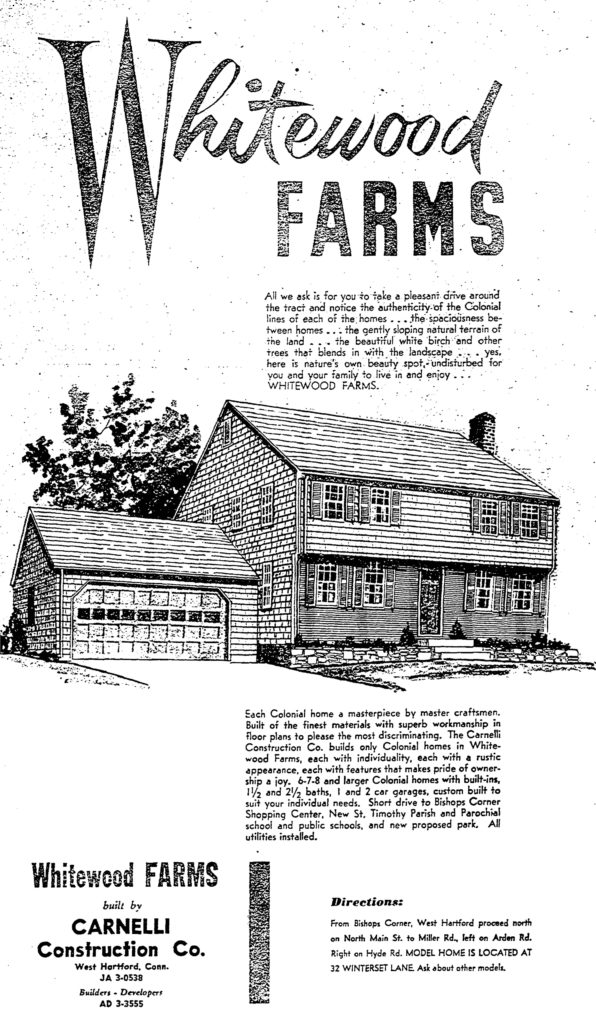

Ads run in 1960 for Carnelli Construction’s Whitewood Farms development in West Hartford point out its proximity to the new St. Timothy’s parish and parochial elementary school built in 1959.

By Tracey Wilson

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Summer 2019

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

We like to think we have the freedom to live where we want. Economics and practicalities guide our decisions, including whether to live in a city, suburb, or rural town, on Main Street or a dead-end road, to own or rent. Historically, though, for Jews and African Americans in towns like West Hartford, discrimination also played a role in these decisions. Discrimination in housing created segregation of whites from blacks, Protestants from Catholics, and both from Jews. Historians document how zoning, redlining, federal mortgages, restrictive covenants, and steering by real estate agents explain segregation. (See “the Federal Government and Redlining in Connecticut” in this issue.)

In the 1930 census West Hartford’s non-white population totaled 129 people (0.5 percentof the total population). Of these, only 30 lived in a household headed by a non-white; that is, 90 lived as servants in white households, according to Jack Dougherty’s online book On The Line: How Schooling, Housing, and Civil Rights Shaped Hartford and its Suburbs.

Home of Howard and Grace Penrose where Gertrude Blanks lived with her mother in the maid’s quarters in the 1920s – 1930s, 2019. photo: Connecticut Explored

Gertrude Blanks, who was African American, remembered moving into a West Hartford home on Steele Road in 1929 with her mother, who was a live-in maid. She shared the story of how her mother, Pearl Boyer, was hired by Howard and Grace Penrose, part of the family that owned the William R. Penrose and Co. Insurance Agency. Gertrude’s mother instructed her nine-year-old daughter to use the back door and not to enter the living room, dining room, or bedrooms, according to a 2004 interview quoted in a January 25, 2019 Hartford Courant article.

Builders who developed farmland in the suburbs played an important role in segregation. Between 1950 and 1970 West Hartford’s population grew by more than 25,000 to about 68,000. Developers built thousands of homes, some with explicit restrictive covenants written into the mortgage. R. G. Bent and Company, for example, developed a neighborhood on Ledgewood Road in the late 1930s, selling it to New York-based High Ledge Homes in 1940. A Ledgewood Homes restrictive covenant from May 26, 1941 read:

No persons of any race other than the white race shall use or occupy any building or any lot, except that this covenant shall not prevent occupancy by domestic servants of a different race domiciled with an owner or tenant.

Historians argue about whether Jews were considered part of the “white race” in these restrictive covenants. A study of West Hartford city directories during the 1940s shows that people with Jewish surnames did not live on the five streets with such restrictive covenants. In 1948 the U.S. Supreme Court unanimously overturned the use of restrictive covenants in Shelley v. Kraemer, ruling that restrictive housing covenants were unconstitutional. The ruling cited the 14th Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause.

Yet exclusionary practices continued. Jews moving to West Hartford in the 1950s and 1960s learned that they couldn’t live on Sunny Reach Drive, near the Hartford Golf Club on Westwood Road, or on Colony Road. West Hill Drive, Hunter Drive; the Sunset Farms subdivision and Wood Pond were off limits, too. Neighborhood associations made sure that houses never went on the market but were passed along by word of mouth to family members or those who were considered “appropriate” to live in the neighborhood. According to West Hartford’s Henry Zachs, if a Jewish family wanted to buy a house along Farmington Avenue and had $30,000 to put down, their real estate agent would advise that if the family were to offer it, the house would just be taken off the market.

Brothers Victor and Raymond Carnelli’s construction company developed hundreds of West Hartford houses between 1945 and 1970. Carnelli Construction Company built on Longlane and Hartwell roads and on Winterset Lane in the north and west sections of town. It also built on Cherryfield Drive and Foxridge Road in the southwest corner. A Hartford Courant ad for a Carnelli home on Richmond Lane, near what is now Eisenhower Park, unabashedly named the development Whitewood Farms. The ad is clearly aimed at Catholic home buyers who would be attracted to the Catholic church and school built nearby in 1959.

Jews in town referred to this area as “Vatican Village,” according to West Hartford lawyer Coleman Levy. He commented at one of my recent book talks that “Jews could not buy a Carnelli home.” In many ways, Carnelli followed the spirit of the times. William Levitt, famous for his developments that became known as Levittowns, refused to sell to blacks, even after the 1948 U.S. Supreme Court case, writes Richard Rothstein in The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How our Government Segregated America (Liveright, 2017).

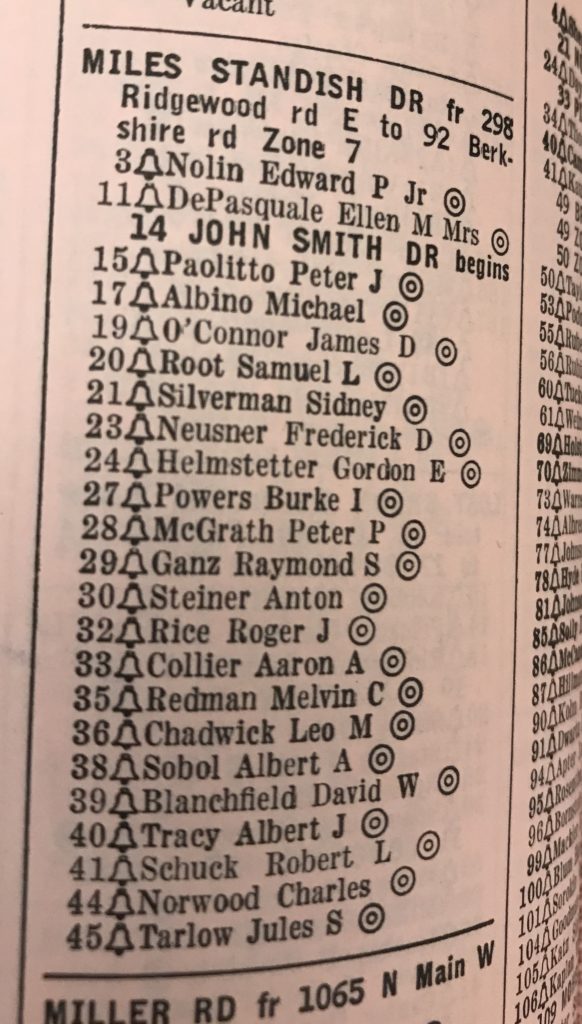

But Carnelli was not the only developer in town. Irving Stich, who was Jewish, also built hundreds of houses in West Hartford. Just two streets south of Carnelli-built homes on Foxridge Road and Sunrise Hill Drive, Stich built houses on John Smith Drive and Miles Standish Drive and sold them to Jews. He developed houses on Sequin Drive near Colony Road and sold them to Jews as well.

Webster Hill Homes, offered by developer Irving Stich without restrictive covenants, abutted the Ledgewood Homes development which had restrictive covenants, West Hartford, 1949.

Sequin and Colony roads, which intersect, illustrate this segregation. The 1958 city directory lists a majority of Jewish surnames among the people who lived on Sequin Road. By contrast, Shari Cantor, West Hartford’s current mayor and a resident on Colony Road since 2009, and others from the neighborhood say that Jews were excluded from buying on that street for many decades after the ample Tudor homes were built in 1929 and 1930. A look at the names from the city directory in 1958 supportsthis assertion.

In 1954 Stich, who owned Ogden Homes, sold 23 Miles Standish Drive to Frederick and Millicent Neusner. Frederick’s father, a Russian immigrant, appears in the 1940 census as a salesman for the Jewish Ledgerliving on Asylum Avenue in West Hartford with his wife and children. Frederick was 15. He went to Hall High School and then Trinity College. Fourteen years later, Frederick and his wife bought the house on Miles Standish Drive.

Price & Lee City Directory, 1958, showing those who lived on Miles Standish Road, developed by Irving Stich. photo: Tracey Wilson

When in 1965 John and Deanie Sullivan Davison wanted to buy a house at 21 Miles Standish Drive, their real estate agent asked them if they were sure they wanted to move into this neighborhood. John related in an interview with me that the agent asked them, “Would they feel comfortable living there?” In addition to the Neusners at number 23, Raymond and Sally Ganz lived at number 29, and Jules and Rosalind Tarlow lived at number 45. All were Jewish families, and when the real estate agent saw that Deanie’s middle name was Sullivan, he worried. The Davisons moved in to this religiously integrated south end neighborhood.

While Christians and Jews lived side by side in some neighborhoods in town, by the 1950s it was a noticeable event to have a black family move to town. Between 1959 and 1973, 265 African American people settled in West Hartford, a town of 70,000 people.

Olivia and Clarence Shelton and their two children moved to 178 North Main Street in 1959. In a 1997 interview archived at the Noah Webster House, Olivia recalled that their next-door neighbor offered them $5,000 not to move in. Soon after, she said, she found a note in her mailbox that read: “Get out of here, you black bastards, while you still can.”

The home of Olivia and Clarence Shelton today, North Main Street, West Hartford. photo: Connecticut Explored

But the Sheltons stayed. They lived in their five-bedroom Tudor for 35 years. Olivia, a former president of the Hartford Chapter of the National Council of Negro Women and the first president of the Hartford Chapter of Delta Sigma Theta Sorority, said her positive experiences outweighed the prejudice she says she experienced. To her, “that note did not represent the community.”

Many in the community supported integration.The Hartford Courant reported in 1966 that Pastor John P. Webster of the First Church of Christ Congregational, where the Sheltons were congregants, said “his church had sponsored 20 Negro families for the past three years” to move into West Hartford through a program with the Connecticut Council of Churches. A West Hartford Interfaith Housing Committee also formed. Its mission was to “aid (financially qualified) minority groups in West Hartford” through local churches, such as the Universalist Church on Fern Street.

In 1973 Shelton said to a West Hartford News reporter, “I don’t like to pretend to put forth that all is well—I’m sure that you’ll run into that, interviewing other black families.” Yet 24 years later, at age 87, Olivia recalled that her overall experience in West Hartford was “very good and wholesome.” She liked living on North Main Street, saying “Most of the people there are Jewish and they were nice to us.” People like Georgette Koopman, who  lived in the Shelton’s neighborhood and welcomed their sons into the Boy Scouts at Bugbee School, embraced the idea of a multi-racial community.

lived in the Shelton’s neighborhood and welcomed their sons into the Boy Scouts at Bugbee School, embraced the idea of a multi-racial community.

Restrictive covenants are a thing of the past, but the issue of racial segregation in neighborhoods continues. In 2016 West Hartford’s 11 neighborhood elementary schools reflected that 42 percent of the school district was made up of students of color. And yet at Bugbee School, not far from the town’s border with Avon, just 14 percent of students were of color, while at Charter Oak School, near the Hartford city line, 81percent of the students were people of color. These demographics reflect the the thorny issue of racial segregation that persists by practice and not by law.

Tracey Wilson is West Hartford’s town historian. In 2018 The Noah Webster House published her book Life in West Hartford. She last wrote “From Steno Pool to Factory Floor,” Winter 2013-2014.

Explore!

Listen to Grating the Nutmeg, episode 43, “The Challenge of Fair Housing in Connecticut’s Suburbs,” featuring Dr. Jack Dougherty and Dr. Tracey Wilson. Ctexplored.org/Listen

“The Federal Government and Redlining in Connecticut,” Summer 2019