(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Spring 2019

SUBSCRIBE/BUY THE ISSUE!

There was a time when a particularly frigid winter was cause for celebration for the people of Connecticut—especially for Connecticans involved in the ice-harvesting industry.

The advent of the electric refrigerator in the 1930s, with subsequent improvements to the technology, has allowed for the last three generations of Americans to have pretty much constant access to ice. Still, you might encounter old timers who remember their parents or grandparents using the old icebox. So where exactly did that ice come from?

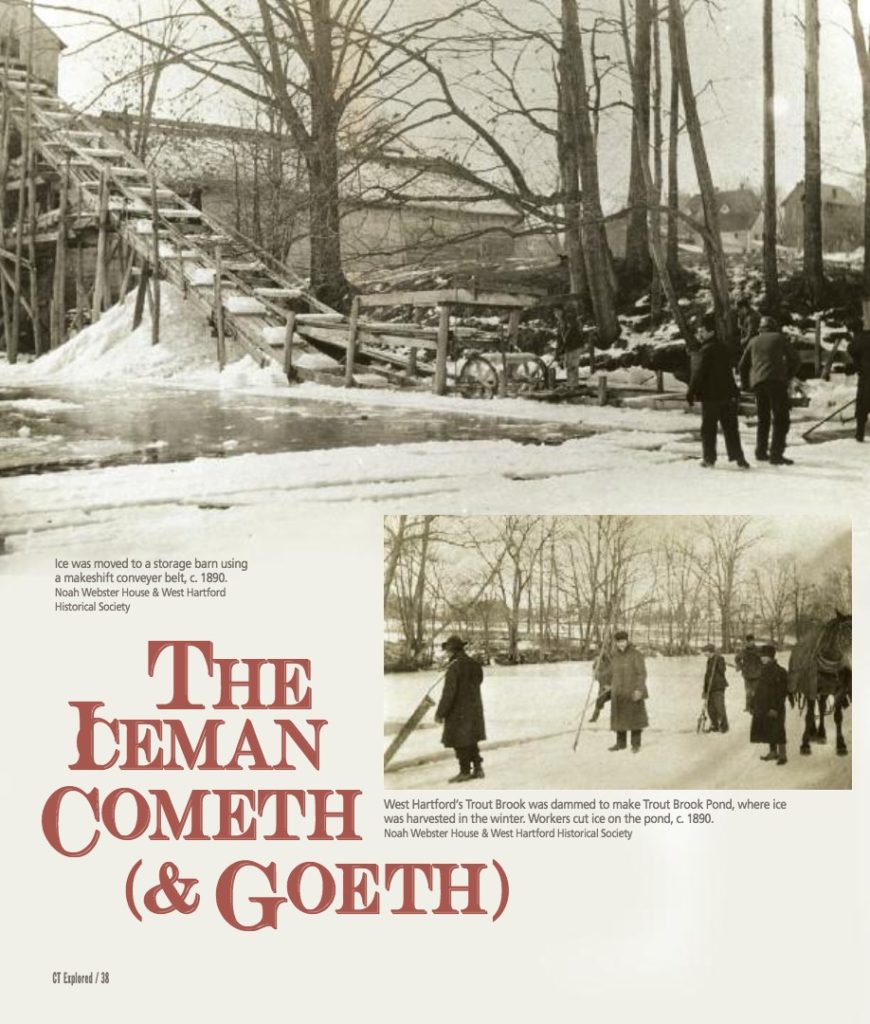

If you lived in West Hartford at the turn of the 20th century, you didn’t have to go far. Edwin Arnold founded the Trout Brook Ice & Feed Co. on Farmington Avenue in West Hartford in 1879, a complex of company buildings situated on the banks of Trout Brook. During the ice harvesting season, a surge of workers came from Hartford to harvest the ice from the frozen-over ponds. The ice was sawed into blocks, loaded into an ice house using an early conveyor belt, and packed in sawdust to insulate it from warming temperatures. The company employed huge red wagons to carry the blocks of ice to homes in the area. In 1895 the company could boast more than 10 delivery wagons and 40 workers for delivery service that was “guaranteed regular and exact.” According toIce Delivery: A Complete Treatise on the Subject (Nickerson & Collins, 1922), ice was typically delivered daily year-round. The ice man looked for a card in clients’ windows indicating the amount of ice they needed that day.

Trout Brook Ice & Feed didn’t just service the Greater Hartford area. Advances in technology meant more factories set up shop along the rivers. Many sources of natural ice in metropolitan areas became contaminated from industrial pollution or sewer runoff. Ice from a pristine rural community like West Hartford, Connecticut became desirable. An influx of immigrants to work in those factories increased the demand for ice. At its peak, Trout Brook Ice & Feed shipped up to 50 train-car loads of ice per day to New York City.

For decades, business was good for Trout Brook Ice & Feed. To keep up with demand, in 1912 Edwin’s son Fred Arnold purchased land along what used to be the Middle Road to Farmington to build another ice pond. According to Celebrate! West Hartford: An Illustrated History(2001), in addition to dredging for the new pond, the company built ice barns for storage and laid trolley racks to carry the ice to Farmington Avenue for shipment throughout the region.

As increases in technology allowed for new refrigeration methods in the early 20th century, there was a chance that the ice industry would die out. However, when the United States entered World War I in 1917, the ice trade rebounded. The nation’s existing refrigeration capabilities were challenged by increased shipments of chilled food to Europe during the war. Factories upped their production of munitions, which used up ammonia and coal that might otherwise be used for refrigeration plants. The ice industry was called upon to relieve the refrigeration burden and maintain adequate supplies.

World War I delayed the ice industry’s collapse, but it could not prevent it. After the war innovations in refrigeration began to be applied to domestic products. The introduction of inexpensive electric motors resulted in the invention of the modern refrigerator that gradually began to replace Grandma’s ice box.

In 1927 Arnold sold Trout Brook Ice & Feed Co. to the Southern New England Ice Co. In a sign of the times, though, that company dissolved nine years later. In the 1930s natural ice harvests declined dramatically and ice warehouses were abandoned or converted for other uses. The ice pond that had been built by Arnold in 1912 took on a new life in 1936, when West Hartford resident Wallace B. Goodwin purchased the land around Wood Pond and Tunxis roads. Goodwin dreamed of creating a residential development that would offer “seclusion” but not “isolation.” Within five years, 44 homes had been sold, and by 1944, a homeowner’s association, the Woodridge Association, had been founded. At the heart of this new development were Arnold’s old ice ponds, now named Wood Pond and Woodridge Lake.

In 1927 Arnold sold Trout Brook Ice & Feed Co. to the Southern New England Ice Co. In a sign of the times, though, that company dissolved nine years later. In the 1930s natural ice harvests declined dramatically and ice warehouses were abandoned or converted for other uses. The ice pond that had been built by Arnold in 1912 took on a new life in 1936, when West Hartford resident Wallace B. Goodwin purchased the land around Wood Pond and Tunxis roads. Goodwin dreamed of creating a residential development that would offer “seclusion” but not “isolation.” Within five years, 44 homes had been sold, and by 1944, a homeowner’s association, the Woodridge Association, had been founded. At the heart of this new development were Arnold’s old ice ponds, now named Wood Pond and Woodridge Lake.

Not a trace of the headquarters of Trout Brook Ice & Feed exists today. There is, however, a street that shares its name, though few would know that an ice company once stood at its intersection with Farmington Avenue. The iceman may have come and gone before our time, but its history is still worth remembering.

Jennifer DiCola Matos is executive director of the Noah Webster House and West Hartford Historical Society. This story is adapted from the museum’s Webster’s West Hartford History blog at https://westhartfordhistory