(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Winter 2019-2020

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

The village of Taftville in Norwich underwent a dramatic change in a five-year period from 1875 to 1880. Irish brogues were almost completely replaced by the lilt of French voices after a strike at the Ponemah Mill.

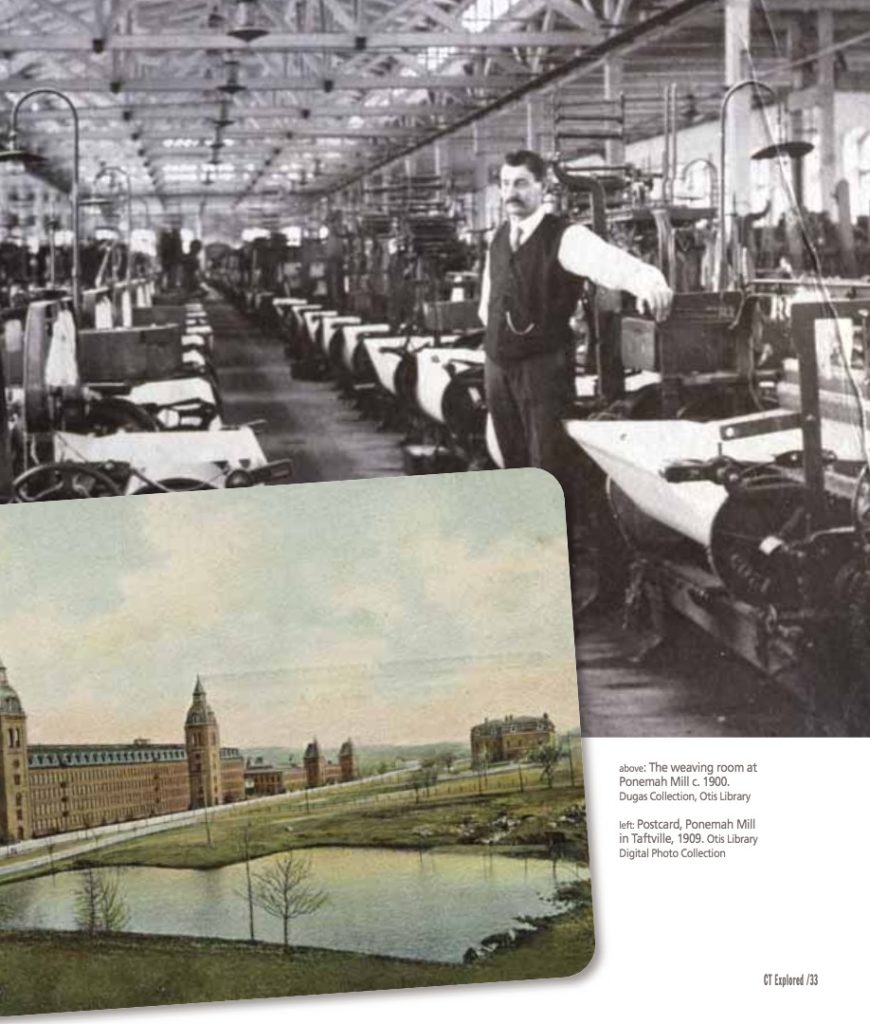

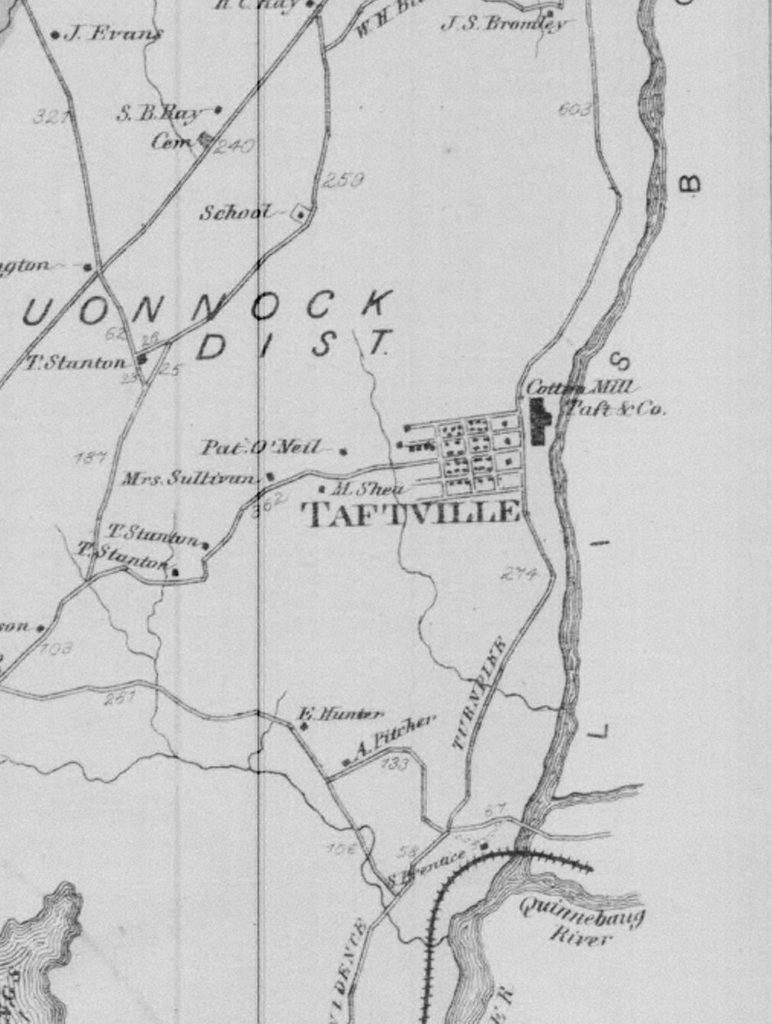

Taftville was founded in 1865 when brothers Cyrus and Edward P. Taft of Providence, Rhode Island bought 600 acres of farm land and water rights along the Shetucket River in the northeast section of Norwich. Once the mill was built, everything the workers needed was established nearby: stores, medical care, social activities, and churches.

According to John D. Nolan’s History of Taftville, Connecticut (Norwich Bulletin, 1940), the Orray Taft Manufacturing Company was chartered on June 19, 1867. James S. Atwood of Plainfield and Moses Pierce of Norwich joined the Taft brothers as the original incorporators, according to the company charter. The four men came from families with considerable manufacturing experience.

The Tafts apparently provided the money, and Pierce advised. Atwood, an engineer, oversaw the project. Atwood began his career as a bobbin boy in his father’s mills, working his way up to management (albeit more rapidly than the average mill hand).

Construction on the 750-foot, five-story mill building began in 1867. The construction workers were largely Irish men, many of whom were veterans of the Civil War. For temporary housing, they erected shanties for themselves and their families.

In late 1867 the Tafts ran out of money and construction halted with the second floor barely completed. A group of investors came to the rescue with an infusion of capital totaling $1.5 million. In 1869 the company was reorganized, and in 1871 the name changed to Ponemah Mill, taken from Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s poem Song of Hiawatha, according to a historical marker in the village.

The new investors also had ties to manufacturing or related enterprises, often in association with one another. Heading the group was Norwich resident John F. Slater, who had been running the family’s Connecticut mills since he was 21 years old. His uncle Samuel Slater was widely recognized as “the Father of American Manufacturers,” a title President Andrew Jackson is said to have bestowed during an 1833 visit to Rhode Island. Slater’s brother William, who owned the family mills in Rhode Island, was an investor, along with Lorenzo Blackstone, a Norwich merchant who owned cotton mills in Killingly and Montville. John Slater was named president, and Edward Taft was named treasurer. James Atwood was the agent, in charge of the mill’s daily operations.

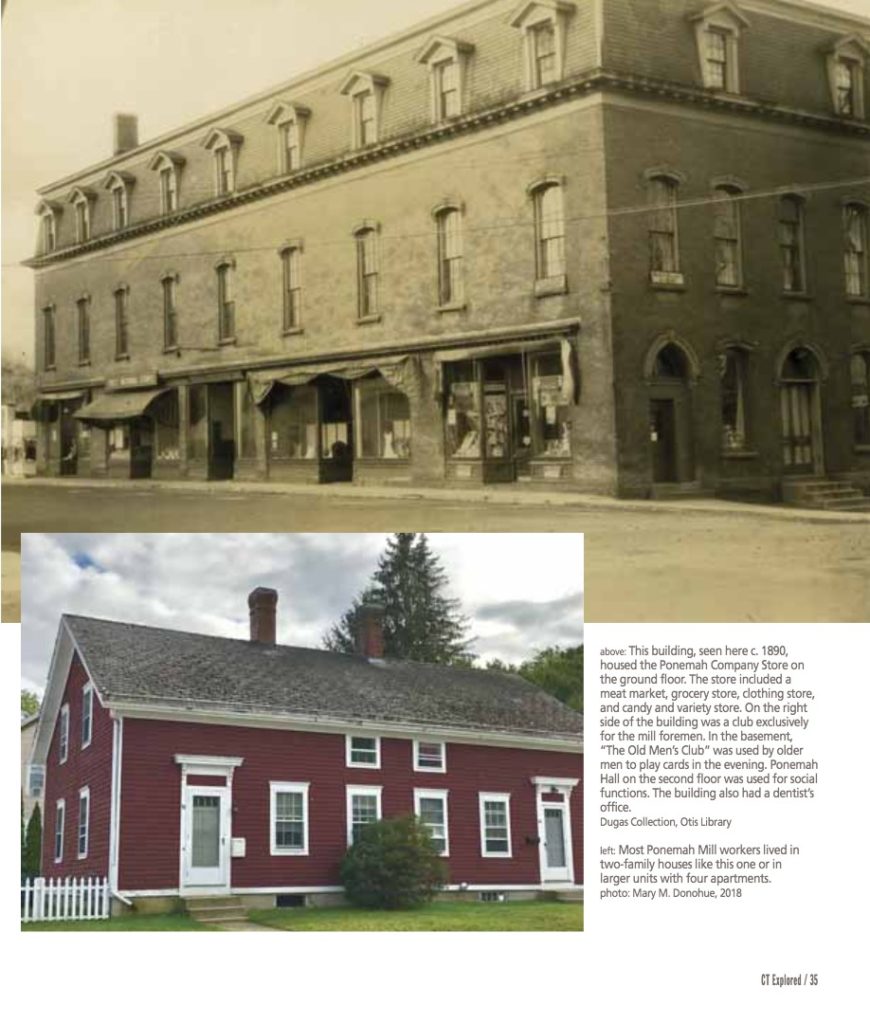

With this influx of money, the mill was completed and the shanties were replaced with 254 two-family houses, each with a yard enclosed by a white picket fence. Unmarried workers—from the mill superintendent down to the lowest factory hand—lived in the company boarding house.

Once operational, Ponemah rapidly became recognized for the high-quality cotton cloth it produced. Its investors rode the crest of the wave that was the post-Civil War expansion—much of it fueled by the national drive to complete a transcontinental railroad. But speculation led to large investments that couldn’t be sustained, and by 1873 the country was plummeted into a full-blown depression as large banking firms failed, causing a chain reaction that led to the failure of local banks.

The directors kept Ponemah running by producing coarser cloth that brought a lower price, which became a justification for reducing wages by as much as 12 percent. Before the end of 1874, they shortened the mill’s hours of operation. Wages were cut another 12 percent on January 1, 1875.

By then the wages for most skilled workers, such as spinners and weavers, had dropped to $8 to $9 for a 67-hour work week—nearly 12 hours a day, Monday through Friday, and 8 and a quarter hours on Saturday. Unskilled mill hands were paid considerably less, and some of the youngest might earn only a few cents a day for the same long hours their parents worked. While Ponemah workers had food and shelter that many others lacked, the way they were paid rankled. Every month, the company store handed out pay envelopes containing whatever sum was left after deductions for rent and food purchased at the company store. Sometimes the envelope contained less than a dollar out of a month’s wages; sometimes it was empty.

Despite the depression, the economics were considerably different for the mill owners. John Slater’s annual income in 1875 was $71,700, according to a list of wealthy Norwich residents and their taxable income in The Hartford Daily Courant, February 16, 1875, and Lorenzo Blackstone’s income was $41,000. The 1870 census, which listed real and personal property, showed Slater’s combined assets totaled more than $1.7 million, while Blackstone’s assets exceeded $800,000. With revenue totaling $836,775 in 1875, the mill remained profitable despite the depression, strongly suggesting that financial peril was not the real reason for cutting wages.

An uptick in the price of manufactured goods in March 1875 prompted a group representing the weavers, spinners, carders, and others to visit mill superintendent William Tucker in early April, seeking a raise. He consulted with Atwood and Taft, “and an increase of 8 to 12 per cent was cheerfully conceded,” stated the Norwich Bulletin months later, on June 10, 1875. This excluded some workers whose wages already matched those paid at other mills. Notices about the forthcoming raise were posted throughout the mill.

On April 7 the mill workers left as usual for dinner at noon, but when the bell rang for the afternoon shift, no one returned. Contrary to what might have been expected after the agreement to increase wages, a strike was on.

John Nolan, a longtime resident, was 11 years old at the time of the strike. In his History of Taftville, he recalled the strikers’ march through town to “the ledge,” an elevated area at the end of North B Street that was a popular picnic ground and gathering area.

John Nolan, a longtime resident, was 11 years old at the time of the strike. In his History of Taftville, he recalled the strikers’ march through town to “the ledge,” an elevated area at the end of North B Street that was a popular picnic ground and gathering area.

Nearly every afternoon the strikers marched to the ledge—and several fiery speakers addressed the crowd, the band took up their duties. There were a few musical instruments, but the majority was equipped with boilers, tin pans, etc. and the din was indescribable …

The speakers were apparently outside agitators. Nolan suggested they were affiliated with the Knights of Labor, which had an office in Kelly’s Hall on Merchants Avenue. The Bulletin’s June story reported, “It was probably through the influence of gentlemen from Fall River, agitators, born and bred in strikes in England, who had come on at once to Taftville and sought to direct the campaign there.”

The speakers, the Bulletin reported, urged the strikers to demand adoption of a 10-hour work day, more frequent payment of wages, and abolition of the truck system, the English name for the practice whereby wages were paid in the form of goods from the company store or chits redeemable only at the store. The workers complained their accounts were “settled for, not by, them,” according to newspaper reports. Their pay was credited to their accounts at the store, from which their rent and the food they purchased were deducted. They cited frequent errors in the tabulations at the store and the impossibility of getting such errors corrected.

Sources that reported on the strike months later, including the 1875 annual report of Connecticut’s Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), which devoted four pages to the Taftville strike, confirmed that the strikers’ principal complaints were the low wages paid for long hours of labor and the compulsory store system. Weavers in New Bedford, workers said, were paid 16 percent more than those at Ponemah. The BLS reported one worker’s claim that he had “drawn but 4 dollars from February to April, although he and his daughter made $15 a week,” and that in February two pay envelopes were empty. Another worker said he received only 71 cents for three months’ work.In addition, the report said, the first month and three days’ pay was held back by the company, perhaps against the possibility of outstanding debts at the store if the worker left the mill’s employ. Nor would the company advance any money between paydays.

Accounts like these left the mill workers believing that, the BLS report noted, “…the company were (sic) determined to have all their earnings, whether a large or small bill was incurred at the store.” The BLS report concluded, “The whole system of management at Taftville is calculated to make the [workers]completely dependent upon their employers. It treats them as if they were children not to be trusted with their earnings, or else as rogues who would, if permitted to, defraud all with whom they had dealings.”

After a couple of weeks it began to look as if the strike would go on for an extended time, and some workers returned to the mill. Nolan recalled that one morning “…quite a number of houses were liberally covered with a coat of bluing.” The strikers who had returned to work had been dubbed “mobsticks” and their houses covered in the blue liquid added to textiles to optically whiten them. Despite the company’s promise of a reward, the guilty parties were never identified.

The mill owners took a hard line with the strikers. Those who didn’t return to work were evicted from their company-owned homes. An estimated 100 families left Taftville for New Bedford, Fall River, or one of the other nearby textile centers. But the Ponemah Mill owners had a long history of intertwined business relationships with other New England mill owners, making it unlikely that a blacklisted employee would readily find work at another textile mill.

The Ponemah strike was entering its third month before the Norwich Bulletin made any mention of it, although the strike did not go unreported in other cities, including Fall River and Boston. The Bulletin’s June 10, 1875 article proclaimed the strike over yet acknowledged that a few strikers remained off the job. The article did not mention any of the workers’ grievances other than wages, concluding, “We cannot but help regarding it as unfortunate, that the advance [increase]of wages, frankly conceded, was not accepted in the spirit of conciliation and good will in which it was offered… .”

The BLS report quoted the mill superintendent as saying that the company intended to pay the weavers $13 a week, but they struck before the offer was made. Once the workers went out on strike, the company did not “make any effort to induce the strikers to return to work.” Although the general tone of its report appeared sympathetic to the striking workers, the BLS concluded that “there is little or no call for legislative intervention at this time.” Further, it determined “…that the company is unable, from the diminution or decline in prices with that which they formerly received, to comply with the wishes of the [workers].”

By the end of the summer of 1875, new workers had replaced the strikers and the mill was operating at the planned capacity, run by returned strikers and the new hires. The Norwich city directories for the years after the strike (Stedman’s Directory of the City and Town of Norwich, Price & Lee Co., 1875, 1876, 1877) indicate that a substantial number of English, Scottish, and Irish weavers and spinners had left Taftville. Some apparently returned, as enumerated in the 1880 census, but the majority had been replaced by a new immigrant group—French Canadians.

Long-time Taftville resident Rene Dugas Sr. was the youngest of 14 children born to French-Canadian parents who came to Taftville to work in the mill during this period. In his book The French Canadians in New England 1871 – 1930 (privately published, 1995), Dugas recounted the history of Taftville as experienced by his family and others like them.

His parents, Prime and Hosanna Dugas, arrived in 1882. They experience firsthand the clash of cultures between the newly arrived French-Canadians and the Irish. Prime Dugas described what he called “Saturday night entertainment” as he and fellow Frenchmen traded ethnic taunts with the Irishmen until the scene erupted into a brawl. The tensions lasted less than a generation, said Rene Dugas, who claimed many Irish residents of Taftville as good friends throughout his life.

His parents, Prime and Hosanna Dugas, arrived in 1882. They experience firsthand the clash of cultures between the newly arrived French-Canadians and the Irish. Prime Dugas described what he called “Saturday night entertainment” as he and fellow Frenchmen traded ethnic taunts with the Irishmen until the scene erupted into a brawl. The tensions lasted less than a generation, said Rene Dugas, who claimed many Irish residents of Taftville as good friends throughout his life.

As the nation’s economy improved later in the 1870s and 1880s, the mill resumed full production, and more French-Canadians settled in Taftville. In Quebec, most of them had been living with large families in small farmhouses or log cabins in hardscrabble conditions. A four- to seven-room house that was solidly built and warm and a job that provided a regular wage seemed very attractive. Even if the work hours were long and the pay low, it was an improvement in their circumstances. “When compared with today’s standards one would consider these conditions harsh, but at the turn of the century, [today’s standards] were not present. Ponemah was not worse, and in some cases it was better, than many textile centers of that era,” Rene Dugas wrote. “One must consider that because of the large number of textile mills in New England, every mill made an effort to retain its skilled workers, and living and working conditions … were maintained with that aim in view.”

The 1880 census makes it clear that French-Canadians had become the dominant ethnic group in Taftville. Page after page carries the names of residents born in Canada, with only occasional mention of a U.S.-born child of French-Canadian parents. In most cases, those children, and their children, would go to work at Ponemah. French culture and customs came to dominate life in the village until well into the 20th century, when Ponemah Mill finally closed.

Tricia Staley is a retired educator and the author of Norwich in the Gilded Age: The Rose City’s Millionaire’s Triangle and Norwich and the Civil War.

Read more!

“French Canadians Colonize Connecticut,” Fall 2012

Fall 2013: Our New Connections