By Tobias Glaza and Paul Grant-Costa

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Spring 2012

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

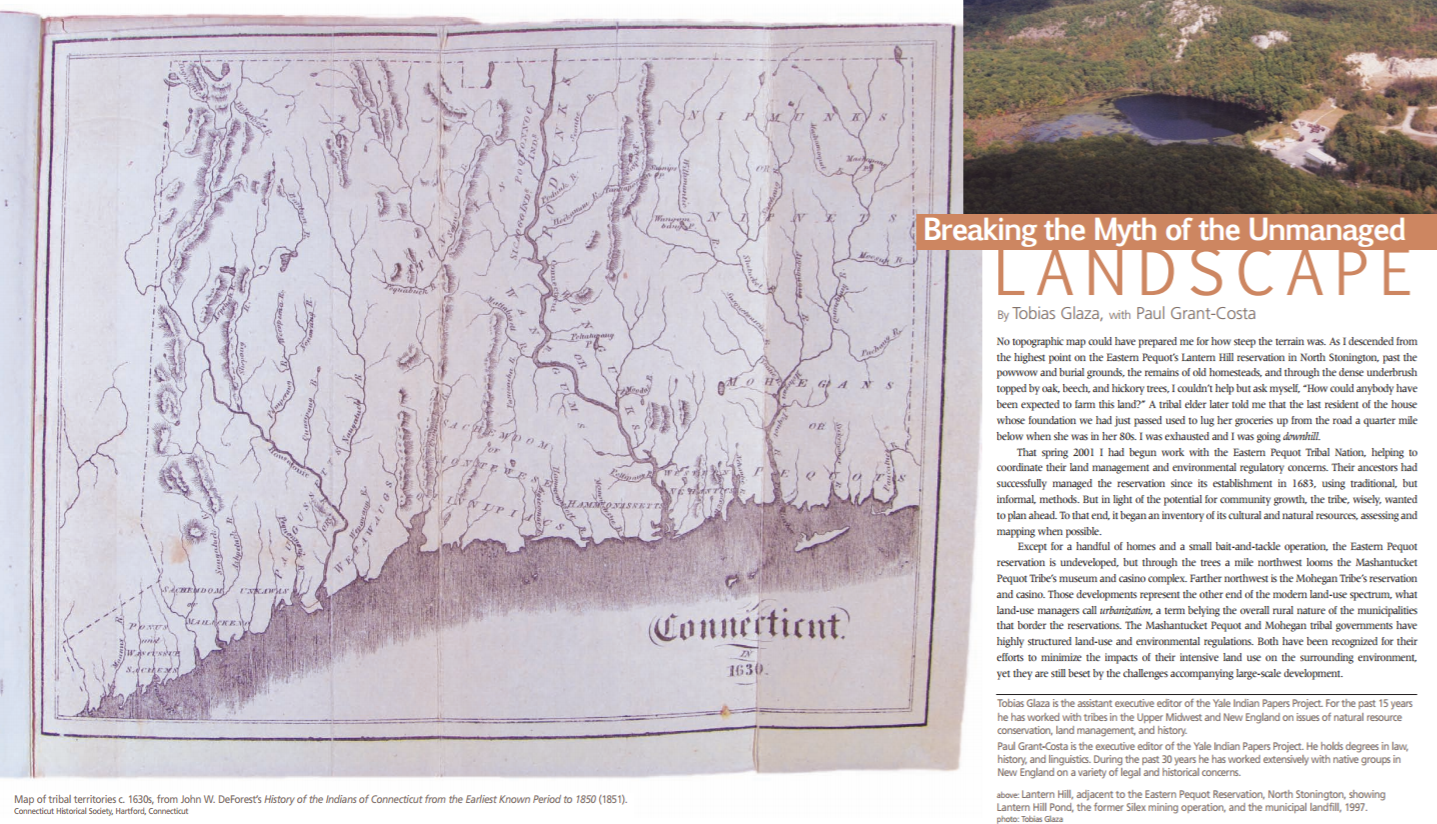

No topographic map could have prepared me for how steep the terrain was. As I descended from the highest point on the Eastern Pequot’s Lantern Hill reservation in North Stonington, past the powwow and burial grounds, the remains of old homesteads, and through the dense underbrush topped by oak, beech, and hickory trees, I couldn’t help but ask myself, “How could anybody have been expected to farm this land?” A tribal elder later told me that the last resident of the house whose foundation we had just passed used to lug her groceries up from the road a quarter mile below when she was in her 80s. I was exhausted and I was going downhill.

That spring 2001 I had begun work with the Eastern Pequot Tribal Nation, helping to coordinate their land management and environmental regulatory concerns. Their ancestors had successfully managed the reservation since its establishment in 1683, using traditional, but informal, methods. But in light of the potential for community growth, the tribe, wisely, wanted to plan ahead. To that end, it began an inventory of its cultural and natural resources, assessing and mapping when possible.

Except for a handful of homes and a small bait-and-tackle operation, the Eastern Pequot reservation is undeveloped, but through the trees a mile northwest looms the Mashantucket Pequot Tribe’s museum and casino complex. Farther northwest is the Mohegan Tribe’s reservation and casino. Those developments represent the other end of the modern land-use spectrum, what land-use managers call urbanization, a term belying the overall rural nature of the municipalities that border the reservations. The Mashantucket Pequot and Mohegan tribal governments have highly structured land-use and environmental regulations. Both have been recognized for their efforts to minimize the impacts of their intensive land use on the surrounding environment, yet they are still beset by the challenges accompanying large-scale development.

Every community requires housing, healthy food, clean water, and places for burial, recreation, and ceremony. The tribes’ continuing challenge has been to meet those needs within the boundaries of a greatly reduced land base and in compliance with complex federal, state, and, in some cases, their own tribal regulatory frameworks. While economic development in the form of gaming has made this somewhat easier for two Connecticut tribes, it remains a challenge for the remaining three tribes in the state: the Golden Hill Paugussett in Colchester and Trumbull, the Schaghticoke in Kent, and the Eastern Pequot in North Stonington.

A SURVEY OF LAND USE OVER 500 YEARS

The Eastern Pequot and other Connecticut tribes recognize that planning for the future requires an examination of the past. What was this land like 50, 100, or 500 years ago? How have traditional native land use and subsistence practices changed over time? What forces instigated these changes?

Asking those questions unearths a history stretching from native communities’ first contact with Europeans to the present. That history is complicated by episodes of disease, warfare, colonialism, and land loss. But it also offers examples of native innovation, adaptation, and persistence. Along the way, a common misperception has gained a foothold in the American consciousness: that the historical Connecticut Indian landscape was an unmanaged wilderness. This could not be farther from the truth.

An extensive archaeological record supports the oral tradition that for approximately 10,000 years, Indians have occupied the land and exploited the associated natural resources within what would eventually become Connecticut. To understand the more recent past ethnohistorians weave archaeology and oral tradition with extensive documentary evidence, the earliest of which are the narratives of European explorers and settlers, to create a detailed record of the highly mobile and adaptive nature of native land use and subsistence patterns.

The importance of agriculture in early Connecticut Native culture was reflected linguistically both in place names and in the construction of its monthly time cycle. For instance, in mid-April and early May, or Squannikesos (which translates to “when they set Indian corn”), Indians quit their winter camps and traveled as far as 60 miles to their farmsteads or summer fields to prepare them for planting. After planting, crops needed less community attention beyond weeding, as the local name for May (Moonesquanimock kesos, “when women weed corn”) indicates. At this time, small bands broke off from the larger community to tend personal gardens near the coast, where they collected seafood and gathered rushes and cattails for making mats.

Coastal people took advantage of marine resources year round, but from March (Namossack kesos, the “fish-catching month”) to June, fish became more active, and Indians moved to the shores of the Connecticut River and the Long Island Sound to take advantage of the seasonal bounty. Many locations still bear the names given to them by the local native communities. More than just quaint reminders of the past, the place names served and, in some cases, still serve, as repositories of traditional ecological knowledge: Quambaug, (which translates to “scoop up fish in cove”) in Stonington and Wabbaquasset (which translates to “mat making place” or “at the place of rushes”) in Woodstock are good examples.

Once the crops began to grow, the first hunting season began. Fishing and fowling supplemented Indians’ food stores, and forests were cleared of underbrush annually through the controlled use of fire.

By the close of August (Micheenee kesos), Indians knew that “the corn had become edible,” as indicated by the English translation. The onset of fall brought the corn harvest and gathering of chestnuts, acorns, and various wild plants. Tree nuts were husked, dried, pounded, and used to thicken broth or porridge. In September (Pohquitaqunk kesos, “the middle between harvest and eating Indian corn”), preparations began for a season of gaming, dancing, feasting, and ceremony. After the harvest celebrations, people stored their surplus corn and beans in grass-lined pits or buried baskets and broke camp for the fall hunt. Their target was larger game—deer, moose, and bear—all at their fattest during the fall—and beaver, valued for their luxurious pelts.

In October (Pepewarr) and November (Quinne kesos), both meaning when “white frost was on the grass and ground,” villagers, except for those hunting parties still at work, began to move inland into the dense forests, what Williams called their “thick warme vallies” and lived there throughout December (Papsapquoho, “the middle of winter”), January, and February. In these cold-weather camps, they ice fished, trapped winter game, and made use of dried provisions. They fashioned and mended equipment and clothing and told tribal stories as passed down by their ancestors. With the end of winter, they began preparing for another annual cycle of life.

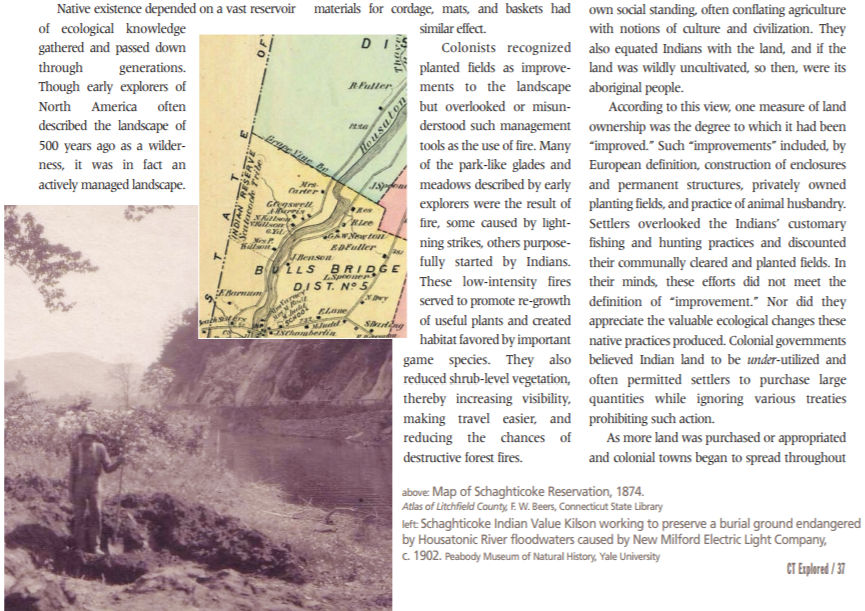

Native existence depended on a vast reservoir of ecological knowledge gathered and passed down through generations. Though early explorers of North America often described the landscape of 500 years ago as a wilderness, it was in fact an actively managed landscape. The land was cleared, irrigated, tilled, pruned, transplanted, selectively harvested (hunted, fished, trapped, and gathered), sowed, weeded, dammed, and burned. These management techniques are human replications of natural disturbances—flooding, wind shear, erosion, and forest fires—but tempered with respect to timing, intensity, and scale. Some portions of the landscape were highly managed, while others benefited from more subtle human interventions. Agriculture and fire, for example, dramatically shape ecosystems, whereas the discrete encouragement of certain woodland plant species is less dramatic, but still important, in terms of overall ecosystem dynamics.

Native existence depended on a vast reservoir of ecological knowledge gathered and passed down through generations. Though early explorers of North America often described the landscape of 500 years ago as a wilderness, it was in fact an actively managed landscape. The land was cleared, irrigated, tilled, pruned, transplanted, selectively harvested (hunted, fished, trapped, and gathered), sowed, weeded, dammed, and burned. These management techniques are human replications of natural disturbances—flooding, wind shear, erosion, and forest fires—but tempered with respect to timing, intensity, and scale. Some portions of the landscape were highly managed, while others benefited from more subtle human interventions. Agriculture and fire, for example, dramatically shape ecosystems, whereas the discrete encouragement of certain woodland plant species is less dramatic, but still important, in terms of overall ecosystem dynamics.

Indians abandoned communal and family fields in a particular location once nutrients had been depleted from the soil and cleared new fields, creating, over generations, a patchwork of habitats and increasing biological diversity. It is likely that repetitive and intensive harvest of firewood and materials for cordage, mats, and baskets had similar effect.

Colonists recognized planted fields as improvements to the landscape but overlooked or misunderstood such management tools as the use of fire. Many of the park-like glades and meadows described by early explorers were the result of fire, some caused by lightning strikes, others purposefully started by Indians. These low-intensity fires served to promote re-growth of useful plants and created habitat favored by important game species. They also reduced shrub-level vegetation, thereby increasing visibility, making travel easier, and reducing the chances of destructive forest fires.

Contemporary land managers have begun to accept what native people have known for years: Humans are an integral part of the larger ecological equation and sustainable harvest and land-use practices contribute to an ecosystem’s overall health and biodiversity.

THE IMPACT OF EUROPEAN SETTLEMENT

In 1600, before European settlement, Connecticut’s Indian population reached nearly 60,000. A generation later, a series of Europeanborne epidemics reduced this number by 90 percent, leaving about 5,400 native people, with a shattered social and economic structure, to face the brunt of colonization.

Indian land in Connecticut was acquired by European settlers through colonial conquest and by purchase, often by unscrupulous land speculators. Colonists used their observations of the physical world to justify legal conclusions about land ownership and the primacy of their own social standing, often conflating agriculture with notions of culture and civilization. They also equated Indians with the land, and if the land was wildly uncultivated, so then, were its aboriginal people.

According to this view, one measure of land ownership was the degree to which it had been “improved.” Such “improvements” included, by European definition, construction of enclosures and permanent structures, privately owned planting fields, and practice of animal husbandry. Settlers overlooked the Indians’ customary fishing and hunting practices and discounted their communally cleared and planted fields. In their minds, these efforts did not meet the definition of “improvement.” Nor did they appreciate the valuable ecological changes these native practices produced. Colonial governments believed Indian land to be under-utilized and often permitted settlers to purchase large quantities while ignoring various treaties prohibiting such action.

As more land was purchased or appropriated and colonial towns began to spread throughout Connecticut, Indians were no longer free to use the land as they had been accustomed. While their moving from site to site was viewed by colonists with apprehension, especially during times of war, the reality was that the scope of colonial settlements—houses, barns, outbuildings, and fenced fields and pastures— not only limited native access to traditional hunting, fishing, gathering, and ceremonial sites but also restricted where Indians could permanently settle.

During colonial times guardians were appointed by the general assembly to informally assist the tribes. The state later formalized the process, instituting an overseer system under which Indians living within tribal reservations were considered its wards, with governmental agencies making decisions about their property and activities. Frequently the General Assembly granted away the best of native property to colonial families, reserving or sequestering small sections of poorer quality lands for its remaining Indian populations. The state ceded lands including homesteads, fields, pastures, and, to the great consternation of the Indians, burial grounds. Such was the case with the Niantic at Black Point, Mohegan in Norwich, and both Pequot tribes with lands in Noank and Ledyard, to name only a few.

And, too often, colonists continued to encroach even on sequestered Indian lands, fencing them in, clearing and planting, removing timber, and allowing wayward livestock to damage crops. Tribes vigorously resisted, often channeling their protests through advocates appointed by the colony. The colony contended that these reservations still fell within their jurisdiction and maintained that they had the right to further reduce the lands or move the tribes to other areas as they saw fit. When lands were taken or new boundaries were imposed, the tribes sought redress with petitions to the courts, the General Assembly, and even the English crown.

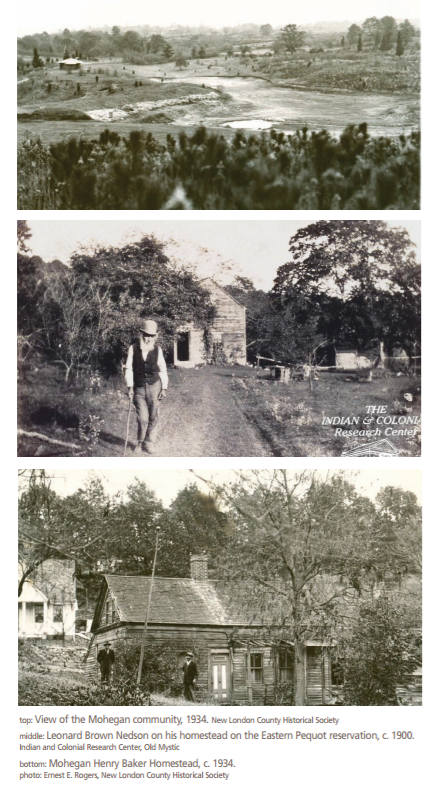

Try as they might, by the mid-1700s colonial policies had reduced Indian lands to a fraction of their original size. With the establishment of permanent reservations, the tribes’ ability to move throughout the region to access specialized habitats and engage in traditional subsistence activities was further reduced. Documentary and archaeological evidence reveals a shift from construction of traditional wigwams to framed houses as their lifestyle became more sedentary. Extended hunting trips occurred less frequently, marine resources became more difficult to access, and animal husbandry, specifically the keeping of pigs, chickens, and, occasionally, larger draft animals, was introduced on the reservations.

Esther Beaumont, c. 1890. Beaumont was an itinerant basket maker born to a Narragansett father and a Connecticut Native American woman who eventually settled in Durham. She was representative of a growing demographic of Connecticut Indians in the late 19th century who lived outside of tribal relations. This mobility was especially common for basket makers who traveled a circuit selling their wares. Collection of Francis E. Korn, Durham Town Historian

Not surprisingly, the nature of Indian agriculture began to change. Tribes adopted many Euro-American agricultural practices but did not abandon their traditional ways altogether. Francisco de Miranda, a prominent Venezuelan revolutionary touring the United States, noted in his diary in 1783 that the Mohegan still planted their corn in the Indian manner “with neither circles nor any divisions.” But as their respective land bases continued to diminish in the 18th and 19th centuries, so did their access to arable land. This was certainly true of the Schaghticoke, Paugussett, Mashantucket, and Eastern Pequot, whose reservations were either extremely small or rocky, or both. Tribal populations continued to decrease as men and women left the reservations to seek employment as soldiers, whalers, day laborers, or domestics. Shortly after the American Revolution and for several years afterward, portions of these communities migrated to New York and, later, Wisconsin, as part of the Brothertown Indian Movement, an agrarian Christian community.

The decreasing on-reservation populations and marginal quality land resulted in fewer communal fields and an increased reliance on the small home garden for food, medicine, and other needs. These gardens may also have had overlapping functions, serving as part of the range for pigs and chickens and as processing and social areas. During an 1852 visit, historian John Deforest commented that, “one acre would include all that is cultivated by the Pequots, who can not be induced to till anymore than will serve for their garden spots.” Four years later, a state-appointed committee noted that “a very small portion of the land is cultivated by the tribe—each family improves what might be denominated a garden.” During the 19th century and first half of the 20th century the produce from these gardens was an important part of the household economy.

Some older traditions endured. Indians continued to harvest black ash, white oak, and other materials for making baskets, brooms, and spoons for their own use and to sell. The harvesting of these materials occasionally resulted in conflict with neighboring non-natives who disputed the Indians’ right to gather from off-reservation lands. This cottage industry supplemented the meager allowance the State of Connecticut granted to each Indian family. The allowances were drawn from a tribal fund that was generated from the sale and leasing of reservation land and the sale of timber and firewood, transactions that often incited tribal protest.

Beginning in the early 1900s oversight of the tribes and the management of their lands moved to the Parks and Forest Commission, then to the Welfare Department, and finally to the Department of Environmental Protection (DEP). In the 1970s Indians in Connecticut gained more political power with the formation of the Indian Affairs Council (IAC) made up of representatives of the five Connecticut tribes and officials from DEP. Through the IAC the tribes had a larger voice in the management of their respective reservations. Current land-use issues on Connecticut’s Indian reservations can be complicated by overlapping jurisdictions and internal tribal disputes. Successfully negotiating federal, state, and municipal concerns while asserting sovereignty is fraught with legal complexities and requires sophistication and diplomacy.

Many Connecticut Native Americans still live, work on, and derive sustenance from ancestral lands. The manner in which they do this may have changed, but traditional ways co-exist with new practices. Hunting, fishing, and gathering, along with small-scale horticulture, remain part of their management repertoire, but the tribes have also embraced modern technologies and techniques for managing their lands. A shared interest in protecting and preserving natural and cultural resources has led to a number of collaborations between the tribes and academic  institutions and federal and state agencies. Elders and archaeologists work together to identify and protect important cultural resources. Using non-invasive ground-penetrating radar, they have been able to locate, identify, and protect previously unknown burial grounds and other culturally significant archaeological sites on their tribal lands. Tribal land managers, together with state and federal partners, use a combination of oral tradition, historic maps, on-the-ground monitoring, and aerial or satellite imagery to identify changes in the landscape (such as areas where illegal dumping has occurred and threats to critical water supplies) or for locating habitat suitable for the re-establishment of black ash. These collaborations have enhanced the tribes’ land-use and management efforts in ways that would have been difficult to imagine 40 years ago and have led to more informed decision-making.

institutions and federal and state agencies. Elders and archaeologists work together to identify and protect important cultural resources. Using non-invasive ground-penetrating radar, they have been able to locate, identify, and protect previously unknown burial grounds and other culturally significant archaeological sites on their tribal lands. Tribal land managers, together with state and federal partners, use a combination of oral tradition, historic maps, on-the-ground monitoring, and aerial or satellite imagery to identify changes in the landscape (such as areas where illegal dumping has occurred and threats to critical water supplies) or for locating habitat suitable for the re-establishment of black ash. These collaborations have enhanced the tribes’ land-use and management efforts in ways that would have been difficult to imagine 40 years ago and have led to more informed decision-making.