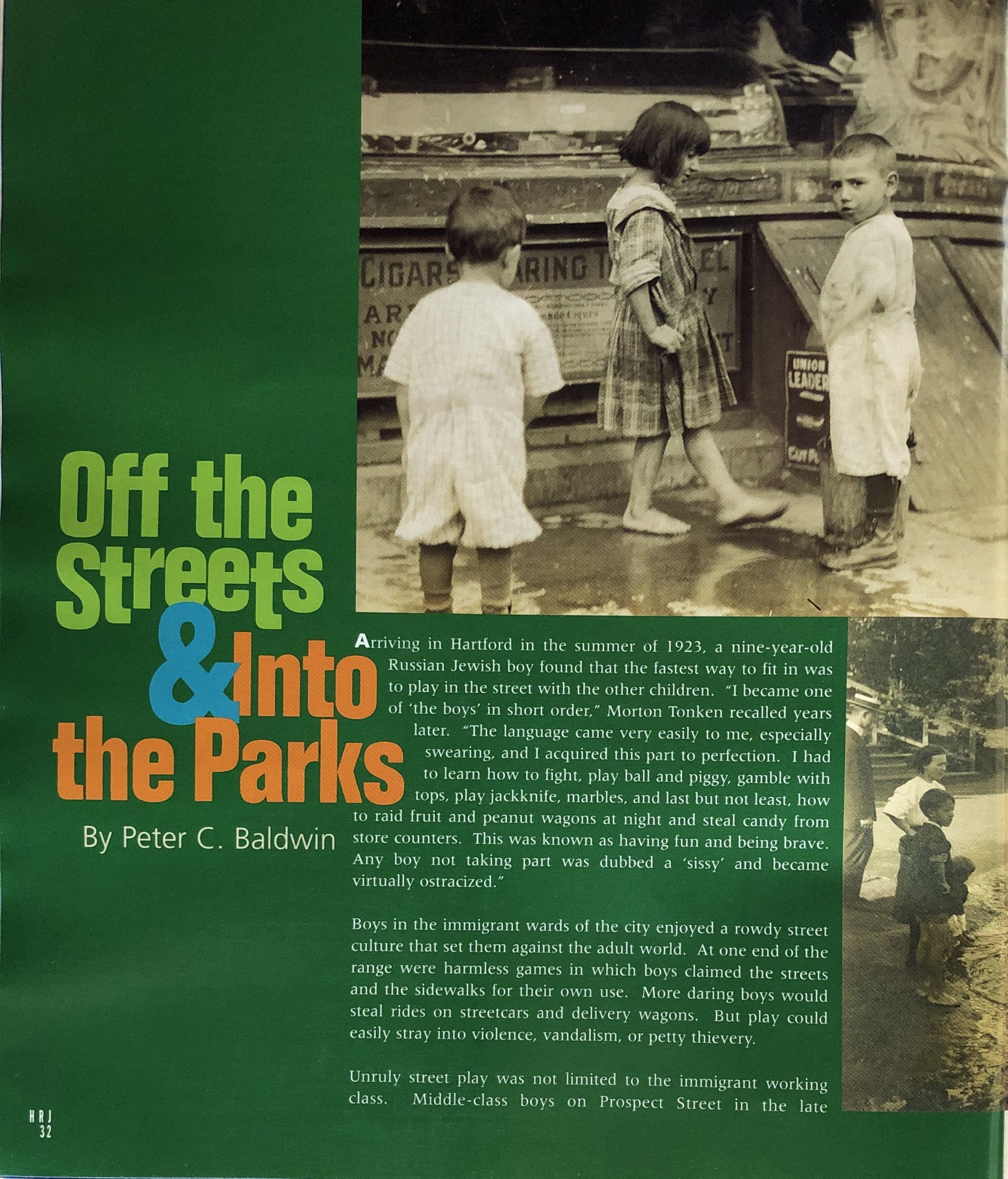

top: Playing in a puddle on the East Side of Hartford, 1913. Woman Suffrage Association, “Vice Campaign,” State Archives, Connecticut State Library

By Peter C. Baldwin

© Connecticut Explored Inc. Spring 2003

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

Arriving in Hartford in the summer of 1923, a nine-year-old Russian Jewish boy found that the fastest way to fit in was to play in the street with the other children. “I became one of ‘the boys’ in short order,” Morton Tonken recalled years later.

The language came very easily to me, especially swearing, and I acquired this part to perfection. I had to learn how to fight, play ball and piggy, gamble with tops, play jackknife, marbles, and last but not least, how to raid fruit and peanut wagons at night and steal candy from store counters. This was known as having fun and being brave. Any boy not taking part was dubbed a ‘sissy’ and became virtually ostracized.

Boys in the immigrant wards of the city enjoyed a rowdy street culture that set them against the adult world. At one end of the range were harmless games in which the boys claimed the streets and the sidewalks for their own use. More daring boys would steal rides on streetcars and delivery wagons. But play could easily stray into violence, vandalism, or petty thievery.

Unruly street play was not limited to the immigrant working class. Middle-class boys on Prospect Street in the late 19th-century “romped up and down the street and through all the backyards, which they regarded as public property,” remembered one of these boys. Yet it was the play of working-class, immigrant children that most alarmed Progressive Era reformers. Growing in numbers as a result of the great waves of European migration, crammed into what reformers believed to be pathological slum environments, and standing apart from mainstream culture, these children seemed to pose a grave danger to the values of the native-born middle class. Reformers sought some way of taming and Americanizing these children, lest they grow up wholly estranged from mainstream life.

Unruly street play was not limited to the immigrant working class. Middle-class boys on Prospect Street in the late 19th-century “romped up and down the street and through all the backyards, which they regarded as public property,” remembered one of these boys. Yet it was the play of working-class, immigrant children that most alarmed Progressive Era reformers. Growing in numbers as a result of the great waves of European migration, crammed into what reformers believed to be pathological slum environments, and standing apart from mainstream culture, these children seemed to pose a grave danger to the values of the native-born middle class. Reformers sought some way of taming and Americanizing these children, lest they grow up wholly estranged from mainstream life.

Inner-city children and youths were thought to be trapped in congested, man-made environments, where they were battered by a constant volley of sensations. Reformers, influenced by a new understanding, namely, that the growing child passed through discrete, quasi-evolutionary stages, feared that overstimulation could disrupt proper development. Desires for social control and for proper child development merged into a sophisticated campaign to reform the use of urban space. For the first time, areas within the city were specifically designated for children’s recreation. Playgrounds, gymnasiums, and athletic fields were built in which play could be directed and in which, it was hoped, proper child development could take place. The unexpected growth of automobile traffic also contributed to this effort. By the late 1920s, these twin forces — the playground movement and automobile traffic — had resulted in the growing separation of children’s play from adults’ use of the streets.

The city parks were actually a fairly recent phenomenon. It wasn’t until the 1890s that Hartford created a park system to provide recreational spaces for every section of town. By that time, trolley service and population growth were spurring a geographic expansion of the city and creating neighborhoods as far as two miles from Bushnell Park. During 1894 and 1895, in what came to be known as Hartford’s “Rain of Parks,” five major parks were either given to the city or purchased. Donated were Elizabeth Park on the Hartford-West Hartford border; Pope Park, donated by the industrialist Albert Pope and located conveniently close to his Capitol Avenue bicycle factory; and Keney Park, which stretched through the North End and across the city line into Windsor. The city’s purchases were Riverside Park, on the Connecticut River northeast of downtown and Goodwin Park, on the Wethersfield town line. A sixth major addition to the park system was the former estate of the arms manufacturer Samuel Colt, which his widow, Elizabeth Colt, left to the city in 1905.

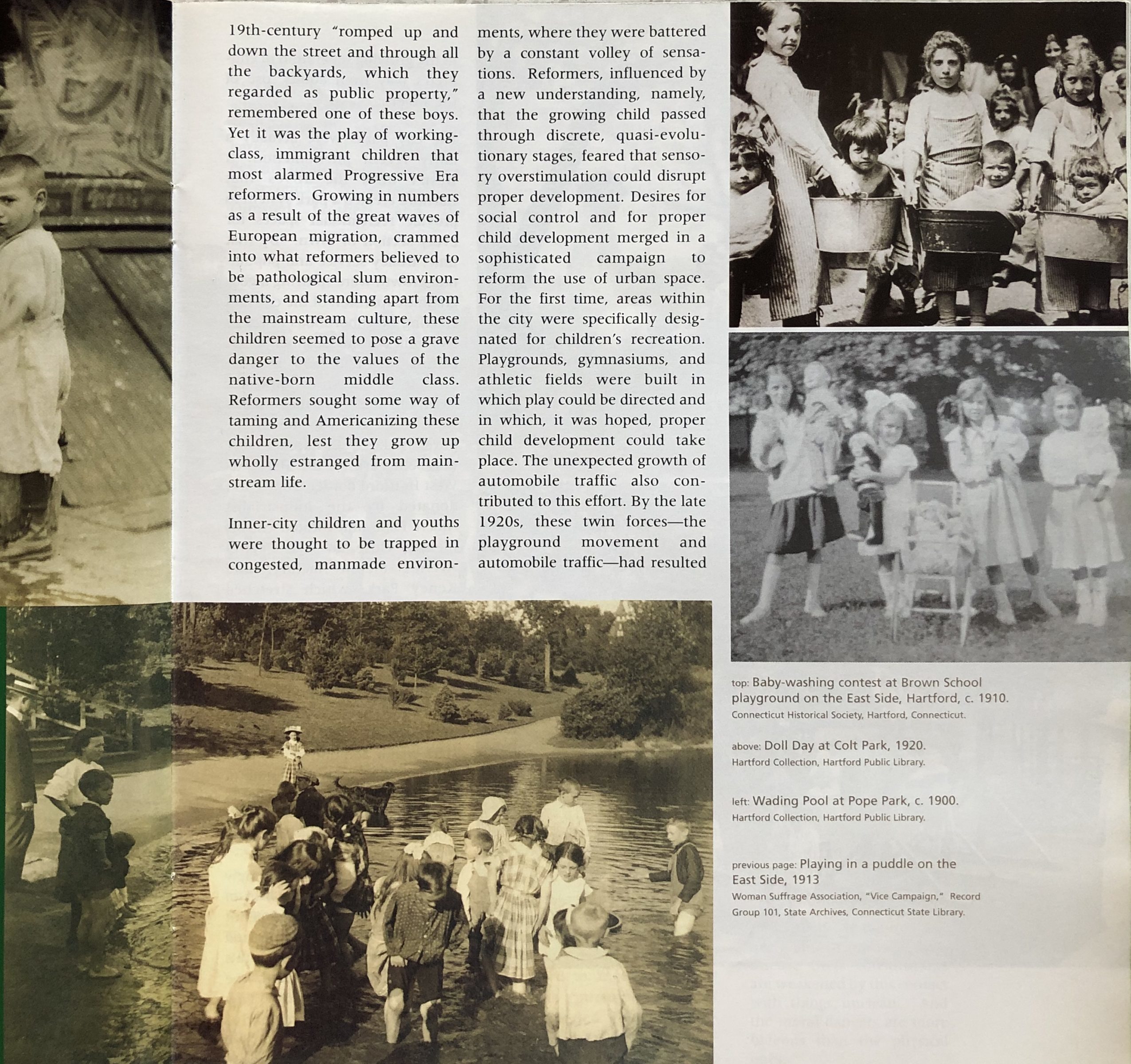

The designs for most of the new parks were done by the firm of Olmsted, Olmsted, and Eliot (later renamed “Olmsted Brothers”), which was led at this time by John C. Olmsted, the stepson of Frederick Law Olmsted, the Hartford native who had designed New York City’s Central Park. John Olmsted’s primary objective in Hartford was to create landscapes that took advantage of the “natural scenery available in the vicinity” of the park. Most of the new park designs treated active recreation as secondary. Nevertheless, the Olmsted brothers and the park commissioners made some provision for active recreation even within this naturalistic playground, including children’s play spaces such as Pope Park’s “Little Folks Lawn,” and its two baseball fields, labeled Nethermead and Thithermead. Riverside Park, located close to the immigrant East Side neighborhood, was designed mainly for the active recreation needs of the poor, though John Olmsted skirted that issue. The park included baseball fields, a “Little Folks Lawn,” and a wading pool that immediately drew crowds of children.

The designs for most of the new parks were done by the firm of Olmsted, Olmsted, and Eliot (later renamed “Olmsted Brothers”), which was led at this time by John C. Olmsted, the stepson of Frederick Law Olmsted, the Hartford native who had designed New York City’s Central Park. John Olmsted’s primary objective in Hartford was to create landscapes that took advantage of the “natural scenery available in the vicinity” of the park. Most of the new park designs treated active recreation as secondary. Nevertheless, the Olmsted brothers and the park commissioners made some provision for active recreation even within this naturalistic playground, including children’s play spaces such as Pope Park’s “Little Folks Lawn,” and its two baseball fields, labeled Nethermead and Thithermead. Riverside Park, located close to the immigrant East Side neighborhood, was designed mainly for the active recreation needs of the poor, though John Olmsted skirted that issue. The park included baseball fields, a “Little Folks Lawn,” and a wading pool that immediately drew crowds of children.

Still, this was inadequate as Hartford’s streets remained the main venue for play for many children in the early 20th century. As uncontested spaces for play such as vacant lots became scarcer in the building boom around the turn of the 20th century, children just adapted their games. In some, such as ring-o-levio or hares-and-hounds, the urban environment was an essential part of the game and added interesting and challenging dimensions. For example, a winning tactic in the chase game of hares-and-hounds was running through a store and out the back — the hares usually made it through quickly enough to avoid interference, but the shopkeeper was roused to anger in time to stop the pursuing hounds. Reform-minded Hartford residents viewed such play as unacceptable. In the Report of the Civic Club for 1905, the club secretary wrote:

No thoughtful person needs any arguments to prove to him that the streets are not a desirable spot for children. The most unreflecting, the most selfish person could not pass through the streets of our East Side on a blazing July day without wishing to carry the children off to a more suitable sport. They sit on the curbstone and extract strange substances from the mud of the gutter, they play, more or less peacefully, in the path of wagons and horses, they rush in front of electric cars, screaming with delight at the motorman’s frantic bell. If they do not lose a limb or contract a fatal disease their constitutions are weakened by this contact with things unclean. And the moral dangers are more hideous than the physical ones.

This was an assessment with which Hartford’s future superintendent of parks, George A. Parker, would agree. Superintendent of parks from 1906 to 1926, Parker was a leader in efforts to move child’s play out of the street and into the parks and playgrounds. He was driven by a belief that the city could devour its young; it threatened to corrupt the children and, through the poisonous effects of the saloon, the brothel, and tobacco, dump them on what he called “the human scrap heap.” He observed:

The family no longer works together, the man goes to his place, and the woman altogether too often goes to her work, the children are in school, the young boy and girl [each]to their own particular task, [until]the coming together again at the evening meal. Formerly, the evening was spent together in the house, but the housing conditions are such among too many of our workers that they cannot and will not stay in the house. The man, the boy and the girl usually separate for the evening each to their own amusement, the mother more often stays in the home.

Yet Parker believed that a determined effort by the citizenry could tame the urban monster, suppress its most dangerous sources of immorality, encourage the growth of positive influences, and create a “sin-proof city.” In assessing the problem, Parker employed more sophisticated conceptual tools than had been previously used. Like his counterparts in recreation work throughout the country, Parker drew on new ideas of child development being articulated in the late 1890s and early 1900s by Granville Stanley Hall and Luther Halsey Gulick.

top: A handwritten note on the obverse of the photo reads: “Children playing in the sandbox of the Curtis H. Veeder playground at Elizabeth Park, (very significant since the families of these very children opposed the opening of the playground.)” Hartford Collection, Hartford Public Library. bottom: Children supervised at play in an unidentified park. Hartford Collection, Hartford Public Library

According to Hall, a child psychologist and the president of Clark University, children passed through stages of development that recapitulated the prehistoric cultural evolution of the human race. Gulick, physical education director first for the Young Men’s Christian Association International College and later for the New York City public schools, argued that proper physical and moral development required that children act out instinctual drives through age-specific types of play. For instance, track-and-field sports and tag games were appropriate for boys age 7 to 12, who were driven by pre-savage, individualistic hunting instincts. Adolescent boys, whose development corresponded to that of hunting tribes, needed more complex team sports. Proper development would prepare boys to play constructive roles in society when they reached adulthood.

The chief dilemma was how much structure to impose on children’s play. The Civic Club had created a six-week summer “vacation school” in 1897 to serve Hartford’s East Side children age 6 to 14. The vacation school tried to simultaneously educated, edify, and entertain the children. Initially offered in East Side’s Brown School, the vacation school program grew quickly over the the next few years and spread into outdoor spaces. With charitable donations and financial aid from the city government, the Civic Club expanded the program. By 1900 about a thousand students were enrolled in three schools, and an equal number of others came to use the three supervised playgrounds. In 1901 the city over management of the vacation schools and in 1904 transferred them to the public school system.

Throughout this period, there was a tug-of-war between education and fun. When the emphasis shifted to education after the school system took over in 1904, children expressed their displeasure by dropping out. Major changes were needed to win them back. Accordingly, the vacation school directors in 1905 offered park days with no fixed programs; children were allowed to devote their time to whatever form of recreation they wanted and a marked increase in attendance was noted. Average daily attendance reached 4,631 in July 1912 and 6,808 a year later. Having focused on luring children off the streets, the vacation schools had become mainly a program to provide play space. By 1913 the vacation school program had been rechristened “Recreation Work in Summer” and taken over by the parks department. But efforts to direct play continued, ranging from children’s flower and vegetable gardens at Riverside Park to elaborately choreographed outdoor pageants in which hundreds of children danced in formation and waved flags. Describing a 1914 event in Keney Park that involved 2,500 children and 4,800 flags, a Courant reporter commented snidely that it

epitomized both the spirit of democracy of our public schools and the trend of the times in organized playing. For nowadays, it is not permitted that the pupil run and jump and shout as he will, for such playing needs no supervision; he must stand thus and so, and move his arms and legs in unison with hundreds of other little arms and legs, thus and so.

Degrees of discipline also varied from one playground to another. Of the 11 playgrounds opened in 1912, 7 offered directed play and 4 offered free play. George Parker wanted more free play, which meant that no child was told to participate in a specific game or to use a specific piece of equipment. Children supposedly had the freedom, within limits, to follow their instinctual drives. “Directed play, like the schools, is from the outside in, while free play is from the inside out,” Parker wrote in 1919. Yet in practice the distinction between free and directed play was blurred. Even when the play was “free,” the children were often watched by supervisors, most of whom in the 1910s were employees of the school system. These supervisors sought to keep rough street behavior from contaminating the playground and enforced a detailed list of rules. They instructed the younger children in the playground in the proper use of the slides and swings, prevented anyone from monopolizing the equipment, kept order in the waiting lines, stopped boys from teasing girls, and broke up fights. The staff hoped not merely to keep order, but also to teach children to be considerate, to have “discipline” and — once they were old enough — to join the spirit of team play.

Uncomfortable with the more overt forms of directed play, Parker placed his greatest hopes of the simple creation of separate play spaces. Here, he was guided both by his ideas of child development and by his belief that the model of “segregation” that he admired in the South could be applied in a nonracial way to Hartford’s recreation. Parker believed in a “segregation of play activities by sex and age periods with suitable and seperate provisions for each,” as he wrote in 1915. It was not necessary in every case for each age group to have its own field or playground area, but the groups should be kept apart and occupied at different forms of play. The parks department also built some gender-specific facilities, such as an “outdoor gymnasium” for girls in Pope Park.

Vacation School gardens in Colt Park, 1918. The rear of the Colt mansion and greenhouses are visible in the background. Hartford Collection, Hartford Public Library

Parker argued in 1912 that the city should provide a playground in every neighborhood with 600 children under the age of 12, and in fact “the city should be prepared to furnish sandboxes and rope swings wherever a neighborhood of thirty or more children ask for them.” But such ambitious plans were frustrated by financial limitations. Parker and his allies on the juvenile commission tried everything they could think of to increase the number of playgrounds; they even attempted to lease land from private owners. But even with the addition of more school playgrounds in the late 1920s, the total number of playgrounds operated by the parks department and school system rose only to 27 by 1930. Adding to the problem of limited playground space was the fact that many children preferred to play elsewhere. W.J. Hamersley, the secretary of the juvenile commission, admitted in 1914 that most play took place in the street.

The rapid growth of automobile traffic in the 1910s and 1920s helped discourage some of this persistent street play. Traffic casualties soared in these years and most of the victims were pedestrians; children — notable in the immigrant wards — were particularly likely to be killed or injured. Playground advocates in the 1910s emphasized the need to get the children away from traffic, as did the Automobile Club of Hartford, whose official publication lamented in 1919 that

It is unfortunate that in some parts of the city it seems impossible to prevent children from playing in the streets. We realize that in some sections there is not any other place where they can play, but if they could only be taught to understand the danger of running out into the roadway, and that their safety depended upon their playing on the sidewalk, there would be fewer accidents. Only recently one of our members called at the club in regards to the boys playing marbles in the streets. This is very dangerous as the boys are so intent on their play that they think of nothing else and are apt to run in front of a team [horse and wagon]or automobile.

Recreation officials, Hartford police, schools, and the Automobile Club worked together in the 1910s to discourage street play. Police crossing guards both supervised schoolchildren and sought to teach them about traffic safety. In a 1913 article, the Courant reported that one traffic policeman “finds the very little children, the kindergarten tots, the easiest to look after. They have become educated so that they pause the minute they reach the curb and wait for the signal that it is safe for them to cross.” The Automobile Club of Hartford took traffic safety education directly into the schools in a “Safety First” campaign in the spring of 1914. Members of the club gave speeches at schools throughout the city, telling the students about the dangers of street play, and urging them to cross only at the corners and only after looking both ways. The club printed placards — that were posted prominently in the schools as well as in store windows — with photographs showing dangerous activities to avoid such as playing ball in the street. It also printed smaller instructional cards to distribute to every student.

Still, children did not entirely abandon the streets. Many of them seemed to have ignored the traffic safety lessons. Instead, traffic and police interference had the effect of segregating street use. Though the dangers and frequent interruptions created by motor vehicles in the 1910s and 1920s made play impossible in the busy streets, children continued to play in the side streets and alleys of Hartford’s tenement districts. Morris Cohen, who grew up in a poor Jewish neighborhood north of the downtown recalled how traffic affected boys’ games in the 1910s: “We used to play some baseball, we played some football, and we learned to play piggy in the streets, not on Windsor Street itself because it was too busy, but we would go to Portland Street, to Pequot Street, or North Street.”

Thus, while Parker and his allies did not fully transform Hartford’s play environment, the playground campaigns and the growth of traffic combined to create more sharply defined borders in the geography of urban play.

Peter C. Baldwin is an assistant professor of history at the University of Connecticut. A former resident of Hartford, he worked as a reporter for the Hartford Courant from 1984 to 1991. This article is adapted from his book, Domesticating the Street: The Reform of Public Space in Hartford, 1850-1930 (Ohio State University Press, 1999).

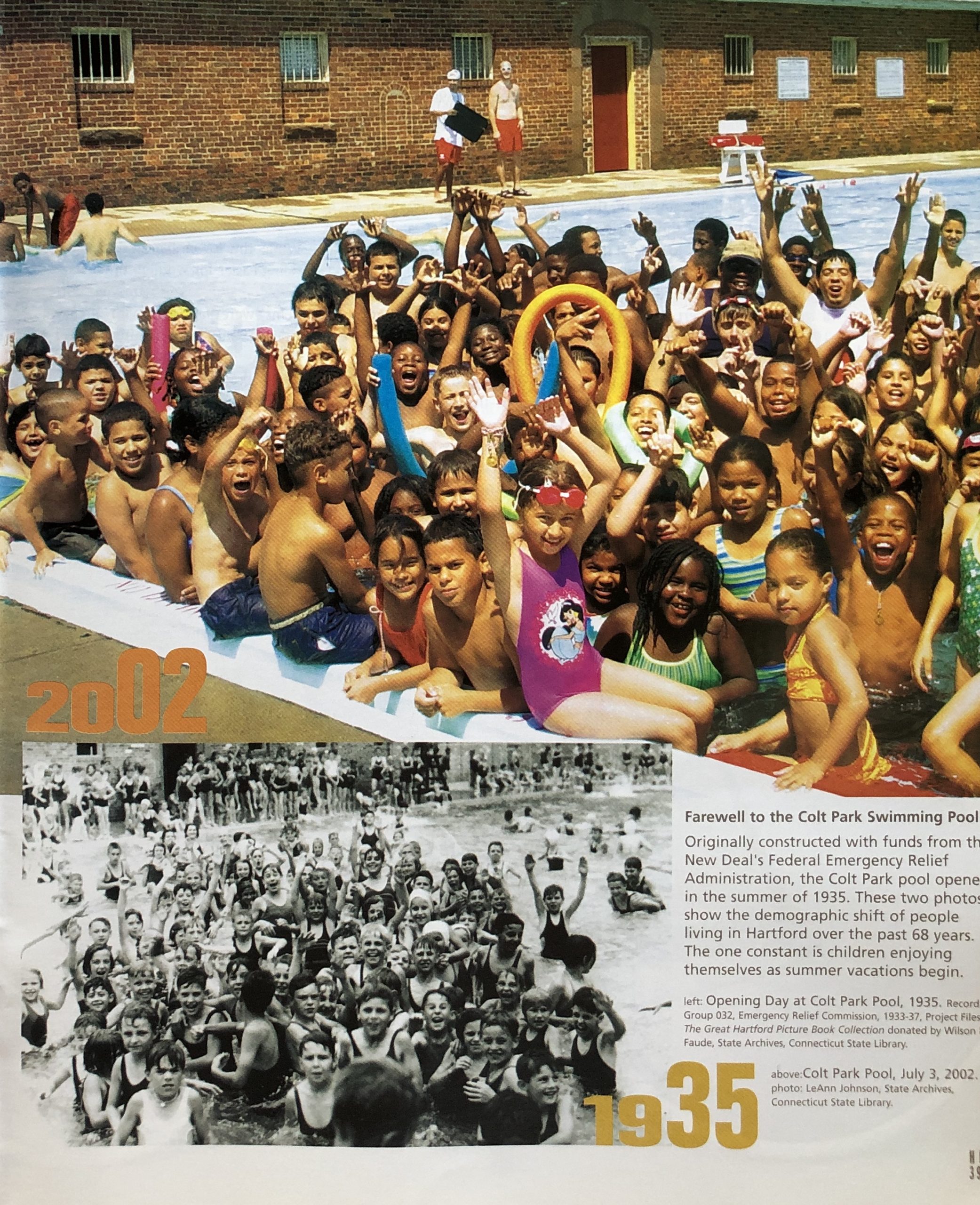

Farewell to the Colt Park Swimming Pool

Farewell to the Colt Park Swimming Pool

Originally constructed with funds from the New Deal’s Federal Emergency Relief Administration, the Colt Park Pool opened in the summer of 1935. These two photos show the demographic shift of people living in Hartford over the past 68 years. The one constant is children enjoying themselves as summer vacations begin.

top: Colt Park Pool, July 3, 2002. photo: LeAnn Johnson, State Archives, Connecticut State Library

bottom: Opening day at Colt Park Pool, 1935. Record Group 032, Emergency Relief Commission, 1933-37, Project Files. From The Great Hartford Picture Book Collection, State Archives, Connecticut State Library

Read more!

About Childhood in Connecticut history [see Topics on the main menu]

About Landscape/Environment [See Topics on the main menu]