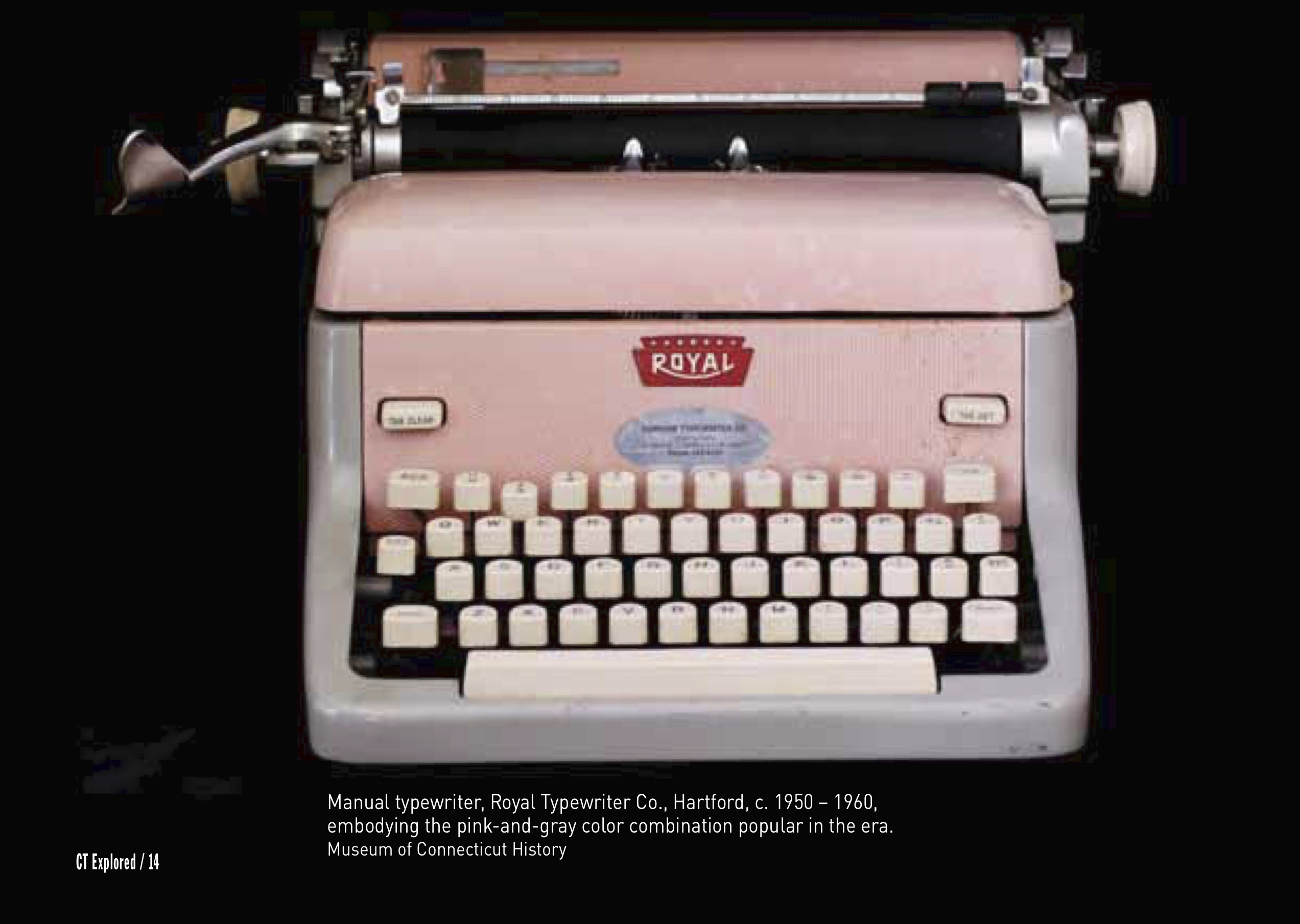

Typewriters offer a good illustration. A typewriter may still work well, but as it ages, parts break down and may be difficult to replace, and it becomes harder to find people with the skills needed to repair and keep the machine in working order. Typewriters also were susceptible to functional obsolescence. They were good at doing what they were designed to do: place letters and words on a single page of manually-loaded paper. Multiple copies could be made using carbon paper and mistakes corrected using correction paper and, later, correction fluid applied with a small brush. Personal computers eliminated the need for all of that by introducing monitors, “delete” keys, and printers.

Typewriters offer a good illustration. A typewriter may still work well, but as it ages, parts break down and may be difficult to replace, and it becomes harder to find people with the skills needed to repair and keep the machine in working order. Typewriters also were susceptible to functional obsolescence. They were good at doing what they were designed to do: place letters and words on a single page of manually-loaded paper. Multiple copies could be made using carbon paper and mistakes corrected using correction paper and, later, correction fluid applied with a small brush. Personal computers eliminated the need for all of that by introducing monitors, “delete” keys, and printers.

By the 1940s the once-crowded field of Connecticut typewriter manufacturers—which had included Blickensderfer in Stamford, Yost in Bridgeport, the American Writing Machine Co. of Hartford, and Remington Noiseless in Middletown—consisted only of the two Hartford giants, Underwood and Royal, which then ranked among the world’s leading typewriter manufacturers. Between them, the two companies occupied more than a million square feet of floor space in their factories on Woodbine Street and New Park Avenue and employed thousands of Hartford-area residents.

Royal, acquired by Litton Industries in 1966, moved its manufacturing to England in 1972. Underwood was acquired by the Olivetti Corporation in 1959 and moved to a new manufacturing facility in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania in 1968. Hartford workers such as typewriter-key assemblers and final adjusters suddenly found their lives disrupted as their skill sets became as obsolete as the products they helped make. Their workplaces had become obsolete too, with urban, multi-story brick structures being supplanted by single-story factories in suburban industrial parks. The Underwood plant was torn down and replaced by two high-rise apartment buildings by the 1980s, and the vacant Royal factory was destroyed by a spectacular fire in 1992.

The process of “fall[ing]into disuse and becom[ing]neglected” sounds rather benign, perhaps ending happily only when “neglected” things find new homes in the collections of history museums. On the following pages, find a selection of Connecticut-used and mostly Connecticut-made products that are celebrated in local museum collections.

Spreading the Word

Connecticut-made products used to facilitate written communication range from wooden inkwells for use with steel pens and cursive writing to typewriters that mechanized the writing process and to personal computers that digitized it. The ADAM joined the ranks of home computers that were slowly replacing typewriters for personal use. Today personal computers offer the choice of several typefaces that imitate cursive writing, leading toward the potential obsolescence of handwriting.

ADAM home computer, Coleco Industries, West Hartford, 1983-1985. The ADAM was plagued by production problems and after Coleco failed to bring the innovative new computer to market in time for the holiday buying season in 1984, the product was discontinued in 1985. Museum of Connecticut History

Getting Somewhere

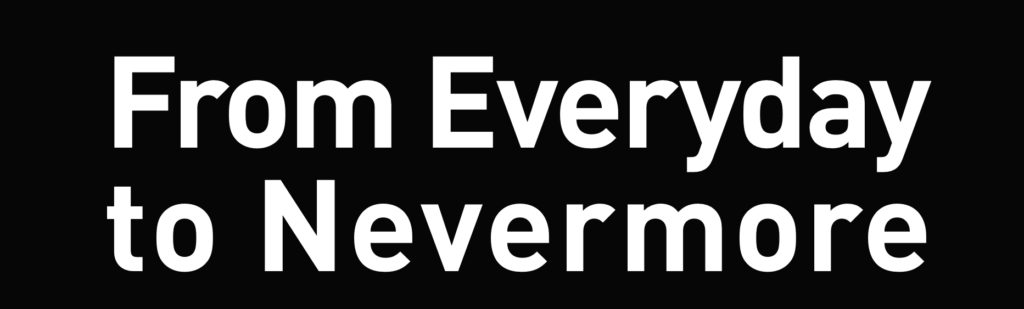

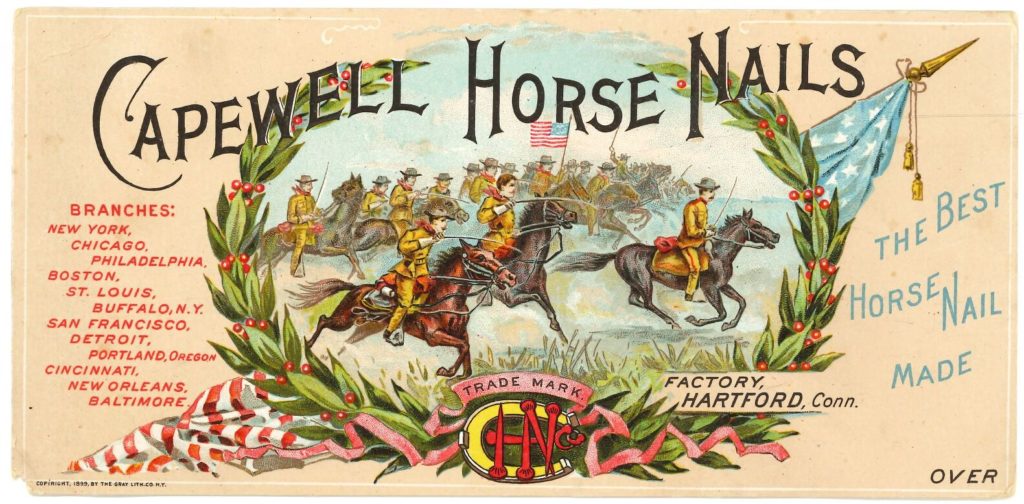

The evolution of transportation yielded its own set of once-critical products that later became obsolete. Founded in 1881, the Capewell Horse Nail Co. of Hartford came to dominate the American horse-nail industry. Using special machinery designed by George Capewell, the company produced nails for every conceivable use. But a decade later the invention of the “horseless carriage,” epitomized in Hartford by the Pope Manufacturing Co., signaled the decline in the use of horses in many every-day activities. With fewer horses to shoe, the demand for horse nails fell, and by the 1930s Capewell had diversified into the manufacture of saw blades and hand tools. The company’s large factory on Charter Oak Avenue closed in the 1980s and remained vacant for many years until its recent rehabilitation into an apartment building.

This 1899 trade card for Hartford-made Capewell Horse Nails implies the importance of quality horse nails with its depiction of Theodore Roosevelt and his Rough Riders. Museum of Connecticut History

Keeping it Fresh

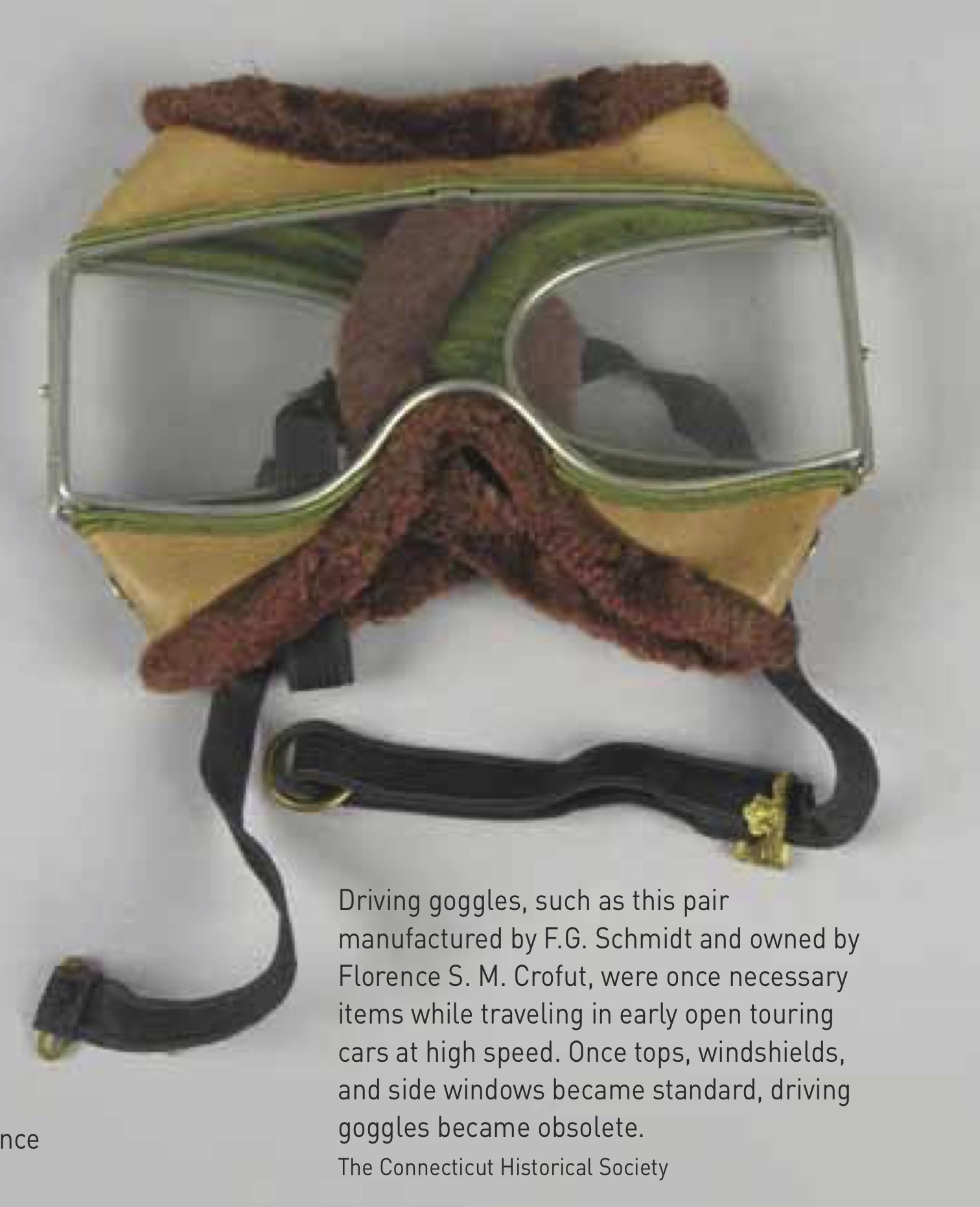

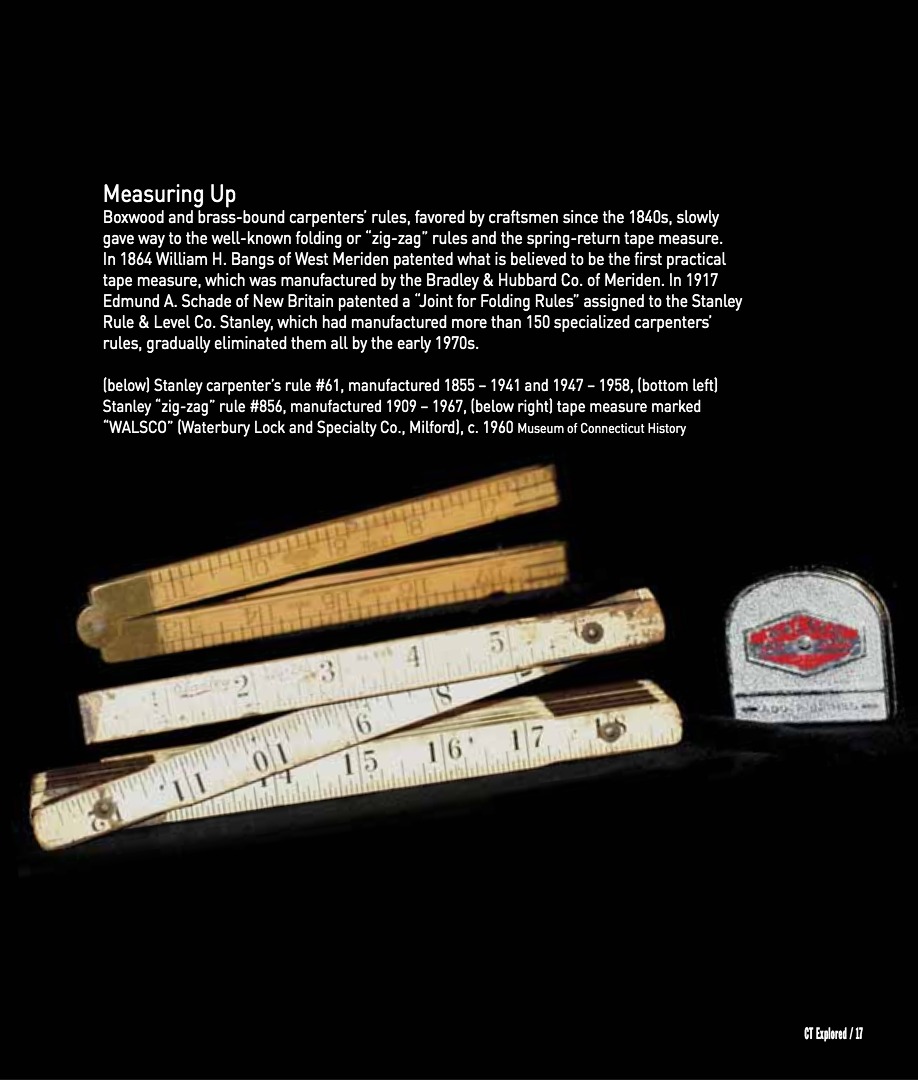

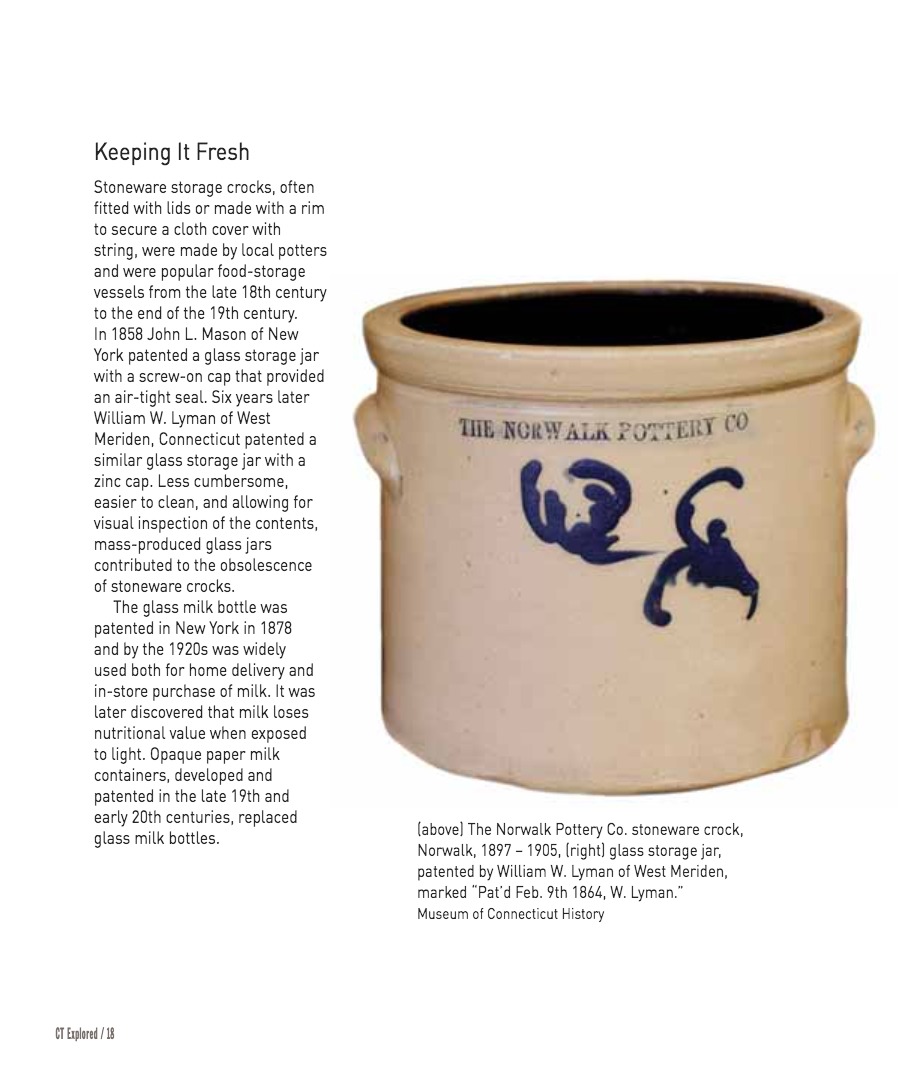

Stoneware storage crocks, often fitted with lids or made with a rim to secure a cloth cover with string, were made by local potters and were popular food-storage vessels from the late 18th century to the end of the 19th century. In 1858 John L. Mason of New York patented a glass storage jar with a screw-on cap that provided an air-tight seal. Six years later William W. Lyman of West Meriden, Connecticut patented a similar glass storage jar with a zinc cap. Less cumbersome, easier to clean, and allowing for visual inspection of the contents, mass-produced glass jars contributed to the obsolescence of stoneware crocks.

The glass milk bottle was patented in New York in 1878 and by the 1920s was widely used both for home delivery and in-store purchase of milk. It was later discovered that milk loses nutritional value when exposed to light. Opaque paper milk containers, developed and patented in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, replaced glass milk bottles.

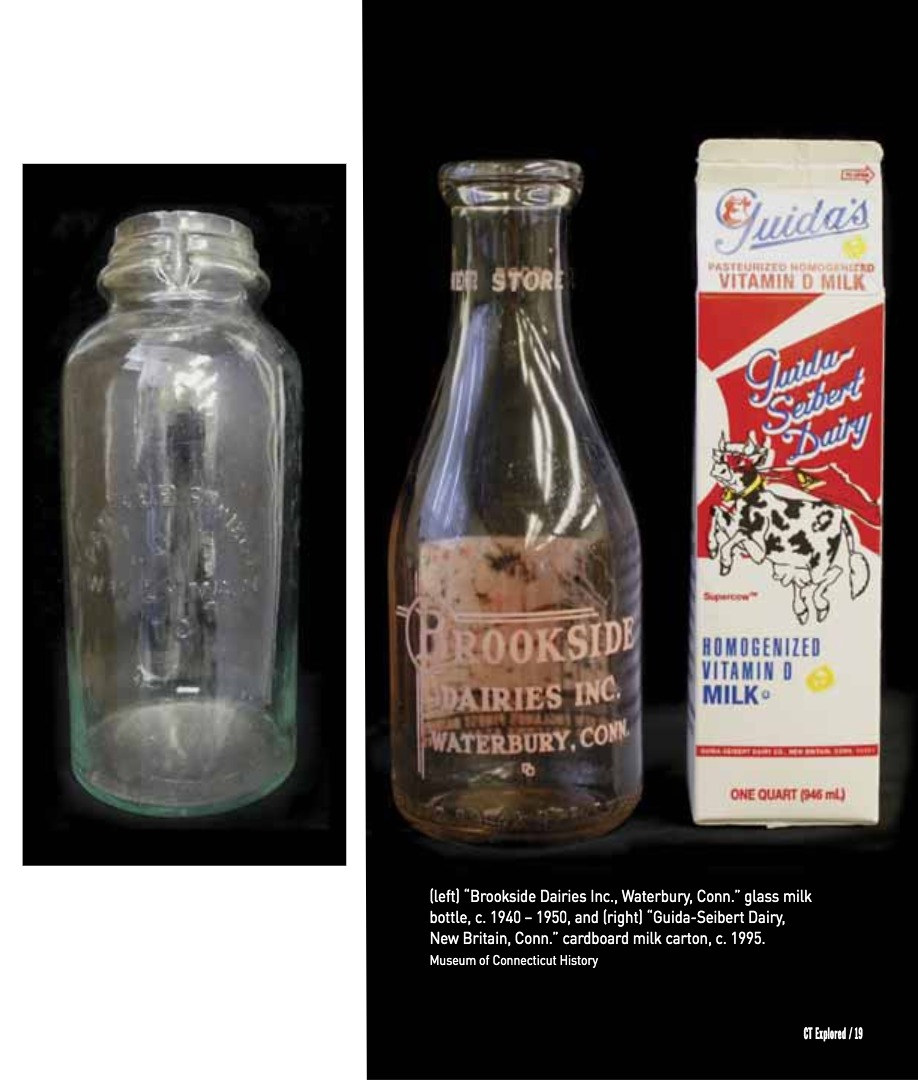

Measuring Up

David Corrigan is curator of the Museum of Connecticut History. He last wrote “Snappy Style from Beacon Falls: The Beacon Falls Rubber Shoe Company,” Summer 2018.