By Christopher Pagliuco

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. FALL 2008

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

In the late 19th century, the piano seemed to be everywhere, from genteel parlors to working-class saloons. It was a stock prop in many of the prominent literary works of Charles Dickens, Jane Austen, Mark Twain, and other writers of the day. Piano virtuosos such as Arthur Rubinstein and Ignacy Paderewski played to worshipful crowds of thousands. In the saloons, men and women drank and danced to the rapid beat of the “Maple Leaf Rag” pounded out on the keyboard. In the evenings, families sang to the accompaniment of the piano in their parlor, and young women were courted on the piano bench.

The piano was intimately wove into the lives of Victorians, and two Connecticut companies, Comstock, Cheney and the Company of Ivoryton and Pratt, Read and Company of Deep River, provided the vast majority of pianos’ smooth elephant ivory keys. At the height of their business in 1910, more than 90 percent of the ivory imported from East Africa into the United States was processed in Ivoryton primarily for the production of ivory piano keys in Ivoryton and Deep River. The rise and decline of the piano and of the ivory trade-and one of those companies in particular, Comstock, Cheney and Company- made indelible marks on the region’s community and culture.

The piano was intimately wove into the lives of Victorians, and two Connecticut companies, Comstock, Cheney and the Company of Ivoryton and Pratt, Read and Company of Deep River, provided the vast majority of pianos’ smooth elephant ivory keys. At the height of their business in 1910, more than 90 percent of the ivory imported from East Africa into the United States was processed in Ivoryton primarily for the production of ivory piano keys in Ivoryton and Deep River. The rise and decline of the piano and of the ivory trade-and one of those companies in particular, Comstock, Cheney and Company- made indelible marks on the region’s community and culture.

As late as 1850, the western portion of Essex that was later to be named Ivoryton was a rural farming community consisting of little more than two dozen insignificant buildings owned by fewer than five families. It remained that way until Samuel Merritt Comstock, a native of Essex, following in the footsteps of other, more famous Connecticut entrepreneurs such as Samuel Colt and Eli Whitney, started a company that would transform the town and employ more than 900 workers.

As industrialization gained speed during the 19th century, society adopted a new urban lifestyle. Along with that came changing moral standards, shifting social classes, and a new style of business relationship that was increasingly impersonal. In response, as America made a wrenching transition from an agricultural to an industrial society, new social movements developed to ease the resulting anxiety. Surprisingly, many featured the piano.

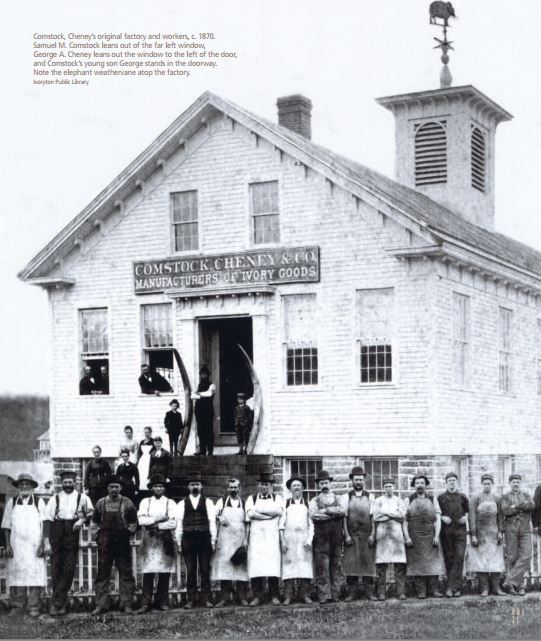

Comstock seized the opportunities these changes presented. Comstock began his career in 1834 in a shop that made screwdrivers. In 1847, he set out on his own, founding the S.M. Comstock and Co., which made items such as toothpicks, combs, and billiard balls from ivory. Manufacturing of such objects had been underway in Connecticut for at least 20 years. Julius Pratt of Meriden received patents in 1828 and 1830 for an ivory slitting machine and a method of making combs, respectively. In the 1830s, Pratt was also supplying cutlery manufacturers with ivory for handles. (Sometime after 1873, Pratt moved his operation from Meriden to Deep River, becoming Comstock’s chief competitor.) Comstock greatly expanded his comb-making business, developed machines to mechanize, and rationalized production. Both Comstock and Pratt’s businesses prospered, and they began manufacturing piano keys and other parts for pianos. By 1909, decades after Comstock’s death, the successor company, Comstock, Cheney, and Co., together with its local rival, Pratt, Read and Company, produced more than 390,000 piano keyboards and actions (the mechanism that turns a key stroke into sound), serving every major piano brand in the country. (Today, about 50,000 pianos are sold annually in the United States.)

At the time of Comstock’s birth in 1809, the small town of Essex was dominated by shipbuilding on the banks of the Connecticut River. Between 1785 and 1860, 545 ships were constructed in Essex. With the advent of mills powered by rivers in the early 19th century, the economic future of Essex developed inland, as manufacturers located their operations along the banks of the Falls River. Shipbuilding along the Connecticut River waterfront went into decline.

At the time of Comstock’s birth in 1809, the small town of Essex was dominated by shipbuilding on the banks of the Connecticut River. Between 1785 and 1860, 545 ships were constructed in Essex. With the advent of mills powered by rivers in the early 19th century, the economic future of Essex developed inland, as manufacturers located their operations along the banks of the Falls River. Shipbuilding along the Connecticut River waterfront went into decline.

In 1862 Comstock sold a portion of his company to George A. Cheney, forming a partnership and renaming the company Comstock, Cheney and Company. The new firm combined Comstock’s mechanical mind with Cheney’s keen entrepreneurial acuity. Harnessing the water power from live reservoirs enabled Comstock, Cheney and Co., to operate year round and process between eights thousand and nine thousand pounds of ivory a month, a rate so prodigous that the piano key factories in Ivortyon and Deep River came to dominate the East African ivory trade.

The ivory trade from the late 18th to the early 20th centyre was fueled by the severe exploitation of African resources and the enslavement and death of as many as a million African tribespeople. Undoubtedly the robust business conducted by Pratt, Read and Comstock, Cheney and Company contributed to that tragedy. Ivory was the perfect material for piano keys. Unlike the exotic wood veneers previously used for piano keys, ivory maintained the ideal temperature, texture, and density to respond to the pianist’s touch. Only when the ivory trade was banned in the 1950s to protect near-decimated elephant populations were ivory keys replaced by plastic. Anne Farrow, Joel Land, and Jenifer Frank’s Complicity (The Hartford Current Company, 2005) describes the African ivory trade in detail. Complicity notes that at its core, it came to this: pack animals could not be used to transport the tusks-some as heavy as 80 pounds-because they were not immune to the deadly tsetse fly. Human slaves were substituted, carrying tusks as far as 1,000 miles to port where both slave and tusk were sold.

The Piano’s Rise to Victorian Prominence

According to piano historian Cyril Eherlich, “the expansion of the American piano industry after 1865 is without parallel.” By 1900 more than half of the world’s pianos were made in the U.S. In 1910, piano production in the United States was growing at a rate six times faster than the population. What accounts for such strong demand? Ironically, it was the increasing social ills strongly associated with the very growth of factories like Comstock, Cheney and Company. Craig H. Roell, author of The Piano in America, 1890-1940, (University of North Carolina Press, 1989) explains that the piano industry was “morally, socially, and financially buttressed by the Victorian ethos…” and describes chronologically the many social movements featuring the piano. Music, he notes, was hailed by reformers as a tool to counteract the manipulation, selfishness, degrading treatment, and monotonous work associated with factory labor and to stem the deterioration of moral order during that turbulent era. Roell emphasizes this belief that music “…could rescue the distraught from the trials of life. Its moral restorative qualities could counteract the ill effects of money, anxiety, hatred, intrigue, and enterprise.”

As early as the 1830s, a movement for the mandatory instruction of music in public education began and continued well into the 20th century. In the 1920s, Etude magazine published “The Golden Hour Plan,” which advocated for music education as a means of character development. According to the plan, “The key was to reach children with music before they were contaminated by modern society.”

The “Cult of Domesticity” was another social movement with the piano at its center. The Victorian home, with its architecturally ornate turrets and nooks, was designed to serve as a sanctuary from the evils of a commercial society maintained by the wide and/or mother of the household. Mary Burgan, in Heroines at the Piano: Women and Music in Nineteenth Century Literature (Indiana University Press, 1989), asserts, “Of all the luxuries available to the middle classes in 19th century England, the piano was perhaps the most significant in the lives of women; it was not only an emblem of social status, it provided a gauge of a woman’s training in the required accomplishments of genteel society.” Mass production, coupled with the new space-saving design of the upright piano, made the piano more accessible for middle-class families, further increasing demand.

During this period, the middle class seeking respectability was urged to turn away from the vice-filled streets for entertainment and enjoy recreation within the safe confines of the home. Singing and dancing to the piano in the evening, most frequently with a female on the bench, became a common amusement for the family. Not surprisingly, music was associated with Victorian courtship, and images of couples swaying on a piano bench, arms intertwined, became iconic.

Ironically, the piano found favor in saloons and brothels in just those streets respectable people were supposed to avoid. In the public sphere, Scott Joplin’s 1899 “Maple Leaf Rag” popularized Ragtime, a new type of music that matched the new fast pace of life. Although it was shunned at first, Ragtime became popular between 1900 and 1920. Perhaps riding Ragtime’s wave, Comstock, Cheney, and Company sold more pianos in 1909 than in any other year.

During World War I, the U.S. government deemed piano-making an essential industry, thereby ensuring the availability of production materials. Shortly thereafter, during the “Music in Industry” movement (in which the perceived mental, emotional, and physical benefits of music were used to counteract the dehumanizing aspects of the industrial assembly-line work), attempts were made to use the piano and singing groups to break up the monotonous work of the assembly line and increase productivity. These efforts were effective; one study revealed a 6 percent increase in average per-worker output and a 34 percent decrease in absenteeism when the power of music was harnessed in the workplace.

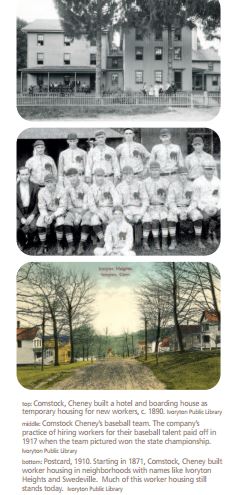

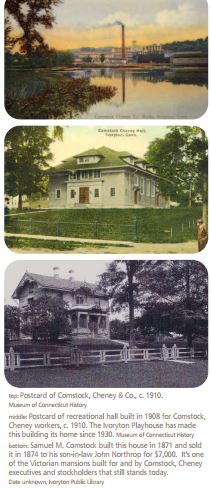

These movements and other ensured a booming business for Comstock, Cheney, and Co. By 1873 a second factory was necessary and was built further up the Falls River. Comstock had the rare opportunity to build the village of Ivoryton according to his own design. Comstock sold his land along Ivoryton’s wide main thoroughfare to his executives and stockholders to build the ornate Victorian mansions that he favored and are still seen there today. Early in the 1860s the company had built a hotel and boardinghouse as temporary housing for new workers. Comstock, Cheney began building company housing to rent and sometimes mortgage to employees. Beginning in 1871 and continuing over the next 50 years, the company built, financed, or otherwise encouraged the construction of more than 130 houses, an extraordinary number for such a small village. These houses were apportioned out to workers based on ethnicity, with neighborhoods called Swedenville, Little Italy, and Polack Town. In 1873, a village general store was built in the center of town with a banquet hall on the second floor for town graduations and other events. As one of the only easily accessibnle stores in town, known for years as the Rose Brothers Store though it was owned by Comstock, Cheney, the store provided workers with life’s daily essentials-and the company with further profits. (The banquet room was replaced in 1911 with a larger company hall, now the Ivoryton playhouse.)

These movements and other ensured a booming business for Comstock, Cheney, and Co. By 1873 a second factory was necessary and was built further up the Falls River. Comstock had the rare opportunity to build the village of Ivoryton according to his own design. Comstock sold his land along Ivoryton’s wide main thoroughfare to his executives and stockholders to build the ornate Victorian mansions that he favored and are still seen there today. Early in the 1860s the company had built a hotel and boardinghouse as temporary housing for new workers. Comstock, Cheney began building company housing to rent and sometimes mortgage to employees. Beginning in 1871 and continuing over the next 50 years, the company built, financed, or otherwise encouraged the construction of more than 130 houses, an extraordinary number for such a small village. These houses were apportioned out to workers based on ethnicity, with neighborhoods called Swedenville, Little Italy, and Polack Town. In 1873, a village general store was built in the center of town with a banquet hall on the second floor for town graduations and other events. As one of the only easily accessibnle stores in town, known for years as the Rose Brothers Store though it was owned by Comstock, Cheney, the store provided workers with life’s daily essentials-and the company with further profits. (The banquet room was replaced in 1911 with a larger company hall, now the Ivoryton playhouse.)

As a Business Evolves, So Does a Town

Comstock knew every aspect of the production process and could fraternize comfortable with his employees. In Beer’s History of the Town of Essex, published in 1885, Comstock is described as “…large hearted, liberal, and generous… He was kind and considerate to his employees… When the labors of the day were completed, he engaged heartily in the sports of the men and took an active interest in everything that concerned their welfare or happiness.” Essex town historian Don Malcarne refers to the personal nature of Comstock’s strategy as president of the company as “familial paternalism”.

But upon Comstock’s death in 1878, leadership of the company was transferred to his partner George Cheney. Cheney, a native of New Hampshire, was an entrepreneur who was never as intimately involved in the company as Comstock. After becoming company president, Cheney maintained his primary residence in downtown Essex rather than in Ivoryton.

Before teaming up with Comstock in 1860 Cheney had spent 12 years in Zanzibar, the center of the East African ivory trade, as an ivory trader for his soon-to-be father-in-law. With Cheney’s business acumen guiding it, the company continued to prosper. “Under George Cheney,” Malcarne explains, “the factor was being run in a far more impersonal method of management. The market place was more turbulent, [and]consumer based.” Malcarne adds that “The possibility of unionism and fracturing of the workforce” presented growing challenges for the company.

Cheney developed new strategies in advancing Comstock’s plan for Ivoryton as a town built around the factories, its streets lined with Victorian structures, its neighborhoods divided into ethnic sections, it residents treated to socially reforming entertainment. The company kept an agent in New York to funnel immigrants to meet the factories’ growing labor requirements. As the immigrants arrived from Sweden, Italy, and Poland, Cheney, and later Robert H. Comstock, Samuel’s son, exercised a form of social control over the workforce.

Unlike neighboring Deep River, which had a more diverse economy, Comstock, Cheney was the only substantial employer in Ivoryton, making it a typical company town. For a time, as the village’s sole employer, largest taxpayer (accounting for approximately 35 percent of the town’s tax revenue), and largest real estate holder, Comstock, Cheney wielded almost complete control over the workers’ lives and community.

During the Gilded Age, a period characterized by confrontational labor relations, Comstock, Cheney was able to stave off the formation of labor unions through a practice called welfare capitalism. Under this business strategy, companies made selective investments in the local community in the hope of counteracting labor unrest caused by low wages and employees’ lack of control over their own lives. Such philanthropies also significantly increased productivity and decreased absenteeism among the workforce. This “welfare capitalism” system was successfully employed by Comstock, Cheney until the onset of the Great Depression. The company didn’t need highly educated employees; just well-behaved, reliable workers.

Beyond creating factory housing, Comstock, Cheney and Company financed the construction of, and many times retained control over, many other buildings in town. In 1889, the Ivoryton library was established with a thousand-dollar gift and land donated by the Comstock family. All six library officers maintained close ties to the company, and S.M. Comstock’s granddaughters ran it on a day-to-day basis.

One common practice of welfare capitalist’s was to create constructive opportunities for workers to socialize in an effort to reduce the amount of time spent at the saloon. In Ivoryton, a “wheel club” was established to provide for bowling, bicycling, a band and other social activities. In 1886, a competitive baseball team was established, along with a new ballpark, which still is used by the town today. (One pitcher, Paul Hopkins, who also played for the Deep River team, went on to pitch for the Washington Senators in the major leagues. Although an outstanding player, he is primarily known for giving up Babe Ruth’s 59th home run in the year Ruth his 60 homers.) Over time, Comstock, Cheney, and Company began to hire workers for their baseball talent as opposed to their mechanical skills.

As Victorian values were supplanted by the consumerism of the 20th century, the market for pianos slowly declined from its height in 1910. New entertainment alternatives such as the phonograph, radio and motion picture chipped away at piano sales. Like all businesses during the Depression, Comstock, Cheney struggled to maintain solvency; the company merged with rival Pratt, Read and Co. in 1936. All company keyboard and piano action construction was moved to the Ivoryton factories. By 1959, following the national trend in which companies relocated to southern states where labor was less expensive, the company moved about half of its keyboard and action manufacturing to the town of Central, South Carolina. Production in Connecticut ceased entirely in the late 1980s.

As Victorian values were supplanted by the consumerism of the 20th century, the market for pianos slowly declined from its height in 1910. New entertainment alternatives such as the phonograph, radio and motion picture chipped away at piano sales. Like all businesses during the Depression, Comstock, Cheney struggled to maintain solvency; the company merged with rival Pratt, Read and Co. in 1936. All company keyboard and piano action construction was moved to the Ivoryton factories. By 1959, following the national trend in which companies relocated to southern states where labor was less expensive, the company moved about half of its keyboard and action manufacturing to the town of Central, South Carolina. Production in Connecticut ceased entirely in the late 1980s.

Ivoryton was the only town in the century with that name. It’s a testimony to the central role the lower Connecticut River Valley once played in piano keyboard and action production and a reminder of the international ivory trade’s tragic cost. With the loss nearly three decades ago of the industry that supported the company town, Ivoryton has been challenged to adapt to 21st century realities. The blueprint Comstock envisioned may soon enjoy a renaissance. Developers are proposing mixed-use plans at at least one of Comstock’s two factories. Falls River is now appreciated more as a natural resource than a source of mill power. Walking trails were recently constructed along its banks around the factories. The Copper Beech Inn, formerly the house of Comstock’s son, is adding ten rooms, and the Rose Brothers store is being renovated and will soon be rented. The library and Ivoryton Playhouse are thriving. Comstock’s original villagette concept may be updated to offer as rewarding a lifestyle for residents in the 21st century as it did in the 19th-though with more democratic governance.

Explore!

Taftville: “A Strike Transforms a Village,” Winter 2019-2020

“Cheney Brothers: Innovation in Silk,” Spring 2005