(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Summer 2020

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

In a long view of the history of this land, women’s suffrage was a step in a natural re-balancing of governance systems. From Native cultural perspectives, women electing representatives to government is nothing new to the place we now call the State of Connecticut, and women’s suffrage was a step toward restoring the natural order of equity in governance between men and women that was disrupted by settler colonialism 400 years ago.

From the signing of the U.S. Constitution in 1787 and the Bill of Rights in 1791, American women did not have a uniform right to vote for elected representatives in American democracy until the passage of the 19th Amendment in 1920. But, even with the passage of the amendment, black voters were still denied voting rights in some states until the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Native voting rights wouldn’t be achieved nationwide until 1962 when Utah became the last state to remove formal barriers to Native voters, as journalist Becky Little documents. [See history.com/news/native-american-voting-rights-citizenship.]

The Mashantucket Pequot Museum and Research Center’s History & Culture E-book beautifully illustrates how human occupation of Connecticut began more than 10,000 years ago. The coastal Algonquin Native peoples that occupied this territory developed entire languages, cultures, and sustainable ways of living here — all in a relative natural harmony that involved seasonal migration. Communities congregated in large coastal villages in the summer to take advantage of the abundant fishing resources in Long Island Sound. The winter saw those communities break up and spread out over the landscape to hunt. Over time, cultures, languages, kinship systems, and sophisticated forms of governance evolved.

When English colonists first began colonizing southern New England they often remarked about local tribal ways of life through their patriarchal worldview. In 1624 Edward Winslow in Good News From New England observed about Plimoth Colony that,

“The men employ themselves wholly in hunting, and other exercises of the bow, except at some times they take some pains in fishing. … The women live a most slavish life, they carry all their burdens, set and dress their corn, gather it in, seek out for much of their food, beat and make ready the corn to eat, and have all household care lying upon them.”

Winslow and other early English colonists — for whom the norm was men as farmers — perceived Native men as forcing Native women into “slavish” labor. The structure of Native societies, however, was actually quite different. The cosmology of the tribes of this region sees the Earth or the land as maternal or a mother creating and sustaining life. Native women in some areas produced as much as three-quarters of the food supplies for their villages, in estimates from Native American Netroots, an online forum for the discussion of issues affecting the indigenous peoples of the United States, and based on the observances of Roger Williams, founder of the Colony of Rhode Island.

Winslow and other early English colonists — for whom the norm was men as farmers — perceived Native men as forcing Native women into “slavish” labor. The structure of Native societies, however, was actually quite different. The cosmology of the tribes of this region sees the Earth or the land as maternal or a mother creating and sustaining life. Native women in some areas produced as much as three-quarters of the food supplies for their villages, in estimates from Native American Netroots, an online forum for the discussion of issues affecting the indigenous peoples of the United States, and based on the observances of Roger Williams, founder of the Colony of Rhode Island.

Control over life-giving food production created equity with men in terms of power and leadership. The decision-making process in governance, such as selecting a new sachem, was one of consensus of all their people. Political power was also embedded culturally in matrilineal kinship structures. Elder women in these societies provided the path of kinship by which duties, responsibilities, history, and power emanated, and in a colonial sense they were the first real “landowners,” sometimes controlling vast stretches of territory. While men are often chosen as sachems of Southern New England tribes, the inheritance of power is based on matrilineal descendancy. The absence of a suitable male heir, such as during an epidemic, resulted in matrilineal inheritance of leadership by women—a rare, but not unheard of, occurrence.

After the Pequot War ended and the Treaty of Hartford was signed in 1638, the English began to earnestly colonize the area, first on the long tidal river Quinetucket, one of various similar versions of Algonquin dialectical terms that would yield the anglicized name Connecticut. With English arrival came the English language and English way of life. One of the English customs that had great impact on Native peoples was that the English gave individual men rights to “own” plots of land for the purpose of “improving” it, as described in Amy Den Ouden’s Beyond Conquest: Native Peoples and the Struggle for History in New England (University of Nebraska Press, 2005). This meant building fences to mark a particular plot, cutting trees, building year-round housing, cultivating soil for yearly crops, and raising cows, chickens, and pigs for slaughter. Plots of land (some of them vast areas) increasingly fell under this English custom whereby only men owned the property. This completely upended the system of Native land management that had persisted for thousands of years. Under colonization, the rights of women to own land were not always guaranteed or recognized. This is crucial to early ideas of suffrage rights in colonial America, where only landowning men were allowed the right to vote.

Much of colonial history tends to focus on disease and conflict between Natives and colonists. But it was after these early conflicts and epidemics that the largest dispossession of land of Native peoples into the hands of the English took place, creating a “New England.” During the late 17th and through the 18th centuries, dispossession happened not by military conquest but by agreements recorded through paper documents. The signatories of these paper land deeds and agreements were often identified by the English through their cultural lens seeking out and finding male signatories.

The legitimacy of these early land deals comes into question from a Native point of view. In local Native matrilineal societies, women controlled the land and its resources. What rights did Native men have to mark a piece of paper and give those powers away under that cultural construct? There is no easy answer, but it certainly complicates the narratives of the founding of Connecticut’s towns and cities.

The lasting effect of colonial land possession were the foreign forms of patriarchal government imposed on newly acquired “American” lands. Under this form of governance, extraction from the land and commodifying property for profit defined success. This is in stark contrast to Native cultural values of equity in leadership and women’s rights to govern the land they managed. The early success of English colonies under their definition resulted in land loss and legal challenges as the 18th century progressed.

After the 17th century, some land was still in control of Native hands. In these small pockets of Native land ownership, early colonial land deals put control of land in the hands of Native men, but that status quo did not remain for long. As Native landowning men in this era died, the following generations began seeing land ownership rights under English rule transferred back to the women of the families or communities. Inheritance rights recorded in wills passed down the rights of land ownership to sisters, daughters, and nieces. Kathleen Bragdon explored this phenomenon in Native People of Southern New England, 1650 – 1775 (University of Oklahoma Press, 2020). Family wills (especially those written in a family’s dialect of Algonquin) become a useful source for examining how matrilineal descendancy and control of land and wealth fell back into the hands of women in Native communities in the 18th century. In her discussion of land inheritance in the later colonial period, inheritance practices “recorded in Native languages or by Indians themselves” cites examples of Native landowners handing down land to sisters and daughters. In one case, in 1755 a Natick (Massachusetts) woman named Elizabeth Pognit willed one pound of her wealth to her husband and the remainder of her estate, including all her lands and belongings, to her granddaughter.

After the 17th century, some land was still in control of Native hands. In these small pockets of Native land ownership, early colonial land deals put control of land in the hands of Native men, but that status quo did not remain for long. As Native landowning men in this era died, the following generations began seeing land ownership rights under English rule transferred back to the women of the families or communities. Inheritance rights recorded in wills passed down the rights of land ownership to sisters, daughters, and nieces. Kathleen Bragdon explored this phenomenon in Native People of Southern New England, 1650 – 1775 (University of Oklahoma Press, 2020). Family wills (especially those written in a family’s dialect of Algonquin) become a useful source for examining how matrilineal descendancy and control of land and wealth fell back into the hands of women in Native communities in the 18th century. In her discussion of land inheritance in the later colonial period, inheritance practices “recorded in Native languages or by Indians themselves” cites examples of Native landowners handing down land to sisters and daughters. In one case, in 1755 a Natick (Massachusetts) woman named Elizabeth Pognit willed one pound of her wealth to her husband and the remainder of her estate, including all her lands and belongings, to her granddaughter.

This is important to the cultural continuity of Native populations in Connecticut and beyond. Women, through working the land and performing the duties of “landowners” under colonization, maintained the existence of Native communities through the harshest times of settler colonialism. Reservation lands initially created by the colonial Connecticut General Assembly in the 17th century went through rapid eras of diminishment in the 18th century.

As is well documented in the records of the Connecticut Colony, reservations were encroached upon as the burgeoning English settler population put pressure on the availability of land. Sometimes lands were given away under governmental orders. This process of diminishing Native-held lands continued through the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries.

Mary Momoho (also known as Oskoosooduck and Mary Sowas), daughter of the great Pequot sachem Momoho, became active and prominent in land affairs for the Eastern Pequots on Lantern Hill beginning in 1723 with a petition about Eastern Pequot land rights, as Paul Grant-Costa documents in a post for the Yale Indian Papers Project (February 17, 2015). Subsequent decades saw her become the sachem of the community and successfully lobby against settler encroachment. In 1751 she convinced the Connecticut General Assembly to pass legislation to protect her community’s interests and provide a period of stability during these years of land loss.

After Connecticut’s statehood, the remaining recognized Connecticut tribes lived on reservations. The Paugussett people had a reservation established in 1639 by the Connecticut General Assembly at Golden Hill in present-day Bridgeport, the Eastern Pequot Reservation on Lantern Hill near Stonington was established in 1683, and the Schaghticoke Reservation near present day Kent was established in 1736. Paternalistically, the Connecticut Colony (and later the state) appointed overseers to manage all affairs on reservation lands on behalf of the colony.

Under these conditions and as the economy shifted on Native lands in the 18th century from subsistence living to a market economy, substantial cultural changes happened within Native communities and Native families. While cultural values of Connecticut’s Native populations remained intact, much of the Native populations left reservations in search of economic stability not afforded on reservation lands. Connecticut’s Native peoples were becoming intertwined in urban neighborhoods. Whaling proved to be a successful merit-based occupation for Native men in Southern New England. Increasing numbers of Native men left communities for extended periods of time to work on whaling ships. These voyages ranged from months to years. [See “New London’s Indian Mariners,” Spring 2009.] Governance of Native lands remained largely in the hands of the women who occupied the lands year-round.

The population of Connecticut soared in the early 18th century as a result of the profitability of the colonial settler method of extracting the plentiful resources of the new colony. This fueled the need for more land. The Native values of maintaining and sustaining the landscape for the good of all were taken over by English colonial values of private property ownership. There was a near total shift away from the equitable governance of Native land management and the cultural value of land as a maternal force that needed care to a system of colonial “improvement.” Native women faced even more challenges to their ability to lead and maintain the continuity of Connecticut’s reservations. In addition to Mary Momoho and the Eastern Pequot, the story of the Pequot at Noank and Mashantucket illustrates this point well.

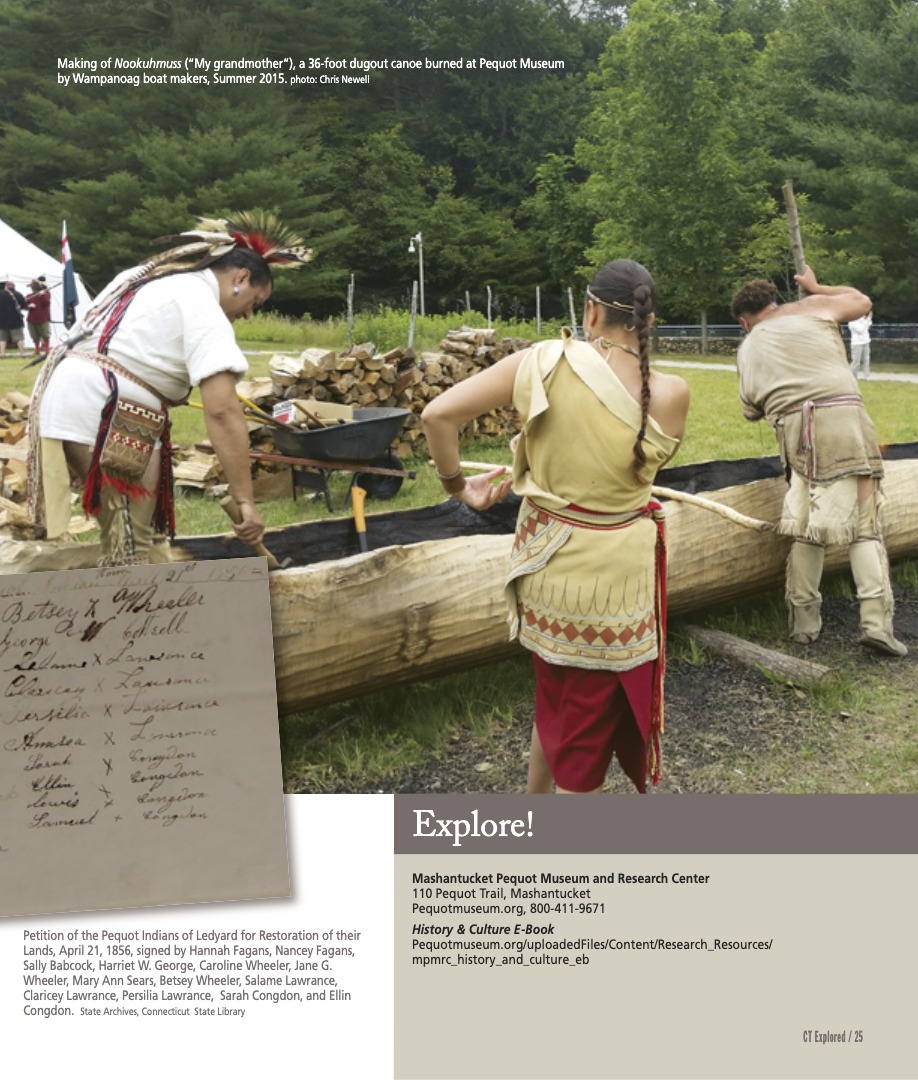

In 1651 John Winthrop Jr., founder of New London and later governor of Connecticut, convinced the Connecticut Colony to establish a 500-acre reservation in Noank for some of the Pequots, and in 1666 the Connecticut General Assembly voted to establish the Mashantucket reservation, which still stands today as the oldest, continuously occupied reservation in the United States. The Pequot Museum’s History & Culture E-book recounts that Pequot land at Noank was divided and allotted to English residents beginning in 1712. Mashantucket saw its original 2,500 acres diminished by encroachment to fewer than 1,000 acres by the end of the 18th century. Under Connecticut statehood, this trend continued. In 1855, based on census records that used arbitrary methods of counting Indians on Connecticut reservations, the Connecticut General Assembly, in violation of federal law, voted to sell approximately 700 acres of the remainder of the Mashantucket Pequot reservation against the will of the tribe, leaving it with only 179 acres. The decision was met with a legal petition by the Mashantucket Pequot community against the sale in 1856. The petition, now in the state archives, lists many complaints about the conditions the Pequot were forced to live under and asserted that this latest devastating blow was a continuation of the grievances of the past. Though the petition refers to the petitioners as “men,” the majority of the signatories on the petition were Mashantucket Pequot women.

In 2020 the United States celebrates 100 years of women’s suffrage. But when the historical perspective is widened beyond hundreds of years to thousands of years, we can see that the cultural history of the land that is now the state of Connecticut has an identity that originates not only with women’s suffrage but also with equity in women’s governance. In this land, the creation stories of the Native cultures create a worldview of land as a female entity that provides life for all of the creatures that dwell upon it with lessons that if it is taken care of properly, the resources will sustain. Settler colonialism upset that life-sustaining balance 400 years ago and imposed the English patriarchal worldview of land and governance. The value of land shifted quickly in that paradigm. In rapid succession, the entire landscape changed and continues to change. The colonial lifeways of ownership and extraction are now built into the culture of American freedom and economy. As America matures, an awakening is beginning to occur. As the current population looks ahead, more and more people realize these lifeways are not sustainable.

In 2020 the United States celebrates 100 years of women’s suffrage. But when the historical perspective is widened beyond hundreds of years to thousands of years, we can see that the cultural history of the land that is now the state of Connecticut has an identity that originates not only with women’s suffrage but also with equity in women’s governance. In this land, the creation stories of the Native cultures create a worldview of land as a female entity that provides life for all of the creatures that dwell upon it with lessons that if it is taken care of properly, the resources will sustain. Settler colonialism upset that life-sustaining balance 400 years ago and imposed the English patriarchal worldview of land and governance. The value of land shifted quickly in that paradigm. In rapid succession, the entire landscape changed and continues to change. The colonial lifeways of ownership and extraction are now built into the culture of American freedom and economy. As America matures, an awakening is beginning to occur. As the current population looks ahead, more and more people realize these lifeways are not sustainable.

As the young country of the United States continues to grow and learn about itself, we increasingly see that the systems created and imposed by America on the land are not keeping pace with the ever-changing needs of our current shared civilization. However, in Native communities and families, where histories exist as living memories in the minds and cultures of the residents, some would say the spirit of the land is reacting to the changes that have been so rapidly imposed, and the hearts and minds of the people of our lands are seeing a change.

It’s been 100 years since the passage of the 19th Amendment. Opening the door for women to vote was the beginning—a great step toward restoring the equity of voice and governance that successfully governed Quinetucket and sustained its resources for thousands of years. In the end, the land will always balance things out, whether human beings are here or not. Let’s pay heed to the success of women’s suffrage and women’s governance and continue to march toward equity so that our society and our succeeding generations relearn the lessons of the land to sustain us all into the future.

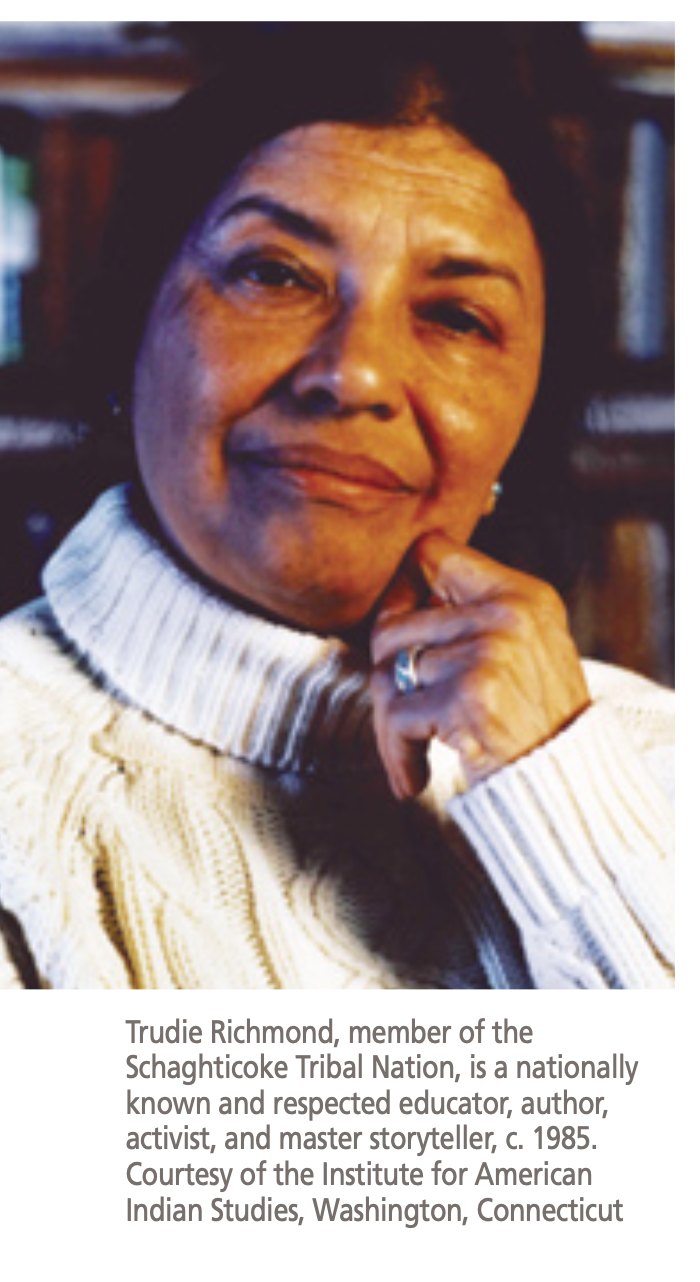

Chris Newell, a citizen of the Passamaquoddy Tribe at Indian Township (Maine), is a co-founder of Akomawt Educational Initiative and former education supervisor at the Mashantucket Pequot Museum. He is currently executive director of the Abbe Museum in Bar Harbor, Maine.

Explore!

Mashantucket Pequot Museum and Research Center

110 Pequot Trail, Mashantucket

Pequotmuseum.org, 800-411-9671

History & Culture E-Book

pequotmuseum.org/uploadedFiles/Content/Research_Resources/mpmrc_history_and_culture_ebook.pdf

“Breaking the Myth of the Unmanaged Landscape,” Spring 2012