(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Fall 2016

SUBSCRIBE!

In 1949, 19-year-old William Daniels was working at United Novelty Company, a manufacturing company in Biloxi, Mississippi. In that era, gasoline was used routinely as a cleaning solvent. When Daniels began cleaning a machine, a rat hiding inside it was inadvertently doused in gasoline. The rat ran off and took shelter underneath a heater with a pilot light. Its gasoline-soaked fur caught fire, and it ran again, igniting gasoline fumes and causing an explosion. Daniels was killed.

The case for wrongful death, United Novelty Co. v. Daniels but better known to law students as the Flaming Rat case, raises several questions that were argued in the trial and are presented for visitors to contemplate in the new American Museum of Tort Law in Winsted, Connecticut. It’s just one of many cases that afford visitors the opportunity to understand the evolution of consumer rights and tort law in the United States.

Tort law is the system of law that governs claims by victims for harm caused by wrongdoing leading to civil legal liability. Tort law is based on the premise that goods and services offered to common people will be safe and won’t cause harm and that workers may reasonably expect to be safe from harm on the job. As visitors will learn as they enter the museum, American tort law has its roots in Anglo-Saxon England. If a person was found to have harmed an individual, they were responsible for paying damages. British colonists carried that system to North America, where it has remained in place even as it has evolved and been refined through the years as new cases are brought to court and litigated.

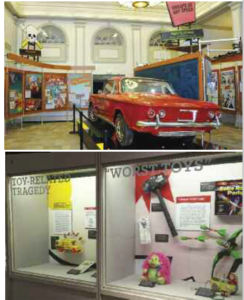

In 1965 Hartford lawyer and University of Hartford lecturer Ralph Nader (born February 27, 1934) entered the public eye with his book Unsafe at Any Speed: The Designed-in Dangers of the American Automobile (Grossman, 1965) about the unsafe practices of the American automobile industry—with Chevrolet’s Corvair as Exhibit A—and the ensuing Nader v. General Motors Corp. case. He had started researching the industry while attending Harvard Law School (from 1955 to 1958). After the book’s publication, Connecticut Senator Abraham Ribicoff asked Nader to testify before a U.S. Senate subcommittee on automotive safety. The National Traffic and Motor Vehicle Safety Act, developed by the senate’s automotive safety subcommittee, was passed later that year.

That was just the beginning of Nader’s long career in promoting consumer safety through advocacy and the practice of tort law. Fifty years later, in 2015, Nader founded in his hometown of Winsted a museum dedicated to the history of tort law in America.

The American Museum of Tort Law is housed in a 1910 Beaux Arts-style former bank building. The museum offers visitors a jam-packed experience in every corner. One prominent feature is an 11-minute video tracing tort law’s roots and featuring several experts on tort law, including Nader, Joseph R. Page, director of the Center for the Advancement of the Rule of Law in the Americas at Georgetown Law, and Joanne Doroshow, executive director of the Center for Justice and Democracy at New York Law School.

The American Museum of Tort Law is housed in a 1910 Beaux Arts-style former bank building. The museum offers visitors a jam-packed experience in every corner. One prominent feature is an 11-minute video tracing tort law’s roots and featuring several experts on tort law, including Nader, Joseph R. Page, director of the Center for the Advancement of the Rule of Law in the Americas at Georgetown Law, and Joanne Doroshow, executive director of the Center for Justice and Democracy at New York Law School.

One of the first galleries covers precedent-setting cases such as Daubert v. Merrell Dow, in which the courts debated what makes someone an expert witness, and Greenman v. Yuba Power Products, in which the courts debated timely notice of a worker’s injury. Another gallery displays and discusses dangerous toys, an area of keen interest to the late attorney Edward M. Swartz, a pioneer in toy safety and the first to publish the famed annual “10 Worst Toys” list. This exhibit features several controversial toys such as bottle rockets and slingshots and offers information about many toy-safety cases.

Once the museum secures sufficient funding, a full-size model of a courtroom will be constructed. The courtroom will be used to educate visitors and students, provide a platform for museum-goers to express their opinions, and even reenact landmark cases for live audiences and web-cast. The museum will invite law students to participate in mock-trial competitions. The museum also hopes to host a satellite presence in Washington, D.C. and to develop a traveling exhibition program.

As the museum’s brochure quotes Nader, “The history and achievement of the common law of Torts—and those who helped shape it—should be celebrated in order to be preserved and improved. Help us advance public understanding and recognition of this pillar of American justice” by visiting the American Museum of Tort Law.

Ethan Manis graduated from the University Of Hartford last spring and was an intern for Connecticut Explored.

Connecticut Explored received support for this publication from the State Historic Preservation Office of the Department of Economic and Community Development with funds from the Community Investment Act of the State of Connecticut.

Connecticut Explored received support for this publication from the State Historic Preservation Office of the Department of Economic and Community Development with funds from the Community Investment Act of the State of Connecticut.